Consuming the Reality TV Wedding Renee Sgroi

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bachelor Pad 2’ Recap Episode 2: Ames Brown Trumps Them All by Lori Bizzoco

Tara Reid: Engaged and Married All In One Day Just hours after tweeting that she “just got engaged,” Tara Reid tied the knot with her fiancé Zack Kehayov in Greece on Saturday. UsMagazine.com reported that the American Reunion actress recently split from her boyfriend Michael Lilleun. She was also previously engaged to Internet entrepreneur Michael Axtmann, but called it off in April 2010. Even further back, she was engaged to Carson Daly — The Voice host — and they ended their relationship in June 2001. Things might be happening very quickly for Reid, but we wish her all the best. What are the advantages to eloping? Cupid’s Advice: Weddings are expensive and can be stressful to plan. Here is why Cupid thinks eloping can be the best decision for you: 1. Cost: Couples who elope will pay a nominal fee compared to those who have a wedding. Marriage licenses range from $10 (Colorado) to $100 (Minnesota). Your other expenses will only be your outfit, transportation and lodging. 2. No stress: Planning a wedding is stressful. If you elope, you won’t be overwhelmed because all you have to plan is when and where you want to marry the one you love. 3. Avoid drama: If your parents object to the marriage, then avoid the drama the wedding will cause. By eloping, you’ll have a simpler ceremony and won’t have to deal with people who don’t support you both. Do you think it’s a good idea for couples to elope? Let us know about your thoughts by commenting below. -

Information Guide

INFORMATION GUIDE 7 ALL-PRO 7 NFL MVP LAMAR JACKSON 2018 - 1ST ROUND (32ND PICK) RONNIE STANLEY 2016 - 1ST ROUND (6TH PICK) 2020 BALTIMORE DRAFT PICKS FIRST 28TH SECOND 55TH (VIA ATL.) SECOND 60TH THIRD 92ND THIRD 106TH (COMP) FOURTH 129TH (VIA NE) FOURTH 143RD (COMP) 7 ALL-PRO MARLON HUMPHREY FIFTH 170TH (VIA MIN.) SEVENTH 225TH (VIA NYJ) 2017 - 1ST ROUND (16TH PICK) 2020 RAVENS DRAFT GUIDE “[The Draft] is the lifeblood of this Ozzie Newsome organization, and we take it very Executive Vice President seriously. We try to make it a science, 25th Season w/ Ravens we really do. But in the end, it’s probably more of an art than a science. There’s a lot of nuance involved. It’s Joe Hortiz a big-picture thing. It’s a lot of bits and Director of Player Personnel pieces of information. It’s gut instinct. 23rd Season w/ Ravens It’s experience, which I think is really, really important.” Eric DeCosta George Kokinis Executive VP & General Manager Director of Player Personnel 25th Season w/ Ravens, 2nd as EVP/GM 24th Season w/ Ravens Pat Moriarty Brandon Berning Bobby Vega “Q” Attenoukon Sarah Mallepalle Sr. VP of Football Operations MW/SW Area Scout East Area Scout Player Personnel Assistant Player Personnel Analyst Vincent Newsome David Blackburn Kevin Weidl Patrick McDonough Derrick Yam Sr. Player Personnel Exec. West Area Scout SE/SW Area Scout Player Personnel Assistant Quantitative Analyst Nick Matteo Joey Cleary Corey Frazier Chas Stallard Director of Football Admin. Northeast Area Scout Pro Scout Player Personnel Assistant David McDonald Dwaune Jones Patrick Williams Jenn Werner Dir. -

APEX: Hannah Piper Burns a Conversation

HANNAH PIPER BURNS Venus Retrograde February 24 – August 12, 2018 Your Host, 2017 Your Host, 2017 False Idylls, 2017 APEX: HANNAH PIPER BURNS A conversation How did you first embark on the material of these reality shows— You pull out multiple dimensions of time from these reality Bachelor in Paradise, The Bachelor, and The Bachelorette—for shows: the timeline of filming a season, the contestants’ siloed your subject? How has your work changed over the course of perspectives, and the broader sense of time from the viewers nearly ten years you’ve worked on these materials? who have access to multiple contestant viewpoints. I have been watching these shows and their spinoffs since The ways that these shows warp and manipulate time, both 2008. Originally, I was compelled by the baroque banality of real- for the viewers and the contestants are myriad! It’s like how ity television, as well as its holistic commitment to failure. But gravity behaves on other planets: six weeks in Bachelor Nation is the deaths of two former contestants on the show—Gia Allemand the equivalent of eighteen Earth days. Then of course there’s the in 2013 and Eric Hill in 2014—catalyzed something in me. The lapse in time between a contestant’s experiences of their lived and first pieces I made with this material are in a very real sense mediated realities, and the somewhat unpredictable period after tributes to Eric and Gia. While making them, other aspects of the show airs but while they are again under intense surveillance— the footage began to speak to me, especially the parts that served now in “real” time. -

Reality TV Personality Chris Harrison Partners with Seagram's Escapes: New Flavor Seagram's Escapes Tropical Rosé to Hit Sh

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Media Contact: Cheryl McLean 323-512-3822 [email protected] Reality TV Personality Chris Harrison Partners with Seagram’s Escapes: New Flavor Seagram’s Escapes Tropical Rosé to Hit Shelves this February Rochester, NY – One of reality TV’s most beloved stars is teaming up with one of America’s favorite alcoholic beverage brands, and they’re a perfect match. Reality TV host and social media giant, Chris Harrison, is expanding into the alcoholic beverage space with a brand-new Seagram’s Escapes flavor: Tropical Rosé. The rosé style drink has just 100 calories, similar to seltzers, but is packed with much more taste and made with natural passion fruit and dragon fruit flavors. Tropical Rosé clocks in at 3.2 percent alcohol-by-volume and will be available nationally in four packs of 12-ounce cans starting in February. Harrison has been fully immersed in what is his first alcohol partnership, working closely with the Seagram’s Escapes team to craft the new drink’s flavor, name and packaging. “Creating Tropical Rosé has been a really hands-on experience for me,” said Harrison. “From the very beginning, I traveled with the Seagram’s Escapes team to their flavor house in Chicago to pick just the right color and the perfect fruit flavors. After we were happy with the drink, I had the opportunity to choose the name and weigh in on everything from packaging to advertising. I’m proud of Tropical Rosé and can’t wait for everyone to finally taste it.” “We’re thrilled to have had the opportunity to partner with Chris and to share this drink with both our fans and his,” said Lisa Texido, Seagram’s Escapes brand manager. -

The Unbearable Whiteness of ABC: the First Amendment, Diversity, and Reality Television in the Wake of Claybrooks V. ABC

SMU Law Review Volume 66 Issue 2 Article 10 2013 The Unbearable Whiteness of ABC: The First Amendment, Diversity, and Reality Television in the Wake of Claybrooks v. ABC Sarah Honeycutt Southern Methodist University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.smu.edu/smulr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Sarah Honeycutt, Note, The Unbearable Whiteness of ABC: The First Amendment, Diversity, and Reality Television in the Wake of Claybrooks v. ABC, 66 SMU L. REV. 431 (2013) https://scholar.smu.edu/smulr/vol66/iss2/10 This Case Note is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at SMU Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in SMU Law Review by an authorized administrator of SMU Scholar. For more information, please visit http://digitalrepository.smu.edu. THE UNBEARABLE WHITENESS OF ABC: THE FIRST AMENDMENT, DIVERSITY, AND REALITY TELEVISION IN THE WAKE OF CLAYBROOKS v. ABC Sarah Honeycutt* TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION... .................. ....... 432 II. HISTORICAL INTERSECTIONS BETWEEN THE FIRST AMENDMENT AND DIVERSITY ............ 433 A. FIRST AMENDMENT FREEDOM OF SPEECH ............. 433 B. FIRST AMENDMENT FREEDOM OF CONDUCT........... 434 C. BALANCING FREE SPEECH AND DIVERSITY ............ 435 1. Free Speech over Diversity .................... 435 2. Diversity over Free Speech .................... 435 D. OTHER DISCRIMINATION SAFEGUARDS ................ 439 1. Title VII ................................. 439 2. Section 1981 ... ............................... 440 III. CURRENT LAW: "THE BACHELOR" CONTROVERSY............. ................. 440 . A. WHAT IS "THE BACHELOR"? . 441 B. WHO ARE NATHANIEL CLAYBROOKS AND . CHRISTOPHER JOHNSON? . 442 C. THE LAWSUIT ......................................... 442 IV. WHERE DO WE GO FROM HERE? ................ 446 A. MORE LAWSUITS: CHALLENGING THE CLAYBROOKS COURT'S APPLICATION OF HURLEY AND GAINING PUBLICITY............................................ -

Series Premiere

Jan. 29, 2018 SERIES PREMIERE LET THE WINTER GAMES BEGIN! BACHELOR NATION BECOMES BACHELOR WORLD WHEN ADVENTUROUS ROMANTICS FROM AROUND THE GLOBE SEARCH FOR LOVE AMIDST FRIENDLY COMPETITION, ON ABC’S ‘THE BACHELOR WINTER GAMES’ The Premiere Episode Highlights an Appearance From Bachelor Nation Alumni Trista and Ryan Sutter and a Performance by Country Singer/Songwriter Ruthie Collins Photo credit: ABC/Lorenzo Bevilaqua* For high-res photos, click here. “Episode 101” – Baby, it’s cold outside when 25 bachelors and bachelorettes from around the world meet in the streets of Manchester, Vermont, for a grand celebration of unity and love on the premiere of the new highly anticipated four-episode series, “The Bachelor Winter Games,” beginning TUESDAY, FEB. 13 (8:00-10:00 p.m. EST), on The ABC Television Network, streaming and on demand. Chris Harrison hosts with ESPN SportsCenter anchor and sports journalist Hannah Storm and KABC-TV sports anchor and correspondent Ashley Brewer there to help report on all of the exciting action. Bachelor royalty Trista and Ryan Sutter make a special appearance, serving as grand marshals to kick off the festivities. Following a featured performance by up-and-coming country music sensation Ruthie Collins, the singles move into their Bachelor villa at The Hermitage Club at Haystack Mountain in Wilmington, Vermont, and the games of love begin. Back at the Bachelor villa, Chris Harrison reveals that the winter challenges will begin with a biathlon the next morning. Only the male and female winners will be awarded a date card and the opportunity to ask a potential love interest on a romantic escapade. -

The Reinforcement of Stereotypical Gender Roles On

Living Happily Ever After? : The Reinforcement of Stereotypical Gender Roles on The Bachelor and The Bachelorette Erin Victoria Klewin William E. Stanwood, Thesis Advisor Boston College May 2007 Acknowledgments There have been many people over the past year who have in one way or another helped and participated in the creation of this senior thesis. First and foremost, I dedicate this thesis to my family for encouraging me to undertake this project and challenge myself, and for helping me push through even at the most stressful of times. They have given me endless love and support my entire life and have never stopped believing in me, and I am eternally thankful to them. I also want to thank my advisor, Professor Bill Stanwood, for his countless hours of guidance, support and optimism. Coming in as my advisor later than normal, he has been optimistic and excited about this project from day one. Constantly available and willing to help, he has had such confidence in my abilities. This thesis would not be what it is today if not for Professor Stanwood’s direction and continual support, and I feel privileged to have had him as my advisor. Finally, I want to thank the Communication Department and the Arts & Sciences Honors Program of Boston College for affording me the opportunity to engage in such a challenging yet fulfilling project. It has been a tremendous learning experience and one which I am incredibly thankful for! i Table of Contents Abstract.............................................................................................................................. -

QEP Focuses on Students' Concerns Martinson and Qubein: Men Of

A&E: Ruler's responsibilities... fWlWQ HIGH POINT UNIVERSITY Campus Chronicle FRIDAY. March 24. 2006 HIGH POINT, N.C QEP focuses on students' concerns By Briana Warner present here at High Point, but they have that the president delivered the week be- University English Staff Writer been on the periphery," said Dr. Jeffrey fore. For example, if the message of the Adams, director of Institutional Advance- president's seminar is related to health and professor In the fall of 2005, administrators ment and author of the QEP "The pur- wellness, students might travel the next sent an e-mail to all students asking the pose of the QEP is to take those programs week to High Point Regional Hospital to publishes question "If High Point University could out of the shadows and make them a fo- complete their civic engagement activity. English professor Dr. Ed do one thing to improve your experience, cus of our students' education." Students will then write a short essay Piacentino recently published a book what would it be?" Preliminary work with the QEP has about their experience and the connection and several articles. His book, entitled Some students probably deleted the already begun with planning and the ap- between the lecture and the experience. "The Enduring Legacy of Old South- e-mail without reading it. Others perhaps pointment of Dr. Kelly Norton as the new During the sophomore year begin- west Humor," explores modern and read it and decided that they didn't have director of Experiential Learning. Phase ning in 2007-2008, phase II of the QEP, contemporary southern writers like time to formulate an answer to the ques- I of the QEP will begin in the fall of 2006 the civic engagement requirement will be William Faulkner and Zora Neale tion. -

Lakeshore Shipyard Property

Dan and Deanna Maki 90 percent chance of rain Web: www.lakequip.com akeshore High: 52 | Low: 40 | Details, page 2 EQUIPMENTakeshore & LTRUCK SALES Inc. LBusiness 906-229-5063 4 Industrial Park Wakefield, MI 49968 Located off US 2 DAILY GLOBE yourdailyglobe.com Tuesday, October 15, 2013 75 cents Ironwood to host pair of snowmobile events uary. fair and Friends of the Fair. day, the commission approved a 2013- DiGiorgio said another change is n Vintage, professional In addition to the traditional snow- The commission granted the request. 14 snowmobile map, which is mostly access on Lawrence Street will be circuits to visit mobile vintage races on Jan. 3-5, profes- “It’s going to bring a lot of people unchanged from last year. closed, but trail access is available near sional racing from the U.S. Snowmobile into town,” Auvinen said. Ironwood Public Safety Department there. fairgrounds on first two Association is scheduled for Jan. 11-12, He said more information on the Director Andrew DiGiorgio said the The commission prepared for winter January weekends according to Tom Auvinen. He appeared Snowmobile Olympus is available at biggest change in the new map is open- by accepting a bid for 4,000 tons of before the Ironwood City Commission ironwoodsnowmobileolympus.com, a ing the trail from Lake Street to the street sand from Jake’s Excavating for By RALPH ANSAMI Monday with Jim Gribble to request a special website designed by Jim Saari Holiday Station, where the machine $29,250. A lower bid from Snow Coun- [email protected] special water rate reduction for the that was set up last week. -

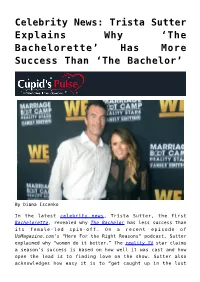

Trista Sutter Explains Why ‘

Celebrity News: Trista Sutter Explains Why ‘The Bachelorette’ Has More Success Than ‘The Bachelor’ By Diana Iscenko In the latest celebrity news, Trista Sutter, the first Bachelorette, revealed why The Bachelor has less success than its female-led spin-off. On a recent episode of UsMagazine.com’s “Here For the Right Reasons” podcast, Sutter explained why “women do it better.” The reality TV star claims a season’s success is based on how well it was cast and how open the lead is to finding love on the show. Sutter also acknowledges how easy it is to “get caught up in the lust factor.” In the franchise’s history, sixBachelorettes are still with their season’s winner, while only one Bachelor is married to his season’s winner. Several Bachelors have ended up with someone from their season after proposing to someone else. In celebrity news, Trista Sutter opens up about why The Bachelorette has more success stories than The Bachelor. What are some ways to tell the difference between lust and love? Cupid’s Advice: The start of a new relationship is exciting! It’s easy to get swept up with a new partner, but are you excited for the right reasons? If you’re not sure if you’re in love or in lust, Cupid has some advice for you. 1. You enjoy talking to them: Anyone in a new relationship will want to see their partner, but talking over the phone consistently might show that there’s a deeper level of connection. If you only talk to your new partner while seeing them in person, love may be taking a backseat to lust. -

W Network's the Bachelorette Canada Introduces Jasmine Lorimer

W Network’s The Bachelorette Canada Introduces Jasmine Lorimer as Canada’s First-Ever Bachelorette Canadian Actor and Television Star Noah Cappe to Host the Series #BacheloretteCA Premieres This Fall on W Network Photo credit: Erich Saide Hi-res images of Jasmine Lorimer and Noah Cappe are available here. For Immediate Release TORONTO, June 9, 2016 – The wait is finally over, Canada. As revealed on Entertainment Tonight Canada, Kenora, Ontario-native Jasmine Lorimer is putting her heart on the line this fall on W Network’s The Bachelorette Canada. Lorimer, a hairstylist currently based out of Pemberton, British Columbia, will search for the man of her dreams when 20 eligible bachelors do whatever it takes to win her heart. By her side throughout the journey will be host Noah Cappe, who is best known for his roles on Food Network Canada’s Carnival Eats, The Great Canadian Cookbook and W Network’s top-rated series Good Witch. The smash-hit reality series premieres this fall on W Network. "It is such an honour to be Canada's first bachelorette," says Jasmine Lorimer. "This opportunity came at the perfect time for me and I couldn't be more prepared to embark upon this lifelong adventure." A small-town girl at heart, 27 year-old Lorimer’s artistic nature and adventurous spirit drew her to the beauty industry and the West Coast. Her free spirited, down-to-earth approach to life, coupled with a warm and radiant disposition, make Jasmine the perfect choice for this romantic adventure of a lifetime. Refreshingly open, honest and not afraid to laugh at herself, Canadians nationwide will fall in love with Jasmine as she risks it all to find “the one.” In the Canadian version of this widely successful reality series, Jasmine Lorimer is in search of her soul mate – and hopefully her groom-to-be. -

Trista Sutter Surprises Husband Ryan with Colorado Camping Trip

Trista Sutter Surprises Husband Ryan With Colorado Camping Trip By Maggie Manfredi Bachelorette alums find their own slice of paradise! According to Usmagazine.com, Trista Sutter surprised Ryan Sutter with a family trip to Colorado for his birthday. The parents of two met in 2003 on The Bachelorette. The firefighter was showered in gifts from paddle boards to social media shout outs from his wife. The family kept it country with a brand new Airstream, camping fun, and lake activities. What are three creative birthday gifts for your partner? Cupid’s Advice: Are you struggling to think of something new and exciting to give to your love this year? Never fear; Cupid has some great gift ideas for you to make this a memorable birthday celebration: 1. Instagram fun: Take a look back at his pictures from the year and turn them into tangible memories. Think outside the box not just a picture in a frame: magnets, coasters, stickers, postcards anything that your partner would love! Related: Sean Lowe Writes: “My Wife Is Hot and I’m in Love” 2. New experience: If you are planning to take your significant other away, try something new. See animals or go to a historical place; try a new sport or exotic cuisine. Take them on a wild birthday adventure that they will never forget. Related: Jessica Simpson Says She’s Done Having Kids with Eric Johnson 3. Show you care: With all the technologies of today making a birthday video would be fun and sweet. You can even get relatives and friends involved, especially if they are far away.