University of Florida Thesis Or Dissertation Formatting

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Back on the Glory Trail Setting Sail Sea the Stars

SUNDAY, MAY 12, 2013 732-747-8060 $ TDN Home Page Click Here BACK ON THE GLORY TRAIL SEA THE STARS COLT SMASHES RECORD The sound of deflation following the defeat of Europe=s Breeze-Up carnival descended upon Saint- Toronado (Ire) in last Saturday=s G1 2000 Guineas Cloud yesterday and Arqana=s record book was torn could be heard far afield, but his less flashy stable asunder within the first hour of trade as a Sea the Stars companion Olympic Glory (Ire) (Choisir {Aus}) can put (Ire) colt, already named Salamargo (Ire), broke through some pep back in the step of trainer Richard Hannon if the half-million barrier to set a new benchmark when he can overcome a wide draw in today=s G1 Poule selling to Newmarket conditioner Marco Botti, acting on d=Essai des Poulains at behalf of Sheikh Mohammed bin Khalifa Al Maktoum, Longchamp. Tasting defeat for i520,000. Offered by Alban Chevalier du Fau and only once so far on only his Jamie Railton=s The Channel Consignment as Hip 13, second start at the hands of the February-foaled bay, who is out of the dual stakes Dawn Approach (Ire) (New winner Navajo Moon (Ire) (Danehill), returned a Approach {Ire}) in Royal handsome profit on the i200,000 he cost when Ascot=s G2 Coventry S. in passing through the Deauville ring at last year=s August Olympic Glory June, Sheikh Joaan bin Hamad Yearling Sale. AI have three juveniles by his sire with Racing Post Al Thani=s likeable colt seemed me, and he is probably one of the best I=ve seen,@ Botti to find winning coming easily told Racing Post. -

Headline News

SILENT NAME TO ADENA SPRINGS HEADLINE p9 NEWS For information about TDN, DELIVERED EACH NIGHT BY FAX AND FREE BY E-MAIL TO SUBSCRIBERS OF call 732-747-8060. www.thoroughbreddailynews.com FRIDAY, SEPTEMBER 29, 2006 SANDER QUANDARY SADLER’S DUO BREAK MILLION BARRIER With the rain clouds gathering above Newmarket, Goffs rounded off its flagship Million Sale in style connections of Europe’s top-rated filly Sander Camillo yesterday when two lots reached beyond the magic (Dixie Union) approach today’s G1 Cheveley Park S. in million-euro mark. Topping the session and the sale apprehensive mood. Highly impressive when winning overall at i2 million was hip 627, a sister to this year’s the G3 Albany S. and G2 G1 Epsom Derby runner-up Dragon Dancer (GB). De- Cherry Hinton S. on a sum- spite her obvious potential for the track, the May-foaled mer surface, Sir Robert daughter of Sadler’s Wells Ogden’s leading lady may consigned by Kirsten have to answer a different Rausing’s Staffordstown Stud question in this contest. has significant residual value “The filly is in great form, as a broodmare prospect. Her but we are in the lap of the third dam is the outstanding gods regarding the Alruccaba (Ire), who has es- Sander Camillo channel4.com weather,” commented tablished a dynasty of top- trainer Jeremy Noseda, who class performers in a short is looking for his third renewal following the exploits of space of time. Among her Wannabe Grand (GB) in 1998 and Carry on Katie three progeny is the 1996 G2 years ago. -

NP 2013.Docx

LISTE INTERNATIONALE DES NOMS PROTÉGÉS (également disponible sur notre Site Internet : www.IFHAonline.org) INTERNATIONAL LIST OF PROTECTED NAMES (also available on our Web site : www.IFHAonline.org) Fédération Internationale des Autorités Hippiques de Courses au Galop International Federation of Horseracing Authorities 15/04/13 46 place Abel Gance, 92100 Boulogne, France Tel : + 33 1 49 10 20 15 ; Fax : + 33 1 47 61 93 32 E-mail : [email protected] Internet : www.IFHAonline.org La liste des Noms Protégés comprend les noms : The list of Protected Names includes the names of : F Avant 1996, des chevaux qui ont une renommée F Prior 1996, the horses who are internationally internationale, soit comme principaux renowned, either as main stallions and reproducteurs ou comme champions en courses broodmares or as champions in racing (flat or (en plat et en obstacles), jump) F de 1996 à 2004, des gagnants des neuf grandes F from 1996 to 2004, the winners of the nine épreuves internationales suivantes : following international races : Gran Premio Carlos Pellegrini, Grande Premio Brazil (Amérique du Sud/South America) Japan Cup, Melbourne Cup (Asie/Asia) Prix de l’Arc de Triomphe, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth Stakes, Queen Elizabeth II Stakes (Europe/Europa) Breeders’ Cup Classic, Breeders’ Cup Turf (Amérique du Nord/North America) F à partir de 2005, des gagnants des onze grandes F since 2005, the winners of the eleven famous épreuves internationales suivantes : following international races : Gran Premio Carlos Pellegrini, Grande Premio Brazil (Amérique du Sud/South America) Cox Plate (2005), Melbourne Cup (à partir de 2006 / from 2006 onwards), Dubai World Cup, Hong Kong Cup, Japan Cup (Asie/Asia) Prix de l’Arc de Triomphe, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth Stakes, Irish Champion (Europe/Europa) Breeders’ Cup Classic, Breeders’ Cup Turf (Amérique du Nord/North America) F des principaux reproducteurs, inscrits à la F the main stallions and broodmares, registered demande du Comité International des Stud on request of the International Stud Book Books. -

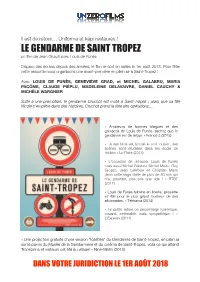

LE GENDARME DE SAINT TROPEZ Un film De Jean Girault Avec Louis De Funès

! Il est de retour… Uniforme et képi restaurés ! LE GENDARME DE SAINT TROPEZ un film de Jean Girault avec Louis de Funès Disparu des écrans depuis des années, le film re-sort en salles le 1er août 2018. Pour fêter cette ressortie nous organisons une avant-première en plein air à Saint-Tropez ! Avec LOUIS DE FUNÈS, GENEVIÈVE GRAD, et MICHEL GALABRU, MARIA PACÔME, CLAUDE PIÉPLU, MADELEINE DELAVAIVRE, DANIEL CAUCHY & MICHÈLE WARGNIER Suite à une promotion, le gendarme Cruchot est muté à Saint-Tropez ; alors que sa fille Nicole s'empêtre dans des histoires, Cruchot prend la tête des opérations… « Amateurs de bonnes blagues et des grimaces de Louis de Funès, sachez que le gendarme est de retour. » France 3 (2018) « A ses films est accolé le mot ‘cultes’, ses scènes sont étudiées dans les école de théâtre » Le Point (2018) « L'occasion de retrouver Louis de Funès mais aussi Michel Galabru, Michel Modo, Guy Grosso, Jean Lefebvre et Christian Marin dans cette saga vieille de plus de 50 ans qui n'a, pourtant, pas pris une ride ! » RTBF (2017) « Louis de Funès fulmine en liberté, pirouette et râle pour le plus grand bonheur de ses aficionados. » Télérama (2014) « Le public adore ce personnage tyrannique, couard, détestable mais sympathique ! » L’Express (2011) « Une projection gratuite d'une version "toilettée" du Gendarme de Saint-Tropez, en plein air sur le parvis du Musée de la Gendarmerie et du cinéma de Saint-Tropez, voilà ce qui attend Tropéziens et visiteurs cet été au village! « Nice-Matin (2018) DANS VOTRE JURIDICTION LE 1ER AOÛT 2018 ! TRAVAUX D’IMAGE ET DE SON Pour cette sortie cinéma en 2018 SNC et M6 ont entamé une restauration photochimique et une restauration en 4K. -

Preliminaires 11 D”Cembre

Preliminaires 11 décembre 15/11/07 17:28 Page 1 DEAUVILLE Vente de 272 Yearlings sans réserve Sale of 272 Yearlings without reserve 2007 Mercredi 12 décembre : 11 h 00 (11.00 a.m.) En couverture : Cover : Exotic Dancer champion sur les obstacles en Angleterre Exotic Dancer, a Champion over jumps in England et Stoneside gagnant de groupes et placé de Gr.1 ; and Stoneside, a Group winner and Group 1 performer, vendus yearlings en décembre à Deauville. were both sold as yearlings in Deauville in December. © Photos : A.P.R.H.– Jean-Charles BRIENS ARQANA Deauville 32, avenue Hocquart de Turtot B.P. 23100 - 14803 Deauville Cedex Tél. : 02.31.81.81.00 - Fax : 02.31.81.81.01 - www.arqana.com - [email protected] S.A.S. au Capital de 7 443 390 € - Siège social : 32, av. Hocquart de Turtot - 14800 Deauville R.C.S. Honfleur 438 241 788 Bernard de Reviers Commissaire-priseur habilité Société de ventes volontaires aux enchères publiques agréée en date du 8 mars 2007 sous le no 2007-613 en association avec Preliminaires 11 décembre 15/11/07 15:55 Page 2 Calendrier des Ventes 2008* 2008 Sales calendar* Deauville 19 ET 20 FÉVRIER Vente Mixte FEBRUARY 19 AND 20 Mixed Sale DU 15 AU 18 AOÛT Vente de Yearlings AUGUST 15-18 Yearling Sale DU 20 AU 22 OCTOBRE Vente de Yearlings OCTOBER 20-22 Yearling Sale DU 6 AU 9 DÉCEMBRE Vente d'Elevage DECEMBER 6-9 Breeding Stock Sale 10 DÉCEMBRE Vente de Yearlings DECEMBER 10 Yearling Sale Saint-Cloud 18 ET 19 AVRIL Vente de 2 ans montés APRIL18-19 2 y-o Breeze-Up 19 AVRIL Chevaux à l’entraînement APRIL 19 Horses in training -

Le Gendarme.Wps

Un jour de 1963, Richard Balducci, producteur, roule en décapotable entre Sainte Maxime et Saint Tropez, à la recherche d'une villa. Il se fait voler sa caméra. Furieux, il se rend à la gendarmerie de Saint Tropez, place Blanqui, et trouve là un gendarme à l'allure débonnaire qui l'écoute avec attention. Balducci veut porter plainte. Le gendarme 1 lui rétorque : " Mais il est midi ! " Balducci, médusé, ne tient pas à en rester là. Il écrit un synopsis de quelques pages qu'il propose à Louis De Funès, et quelques mois plus tard une équipe de tournage débarque à Saint Tropez. Dans Le gendarme... Louis de Funès est dirigé par Jean Girault avec lequel il a réalisé Pouic Pouic et Faite sauter la banque. Le film sort en salle en septembre 1964 et, en très peu de temps, il cartonne. Le public adore ce personnage tyrannique, couard, détestable mais sympathique ! 2 Face au succès du Gendarme à Saint Tropez, une suite, puis quatre autres sont envisagées : Le Gendarme à New York, Le Gendarme se marie, Le gendarme en balade, Le Gendarme et les Extraterrestres et enfin Le Gendarme et les Gendarmettes. - M. Balducci comment en êtes vous arrivé à travailler dans le cinéma ? 3 - C'est très simple. J'ai commencé par être journaliste, notamment pour France Soir, et j'écrivais dans la rubrique cinéma. C'est comme cela que la passion m'est venue. J'ai fait quelques films en tant qu'acteur mais mon but principal était l'écriture. J'étais en fait acteur quand il fallait remplacer quelqu'un (rires) ! - Vous êtes à l'origine d'un grand nombre de films extrêmement populaires tels que la saga des "Gendarme" ou "Le facteur de Saint-Tropez" pour ne citer qu'eux, il est 4 bien évidemment touchant de voir que l'accueil du public, plusieurs années après, est resté intact ? - Oui bien sûr, cela me fait très plaisir, il y a une forme de fidélité qui est vraiment touchante notamment de la part des jeunes personnes. -

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist Ein Karaokesystem der Firma Showtronic Solutions AG in Zusammenarbeit mit Karafun. Karaoke-Katalog Update vom: 13/10/2020 Singen Sie online auf www.karafun.de Gesamter Katalog TOP 50 Shallow - A Star is Born Take Me Home, Country Roads - John Denver Skandal im Sperrbezirk - Spider Murphy Gang Griechischer Wein - Udo Jürgens Verdammt, Ich Lieb' Dich - Matthias Reim Dancing Queen - ABBA Dance Monkey - Tones and I Breaking Free - High School Musical In The Ghetto - Elvis Presley Angels - Robbie Williams Hulapalu - Andreas Gabalier Someone Like You - Adele 99 Luftballons - Nena Tage wie diese - Die Toten Hosen Ring of Fire - Johnny Cash Lemon Tree - Fool's Garden Ohne Dich (schlaf' ich heut' nacht nicht ein) - You Are the Reason - Calum Scott Perfect - Ed Sheeran Münchener Freiheit Stand by Me - Ben E. King Im Wagen Vor Mir - Henry Valentino And Uschi Let It Go - Idina Menzel Can You Feel The Love Tonight - The Lion King Atemlos durch die Nacht - Helene Fischer Roller - Apache 207 Someone You Loved - Lewis Capaldi I Want It That Way - Backstreet Boys Über Sieben Brücken Musst Du Gehn - Peter Maffay Summer Of '69 - Bryan Adams Cordula grün - Die Draufgänger Tequila - The Champs ...Baby One More Time - Britney Spears All of Me - John Legend Barbie Girl - Aqua Chasing Cars - Snow Patrol My Way - Frank Sinatra Hallelujah - Alexandra Burke Aber Bitte Mit Sahne - Udo Jürgens Bohemian Rhapsody - Queen Wannabe - Spice Girls Schrei nach Liebe - Die Ärzte Can't Help Falling In Love - Elvis Presley Country Roads - Hermes House Band Westerland - Die Ärzte Warum hast du nicht nein gesagt - Roland Kaiser Ich war noch niemals in New York - Ich War Noch Marmor, Stein Und Eisen Bricht - Drafi Deutscher Zombie - The Cranberries Niemals In New York Ich wollte nie erwachsen sein (Nessajas Lied) - Don't Stop Believing - Journey EXPLICIT Kann Texte enthalten, die nicht für Kinder und Jugendliche geeignet sind. -

Rwitc, Ltd. Annual Auction Sale of Two Year Old Bloodstock 142 Lots

2020 R.W.I.T.C., LTD. ANNUAL AUCTION SALE OF TWO YEAR OLD BLOODSTOCK 142 LOTS ROYAL WESTERN INDIA TURF CLUB, LTD. Mahalakshmi Race Course 6 Arjun Marg MUMBAI - 400 034 PUNE - 411 001 2020 TWO YEAR OLDS TO BE SOLD BY AUCTION BY ROYAL WESTERN INDIA TURF CLUB, LTD. IN THE Race Course, Mahalakshmi, Mumbai - 400 034 ON MONDAY, Commencing at 4.00 p.m. FEBRUARY, 03RD (LOT NUMBERS 1 TO 71) AND TUESDAY, Commencing at 4.00 p.m. FEBRUARY, 04TH (LOT NUMBERS 72 TO 142) Published by: N.H.S. Mani Secretary & CEO, Royal Western India Turf Club, Ltd. eistere ce Race Course, Mahalakshmi, Mumbai - 400 034. Printed at: MUDRA 383, Narayan Peth, Pune - 411 030. IMPORTANT NOTICES ALLOTMENT OF RACING STABLES Acceptance of an entry for the Sale does not automatically entitle the Vendor/Owner of a 2-Year-Old for racing stable accommodation in Western India. Racing stable accommodation in Western India will be allotted as per the norms being formulated by the Stewards of the Club and will be at their sole discretion. THIS CLAUSE OVERRIDES ANY OTHER RELEVANT CLAUSE. For application of Ownership under the Royal Western India Turf Club Limited, Rules of Racing. For further details please contact Stipendiary Steward at [email protected] BUYERS BEWARE All prospective buyers, who intend purchasing any of the lots rolling, are requested to kindly note:- 1. All Sale Forms are to be lodged with a Turf Authority only since all foals born in 2018 are under jurisdiction of Turf Authorities with effect from Jan . -

Costa-Gavras: a Retrospective

The Museum of Modern Art For Immediate Release March 1990 COSTA-GAVRAS: A RETROSPECTIVE April 13 - 24, 1990 A complete retrospective of twelve feature films by Costa-Gavras, the Greek-born French filmmaker, opens at The Museum of Modern Art on April 13, 1990. Both thought provoking and entertaining, Costa-Gavras's suspenseful mysteries deal with compelling social issues and are often based on actual political incidents. His stories involve the motivations and misuses of power and often explore the concept of trust in personal and public relationships. His films frequently star such popular actors as Fanny Ardant, Jill Clayburgh, Jessica Lange, Jack Lemmon, Yves Montand (who stars in six of the films), Simone Signoret, Sissy Spacek, and Debra Winger. Opening with Z (1969), one of his best-known works, COSTA GAVRAS: A RETROSPECTIVE continues through April 24. New prints of Costa-Gavras's early French films have been made available for this retrospective. These include his first film, The Sleeping Car Murders (1965), a thriller about the hunt for a murderer on an overnight train; the American premiere of the original version of One Man Too Many/Shock Troops (1967), a story of resistance fighters who free a group of political prisoners from a Nazi jail; and Family Business (1986), a drama about the transformation of a family crime ring into the local affiliate of an international syndicate. Also featured are Z (1969), an investigation into the murder of a politician; State of Siege (1972), a fictionalized version of the 1970 kidnapping of an American diplomat in Uruguay; and Special Section -more- 11 West 53 Street, New York, N.Y. -

Susan Bartels Ludvigson Enemy 175 CHARLA 178 BOOK REVIEWS 185 Deborah Kilcollins

LOYOLA UNIVERSI'IY VOLUME 6 NUMBER 2/$2 .50 NEW ORL.EANS REVIEW .· ..,. 0 ' Volume 6 Number 2 NEW ORLEANS REVIEW International Issue NON-FICTION Lucian Blaga The Chronicle and Song of the Ages 99 C. J. McNaspy, S. J. Sn~pets from an Oxford Dia~ 140 John Mosier A onversation with Bertran Tavernier: History with Feeling 156 FICTION Ilse Aichinger The Private Tutor 106 James Ross A House for Senora Lopez 114 Jean Simard An Arsonist 125 Manoj Das The Bridge in the Moonlit Night 148 Antonis Samarakis Mama 167 Ivan Bunin The Rose of Jerico 176 The Book 177 PORTFOLIO Manuel Menan Etchings 133 POETRY Julio Cortazar Restitution 102 After Such Pleasures 103 Happy New Year 104 Gains and Losses Commission 105 Eugenio Montejo Nocturne 109 Pablo Neruda from Stones of the Sky 111 Guiseppe Gioachino Belli The Builders 121 Abraham's Sacrifice 122 Eugenio Montale Almost a Fantasy 124 Sarah Provost Rumor 131 Eduardo Mitre from Lifespace 132 Anna Akhmatova Two Poems 139 Stephanie Naplachowski Bronzed 143 Ernest Ferlita Quetzal 144 Henri Michaux He Writes 151 Karl Krolow In Peacetime 152 William Meissner The Contortionist 154 Robert Bringhurst The Long and Short of it 155 \ Ingebo'lt Bachmann Every Day 163 Andre Pieyre de andiargues Wartime 164 The Friend of Trees 165 The Hearth 165 Michael Andre Bernstein To Go Beyond 169 I Betsy Scholl Urgency 172 How Dreams Come True 173 l Paula Rankin Something Good on the Heels of Something Bad 174 (' Susan Bartels Ludvigson Enemy 175 CHARLA 178 BOOK REVIEWS 185 Deborah Kilcollins 98 i I "I Lucian Blaga THE CHRONICLE AND SONG OF THE AGES -fragments- It was the story of a young man, good and kind, who lived in an unidentifiable village, not far from our own, Village mine, whose name* together ties but in a neighboring county. -

Les Livres Les Films

LES LIVRES LES FILMS Collections de la MEDIATHEQUE DE SAINT-RAPHAEL DOCUMENTS GENERAUX Le rire : essai sur la signification du comique, Henri Bergson Paris, Presses universitaires de France, coll. Bibliothèque de philosophie contemporaine, 1941 Ce livre comprend trois articles sur le rire ou plutôt sur le rire provoqué par le comique. Ils précisent les procédés de fabrication du comique, ses variations ainsi que l'intention de la société quand elle rit. Histoire des spectacles, Guy Dumur, dir. de publication Paris, Gallimard, coll. Encyclopédie de la Pléiade, 1965 Qu'il soit sacré ou profane, divertissant ou exaltant, que le public y joue un rôle ou, au contraire, se contente d'écouter, de regarder, le spectacle, sous toutes ses formes, fait partie de la vie, au point que nous pourrions difficilement concevoir une société où aucune liturgie, aucune fête, aucun jeu, aucune représentation ne viendrait rompre le rythme du quotidien et peut-être lui donner un sens (ou le dépasser) par le pouvoir en quelque sorte magique de l'illusion... Retrouver les origines et retracer l'histoire, dans les diverses civilisations, de ces manifestations artistiques où le singulier quelquefois se distingue mal du collectif dans la mesure où ils ne peuvent se passer l'un de l'autre ; franchir les distances que créent l'espace et le temps afin de discerner le jeu si compliqué des influences ; découvrir, dans les époques dites de transition, le moment où apparaît une forme nouvelle ; tenter de déterminer les modifications, positives ou négatives, de l'art… Résumé http://www.gallimard.fr Le cinéma comique : Encyclopédie du cinéma, vol. -

Michel Serrault (1928-2007) : Le Beau Malentendu

Document generated on 10/01/2021 11:36 p.m. Ciné-Bulles Le cinéma d’auteur avant tout Michel Serrault (1928-2007) Le beau malentendu Nicolas Gendron Volume 26, Number 1, Winter 2008 URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/33488ac See table of contents Publisher(s) Association des cinémas parallèles du Québec ISSN 0820-8921 (print) 1923-3221 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this article Gendron, N. (2008). Michel Serrault (1928-2007) : le beau malentendu. Ciné-Bulles, 26(1), 34–37. Tous droits réservés © Association des cinémas parallèles du Québec, 2008 This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit. Érudit is a non-profit inter-university consortium of the Université de Montréal, Université Laval, and the Université du Québec à Montréal. Its mission is to promote and disseminate research. https://www.erudit.org/en/ PORTRAIT Michel Serrault (1928-2007) Le beau malentendu NICOLAS GENDRON D'un rire franc et jovial, mais d'une grande pudeur, tiste circassien pointant son cœur : « Ça vient de là. Michel Serrault serait le premier à s'amuser que sa Ça ne vient que de là1. » Parallèlement, il ne peut carrière soit désormais citée en exemple, qu'on puisse s'empêcher de tenir en haute estime les dévoués gar vouloir tirer un portrait de lui qui soit sérieux. Parce diens de la foi catholique. C'est ainsi que sa raison que, sur les 135 films auxquels il a contribué, des est partagée entre une carrière de pitre ou de prêtre.