Australian Natural Histflry ~~ .. ~~ ,~

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Barbed Wire Vine

Insects, beetles, bugs and slugs of Mt Gravatt Conservation Reserve Compiled by: Michael Fox www.megoutlook.org/flora-fauna/ © 2015-17 Creative Commons – free use with attribution to Mt Gravatt Environment Group Ants Dolichoderinae Iridomyrmex sp. Small Meat Ant Attendant “Kropotkin” ants with caterpillar of Imperial Hairstreak butterfly. Ants provide protection in return for sugary fluids secreted by the caterpillar. Note the strong jaws. These ants don’t sting but can give a powerful bite. Kropotkin is a reference to Russian biologist Peter Kropotkin who proposed a concept of evolution based on “mutual aid” helping species from ants to higher mammals survive. 22-Aug-17 Insects Beetles and Bugs - ver 5.4 Page 1 of 51 Mt Gravatt Environment Group – www.megoutlook.wordpress.com Insects, beetles, bugs and slugs of Mt Gravatt Conservation Reserve Formicinae Opisthopsis rufithorax Black-headed Strobe Ant 22-Aug-17 Insects Beetles and Bugs - ver 5.4 Page 2 of 51 Mt Gravatt Environment Group – www.megoutlook.wordpress.com Insects, beetles, bugs and slugs of Mt Gravatt Conservation Reserve Formicinae Camponotus consobrinus Banded Sugar Ant Size 10mm Eggs in rotting log Formicinae Camponotus nigriceps Black-headed Sugar Ant 22-Aug-17 Insects Beetles and Bugs - ver 5.4 Page 3 of 51 Mt Gravatt Environment Group – www.megoutlook.wordpress.com Insects, beetles, bugs and slugs of Mt Gravatt Conservation Reserve 22-Aug-17 Insects Beetles and Bugs - ver 5.4 Page 4 of 51 Mt Gravatt Environment Group – www.megoutlook.wordpress.com Insects, beetles, bugs and slugs of Mt Gravatt Conservation Reserve Formicinae Polyrhachis ammon Golden-tailed Spiny Ant Large spines at rear of thorax Nest 22-Aug-17 Insects Beetles and Bugs - ver 5.4 Page 5 of 51 Mt Gravatt Environment Group – www.megoutlook.wordpress.com Insects, beetles, bugs and slugs of Mt Gravatt Conservation Reserve Formicinae Polyrhachis australis Rattle Ant Black Weaver Ant or Dome-backed Spiny Ant Feeding on sugar secretions produced by Redgum Lerp Psyllid. -

Calaby References

Abbott, I.J. (1974). Natural history of Curtis Island, Bass Strait. 5. Birds, with some notes on mammal trapping. Papers and Proceedings of the Royal Society of Tasmania 107: 171–74. General; Rodents; Abbott, I. (1978). Seabird islands No. 56 Michaelmas Island, King George Sound, Western Australia. Corella 2: 26–27. (Records rabbit and Rattus fuscipes). General; Rodents; Lagomorphs; Abbott, I. (1981). Seabird Islands No. 106 Mondrain Island, Archipelago of the Recherche, Western Australia. Corella 5: 60–61. (Records bush-rat and rock-wallaby). General; Rodents; Abbott, I. and Watson, J.R. (1978). The soils, flora, vegetation and vertebrate fauna of Chatham Island, Western Australia. Journal of the Royal Society of Western Australia 60: 65–70. (Only mammal is Rattus fuscipes). General; Rodents; Adams, D.B. (1980). Motivational systems of agonistic behaviour in muroid rodents: a comparative review and neural model. Aggressive Behavior 6: 295–346. Rodents; Ahern, L.D., Brown, P.R., Robertson, P. and Seebeck, J.H. (1985). Application of a taxon priority system to some Victorian vertebrate fauna. Fisheries and Wildlife Service, Victoria, Arthur Rylah Institute of Environmental Research Technical Report No. 32: 1–48. General; Marsupials; Bats; Rodents; Whales; Land Carnivores; Aitken, P. (1968). Observations on Notomys fuscus (Wood Jones) (Muridae-Pseudomyinae) with notes on a new synonym. South Australian Naturalist 43: 37–45. Rodents; Aitken, P.F. (1969). The mammals of the Flinders Ranges. Pp. 255–356 in Corbett, D.W.P. (ed.) The natural history of the Flinders Ranges. Libraries Board of South Australia : Adelaide. (Gives descriptions and notes on the echidna, marsupials, murids, and bats recorded for the Flinders Ranges; also deals with the introduced mammals, including the dingo). -

Insects, Beetles, Bugs and Slugs of Mt Gravatt Conservation Reserve

Insects, beetles, bugs and slugs of Mt Gravatt Conservation Reserve Compiled by: Michael Fox www.megoutlook.org/flora-fauna/ © 2015-20 Creative Commons – free use with attribution to Mt Gravatt Environment Group Ants Dolichoderinae Iridomyrmex sp. Small Meat Ant Attendant “Kropotkin” ants with caterpillar of Imperial Hairstreak butterfly. Ants provide protection in return for sugary fluids secreted by the caterpillar. Note the strong jaws. These ants don’t sting but can give a powerful bite. Kropotkin is a reference to Russian biologist Peter Kropotkin who proposed a concept of evolution based on “mutual aid” helping species from ants to higher mammals survive. 4-Nov-20 Insects Beetles and Bugs - ver 5.9.docx Page 1 of 59 Mt Gravatt Environment Group – www.megoutlook.wordpress.com Insects, beetles, bugs and slugs of Mt Gravatt Conservation Reserve Formicinae Opisthopsis rufithorax Black-headed Strobe Ant Formicinae Camponotus consobrinus Banded Sugar Ant Size 10mm Eggs in rotting log 4-Nov-20 Insects Beetles and Bugs - ver 5.9.docx Page 2 of 59 Mt Gravatt Environment Group – www.megoutlook.wordpress.com Insects, beetles, bugs and slugs of Mt Gravatt Conservation Reserve Formicinae Camponotus nigriceps Black-headed Sugar Ant 4-Nov-20 Insects Beetles and Bugs - ver 5.9.docx Page 3 of 59 Mt Gravatt Environment Group – www.megoutlook.wordpress.com Insects, beetles, bugs and slugs of Mt Gravatt Conservation Reserve Formicinae Polyrhachis ammon Golden-tailed Spiny Ant Large spines at rear of thorax Nest 4-Nov-20 Insects Beetles and Bugs - ver 5.9.docx Page 4 of 59 Mt Gravatt Environment Group – www.megoutlook.wordpress.com Insects, beetles, bugs and slugs of Mt Gravatt Conservation Reserve Formicinae Polyrhachis australis Rattle Ant Black Weaver Ant or Dome-backed Spiny Ant Feeding on sugar secretions produced by Redgum Lerp Psyllid. -

Quaternary Murid Rodents of Timor Part I: New Material of Coryphomys Buehleri Schaub, 1937, and Description of a Second Species of the Genus

QUATERNARY MURID RODENTS OF TIMOR PART I: NEW MATERIAL OF CORYPHOMYS BUEHLERI SCHAUB, 1937, AND DESCRIPTION OF A SECOND SPECIES OF THE GENUS K. P. APLIN Australian National Wildlife Collection, CSIRO Division of Sustainable Ecosystems, Canberra and Division of Vertebrate Zoology (Mammalogy) American Museum of Natural History ([email protected]) K. M. HELGEN Department of Vertebrate Zoology National Museum of Natural History Smithsonian Institution, Washington and Division of Vertebrate Zoology (Mammalogy) American Museum of Natural History ([email protected]) BULLETIN OF THE AMERICAN MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY Number 341, 80 pp., 21 figures, 4 tables Issued July 21, 2010 Copyright E American Museum of Natural History 2010 ISSN 0003-0090 CONTENTS Abstract.......................................................... 3 Introduction . ...................................................... 3 The environmental context ........................................... 5 Materialsandmethods.............................................. 7 Systematics....................................................... 11 Coryphomys Schaub, 1937 ........................................... 11 Coryphomys buehleri Schaub, 1937 . ................................... 12 Extended description of Coryphomys buehleri............................ 12 Coryphomys musseri, sp.nov.......................................... 25 Description.................................................... 26 Coryphomys, sp.indet.............................................. 34 Discussion . .................................................... -

2017 Magdalen College Record

Magdalen College Record Magdalen College Record 2017 2017 Conference Facilities at Magdalen¢ We are delighted that many members come back to Magdalen for their wedding (exclusive to members), celebration dinner or to hold a conference. We play host to associations and organizations as well as commercial conferences, whilst also accommodating summer schools. The Grove Auditorium seats 160 and has full (HD) projection fa- cilities, and events are supported by our audio-visual technician. We also cater for a similar number in Hall for meals and special banquets. The New Room is available throughout the year for private dining for The cover photograph a minimum of 20, and maximum of 44. was taken by Marcin Sliwa Catherine Hughes or Penny Johnson would be pleased to discuss your requirements, available dates and charges. Please contact the Conference and Accommodation Office at [email protected] Further information is also available at www.magd.ox.ac.uk/conferences For general enquiries on Alumni Events, please contact the Devel- opment Office at [email protected] Magdalen College Record 2017 he Magdalen College Record is published annually, and is circu- Tlated to all members of the College, past and present. If your contact details have changed, please let us know either by writ- ing to the Development Office, Magdalen College, Oxford, OX1 4AU, or by emailing [email protected] General correspondence concerning the Record should be sent to the Editor, Magdalen College Record, Magdalen College, Ox- ford, OX1 4AU, or, preferably, by email to [email protected]. -

Globalisation, Human Genomic Research and the Shaping of Health: an Australian Perspective

Globalisation, Human Genomic Research and the Shaping of Health: An Australian Perspective Author Hallam, Adrienne Louise Published 2003 Thesis Type Thesis (PhD Doctorate) School School of Science DOI https://doi.org/10.25904/1912/1495 Copyright Statement The author owns the copyright in this thesis, unless stated otherwise. Downloaded from http://hdl.handle.net/10072/367541 Griffith Research Online https://research-repository.griffith.edu.au Globalisation, Human Genomic Research and the Shaping of Health: An Australian Perspective Adrienne Louise Hallam B.Com, BSc (Hons) School of Science, Griffith University Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy September 2002 Abstract This thesis examines one of the premier “big science” projects of the contemporary era ⎯ the globalised genetic mapping and sequencing initiative known as the Human Genome Project (HGP), and how Australia has responded to it. The study focuses on the relationship between the HGP, the biomedical model of health, and globalisation. It seeks to examine the ways in which the HGP shapes ways of thinking about health; the influence globalisation has on this process; and the implications of this for smaller nations such as Australia. Adopting a critical perspective grounded in political economy, the study provides a largely structuralist analysis of the emergent health context of the HGP. This perspective, which embraces an insightful nexus drawn from the literature on biomedicine, globalisation and the HGP, offers much utility by which to explore the basis of biomedical dominance, in particular, whether it is biomedicine’s links to the capitalist infrastructure, or its inherent efficacy and efficiency, that sustains the biomedical paradigm over “other” or non-biomedical health approaches. -

Ba3444 MAMMAL BOOKLET FINAL.Indd

Intot Obliv i The disappearing native mammals of northern Australia Compiled by James Fitzsimons Sarah Legge Barry Traill John Woinarski Into Oblivion? The disappearing native mammals of northern Australia 1 SUMMARY Since European settlement, the deepest loss of Australian biodiversity has been the spate of extinctions of endemic mammals. Historically, these losses occurred mostly in inland and in temperate parts of the country, and largely between 1890 and 1950. A new wave of extinctions is now threatening Australian mammals, this time in northern Australia. Many mammal species are in sharp decline across the north, even in extensive natural areas managed primarily for conservation. The main evidence of this decline comes consistently from two contrasting sources: robust scientifi c monitoring programs and more broad-scale Indigenous knowledge. The main drivers of the mammal decline in northern Australia include inappropriate fi re regimes (too much fi re) and predation by feral cats. Cane Toads are also implicated, particularly to the recent catastrophic decline of the Northern Quoll. Furthermore, some impacts are due to vegetation changes associated with the pastoral industry. Disease could also be a factor, but to date there is little evidence for or against it. Based on current trends, many native mammals will become extinct in northern Australia in the next 10-20 years, and even the largest and most iconic national parks in northern Australia will lose native mammal species. This problem needs to be solved. The fi rst step towards a solution is to recognise the problem, and this publication seeks to alert the Australian community and decision makers to this urgent issue. -

The Winston Churchill Memorial Trust of Australia

THE WINSTON CHURCHILL MEMORIAL TRUST OF AUSTRALIA 2015 Churchill Fellowship Report by Ms Bronnie Mackintosh PROJECT: This Churchill Fellowship was to research the recruitment strategies used by overseas fire agencies to increase their numbers of female and ethnically diverse firefighters. The study focuses on the three most widely adopted recruitment strategies: quotas, targeted recruitment and social change programs. DISCLAIMER I understand that the Churchill Trust may publish this report, either in hard copy or on the internet, or both, and consent to such publication. I indemnify the Churchill Trust against loss, costs or damages it may suffer arising out of any claim or proceedings made against the Trust in respect for arising out of the publication of any report submitted to the Trust and which the Trust places on a website for access over the internet. I also warrant that my Final Report is original and does not infringe on copyright of any person, or contain anything which is, or the incorporation of which into the Final Report is, actionable for defamation, a breach of any privacy law or obligation, breach of confidence, contempt of court, passing-off or contravention of any other private right or of any law. Date: 16th April 2017 1 | P a g e Winston Churchill Fellowship Report 2015. Bronnie Mackintosh. Table of Contents INTRODUCTION 3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 4 PROGRAMME 6 JAPAN 9 HONG KONG 17 INDIA 21 UNITED KINGDOM 30 STAFFORDSHIRE 40 CAMBRIDGE 43 FRANCE 44 SWEDEN 46 CANADA 47 LONDON, ONTARIO 47 MONTREAL, QUEBEC 50 UNITED STATES OF AMERICA 52 NEW YORK CITY 52 GIRLS FIRE CAMPS 62 LOS ANGELES 66 SAN FRANCISCO 69 ATLANTA 71 CONCLUSIONS 72 RECOMMENDATIONS 73 IMPLEMENTATION AND DISSEMINATION 74 2 | P a g e Winston Churchill Fellowship Report 2015. -

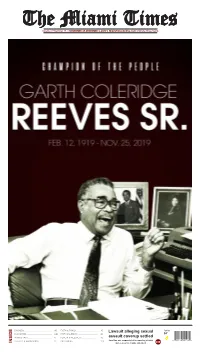

INSIDE and Coerced to Change Statement 10D Editorials Cartoons Opinions Letters

Volume 97 Number 15 | NOVEMBER 27-DECEMBER 3, 2019 | MiamiTimesOnline.com | Ninety-Three Cents BUSINESS ................................................. 8B FAITH & FAMILY ...................................... 7D Lawsuit alleging sexual Today CLASSIFIED ............................................. 11B FAITH CALENDAR ................................... 8D 84° IN GOOD TASTE ......................................... 1C HEALTH & WELLNESS ............................. 9D assault coverup settled LIFESTYLE HAPPENINGS ....................... 5C OBITUARIES ............................................. 12D Jane Doe was suspended after reporting attacks 8 90158 00100 0 INSIDE and coerced to change statement 10D Editorials Cartoons Opinions Letters VIEWPOINT BLACKS MUST CONTROL THEIR OWN DESTINY | NOVEMBER 27-DECEMBER 3, 2019 | MiamiTimesOnline.com MEMBER: National Newspaper Periodicals Postage Credo Of The Black Press Publisher Association paid at Miami, Florida Four Florida outrages: (ISSN 0739-0319) The Black Press believes that America MEMBER: The Newspaper POSTMASTER: Published Weekly at 900 NW 54th Street, can best lead the world from racial and Association of America Send address changes to Miami, Florida 33127-1818 national antagonism when it accords Subscription Rates: One Year THE MIAMI TIMES, The wealthy flourish, Post Office Box 270200 to every person, regardless of race, $65.00 – Two Year $120.00 P.O. Box 270200 Buena Vista Station, Miami, Florida 33127 creed or color, his or her human and Foreign $75.00 Buena Vista Station, Miami, FL Phone 305-694-6210 legal rights. Hating no person, fearing 7 percent sales tax for Florida residents 33127-0200 • 305-694-6210 the poor die H.E. SIGISMUND REEVES Founder, 1923-1968 no person, the Black Press strives to GARTH C. REEVES JR. Editor, 1972-1982 help every person in the firm belief that ith President Trump’s impeachment hearing domi- GARTH C. REEVES SR. -

Blessed Sacrament

Blessed Sacrament June 21, 2020 Roman Catholic Parish Blessed Sacrament Parish Directory Roman Catholic Parish 11300 North 64th Street, Scottsdale, AZ 85254 Clergy Phone: 480-948-8370 | Fax: 480-951-3844 Rev. Bryan Buenger, Parochial Administrator [email protected] | www.bscaz.org Rev. George Jingwa, Parochial Vicar Facebook: @BSScottsdale Rev. George Schroeder, Retired Deacon Jeff Strom Mass Times Senior Deacon Bob Evans Senior Deacon Jim Nazzal Bishop Olmsted has dispensed all of the faithful from the obligation to attend Sunday Mass until Administration further notice. Catholics are encouraged to make Mary Ann Bateman, Office Manager & SET Coordinator a Spiritual Communion, to pray the Rosary and Larry Cordier, Finance Manager other devotional prayers during this time. Lucille Franks, Coordinator of Parish Events Reconciliation Farah Olsen, Administrative Assistant Anne Roettger, Parish Secretary Wednesday @ 4pm Mary Ann Miller, Office Assistant Saturday @ 8:30am Liturgy Other Contact Information Mike Barta, Director of Liturgy & Music Julie McBride, Facilitator of Liturgy Preschool & Kindergarten Formation 480-998-9466 Dr. Larry Fraher, Director of Faith Formation Dr. Isabella Rice, Coordinator of Elementary RE Infant Baptism Jeremy Stafford, Coordinator of Youth Ministry Larry Fraher: ext. 216 Outreach Funeral Planning Mary Ellen Brown, Director of Engagement Julie McBride: ext. 208 Communications Sacrament Preparation Michelle Harvey, Director of Marketing & Media Larry Fraher: ext. 216 Maintenance Adults Returning to the Faith John Escajeda, Facilities Maintenance Manager Larry Fraher: ext. 216 Greg McBride, Maintenance Parish Representation John Carcanaques, Maintenance Pastoral Council President Preschool & Kindergarten Scott Bushey Heather Fraher, School Director Finance Council President Dan Mahoney Gift Shop is closed until further notice © 2020 Blessed Sacrament Roman Catholic Parish Ernest Shackleton set out on an expedition to make the first land crossing of the Antarctic continent. -

Zoogeography of the Land and Fresh-Water Mollusca of the New Hebrides"

Web Moving Images Texts Audio Software Patron Info About IA Projects Home American Libraries | Canadian Libraries | Universal Library | Community Texts | Project Gutenberg | Children's Library | Biodiversity Heritage Library | Additional Collections Search: Texts Advanced Search Anonymous User (login or join us) Upload See other formats Full text of "Zoogeography of the land and fresh-water mollusca of the New Hebrides" LI E) RARY OF THE UNIVLRSITY Of ILLINOIS 590.5 FI V.43 cop. 3 NATURAL ri'^^OHY SURVEY. Zoogeography of the LAND AND FRESH-WATER MOLLUSCA OF THE New Hebrides ALAN SOLEM Curator, Division of Lower Invertebrates FIELDIANA: ZOOLOGY VOLUME 43, NUMBER 2 Published by CHICAGO NATURAL HISTORY MUSEUM OCTOBER 19, 1959 Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 59-13761t PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA BY CHICAGO NATURAL HISTORY MUSEUM PRESS CONTENTS PAGE List of Illustrations 243 Introduction 245 Geology and Zoogeography 247 Phylogeny of the Land Snails 249 Age of the Land Mollusca 254 Land Snail Faunas of the Pacific Ocean Area 264 Land Snail Regions of the Indo-Pacific Area 305 converted by Web2PDFConvert.com Origin of the New Hebridean Fauna 311 Discussion 329 Conclusions 331 References 334 241 LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS TEXT FIGURES PAGE 9. Proportionate representation of land snail orders in different faunas. ... 250 10. Phylogeny of land Mollusca 252 11. Phylogeny of Stylommatophora 253 12. Range of Streptaxidae, Corillidae, Caryodidae, Partulidae, and Assi- mineidae 266 13. Range of Punctinae, "Flammulinidae," and Tornatellinidae 267 14. Range of Clausiliidae, Pupinidae, and Helicinidae 268 15. Range of Bulimulidae, large Helicarionidae, and Microcystinae 269 16. Range of endemic Enidae, Cyclophoridae, Poteriidae, Achatinellidae and Amastridae 270 17. -

07 Arruda & Thomé.Indd

ISSN 1517-6770 Recharacterization of the pallial cavity of Succineidae (Mollusca, Gastropoda) Janine Oliveira Arruda1 & José Willibaldo Thomé2 1Laboratório de Malacologia, Museu de Ciências e Tecnologia da Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Rio Grande do Sul, Avenida Ipiranga 6681, prédio 40, Bairro Partenon, Porto Alegre, RS, Brazil, ZIP:90619-900. E-mail: [email protected] 2Livre docente em Zoologia e professor titular aposentado da PUCRS. E-mail: [email protected] Abstract. The pallial cavity in the Succineidae family is characterized as Heterurethra. There, the primary ureter initiates at the kidney, near the pericardium, and runs transversely until the rectum. The secondary ureter travels a short distance along with the rectum. Then, it borders the mantle edge, passes the pneumostome and follows to the anterior region of the pallial cavity. The secondary ureter, then, folds in an 180o angle and becomes the tertiary ureter. It follows on the direction of the pneumostome and opens immediately before the respiratory orifice, on its right side, by the excretory pore. Key words. Omalonyx, Succinea, Heterurethra Resumo. Recaracterização da cavidade palial de Succineidae (Mollusca, Gastropoda). A cavidade palial na família Succineidae é caracterizada como Heterurethra. Neste, o ureter primário inicia-se no rim próximo ao pericárdio e corre transversalmente até o reto. O ureter secundário percorre uma pequena distância junto ao reto. Em seguida, este margeia a borda do manto, passa do pneumostômio e segue adiante até a região anterior da cavidade palial. O ureter secundário, então, se dobra em um ângulo de 180o e passa a ser denominado ureter terciário. Este se encaminha na direção do pneumostômio e se abre imediatamente anterior ao orifício respiratório, no lado direito deste, pelo poro excretor.