Frequently Ask Questions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Power of States and Business: Explaining

Ref. Ares(2017)5230581 - 26/10/2017 The power of states and business: Explaining transformative change in the fight against tax evasion and avoidance The Power of States and Business v2.0 19 September 2017 Document Details Work Package WP3 Lead Beneficiary University of Bamberg Deliverable ID D3.2 Date 05, 03, 2017 Submission 07, 28, 2017 Dissemination Level PU – Public / CO – Confidential / CI – Classified Information Version 1.0 Author(s) Lukas Hakelberg University of Bamberg Political Science [email protected] Acknowledgements The project “Combatting Fiscal Fraud and Empowering Regulators (COFFERS)” has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement No 727145. Document History Date Author Description 03-05-2017 Lukas Hakelberg First draft 19-09-2017 Lukas Hakelberg Second draft Page 2 of 52 The Power of States and Business v2.0 19 September 2017 Contents Document Details 2 Acknowledgements 2 Document History 2 Contents 3 Executive Summary 4 1. Introduction 5 2. Power in International Tax Policy 7 3. Post-Crisis Initiatives Against Tax Evasion and Avoidance 15 3.1 The Emergence of Multilateral AEI 16 3.1.1 Points of Departure: Savings Directive and Qualified Intermediary Program 16 3.1.2 Setting the Agenda: Left-of-Center Politicians and Major Tax Evasion Scandals 17 3.1.3 Towards New Rules: Legislative Initiatives in Europe and the US 20 3.1.4 The Role of Domestic Interest Groups: Tax Evaders and Financial Institutions 22 3.1.5 Reaching International Agreement: From Bilateral FATCA Deals to Multilateral AEI 25 3.2 Incremental Change in the Fight against Base Erosion and Profit Shifting 28 3.2.1 Points of Departure: Limiting Taxation at Source Through Transfer Pricing 28 3.2.2 Setting the Agenda: Starbuck’s and the Inclusion of Emerging Economies 30 3.2.3 Towards New Rules: The BEPS Report’s Ambiguous Recommendations 32 3.2.4 The Role of Interest Groups: In Defense of the Arm’s Length Principle 33 3.2.5 Reaching International Agreement? Ongoing EU-US Bargaining over BEPS 36 4. -

Narrative Report on Ireland

Financial Secrecy Index Ireland Narrative Report on Ireland Ireland is ranked at 47th position on the 2013 Financial Secrecy Index. This ranking is based on a combination of its Chart 1 - How Secretive? Moderately secrecy score and a scale weighting based on its share of the secretive 31-40 global market for offshore financial services. 41-50 Ireland has been assessed with 37 secrecy points out of a 51-60 potential 100, which places it into the moderately secretive 61-70 category at the bottom of the secrecy scale (see chart 1). 71-80 Ireland accounts for over 2 per cent of the global market for 81-90 offshore financial services, making it a small player compared with other secrecy jurisdictions (see chart 2). Exceptionally secretive 91-100 Part 1: Telling the story1 Chart 2 - How Big? Ireland as a financial centre: history and background Overview huge Ireland’s role as a secrecy jurisdiction or tax haven is based on two broad developments. The first, dating from 1956, is a regime of low tax rates and tax loopholes that have large encouraged transnational businesses to relocate – often small only on paper – to Ireland. The second is the role of the tiny Dublin-based International Financial Services Centre (IFSC), a Wild-West, deregulated financial zone set up in 1987 under the corrupt Irish politician Charles Haughey, which has striven particularly to host international ‘shadow banking’ activity2. Ireland’s secrecy score of 37 makes it one of the least secretive jurisdictions on our index: secrecy was never a central part of its ‘offshore’ offering. -

The Financial Secrecy Index: Shedding New Light on the Geography of Secrecy

The Financial Secrecy Index: Shedding New Light on the Geography of Secrecy Alex Cobham, Petr Janský, and Markus Meinzer Abstract Both academic research and public policy debate around tax havens and offshore finance typically suffer from a lack of definitional consistency. Unsurprisingly then, there is little agreement about which jurisdictions ought to be considered as tax havens—or which policy measures would result in their not being so considered. In this article we explore and make operational an alternative concept, that of a secrecy jurisdiction and present the findings of the resulting Financial Secrecy Index (FSI). The FSI ranks countries and jurisdictions according to their contribution to opacity in global financial flows, revealing a quite different geography of financial secrecy from the image of small island tax havens that may still dominate popular perceptions and some of the literature on offshore finance. Some major (secrecy-supplying) economies now come into focus. Instead of a binary division between tax havens and others, the results show a secrecy spectrum, on which all jurisdictions can be situated, and that adjustment lfor the scale of business is necessary in order to compare impact propensity. This approach has the potential to support more precise and granular research findings and policy recommendations. JEL Codes: F36, F65 Working Paper 404 www.cgdev.org May 2015 The Financial Secrecy Index: Shedding New Light on the Geography of Secrecy Alex Cobham Tax Justice Network Petr Janský Institute of Economic Studies, Faculty of Social Sciences, Charles University in Prague Markus Meinzer Tax Justice Network A version of this paper is published in Economic Geography (July 2015). -

The Relationship Between MNE Tax Haven Use and FDI Into Developing Economies Characterized by Capital Flight

1 The relationship between MNE tax haven use and FDI into developing economies characterized by capital flight By Ali Ahmed, Chris Jones and Yama Temouri* The use of tax havens by multinationals is a pervasive activity in international business. However, we know little about the complementary relationship between tax haven use and foreign direct investment (FDI) in the developing world. Drawing on internalization theory, we develop a conceptual framework that explores this relationship and allows us to contribute to the literature on the determinants of tax haven use by developed-country multinationals. Using a large, firm-level data set, we test the model and find a strong positive association between tax haven use and FDI into countries characterized by low economic development and extreme levels of capital flight. This paper contributes to the literature by adding an important dimension to our understanding of the motives for which MNEs invest in tax havens and has important policy implications at both the domestic and the international level. Keywords: capital flight, economic development, institutions, tax havens, wealth extraction 1. Introduction Multinational enterprises (MNEs) from the developed world own different types of subsidiaries in increasingly complex networks across the globe. Some of the foreign host locations are characterized by light-touch regulation and secrecy, as well as low tax rates on financial capital. These so-called tax havens have received widespread media attention in recent years. In this paper, we explore the relationship between tax haven use and foreign direct investment (FDI) in developing countries, which are often characterized by weak institutions, market imperfections and a propensity for significant capital flight. -

8 May 2018 Tax Justice Network Response to the Questionnaire of The

8 May 2018 Tax Justice Network response to the questionnaire of the European Parliament Special Committee on Tax Crimes, Tax Evasion and Tax Avoidance ("TAX3"), in advance of the hearing on "The fight against harmful tax practices within the European Union and abroad", scheduled for 15 May 2018: Why the TJN FSI lists 41 jurisdictions and the EU lists 9 jurisdictions at the moment? What differences in methodology do you notice? Could you explain the criteria used for the construction of the Financial Secrecy Index (FSI)? How could FSI be used for the implementation of anti-tax avoidance and even anti-money laundering rules in the EU and in the rest of the world? * The Tax Justice Network welcomes the opportunity to provide evidence to the European Parliament Special Committee on Tax Crimes, Tax Evasion and Tax Avoidance ("TAX3"), and the energy which is now dedicated to addressing the major issues of international tax abuse which have been revealed by the Panama Papers, Paradise Papers, LuxLeaks and in a range of other investigative work and by our own research. For example, using a methodology developed by researchers at the International Monetary Fund, we estimate that global revenue losses to the profit shifting of multinational companies is in the order of $500 billion a year – and disproportionately felt by lower-income countries where those revenues are most badly needed. At the same time, EU member states are included among the biggest losers – and also among the most aggressive in seeking to disadvantage their neighbours. A similar pattern holds in respect of offshore tax evasion. -

Narrative Report on Panama

NARRATIVE REPORT ON PANAMA PART 1: NARRATIVE REPORT Rank: 15 of 133 Panama ranks 15th in the 2020 Financial Secrecy Index, with a high secrecy score of 72 but a small global scale weighting (0.22 per cent). How Secretive? 72 Coming within the top twenty ranking, Panama remains a jurisdiction of particular concern. Overview and background Moderately secretive 0 to 25 Long the recipient of drugs money from Latin America and with ample other sources of dirty money from the US and elsewhere, Panama is one of the oldest and best-known tax havens in the Americas. In recent years it has adopted a hard-line position as a jurisdiction that refuses to 25 to 50 cooperate with international transparency initiatives. In April 2016, in the biggest leak ever, 11.5 million documents from the Panama law firm Mossack Fonseca revealed the extent of Panama’s involvement in the secrecy business. The Panama Papers showed the 50 to 75 world what a few observers had long been saying: that the secrecy available in Panama makes it one of the world’s top money-laundering locations.1 Exceptionally 75 to 100 In The Sink, a book about tax havens, a US customs official is quoted as secretive saying: “The country is filled with dishonest lawyers, dishonest bankers, dishonest company formation agents and dishonest How big? 0.22% companies registered there by those dishonest lawyers so that they can deposit dirty money into their dishonest banks. The Free Trade Zone is the black hole through which Panama has become one of the filthiest money laundering sinks in the huge world.”2 Panama has over 350,000 secretive International Business Companies (IBCs) registered: the third largest number in the world after Hong Kong3 and the British Virgin Islands (BVI).4 Alongside incorporation of large IBCs, Panama is active in forming tax-evading foundations and trusts, insurance, and boat and shipping registration. -

Taking Stock

Netzwerk Women in Development Europe Taking Stock The financial crisis and development from a feminist perspective WIDE’s Position paper on the global social, economic and environmental crisis Rue Hobbema 59 1000 Brussels Belgium Tel: +32 2 545 90 70 Fax: +32 2 512 73 42 [email protected] www.wide-network.org Authors Ursula Dullnig, Brita Neuhold, Traude Novy, Kathrin Pelzer, Edith Schnitzer, Barbara Schöllenberger, Claudia Thallmayer Editing Gerhild Perlaki-Straub, Hannah Golda This paper has been produced with the financial assistance of AECID, the European Union and HIVOS. The contents of the paper are the sole responsibility of WIDE and can under no circumstances be regarded as reflecting the position of the Funders. Publisher WIDE – Netzwerk Women in Development Europe Währingerstr. 2-4/22 1090 Vienna, Austria Tel: (+43-1) 317 40 31, E-Mail: [email protected] http://www.wide-netzwerk.at Central Register number: 626905553 Copyright © January 2010 WIDE Any parts of this publication may be reproduced without the permission for educational and non- profit purposes if the source is acknowledged. WIDE would appreciate a copy of the text in which document is used or cited. 2 CONTENTS 1. WHY THIS FEMALE-ORIENTED PUBLICATION IS NECESSARY..................................................... 4 2. HIGHLIGHTS ON THE BACKDROP TO THE FINANCIAL CRISIS ..................................................... 7 3. THE PROTECTIVE SHIELD FOR THE FINANCIAL SECTOR AND ITS EFFECTS ON WOMEN ......... 11 4. FACTS AND FIGURES ABOUT THE FINANCIAL AND ECONOMIC CRISIS SINCE 2008 ................ 13 5. REVIEW: THE MEXICAN AND ASIAN FINANCIAL CRISES .......................................................... 18 6. WHO IS PAYING FOR THE CRISIS? ............................................................................................ 21 7. MEASURES AT THE INTERNATIONAL LEVEL ........................................................................... -

Mapping Financial Centres

Helpdesk Report Mapping Financial Centres Hannah Timmis Institute of Development Studies 15 May 2018 Question What are the key financial centres that affect developing countries? Contents 1. Overview 2. IFCs and developing countries 3. Key IFCs 4. References The K4D helpdesk service provides brief summaries of current research, evidence, and lessons learned. Helpdesk reports are not rigorous or systematic reviews; they are intended to provide an introduction to the most important evidence related to a research question. They draw on a rapid desk- based review of published literature and consultation with subject specialists. Helpdesk reports are commissioned by the UK Department for International Development and other Government departments, but the views and opinions expressed do not necessarily reflect those of DFID, the UK Government, K4D or any other contributing organisation. For further information, please contact [email protected]. 1. Overview International financial centres (IFCs) are characterised by favourable tax regimes for foreign corporations. They are theorised to affect developing countries in three key ways. First, they divert real and financial flows away from developing countries. Second, they erode developing countries’ tax bases and thus public resources. Third, IFCs can affect developing countries’ own tax policies by motivating governments to engage in tax competition. The form and scale of these effects across different countries depend on complex interactions between their national tax policies and those of IFCs. In order to better understand the relationship between national tax regimes and development, in 2006, the IMF, OECD, UN and World Bank recommended to the G-20 that all members undertake “spillover analyses” to assess the impact of their tax policies on developing countries. -

Survival of the Richest. Europe's Role in Supporting an Unjust Global Tax

Survival of the Richest Europe’s role in supporting an unjust global tax system 2016 Acknowledgements This report was produced by civil society organisations in countries across Europe, including: Attac Austria (Austria); Vienna Institute for International Dialogue and Cooperation (VIDC) (Austria); 11.11.11 (Belgium); Centre national de coopération au développement (CNCD-11.11.11) (Belgium); Glopolis (Czech Republic); Oxfam IBIS (Denmark); Kehitysyhteistyön palvelukeskus (KEPA) (Finland); CCFD-Terre Solidaire (France); Oxfam France (France); Netzwerk Steuergerechtigkeit (Germany); Debt and Development Coalition Ireland (DDCI) (Ireland); Oxfam Italy (Italy); Re:Common (Italy); Latvijas platforma attīstības sadarbībai (Lapas) (Latvia); Collectif Tax Justice Lëtzebuerg (Luxembourg); the Centre for Research on Multinational Corporations (SOMO) (Netherlands); Tax Justice Netherlands (Netherlands); Tax Justice Network Norway (Norway); Instytut Globalnej Odpowiedzialnosci (IGO) (Poland); Ekvilib Institute (Slovenia); Focus Association for Sustainable Development (Slovenia); Inspiraction (Spain); Forum Syd (Sweden); Christian Aid (UK). The overall report was coordinated by Eurodad. Each national chapter was written by – and is the responsibility of – the nationally-based partners in the project. The views in each chapter do not reflect the views of the rest of the project partners. The chapters on Luxembourg and Spain were written by – and are the responsibility of – Eurodad. Design and artwork: James Adams. Copy editing: Vicky Anning, Jill McArdle and Julia Ravenscroft. The authors believe that all of the details of this report are factually accurate as of 15 November 2016. This report has been produced with the financial assistance of the European Union, the Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation (Norad) and Open Society Foundations. The contents of this publication are the sole responsibility of Eurodad and the authors of the report, and can in no way be taken to reflect the views of the funders. -

Stellungnahme Des Netzwerks Für Steuergerechtigkeit (Tax Justice

Nicola Liebert, Tax Justice Network Mitglied im europäischen Lenkungsausschuss www.taxjustice.net Berlin, d. 2.7.2010 Stellungnahme des Netzwerks für Steuergerechtigkeit (Tax Justice Network) zur öffentlichen Anhörung des Finanzausschusses des Deutschen Bundestags zur Frage der Bekämpfung der Steuerhin- terziehung am 7. Juli 2010 1. Die beinahe leeren Schwarzen und Grauen Listen der OECD Im April 2009 veröffentlichte die OECD auf Aufforderung der G20 hin eine neue Schwarze, eine Graue und eine Weiße Liste überwachter Staaten und Gebiete. Auf der Schwarzen Lis- te fanden sich zur Überraschung selbst von Kennern der Materie lediglich vier Staaten – Costa Rica, Malaysia, die Philippinen und Uruguay – und das auch nur fünf Tage lang. Dann teilte OECD-Generalsekretär Angel Gurría mit, dass sich alle vier Staaten künftig an den OECD-Standard über den Informationsaustausch mit den Steuerbehörden anderer Länder halten wollten, was ausreichte, um von der Schwarzen Liste genommen zu werden. Auch die Graue Liste derer, die den OECD-Standard akzeptiert, aber noch nicht in ausrei- chender Form umgesetzt haben, wird immer kürzer. Sie umfasste am 23.6.2010 noch 14 Länder, darunter Costa Rica, die Philippinen und Uruguay, die von der ursprünglichen schwarzen Liste aufgestiegen waren, sowie im globalen Maßstab unbedeutende Steueroa- sen wie Montserrat, Nauru, Niue und Vanuatu. Um auf der Weißen Liste geführt zu werden, ist der Abschluss von nur zwölf bilateralen Informationsaustauschabkommen hinreichend. Zu den Ländern, mit denen so zum Beispiel Liechtenstein Abkommen geschlossen hat, gehören neben Deutschland und Großbritannien auch Andorra und Monaco. Insgesamt hat die Zahl der Abkommen zwischen Staaten der Grauen Liste sprunghaft zugenommen, was nichts anderes bedeutet, als dass sich die Steueroasen gegenseitig den Status als „kooperative“ Staaten bzw. -

The Financial Secrecy Index Vs Tax Haven Lists

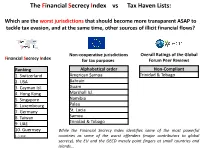

The Financial Secrecy Index vs Tax Haven Lists: Which are the worst jurisdictions that should become more transparent ASAP to tackle tax evasion, and at the same time, other sources of illicit financial flows? Non-cooperative jurisdictions Overall Ratings of the Global Financial Secrecy Index for tax purposes Forum Peer Reviews Ranking Alphabetical order Non-Compliant 1. Switzerland American Samoa Trinidad & Tobago 2. USA Bahrain 3. Cayman Isl. Guam 4. Hong Kong Marshall Isl. 5. Singapore Namibia 6. Luxembourg Palau 7. Germany St. Lucia 8. Taiwan Samoa 9. UAE Trinidad & Tobago 10. Guernsey While the Financial Secrecy Index identifies some of the most powerful (…) 112. countries as some of the worst offenders (major contributors to global secrecy), the EU and the OECD merely point fingers at small countries and islands… Financial Secrecy Non-cooperative Overall Index jurisdictions Ratings Number of jurisidctions considered not 1 (NC) & 7 112* 9 transparent / cooperative enough? (PC)** Average Secrecy Score of the worst 69.61 74.37*** 65.25 jurisdictions? [Top 10 jurisdictions only] [NC only] [0 = Transparency; 100 = Full Secrecy] Offshore Financial Services (FSI’s Global 58% [Top 10 jurisdictions only] 0.15%*** 0.0001% Scale Weight) of the worst jurisdictions? [NC only] [100% = all market share of offshore financial services] FSI Share (% of financial secrecy for which 32% [Top 10 jurisdictions only] 2.94%*** 0.09% the worst jurisdictions are responsable) [NC only] [100% = responsible for all of the world’s financial secrecy] * None of the 112 jurisdiction reaches at least 60% of transparency (no jurisdiction has a Secrecy Score equal to or below 40%). -

Basel AML Index 2019 a Country Ranking and Review of Money Laundering and Terrorist Financing Risks Around the World

Basel AML Index 2019 A country ranking and review of money laundering and terrorist financing risks around the world International Centre for Asset Recovery | August 2019 Basel Institute on Governance Steinenring 60 | 4051 Basel, Switzerland | +41 61 205 55 11 [email protected] | www.baselgovernance.org BASEL INSTITUTE ON GOVERNANCE Table of contents 1 Introduction 1 2 What does the Basel AML Index measure? 1 3 Scores and ranking 4 4 Analysis of results 6 5 Comparison of countries across five domains 12 6 Special indicator focus - analysis of FATF data 19 7 Special regional focus – post-Soviet countries 22 8 Looking ahead 24 9 Subscription details 25 10 About and contact 26 11 Annex I: Methodology 27 12 Annex II: Indicators 32 Table of tables Table 1: Basel AML Index 2019 - Public Edition .................................................................................... 6 Table 2: Top 5 improving countries ..................................................................................................... 11 Table 3: Top 5 deteriorating countries ................................................................................................ 12 Table 4: Top performing countries in Domain 1 ................................................................................... 13 Table 5: Top performing countries in Domain 1 with an FATF fourth-round evaluation .......................... 14 Table 6: Lowest performing countries in Domain 1 ............................................................................. 14 Table 7: Top