This Is “Newspapers”, Chapter 4 from the Book Mass Communication, Media, and Culture (Index.Html) (V. 1.0). This Book Is

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Entertainment & Syndication Fitch Group Hearst Health Hearst Television Magazines Newspapers Ventures Real Estate & O

hearst properties WPBF-TV, West Palm Beach, FL SPAIN Friendswood Journal (TX) WYFF-TV, Greenville/Spartanburg, SC Hardin County News (TX) entertainment Hearst España, S.L. KOCO-TV, Oklahoma City, OK Herald Review (MI) & syndication WVTM-TV, Birmingham, AL Humble Observer (TX) WGAL-TV, Lancaster/Harrisburg, PA SWITZERLAND Jasper Newsboy (TX) CABLE TELEVISION NETWORKS & SERVICES KOAT-TV, Albuquerque, NM Hearst Digital SA Kingwood Observer (TX) WXII-TV, Greensboro/High Point/ La Voz de Houston (TX) A+E Networks Winston-Salem, NC TAIWAN Lake Houston Observer (TX) (including A&E, HISTORY, Lifetime, LMN WCWG-TV, Greensboro/High Point/ Local First (NY) & FYI—50% owned by Hearst) Winston-Salem, NC Hearst Magazines Taiwan Local Values (NY) Canal Cosmopolitan Iberia, S.L. WLKY-TV, Louisville, KY Magnolia Potpourri (TX) Cosmopolitan Television WDSU-TV, New Orleans, LA UNITED KINGDOM Memorial Examiner (TX) Canada Company KCCI-TV, Des Moines, IA Handbag.com Limited Milford-Orange Bulletin (CT) (46% owned by Hearst) KETV, Omaha, NE Muleshoe Journal (TX) ESPN, Inc. Hearst UK Limited WMTW-TV, Portland/Auburn, ME The National Magazine Company Limited New Canaan Advertiser (CT) (20% owned by Hearst) WPXT-TV, Portland/Auburn, ME New Canaan News (CT) VICE Media WJCL-TV, Savannah, GA News Advocate (TX) HEARST MAGAZINES UK (A+E Networks is a 17.8% investor in VICE) WAPT-TV, Jackson, MS Northeast Herald (TX) VICELAND WPTZ-TV, Burlington, VT/Plattsburgh, NY Best Pasadena Citizen (TX) (A+E Networks is a 50.1% investor in VICELAND) WNNE-TV, Burlington, VT/Plattsburgh, -

Measuring the Effects of Interpretive Journalism on Trust and Credibility Perceptions in the Context of Political News Coverage

Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports 2019 Measuring the Effects of Interpretive Journalism on Trust and Credibility Perceptions in the Context of Political News Coverage Scott William Siker West Virginia University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd Part of the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Siker, Scott William, "Measuring the Effects of Interpretive Journalism on Trust and Credibility Perceptions in the Context of Political News Coverage" (2019). Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports. 4098. https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd/4098 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by the The Research Repository @ WVU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you must obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in WVU Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports collection by an authorized administrator of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports 2019 Measuring the Effects of Interpretive Journalism on Trust and Credibility Perceptions in the Context of Political News Coverage Scott iW lliam Siker Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd Part of the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Measuring the Effects of Interpretive Journalism on Trust and Credibility Perceptions in the Context of Political News Coverage Scott Siker Thesis submitted to the Reed College of Media at West Virginia University In partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Master of Science in Journalism Geah Pressgrove, Ph.D., Chair Julia Fraustino, Ph.D. -

HEARST PROPERTIES HUNGARY HEARST MAGAZINES UK Hearst Central Kft

HEARST PROPERTIES HUNGARY HEARST MAGAZINES UK Hearst Central Kft. (50% owned by Hearst) All About Soap ITALY Best Cosmopolitan NEWSPAPERS MAGAZINES Hearst Magazines Italia S.p.A. Country Living Albany Times Union (NY) H.M.C. Italia S.r.l. (49% owned by Hearst) Car and Driver ELLE Beaumont Enterprise (TX) Cosmopolitan JAPAN ELLE Decoration Connecticut Post (CT) Country Living Hearst Fujingaho Co., Ltd. Esquire Edwardsville Intelligencer (IL) Dr. Oz THE GOOD LIFE Greenwich Time (CT) KOREA Good Housekeeping ELLE Houston Chronicle (TX) Hearst JoongAng Y.H. (49.9% owned by Hearst) Harper’s BAZAAR ELLE DECOR House Beautiful Huron Daily Tribune (MI) MEXICO Laredo Morning Times (TX) Esquire Inside Soap Hearst Expansion S. de R.L. de C.V. Midland Daily News (MI) Food Network Magazine Men’s Health (50.1% owned by Hearst UK) (51% owned by Hearst) Midland Reporter-Telegram (TX) Good Housekeeping Prima Plainview Daily Herald (TX) Harper’s BAZAAR NETHERLANDS Real People San Antonio Express-News (TX) HGTV Magazine Hearst Magazines Netherlands B.V. Red San Francisco Chronicle (CA) House Beautiful Reveal The Advocate, Stamford (CT) NIGERIA Marie Claire Runner’s World (50.1% owned by Hearst UK) The News-Times, Danbury (CT) HMI Africa, LLC O, The Oprah Magazine Town & Country WEBSITES Popular Mechanics NORWAY Triathlete’s World Seattlepi.com Redbook HMI Digital, LLC (50.1% owned by Hearst UK) Road & Track POLAND Women’s Health WEEKLY NEWSPAPERS Seventeen Advertiser North (NY) Hearst-Marquard Publishing Sp.z.o.o. (50.1% owned by Hearst UK) Town & Country Advertiser South (NY) (50% owned by Hearst) VERANDA MAGAZINE DISTRIBUTION Ballston Spa/Malta Pennysaver (NY) Woman’s Day RUSSIA Condé Nast and National Magazine Canyon News (TX) OOO “Fashion Press” (50% owned by Hearst) Distributors Ltd. -

Proceedings of the American Journalism Historians' Association Conference (Salt Lake City, Utah, October 5-7, 1993)

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 367 975 CS 214 204 TITLE Proceedings of the American Journalism Historians' Association Conference (Salt Lake City, Utah, October 5-7, 1993). Part I: Newspapers and Journalism. INSTITUTION American Journalism Historians' Association. PUB DATE Oct 93 NOTE 608p. PUB TYPE Collected Works - Conference Proceedings (021)-- Historical Materials (060) EDRS PRICE MF03/PC25 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Civil War (United States); Colonial History (United States); *Freedom of Speech; Health Education; Journalism Education; Journalism History; Libeland Slander; *Mass Media Role; *Newspapers; Peace; Periodicals; Reconstruction Era; *Sex Role; WorldWar II IDENTIFIERS Atomic Bomb; Canada; Chinese Revolution (1911); Journalists; *Media Coverage; Professional Concerns; Utah ABSTRACT The Newspapers and Journalism section of the proceedings of this conference of journalism historianscontains the following 22 papers: "'For Want of the Actual Necessariesof Life': Survival strategies of Frontier Journalists in theTrans-Mississippi West" (Larry Cebula); "'Legal Immunity forFree Speaking': Judge Thomas M. Cooley, 'The Det,oit Evening News,' and 'NewYork Times v. Sullivan'" (Richard Digby-Junger); "The Dilemma ofFemininity: Gender and Journalistic Professionalism in World War II" (Hei-lingYang); "'An American Conspiracy': The Post-WatergatePress and the CIA" (Kathryn S. Olmsted); "Female Arguments:An Examination of the Utah Woman's Suffrage Debates of 1880 ane. 1895as Represented in Utah Women's Newspapers" (Janika Isakson); "BackChannel: What Readers Learned of the 'Tri-City Herald's' Lobbying forthe Hanford Nuclear Reservation" (Thomas H. Hettterman); "The CanadianDragon Slayer: The Reform Press of Upper Canada" (Karla K. Gower); "TheCampaign for Libel Reform: State Press Associations in the Late1800s" (Tim Gleason); "Partisan News in theNineteenth-Century: Detroit's Dailies in the Reconstruction Era, 1865-1876" (RichardL. -

Rethinking Photojournalism the Changing Work Practices and Professionalism of Photojournalists in the Digital Age

10.2478/nor-2014-0017 Nordicom Review 35 (2014) 2, pp. 91-104 Rethinking Photojournalism The Changing Work Practices and Professionalism of Photojournalists in the Digital Age Jenni Mäenpää Abstract Public service, ethics, objectivity, autonomy and immediacy are still often considered the core values of professional journalism. However, photojournalistic work has confronted historic changes since the advent of digitalization in the late 1980s. Professional photo- journalists have been caught manipulating news images, video production has become a major part of news photographers’ work, and newspapers freely publish photographs and videos taken by the general public. The present article examines how news photographers negotiate these changes in photo- journalistic work practices, and how they define their professional ambitions in the digital age. Photojournalists’ articulations of professionalism are approached in relation to three digital innovations in photojournalism: digital photo editing, video production and user-generated images in newspapers. The empirical data consist of an online survey of and interviews with photojournalists in Finland. In the final analysis, it is suggested that the core ideals of photo- journalism have to be renegotiated, because the work environment has changed drastically. Keywords: photojournalism, news photographers, professionalism, digital photo editing, online news videos, amateur photography. Introduction In my opinion, a RAW file has nothing to do with reality, and I do not think you can judge the finished images and the use of Photoshop by looking at the RAW file. (Danish photojournalist Klavs Bo Christensen, April 13, 2009) This argument was made by a Danish photojournalist after he had been disqualified from a Picture of the Year contest because contest officials had determined that his im- age manipulation went too far. -

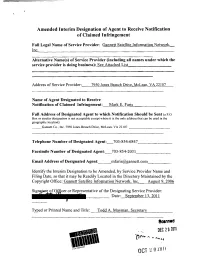

Amended Interim Designation of Agent to Receive Notification of Claimed Infringement

Amended Interim Designation of Agent to Receive Notification of Claimed Infringement Full Legal Name of Service Provider: Gannett Satellite Information Network, Alternative Name(s) of Service Provider (including all names under which the service provider is doing business):...::S:o..::e:....::e-=A-=.t=ta=.:c=h=ec...::;dc...::L=i=.st=-________ Address of Service Provider:_~..:....79"-'5:...!O:.....:J'-"o=n=es"-B=ra=n=ch=D=n:...:.·v-=.e,,,-,M=.=,.c=L=ea=nO>,.,-,V....:o..A.:..=c22::..:1"-,,Oc..:.,7__ Name of Agent Designated to Receive Notification of Claimed Infringement:_...;.M~a=rk",--,,=,E:!....""-.F=an,,-,"·::<..,s_______ Full Address of Designated Agent to which Notification Should be Sent (a P.O. Box or similar designation is not acceptable except where it is the only address that can be used in the geographic location): __Gannett Co., Inc. 7950 Jones Branch Drive, McLean, VA 22107 _________ Telephone Number of Designated Agent:_703-854-6847_______ Facsimile Number of Designated Agent:_703-854-203 Email AddressofDesignatedAgent: [email protected]_____ Identify the Interim Designation to be Amended, by Service Provider Name and Filing Date, so that it may be Readily Located in the Directory Maintained by the Copyright Office: Gannett Satellite Information Network, Inc. August 9, 2006 cer or Representative of the Designating Service Provider: ---__ Date: September 13, 2011 Typed or Printed Name and Title: _~T",-,o,,-,d=d::....:A:....:::-.M:..:.=a:.,.L.y=m=a=n,,-,=S.:;.;ec=r..::..et=a"'-.,ryl-....-_____ bnn.d DEC 201011 OCT i.! -

Climate Journalism and Its Changing Contribution to an Unsustainable Debate

Brüggemann, Michael (2017): Post-normal journalism: Climate journalism and its changing contribution to an unsustainable debate. In Peter Berglez, Ulrika Olausson, Mart Ots (Eds.): What is Sustainable Journalism? Integrating the Environmental, Social, and Economic Challenges of Journalism. New York: Peter Lang, pp. 57–73. [Final accepted manuscript] Chapter 4 Post-normal Journalism: Climate Journalism and Its Changing Contribution to an Unsustainable Debate Michael Brüggemann Introduction1 Deliberative public sphere theories ascribe an ‘epistemic dimension’ to public debates: they do not necessarily foster consensus, but rather an enhanced understanding among the participants of the debate through the exchange of opinions backed by justifications (Habermas 2006; Peters 2005). Public discourses provide a critical validation of issues of shared relevance. They are an important precondition for the sustainable evolution of society as a society without open debates becomes blind to the concerns of its citizens. This is why the sustainability of public debates is a major concern for society and for communication studies. Reality will always fall short of normative models of the public sphere (see e.g. Walter 2015), yet when issues become so polarized that an open debate among speakers from different backgrounds becomes impossible, this constitutes a problem for democracy. Particularly in the United States, the debate on climate change has joined other issues such as abortion and gun control as part of a wider cultural schism: “Extreme positions dominate the conversation, the potential for discussion or resolution disintegrates, and the issue becomes intractable” (Hoffman 2015, p. 6). This kind of situation emerges due to a multitude of factors. Returning to a more constructive debate requires broad and complex responses. -

PROBLEMS & ETHICS in JOURNALISM: JOU4700*05A5 Mondays: 3 – 6 P.M. Fall 2013

1 PROBLEMS & ETHICS IN JOURNALISM: JOU4700*05A5 Mondays: 3 – 6 p.m. Fall 2013: August 26 to Dec. 9, 2013 Turlington 2318 Professor: Daniel Axelrod Office Hours: By appointment Office: Weimer 2040 Cell: 978-855-8935. If your matter is time sensitive, feel free to call (but please don’t text me). Email: [email protected] SYLLABUS DISCLAIMER Sometimes, teachers say things that contradict the syllabus. To avoid confusion and ensure a clear, fair class, this syllabus is our ultimate authority. Simply put, if the syllabus contradicts something that I say in class, the syllabus wins unless I expressly and specifically state that I am intentionally revising it. In such cases, I will provide prompt, clear, and ample notification. COURSE OVERVIEW This “Problems and Ethics in Journalism” class is broken into three parts. First, this course covers the underlying principles of how to be an ethical journalist and the history behind them; then it discusses media literacy (how to recognize the strengths, weaknesses and biases in news coverage); and — with a particular focus on the business of journalism — the class concludes by explaining the challenges media outlets and journalists face when it comes to producing high- quality news in an ethical manner (E.g. the influence of advertisers, corporate owners, public relations specialists, and governments). 1. First, we outline the basics of journalism ethics to ensure you have a solid foundation. 2. Next, we cover “media literacy.” That means we’re going to make sure that you become an educated news consumer. After this unit, you’ll be able to look a news story (regardless of the platform on which appears) and rip it apart. -

Coddington-Dissertation-2015

Copyright by Mark Allen Coddington 2015 The Dissertation Committee for Mark Allen Coddington certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Telling Secondhand Stories: News Aggregation and the Production of Journalistic Knowledge Committee: Stephen D. Reese, Supervisor C. W. Anderson Mary Angela Bock Regina G. Lawrence Sharon L. Strover Telling Secondhand Stories: News Aggregation and the Production of Journalistic Knowledge by Mark Allen Coddington, B.A.; M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin August 2015 Dedication For Dana, whose patience, sacrifice, and grace made this project possible and inspire me daily. Acknowledgements This dissertation is not mine alone, but a product of the contributions of so many people who have guided and aided me throughout its progress, and through my development as a scholar more generally. I am deeply indebted and profoundly grateful for their encouragement, wisdom, and help. I alone bear responsibility for the shortcomings of this project, but they deserve credit for bringing it to fruition and for their rich contributions to my growth as a scholar and a person. I am grateful to have learned under a remarkably wise and supportive faculty at the University of Texas over the past five years, most notably my adviser, Stephen Reese. Dr. Reese has been an ideal supervisor for both my master’s thesis and dissertation, continually nudging me forward and honing my ideas while giving me space to grow as a thinker. -

Federal Monitor: DCF Reforms on Track, but Much More Must Be Done

Advertisements Weather | Jobs | Cars | Real Estate | Apartments | Shopping | Classifieds | PressPix | Calendar | EZClassif Back Issues: Wed | Thu | Fri | Sat | Sun | Mon | Tue | Today SEARCH THE JERSEY SHORE: « what is this? SPONSORED By Go Advertise E-mail Print Subscribe NJ Lottery 2ND ROUND REPORT JOB OPENINGS Work for Us Earn Federal monitor: DCF reforms on $800/mo. track, but much more must be done CONTESTS Reader Posted by the Asbury Park Press on 10/23/07 Rewards EDUCATION BY MICHAEL RISPOLI Newspaper in GANNETT STATE BUREAU Education Program MERCHANDISE Post Comment Newspaper Store TRENTON The state Department of Children and Families has been "focused and productive" in working to improve New Jersey's child welfare system during its second MARKETPLACE round of evaluation, said a federal monitor's report released Monday. Fishing & Boating The 71-page report, which measures the department's progress under a July 2006 Restaurants settlement reached between the state and Children Rights Inc., a New York child advocacy group, said the state "fulfilled and often exceeded the expectations" set by READERS' the agreement. CHOICE Best of 2006 "Many promising strategies have been introduced, which will need to be consistently translated into new practices and accessible services on the ground for the ADVERTISING department to succeed in its mission of fundamentally changing how it works with Advertising children and families in New Jersey," said the report, published by the Center for the Services Study of Social Policy, based in Washington. LISTINGS Judith Meltzer, the federal monitor who reviewed the agency, said that although there Vacation have been many accomplishments, "The state's child welfare system today does not Rentals consistently function well. -

Cultural Journalism - Journalism About Culture

Cultural Journalism - Journalism about Culture Kristensen, Nete Nørgaard Published in: Sociology Compass DOI: 10.1111/soc4.12701 Publication date: 2019 Document version Peer reviewed version Citation for published version (APA): Kristensen, N. N. (2019). Cultural Journalism - Journalism about Culture. Sociology Compass, 13(6), 1-13. [e12701]. https://doi.org/10.1111/soc4.12701 Download date: 30. Sep. 2021 Received: 12 November 2018 Revised: 26 February 2019 Accepted: 11 April 2019 DOI: 10.1111/soc4.12701 ARTICLE Cultural journalism—Journalism about culture Nete Nørgaard Kristensen Department of Media, Cognition and Communication, Section for Film, Media and Abstract Communication, University of Copenhagen This article is an introduction to “cultural journalism,”a Correspondence specialised type of professional journalism that covers and Nete Nørgaard Kristensen, Professor, PhD, debates the broad field of arts and culture. The article Department of Media, Cognition and Communication, Section for Film, Media and points to some of the research traditions that have engaged Communication, University of Copenhagen, with the news media's coverage of arts and culture and Karen Blixens Plads 8, 2300 Copenhagen S, Denmark. inspired contemporary cultural journalism research, among Email: [email protected] them cultural sociology and the sociology of journalism. Funding information Furthermore, the article outlines the institutional roles and Independent Research Fund Denmark, Grant/ epistemology of cultural journalism, which in several Award Number: DFF ‐ 4180‐00082. DFF – 4180‐00082 respects differ from dominating normative conceptions of Western journalism. At the same time, the article shows that contemporary journalism shares many similarities with the approaches found in culural journalism, such as interpre- tation, emotionality, and subjectivity. -

Key Concepts of Journalism

Key Concepts of Journalism - Providing information that the public needs to know: Many publications are devoted solely to information that the public wants to know; fashion and celebrity gossip magazines are good examples of this. Ideally, however, journalists strive to write less sensational stories because they are important for readers to know about. SPJ's Code of Ethics emphasizes that good news judgment includes publishing stories because "the American people must be well informed in order to make decisions regarding their lives, and their local and national communities. - Giving a fair and truthful account of news: There is a great deal of talk about bias in the media. Many journalists believe that if a publication is being criticized for being too liberal by some and too conservative by others, it is doing a good job. On its Web site, the Associated Press defines fair and truthful as "reliability and objectivity with reports that are accurate, balanced and informed." - Emphasizing the importance of free speech: Journalists define freedom of speech and of the press in very broad terms. Many journalists have an absolutist approach to discussing free speech, meaning that they believe no limits whatsoever on speech should be imposed. Free speech and a free press are essential for journalism to exist the way it does in this country, able to criticize the government and conduct investigations. In its mission statement, SPJ refers to freedom of speech and of the press as "the cornerstone of our nation and our liberty." - Spurring people to action: Swanson said journalism is a service-oriented profession because journalism "isn't just about providing raw information.