Song Fest Features Freedy Johnston Past Rolling Stone Magazine's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nightshiftmag.Co.Uk @Nightshiftmag Nightshiftmag Nightshiftmag.Co.Uk Free Every Month NIGHTSHIFT Issue 285 April Oxford’S Music Magazine 2019

[email protected] @NightshiftMag NightshiftMag nightshiftmag.co.uk Free every month NIGHTSHIFT Issue 285 April Oxford’s Music Magazine 2019 “The mask probably is a defence mechanism. Focussing on this character of Tiger Mendoza rather than photo: Helen Messenger me as a person removes the notion of personality or race or even gender.” tiger mendoza Oxford’s collaboration king talks masks, movies & remixes Also in this issue: THE CELLAR - RIP WHEATSHEAF in peril? Introducing MEANS OF PRODUCTION FESTIVAL NEWS - the latest on Truck, Cornbury, Supernormal, Tandem & more plus all your Oxford music news, previews, reviews and five pages of gigs for April NIGHTSHIFT: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU. Phone: 01865 372255 NEWS Nightshift: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU Phone: 01865 372255 email: [email protected] Online: nightshiftmag.co.uk THE CELLAR CLOSED ITS agreed, there were no guarantees doors for the last time on the 11th on the time frame of the building March. work, which required access to the The venue, which has been at the shop above and various structural heart of the Oxford music scene for considerations. Essentially, the 40 years under the ownership of the whole process took far longer than Hopkins family, was forced to shut we were expecting, and we simply after it failed to reach an agreement could not keep operating under these with landlords The St Michael’s and conditions. All Saints “charity”, over a new rent “We are grateful to the landlords for deal. recognising the cultural importance The closure comes at the end of of the venue, and we hope that an 18-month period that saw The we have saved this space from Cellar survive an application for a becoming a store room. -

John Quincy's Core Music Library

DJ John Quincy CORE MUSIC LIBRARY 'N Sync - Bye Bye Bye [Intro Edit] (3:07) 'N Sync - Girlfriend (4:12) 'N Sync - God Must Have Spent A Little More Time On You (3:58) 'N Sync - Gone (4:22) 'N Sync - I Drive Myself Crazy (3:55) 'N Sync - I Want You Back (3:18) 'N Sync - It's Gonna Be Me (3:10) 'N Sync - Pop (2:53) 'N Sync - Tearin' Up My Heart (3:26) 'N Sync - This I Promise You (4:21) 10,000 Maniacs - Because The Night (3:35) 10,000 Maniacs - More Than This (3:52) 100 Proof Aged In Soul - Somebody's Been Sleeping (4:05) 10cc - I'm Not In Love (3:47) 10cc - Things We Do For Love (3:20) 112 - Peaches & Cream (2:52) 12 Gauge - Dunkie Butt (4:54) 12 Stones - Way I Feel (3:44) 1910 Fruitgum Company - 1, 2, 3 Red Light (2:05) 1910 Fruitgum Company - Indian Giver (2:37) 1910 Fruitgum Company - Simon Says (2:12) 2 Pistols - She Got It (3:49) 2 Unlimited - Get Ready For This (3:41) 2 Unlimited - Twilight Zone [Intro Edit] (3:50) 3 Doors Down - Be Like That (3:54) 3 Doors Down - Here Without You (3:48) 3 Doors Down - It's Not My Time (3:42) 3 Doors Down - Kryptonite (3:51) 3 Doors Down - Let Me Go (3:45) 3 Doors Down - When I'm Gone (4:12) 311 - Hey You (3:49) 311 - Love Song (3:24) 38 Special - Back Where You Belong (4:23) 38 Special - Caught Up In You (4:30) 38 Special - Fantasy Girl (3:56) 38 Special - Hold On Loosely (4:29) 38 Special - If I'd Been The One (3:47) 38 Special - Like No Other Night (3:46) 38 Special - Rockin' Into The Night (3:48) 38 Special - Second Chance (4:55) 38 Special - Wild-Eyed Southern Boys (4:10) 3LW - No More (Baby -

Pajisad.Es Free Library PALISADES

lni(§ PaJisad.es Free Library Mot to be taken from this room THE PALISADES NEWSLETTER DECEMBER 2004 NUMBER 187 PALISADES KINDER GAR TNERS +he end nf December is a season filled with festivals •f liaht, when we a need it mast. +his liafit reminds us that the sun will eventually vanquish the cold and darkness nf winter- and our children remind us that jay, curiosity and Growth are the key to everyone's future. CLASS OF 2017 LEFT TO RIGHT: Henry Garrison, Katie Lappin, Rontan Carroll, Dionna Sheer, Shaan Greenberg, Cole Thomas Cappelletti, Kevin Lynch. PHOTOS: GERRY MIRAS A Dark Season That Celebrates Light +he Spirit Is Willing but the Supply Chain is Weak... by Greta Nettleton lions of other workers seated in front of On a damp, grey day their computers are doing all across our in mid-November, metropolitan area in a mind-bending array of 'diverse' jobs and professions. None of us it's not hard to understand the has to go out into the fields in the rain and whack clods of cold black mud with a short- fundamental need handled hoe to dig up turnips for dinner - to celebrate light we eat well, easily, winter and summer. and warmth in December. For better or for worse, petroleum plays the key role in supporting the many comforts utside, the sky seems dark even at provided by our civilization as it is orga• midday and cold rain falls steadily nized right now. (Gas is still as cheap as bot• Othrough the woods. Inside, the tled water — compare the prices next time house is warm, the dog lies sleeping by the you go to a convenience store.) radiator on his little red rug and the radio emits a cheerful parade of Irish fiddle tunes. -

Com ,S Oftate

THE MOST TRUSTED NAME IN RADIO ISSUE 2011 JULY 1, 1994 This Week You could call this issue 'Three Men and a Baby (Format)." And so could we. That's because the A3 format is one year old, and, to observe this Gavin anniver- sary, we spoke with three artists happy to call A3 a radio home. They are Bruce Cockburn (our cover photo), Peter Himmelman (above), and Luka Bloom (below, right). For this celebration, we also called on radio stations and music com- panies for an update on person- nel and summer releases, along with their suggestions for hot - button topics to be discussed at our next A3 Summit in Boulder in August. Also sig- nifying growth: a new, Extended Grid to allow lit- tle A3 to grow gracefully out of its diapers. Happy, happy birthday, baby...In News, George Michael gathers himself-and his attorneys-for a probable appeal in his battle with Sony, while Don Henley appears close to settling Geffen Records' suit against him. President Clinton takes the talk - show route to rout such neme- GAVI A3 ses as Rush Limbaugh; top talker Howard ,s Stern puts his Com OftAte radio show on TV; an awe- It's A3'sFirsiAnniverAary, some auction of Elvis memo- rabilia pulls in and we a King's ransom of S2 million. The Museum of Television & Radio in New York hosts a year -long 3 artists hap tribute to rock and roll radio (and such pioneers as Alan homes, a pI of plo eers who talk Freed, above ) while Music City invades Windy City's Museum of Broadcast Communications for about the foat's4wItaing issues, the summer. -

The Following Issue Is Misnumbered and Dated. It Should Have

The following issue is misnumbered and dated. It should have appeared as Vol. 16, No. 9, Feb. 6, 1995. Sn71 TV/ XKT-. 1i r'~r TnTTLrnroV l-CiT Patirep'nrnrirMllnltv' r raer reuruaivJ u, p On The Inside E~t A F3~rW?~fP~i~iP S ~E~Cm~ · P~ a---~-~·--aa~onrs*;·i 77 !/17 Ile to 777:,-sa~aer wo a. pa~j~g by Robert V. Gilheany station to station because of the attention he paid to because he felt that Mumia was too gifted a speaker and MOVE. The police attacked MOVE in 1978. 15 it was unfair to the prosecution. He also denied him his Support is growing to free Mumia Abu-Jamal, a political MOVE members were convicted of killing one cop, right to the council of his choice, which was MOVE prisoner On death row in Pennsylvania. A defense to save who was actually killed by another cop in a case of leader John Africa, Sabo saddled Mumia with an inex- his life is being fought. Moves to get him a new trial is "friendly fire." In case of police brutality the victim perienced unprepared counsel, who was latter disbarred underway and on Saturday February 11 a rally will be held gets charged with assault. Mumia followed the story and from practicing law. Mumia protested during the trial at PS. 41 116 W. street 11th (at 6th ave) in Manhattan. interviewed MOVE in prison. This lead to a public and was banished from the court room. Mumia spent Who is Mumia Abu-Jamal, he is a black radical advo- threat from then Mayor Frank Rizzo aimed at Mumia most of his trial in a jail cell. -

CB-1995-04-22.Pdf

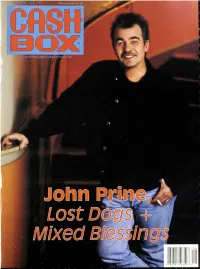

1 0 82791 1 9359 s VOL. LVIII, NO. 32 APRIL 22, 1995 NUMBER ONES STAFF POP SINGLE GEORGE ALBERT President and Publisher I Know KEITH ALBERT Dionne Farris Exec. V.PJGeneral Manager (Columbia) RICH NIECIECKI Managing Editor EDITORIAL R&B SINGLE Los Angeles MICHAEL MARTINEZ This Is How We Do It JOHM GOFF Montell Jordan STEVE BALTIN Cover Story HECTOR RESENDEZ, Latin Edtor (PMP/RA/Island) NashMIle RICHARD McVEY, Edtor John Prine, Lost Dogs + Mixed Blessings New York RAP SINGLE TED WILLIAMS CHART RESEARCH Singer/songwriter John Prine has been plugging away for more than 20 years Dear Mama Los Angeles 2Pac now in relative obscurity to the general public but held in high regard by NICKI RAE RONCO BRIAN PARMELLY (Interscope) artists, critics and discriminating music lovers. His last album The Missing ZIV Years released on his own independent label Oh Boy Records, earned him NashMIle , GAIL FRANCESCHI COUNTRY SINGLE increased notoriety, and his just-released Lost Dogs + Mixed Blessings should MARKETING/ADVERTISING continue that trend. Los Angeles The Heart Is A Lonely Hunter GARY YOUNGER Reba McEntire —see page 5 Nashville TED RANDALL (MCA) New York News NOEL ALBERT Latin Consultant EDDIE RODRIGUEZ POP ALBUM The R.I. A. A. reports that first-quarter tallies of Platinum albums are up more (213) 845-9770 Me Against The World than 50% over the same period last year while multi-Platinum albums have CIRCULATION NINA TREGUB, Manager 2Pac doubled something the Atlantic would certainly attest to, as the — Group PASHA SANTOSO (Interscope) industry leader for all of 1994 is #\ to this point in 1995. -

FREEDY JOHNSTON Peppermint Lavender After Eight Years, He’S Back Thanks to Some Rosalina Coconut Oil Discipline in the Studio Instruction Booklet

JAN/FEB 2010 ISSUE MMUSICMAG.COM SPOTLIGHT Earth Sweet Essential Oils Don’t Miss Performances Due To Illness! Avoid Going To The Doctor. Take Care Of Yourself Naturally. Just $4 ss than the cost o 0 le f one doctors visit. Our Emergency Home Care Kit contains medicinal grade essential oils. Chris Carroll It includes: Tea Tree Eucalyptus Tropical Basil Geranium FREEDY JOHNSTON Peppermint Lavender After eight years, he’s back thanks to some Rosalina Coconut Oil discipline in the studio Instruction booklet FREEDY JOHNSTON DIDN’T MEAN TO The producer also pushed Johnston spend eight years between albums. “I tried toward a recording process featuring a to make it a couple times on my own, and combination of live adrenaline and studio it didn’t work out for various reasons,” says craft. “We did live band tracks with the the singer-songwriter. He discovered the key drums, bass and guitars,” says Johnston. to his new Rain on the City album when he “But Richard said, ‘Freedy, I know you don’t brought in producer Richard McLaurin as his want to do this, but I want you to overdub collaborator. “You learn some lessons and go your vocals, because it’s going to sound down one hallway, fi nd a dead end, and turn more rock.’ So I went with it, and I agree! I around and head down another hallway.” like hearing really good, well-done vocals— Chasing down those possible directions and you don’t always get that with a live Small enough to fit in your led Johnston to cover a lot of territory— vocal.” Also helping the album to sound pocket, but powerful enough literally. -

Song List by Artist

song artist album label dj year-month-order sample of the whistled language silbo Nina 2006-04-10 rich man’s frug (video - movie clip) sweet charity Nayland 2008-03-07 dungeon ballet (video - movie clip) 5,000 fingers of dr. t Nayland 2008-03-08 plainfin midshipman the diversity of animal sounds Nina 2008-10-10 my bathroom the bathrooms are coming Nayland 2010-05-03 the billy bee song Nayland 2013-11-09 bootsie the elf bootsie the elf Nayland 2013-12-10 david bowie, brian eno and tony visconti record 'warszawa' Dan 2015-04-03 "22" with little red, tangle eye, & early in the mornin' hard hair prison songs vol 1: murderous home rounder alison 1998-04-14 phil's baby (found by jaime fillmore) the relay project (audio magazine) Nina 2006-01-02 [unknown title] [unknown artist] cambodian rocks (track 22) parallel world bryan 2000-10-01 hey jude (youtube video) [unknown] Nina 2008-03-09 carry on my wayward son (youtube video) [unknown] Nina 2008-03-10 Sri Vidya Shrine Prayer [unknown] [no album] Nina 2016-07-04 Sasalimpetan [unknown] Seleksi Tembang Cantik Tom B. 2018-11-08 i'm mandy, fly me 10cc changing faces, the best of 10cc and polydor godley & crème Dan 2003-01-04 animal speaks 15.60.76 jimmy bell's still in town Brian 2010-05-02 derelicts of dialect 3rd bass derelicts of dialect sony Brian 2001-08-09 naima (remix) 4hero Dan 2010-11-04 magical dream 808 state tim s. 2013-03-13 punchbag a band of bees sunshine hit me astralwerks derick 2004-01-10 We got it from Here...Thank You 4 We the People... -

Ten Years of Student Support

May find your story 2015 May holidays The Library will be closed on Me- Ten years of student support morial Day weekend: Saturday, May 23, Sunday, May 24 and Monday, “It really helps Derrick with his Board member Ellen Fox, and musi- May 25. homework. He loves the socialization, cian and educator Doreen Gamell. the teens and especially the singing. The Center provides teens FOL Book & My wife and I are so happy that he and adults with an opportunity for uses the library and is able to get the meaningful community service by Author Luncheon books he needs for school. This pro- acting as mentor/tutors each week. There’s still time to reserve your seat gram has our entire family using the Volunteers range from high school at the FOL Book & Author Lun- library.” -Manuel S., parent students to retired educators, a mix cheon on Friday, May 15 at 11 a.m. Congratulations to the Port which provides multiple types of The featured authors will be Jules Washington Education Foundation expertise and points of view to share Feiffer and Mary Gordon, with Su- Support Center on its tenth anniver- with the students. It is a unique learn- san Isaacs returning as moderator. sary! The Center provides after-school ing opportunity for all involved: the See page 2 in this issue for more in- academic support, homework as- teens learn how to mentor and work formation. sistance and arts enrichment to forty with adult volunteers, and the third third graders each year, with one-on- graders get the help they need in a one and small group instruction. -

Network-40-1994-12-0

Issue 241 December 2, 1994 RCA VP Promotion OLD SCHOOL Editorial Spotlight On: WXLK Roanoke NEW YEAR'S Promotions Country Commentary "buddy the follow up to the hit s. rgle cnd M -V buzz bin favorite "uncone the sweate- song' from the self tit ed gold a bum 273,465 urits soldover the counter at soundscal Produced by Ric Ocasek ManAlertent B)) Cavollo/Fct Mcginarella CO- ?9-11Ge4en #241 published by NETWORK 40 INC. 120 N. Victory 81., Burbank, CA 91502 phone (818) 955-4040 fax (818) -9870 e-mail NEPNORINO@AOLCOM AN OUT THIS WEEK MARIAH CAREY "All I Want For Christmas Is You" #1 Most Added #1 PPW (COLUMBIA) MADONNA BOYZ II MEN CANDLEBOX "Cover Me" (MAVERICK/ SIR E/WB) On The Cover: Street Chart / Rhythm Nation 24 Skip Bishop... in a Tom Waits kinda mood. BIG AUDIO Crossover Music Meeting 26 "Looking For A Song" (COLUMBIA) News 4 X Chart / X News 28 GLADYS KNIGHT Page 6 6 "End Of The Road" Country Editorial 32 (MCA) The whole truths, the half-truths and anything but the truth... Of Fish And Trees. POWER RANGERS "TV Theme" Editorial 8 Retail Chart / Bin Burners 32 (ATLANTIC /A.3) Old School. The Top -40 albums; the Top -5 records with the biggest sales increases. HUEY LEWIS AND THE NEWS Network 40 Interview 10 Show Prep 34 "Little Bitty Pretty One" RCA Records VP Promotion Skip Bishop Play It, Say It! / Rimshots (ELEKTRA) Most Requested 36 WILLI ONE BLOOD Conference Call 12 "Whiney. Whiney (What A Network 40 exclusive: four pages of the hottest reaction records "Top 5 of '94." Really Drives Me Crazy)" (RCA) Picture Pages 44 Network 40 Spotlight 16 SOUNDGARDEN "Fell On Black Days" WXLK Roanoke Now Playing 48 (A&M) Spin Cycle 56 3RD NATION Promotions 18 "I Believe" All the pertinent data on every song in Network 40s Top80 PPW chart. -

Freedy Johnston Bio

Freedy Johnston Bio A gifted songwriter whose lyrics paint sometimes witty, often poignant portraits of characters often unaware of how their lives have gone wrong, Freedy Johnston seemingly appeared out of nowhere in the early '90s and quickly established himself as one of the most acclaimed new singer/songwriters of the day. Johnston enrolled at the University of Kansas in Lawrence; and while his academic career didn't last very long, he wasted no time immersing himself in the city's new wave scene. After several years of working in restaurants and writing songs on a four-track recorder in the evening, Johnston pulled up stakes in 1985 and moved to New York City. After several years of making the rounds, his work caught the attention of Bar/None Records, a respected independent label based in Hoboken, New Jersey. Freedy Johnston made his recording debut in 1989 with two tracks on a Bar/None label sampler, Time For A Change, and his first album, the scrappy and genially eccentric The Trouble Tree, followed in 1990. While the album received largely positive reviews and became a minor hit in Holland, sales were poor in the United States, and in order to finance recording of his second album, Johnston was forced to sell some farmland that had been with the Johnston family for generations (a decision Johnston set to music in his song "Trying to Tell You I Don't Know"). However, the risk paid off as 1992's Can You Fly earned enthusiastic reviews and was named among the year's best albums by The New York Times, Billboard, Spin, and Musician Magazine; Robert Christgau in The Village Voice went so far as to call it "a perfect album." The album also earned a healthy amount of alternative radio airplay, and Can You Fly’s success convinced Elektra Records to sign Freedy Johnston. -

2008 Erik Axel Karlfeldt Memorial Open Round 8

2008 Erik Axel Karlfeldt Memorial Open Round 8 1. According to one website, this man had a “brief but heated affair” with Elliot Sanders while at Southeastern Missouri University; that website claims that this man’s third wife agreed not to disclose his homosexuality in a divorce settlement. He used the pseudonym “Jeff Christie” early in his career, and worked for the Kansas City Royals before moving to Sacramento and becoming successful in a different field. He had a TV show in the ‘90s which was produced by Roger Ailes, while his more recent achievements include “Operation Chaos,” in which he allegedly inspired Democrats to vote for Hillary Clinton. His addiction to prescription painkillers was exposed in 2003. FTP, name this leader of the “Dittoheads,” a conservative radio host. ANSWER: Rush Limbaugh 2. The episode “One of Our Running Backs is Missing” saw the main character of this show save a kidnapped football player played by Larry Csonka, while the episode “Burning Bright” featured William Shatner as an astronaut with special powers. Andy in The 40 Year Old Virgin has an action figure of the boss of the main character of this series. The main character was employed by the Office of Scientific Investigation, and this series originated the character of Jaime Sommers. The main character on this show, who was horribly injured in a plane crash, was played by Lee Majors. FTP, name this show which centered on the “Better, Stronger, Faster” Steve Austin, the titular bionic figure. ANSWER: The Six Million Dollar Man 3. “A Little Bluer Than That” was the second track on a 2002 album of this name.