SCHOOL of LAW

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mayor's Conference Brochure 2012

Miami-Dade County, Florida International University and The World Bank Invite you to the: XVIII Inter-American Conference of Mayors and Local Authorities + Mayors Forum on Climate Change™ “A New Local Agenda: Democracy, Economic Development, and Environmental Sustainability” June 18- 21, 2012 Hilton Miami Downtown Hotel Miami, Florida – USA www.ipmcs.fiu.edu In cooperation with: THE GOVERNMENT OF MIAMI-DADE COUNTY AND FLORIDA INTERNATIONAL UNIVERSITY INVITE YOU TO PARTICIPATE IN THE XVIII INTER-AMERICAN CONFERENCE OF MAYORS AND LOCAL AUTHORITIES WHICH WILL FOCUS UPON “A NEW LOCAL AGENDA: DEMOCRACY, ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT AND ENVIRONMENTAL SUSTAINABILITY.” The Conference provides efficient without solid and ABOUT THE CONFERENCE an excellent forum for transparent intergovernmental Title: “A New Local representatives of local, relations. Efficient and Agenda: Democracy, regional and national transparent local governments Economic Development and governments, NGOs, various today, more than ever, must Environmental Sustainability,” international and multilateral contribute to building more the Eighteenth Inter-American organizations and all of those equal and just societies. Conference of Mayors and interested in local government Local Authorities. issues to share experiences; Participants: The Conference is When: June 18 - 21, 2012 at the information and best practices; annually attended by mayors, Hilton Miami Downtown Hotel discuss public policy and governors, legislators and Miami, FL. (Opening Reception common goals which can other elected representatives - evening of June 18, 2012 at aid in the development of of, as well as senior executive the hotel). local government and help to officials from, the local, Sponsorship: Miami-Dade promote decentralization in regional and national County Government, the World the region. -

Design Considerations for Retractable-Roof Stadia

Design Considerations for Retractable-roof Stadia by Andrew H. Frazer S.B. Civil Engineering Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 2004 Submitted to the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of AASSACHUSETTS INSTiTUTE MASTER OF ENGINEERING IN OF TECHNOLOGY CIVIL AND ENVIRONMENTAL ENGINEERING MAY 3 12005 AT THE LIBRARIES MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY June 2005 © 2005 Massachusetts Institute of Technology All rights reserved Signature of Author:.................. ............... .......... Department of Civil Environmental Engineering May 20, 2005 C ertified by:................... ................................................ Jerome J. Connor Professor, Dep tnt of CZvil and Environment Engineering Thesis Supervisor Accepted by:................................................... Andrew J. Whittle Chairman, Departmental Committee on Graduate Studies BARKER Design Considerations for Retractable-roof Stadia by Andrew H. Frazer Submitted to the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering on May 20, 2005 in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Engineering in Civil and Environmental Engineering ABSTRACT As existing open-air or fully enclosed stadia are reaching their life expectancies, cities are choosing to replace them with structures with moving roofs. This kind of facility provides protection from weather for spectators, a natural grass playing surface for players, and new sources of revenue for owners. The first retractable-roof stadium in North America, the Rogers Centre, has hosted numerous successful events but cost the city of Toronto over CA$500 million. Today, there are five retractable-roof stadia in use in America. Each has very different structural features designed to accommodate the conditions under which they are placed, and their individual costs reflect the sophistication of these features. -

Miami-Dade County Opioid Addiction Task Force Implementation Report

Opioid Addiction Task Force Implementation Report BACKGROUND 2016 Miami-Dade Opioid Addiction Task Force Formation In response to the illicit and prescription opioid addiction and overdose epidemic in Miami-Dade County, Mayor Carlos A. Gimenez, in partnership with the State Attorney Katherine Fernandez-Rundle, the Department of Children and Families, the Florida Department of Health, and Miami-Dade County's Board of County Commissioners Chairman Esteban L. Bovo, Jr. founded the Miami-Dade County Opioid Addiction Task Force. Members of the Task Force consist of several subject-matter experts and stakeholders representing agencies, departments, and offices working to end the opioid epidemic. Based on a review of evidence-based and evidence-informed practices, the Task Force provided recommendations to reduce opioid overdoses, prevent opioid misuse and addiction, increase the number of persons seeking treatment, and support persons recovering from addiction in our communities. The Task Force also examined healthcare solutions, the role of the justice system in opioid prevention, and raising awareness and improving knowledge of misuse. IMPLEMENTATION The Opioid Addiction Task Force recognizes the serious public health problems associated with the opioid epidemic occurring in Miami-Dade County. Task Force Members created an action plan with 26 recommendations that invoke sustained population-wide health improvements. The participating agencies understand that combining community efforts can achieve a lasting social change and are committed to implementing these recommendations to the extent that resources and legal authority allow. The members of the Task Force strongly encourage all other organizations and individuals to do the same. Entities, charged with implementing specific recommendations, report on their progress quarterly to staff support. -

LIVING WAGE ORDINANCE Sec. 2-8.9

LIVING WAGE ORDINANCE Sec. 2-8.9. - Living Wage Ordinance for County service contracts and County employees. Definitions. (A) Applicable department means the County department using the service contract. (B) County means the government of Miami-Dade County or the Public Health Trust. (C) Covered employee means anyone employed by any Service Contractor, as further defined in this Chapter either full or part time, as an employee with or without benefits that is involved in providing service pursuant to the Service Contractor's contract with the County. (D) Covered employer means any and all service contractors and subcontractors of service contractors. (E) Service contractor is any individual, business entity, corporation (whether for profit or not for profit), partnership, limited liability company, joint venture, or similar business that is conducting business in Miami-Dade County or any immediately adjoining county and meets the following criteria: (1) The service contractor is paid in whole or part from one (1) or more of the County's general fund, capital project funds, special revenue funds, or any other funds either directly or indirectly, whether by competitive bid process, informal bids, requests for proposals, some form of solicitation, negotiation, or agreement, or any other decision to enter into a contract; (2) The service contractor is engaged in the business of, or part of, a contract to provide, a subcontractor to provide, or similarly situated to provide, covered services, either directly or indirectly for the benefit of the County; or (3) The service contractor is a General Aeronautical Service Permittee (GASP) or otherwise provides any of the Covered Services as defined herein at any Miami- Dade County Aviation Department facility including Miami International Airport pursuant to a permit, lease agreement or otherwise. -

Miami-Dade County “Getting to Zero” HIV/AIDS Report

1 Miami-Dade County “Getting to Zero” HIV/AIDS Report Make HIV History! Know the Facts □ Get Tested □ Get Treated Implementation Report 2017-2018 4/24/2018 1 2 4/24/2018 2 3 Progress on the “Getting to Zero”: Goals 2015 2016 2020 (Baseline) Goal Goal 1: Know the Facts: 90% of all Miami-Dade County Data 86% 90% residents living with HIV will know their status. Pending Goal 2: Get Tested: Reduce the number of new diagnosis by at least 25%. 1,344 1,270 1,008 Goal 3: Get Treated: 90% of Miami-Dade County residents living with HIV who are in treatment reach viral 55.7% 57% 90% load suppression Goal 1: Know the Facts: 90% of all Miami-Dade County residents living with HIV will know their status. The first step of HIV treatment is timely diagnosis. The recommendations call for increased and targeted HIV testing, as well as expansion of rapid access treatment sites. In 2015, Florida Department of Health (FDOH) estimated that 86% of HIV-positive individuals were aware of their HIV status. The 2016 epidemiological report is pending an updated estimate of the percentage of HIV-positive individuals who know their status. Goal 2: Get Tested: Reduce the number of new diagnosis by at least 25%. There is a goal to achieve a 25% reduction in new HIV cases by 2020. The plan details recommendations that will enhance prevention efforts through increased access to PrEP and post- exposure prophylaxis (PEP), improve youth education, and identify root causes of stigma. In 2015, there were 1,344 new cases of HIV diagnosis. -

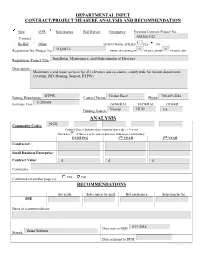

Analysis and Recommendation

DEPARTMENTAL INPUT CONTRACT/PROJECT MEASURE ANALYSIS AND RECOMMENDATION New OTR Sole Source Bid Waiver Emergency Previous Contract/Project No. SS1246-3/22 Contract Re-Bid Other LIVING WAGE APPLIES: YES NO ITQ687-1 5 0 Requisition No./Project No.: TERM OF CONTRACT YEAR(S) WITH YEAR(S) OTR Requisition /Project Title: Installation, Maintenance, and Modernization of Elevators Description: Maintenance and repair services for 431 elevators and escalators, county wide for various departments (Aviation, ISD, Housing, Seaport, DTPW) Issuing Department: DTPW Contact Person: Froilan Baez Phone: 786-469-5244 Estimate Cost: 11,298,595 GENERAL FEDERAL OTHER Funding Source: Various HUD n/a ANALYSIS Commodity Codes: 29570 Contract/Project History of previous purchases three (3) years Check here if this is a new contract/purchase with no previous history. EXISTING 2ND YEAR 3RD YEAR Contractor: Small Business Enterprise: Contract Value: $ $ $ Comments: YES Continued on another page (s): NO RECOMMENDATIONS Set-aside Sub-contractor goal Bid preference Selection factor SBE Basis of recommendation: Date sent to SBD: 03/1/2018 Signed: Brian Webster Date returned to DPM: Revised April 2005 INVITATION TO QUOTE (ITQ) NO: ITQ687- 1 ITQ CLOSE DATE/TIME: ITQ TITLE: Installation, Maintenance, and Modernization of Elevators CONTACT PERSON: Brian Webster CONTACT PHONE/ EMAIL: 305-375-2676 ISSUING DEPARTMENT: Miami-Dade County Internal Services Department Procurement Management Services SECTION 1 – GENERAL TERMS AND CONDITIONS GENERAL TERMS AND CONDITIONS: All general terms and conditions of Miami-Dade County Procurement Contracts are posted online. Bidders/Proposers that receive an award through Miami-Dade County's competitive procurement process must anticipate the inclusion of these requirements in the resultant Contract. -

Chapter 189, F.S

THE LOCAL GOVERNMENT FORMATION MANUAL 2017-2018 Government Accountability Committee Representative Matt Caldwell, Chair Local, Federal & Veterans Affairs Subcommittee Representative Scott Plakon, Chair 209 House Office Building 402 South Monroe Street Tallahassee, FL 32399-1300 (850) 717-4890 http://www.myfloridahouse.gov PREFACE TO 2017 – 2018 EDITION A number of revisions were made to this edition of the Local Government Formation Manual. The content of each chapter was reviewed and conformed to current law. Supporting source materials, including publication citations and internet web addresses, were reviewed to verify their continuing reliability. References to source materials that are no longer readily available were removed. In chapters 2014-22 and 2016-22, Laws of Florida, the Legislature revised, restructured, and reorganized the Uniform Special District Accountability Act, chapter 189, F.S. Accordingly, Chapter 5 of this manual was revised to incorporate these changes. A table tracing the former (pre-2014) sections of chapter 189, F.S., to the renumbered sections created by the 2014 and 2016 changes and to the sections of the law where those changes are made, is included as Appendix J. To improve the clarity and readability of the text, a number of lists and charts previously incorporated into the text were removed and reconstituted as new appendices. Some existing appendices were renumbered, but former appendices providing various statistics on special districts are no longer included as the information provided is more readily available (and more current) at the website of the Florida Department of Economic Opportunity, Division of Community Development, Special District Accountability Program, at http://www.floridajobs.org/community-planning-and-development/special- districts/special-district-accountability-program. -

Meeting Minutes

City of Miami City Hall 3500 Pan American Drive Miami, FL 33133 www.miamigov.com Meeting Minutes Thursday, April 12, 2012 9:00 AM REGULAR City Hall Commission Chambers City Commission Tomas Regalado, Mayor Francis Suarez, Chairman Marc David Sarnoff, Vice-Chairman Wifredo (Willy) Gort, Commissioner District One Frank Carollo, Commissioner District Three Michelle Spence-Jones, Commissioner District Five Johnny Martinez, City Manager Julie O. Bru, City Attorney Priscilla A. Thompson, City Clerk City Commission Meeting Minutes April 12, 2012 CONTENTS PR - PRESENTATIONS AND PROCLAMATIONS AM - APPROVING MINUTES MV - MAYORAL VETOES CA - CONSENT AGENDA PH - PUBLIC HEARINGS SR - SECOND READING ORDINANCES FR - FIRST READING ORDINANCES RE - RESOLUTIONS BC - BOARDS AND COMMITTEES DI - DISCUSSION ITEMS MAYOR AND COMMISSIONERS' ITEMS M - MAYOR'S ITEMS D1 - DISTRICT 1 ITEMS D2 - DISTRICT 2 ITEMS D3 - DISTRICT 3 ITEMS D4 - DISTRICT 4 ITEMS D5 - DISTRICT 5 ITEMS City of Miami Page 2 Printed on 5/7/2012 City Commission Meeting Minutes April 12, 2012 9:00 A.M. INVOCATION AND PLEDGE OF ALLEGIANCE Present: Commissioner Gort, Vice Chair Sarnoff, Commissioner Carollo, Chair Suarez and Commissioner Spence-Jones On the 12th day of April 2012, the City Commission of the City of Miami, Florida, met at its regular meeting place in City Hall, 3500 Pan American Drive, Miami, Florida, in regular session. The Commission Meeting was called to order by Chair Suarez at 9:00 a.m., recessed at 9:01 a.m, reconvened at 9:05 p.m., recessed at 11:23 a.m, reconvened at 2:00 p.m, recessed at 6:11 p.m, reconvened at 6:25 p.m.and adjourned at 7:54 p.m. -

Miami-Dade County Board of County Commissioners Office of the Commission Auditor Board of County Commissioners Meeting

Miami-Dade County Board of County Commissioners Office of the Commission Auditor Board of County Commissioners Meeting June 7, 2016 9:30 A.M. Commission Chamber Research Division Charles Anderson, CPA Commission Auditor 111 NW First Street, Suite 1030 Miami, Florida 33128 305-375-4354 Board of County Commissioners June 7, 2016 Meeting Research Notes Item No. Research Notes 4A ORDINANCE PERTAINING TO SMALL BUSINESS ENTERPRISE PROGRAMS; AMENDING SECTION 2‐8.1.1.1.2 OF THE CODE OF MIAMI‐DADE 161115 COUNTY, FLORIDA TO PROVIDE FOR INCREASED PENALTIES TO BE PAID BY CONTRACTORS AND SUB‐CONTRACTORS UPON FAILURE TO MEET GOAL REQUIREMENTS; AND PROVIDING SEVERABILITY, INCLUSION IN THE CODE, AND AN EFFECTIVE DATE Notes The proposed ordinance amends Section 2‐8.1.1.1.2 of the Miami‐Dade County Code relating to the Small Business Enterprise Goods Program to provide for increased penalties to be paid by contractors and sub‐contractors upon failure to meet goal requirements. Specifically, contractors and sub‐contractors may be sanctioned in the following ways: Penalties payable to the County in an amount equal to 20% of the amount of the underpayment of wage and/or benefits for the first instance of underpayment; 40% for the second instance; 60% of the amount of underpayment for the third and successive instances; an A fourth violation will constitute a default of the contract where the underpayment occurred and may be cause for suspension or termination in accordance with the debarment procedures of the County. 4B ORDINANCE PERTAINING TO SMALL BUSINESS -

Regional Aspects of Miami Crime Fiction Heidi Lee Alvarez Florida International University

Florida International University FIU Digital Commons FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations University Graduate School 2-19-1999 Regional aspects of Miami crime fiction Heidi Lee Alvarez Florida International University DOI: 10.25148/etd.FI14031604 Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Alvarez, Heidi Lee, "Regional aspects of Miami crime fiction" (1999). FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 1263. https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd/1263 This work is brought to you for free and open access by the University Graduate School at FIU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of FIU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FLORIDA INTERNATIONAL UNIVERSITY Miami, Florida REGIONAL ASPECTS OF MIAMI CRIME FICTION A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in ENGLISH by Heidi Lee Alvarez 1999 To: Dean Arthur W. Herriott College of Arts and Sciences This thesis, written by Heidi Lee Alvarez, and entitled Regional Aspects of Miami Crime Fiction, having been approved in respect to style and intellectual content, is referred to you for judgment. We have read this thesis and recommend that it be approved. Mary ne Ek's Gregory Bowe Kenneth Johnson. Major Professor Date of Defense: March 19, 1999 The thesis of Heidi Lee Alvarez is approved. Dean Arthur W. Herriott College pf Arts and Spjences Dean Richard L. Camp ell Division of Graduate Studies Florida International University, 1999 ii © Copyright 1999 by Heidi Lee Alvarez All rights reserved. -

Invitation to Bid

BID NO.: 5745-2/14 OPENING: 2:00 P.M. Wednesday September 17, 2008 MIAMI-DADE COUNTY, FLORIDA INVITATION T O B I D TITLE: Parts and Repair Services for Transit Buses and other Support Equipment, Pre- Qualified Pool of Vendors THE FOLLOWING ARE REQUIREMENTS OF THIS BID, AS NOTED BELOW: BID DEPOSIT AND PERFORMANCE BOND: ................................N/A CATALOGUE AND LISTS: ................................ ................................See Section 2, 2.26 CERTIFICATE OF COMPETENCY: ................................ ..................See Section 2, 2.14 EQUIPMENT LIST: ................................................................ ...............N/A EXPEDITED PURCHASING PROGRAM (EPP) N/A INDEMNIFICATION/INSURANCE: ................................ ...................See Section 2, 2.11 LIVING WAGE: ................................................................ ....................See Section 2, 2.33 PRE-BID CONFERENCE/WALK-THRU: ................................ N/A SMALL BUSINESS ENTERPRISE MEASURE: ................................See Section 2, 2.2 SAMPLES/INFORMATION SHEETS: ................................ ...............N/A SECTION 3 – MDHA: ................................................................ ............N/A SITE VISIT/AFFIDAVIT: ................................ ................................N/A USER ACCESS PROGRAM: ................................ ................................See Section 2, 2.21 WRITTEN WARRANTY: ................................ ................................See Section 2, 2.19 FOR INFORMATION -

Little Havana Miami, Florida

Clemson University TigerPrints Master of Architecture Terminal Projects Non-thesis final projects 5-1979 A Community Center: Little aH vana Miami, Florida Roberto Luis Sotolongo Clemson University Follow this and additional works at: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/arch_tp Part of the Architecture Commons Recommended Citation Sotolongo, Roberto Luis, "A Community Center: Little aH vana Miami, Florida" (1979). Master of Architecture Terminal Projects. 159. https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/arch_tp/159 This Terminal Project is brought to you for free and open access by the Non-thesis final projects at TigerPrints. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master of Architecture Terminal Projects by an authorized administrator of TigerPrints. For more information, please contact [email protected]. • • A CO~fMUNITY CENTER : LirfTLE HAVANA 1-1IAMI , FI,ORIDA A t e rmina l project st1bmi t ted t o the f ac ul ty o E the Co llege of Architecture Clemson University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARCHITECTURE Committee Chairman ead , Dept . of Architectural Studies De.1n, College of Architecture ,' / 1' - / / Reiber l o Luis Soto long(1 May J 979 ACKNOWLEDGE}fENTS I should like to tl1ar1k my• parents f:or tl1eir support in every sense in my educational enlightenment . I am gr at e [ u l to t l1 e fa cu 1 t y a t t 11 e Co 11 e g e o £ Arch i t e c tu re , particuJ arJ y Dean Harle11 ~lcClure Professor Frederick Roth, Dr . Johannes Holschneider and Professor Robert Eflin, for their furthering of my social and Arcl1itec tural knowledge .