Mali: the Day the Music Stopped

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tuareg Music and Capitalist Reckonings in Niger a Dissertation Submitted

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Rhythms of Value: Tuareg Music and Capitalist Reckonings in Niger A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Ethnomusicology by Eric James Schmidt 2018 © Copyright by Eric James Schmidt 2018 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Rhythms of Value: Tuareg Music and Capitalist Reckonings in Niger by Eric James Schmidt Doctor of Philosophy in Ethnomusicology University of California, Los Angeles, 2018 Professor Timothy D. Taylor, Chair This dissertation examines how Tuareg people in Niger use music to reckon with their increasing but incomplete entanglement in global neoliberal capitalism. I argue that a variety of social actors—Tuareg musicians, fans, festival organizers, and government officials, as well as music producers from Europe and North America—have come to regard Tuareg music as a resource by which to realize economic, political, and other social ambitions. Such treatment of culture-as-resource is intimately linked to the global expansion of neoliberal capitalism, which has led individual and collective subjects around the world to take on a more entrepreneurial nature by exploiting representations of their identities for a variety of ends. While Tuareg collective identity has strongly been tied to an economy of pastoralism and caravan trade, the contemporary moment demands a reimagining of what it means to be, and to survive as, Tuareg. Since the 1970s, cycles of drought, entrenched poverty, and periodic conflicts have pushed more and more Tuaregs to pursue wage labor in cities across northwestern Africa or to work as trans- ii Saharan smugglers; meanwhile, tourism expanded from the 1980s into one of the region’s biggest industries by drawing on pastoralist skills while capitalizing on strategic essentialisms of Tuareg culture and identity. -

Country Office

Country Office Humanitarian Situation Report No. 8 © UNICEF/318A6918/Dicko Reporting Period: 1 January - 31 December 2019 Highlights Situation in Numbers • As of 31 December 2019, 201,429 internally displaced persons (IDPs) were 2,180,000 reported in the country, mainly located in Mopti, Gao, Segou, Timbuktu children in need of humanitarian and Menaka regions. assistance (Mali HRP revised July 2019) • In 2019, UNICEF provided short term emergency distribution of household water treatment and hygiene kits as well as sustainable water supply services to 224,295 people (158,021 for temporary access and 66,274 for 3,900,000 sustainable access) of which 16,425 in December 2019 in Segou, Mopti, people in need Gao, Menaka and Timbuktu regions. (OCHA July 2019) • 135,652 children aged 6 to 59 months were treated for severe acute 201,429 malnutrition in health centers across the country from January to Internally displaced people December 31, 2019. (Commission of Movement of Populations Report, 19 December 2019) • In 2019, UNICEF provided 121,900 children affected by conflict with psychosocial support and other child protection services, of which 7,778 were reached in December 2019. 1,113 Schools closed as of 31st • The number of allegations of recruitment and use by armed groups have December 2019 considerably increased (119 cases only in December) (Education Cluster December • From October to December, a total of 218 schools were reopened (120 in 2019) Mopti region) of which 62 in December. In 2019, 71,274 crises-affected children received learning material through UNICEF΄s support. UNICEF Appeal 2019 US$ 47 million UNICEF’s Response and Funding Status Funding Status* (in US$) Funds received, $11.8M Funding Carry- gap, forward, $28.5M $6.6M *Funding available includes carry-over and funds received in the current year. -

Lessons Learnt from the Reconstruction of the Destroyed Mausoleums of Timbuktu, Mali Thierry Joffroy, Ben Essayouti

Lessons learnt from the reconstruction of the destroyed mausoleums of Timbuktu, Mali Thierry Joffroy, Ben Essayouti To cite this version: Thierry Joffroy, Ben Essayouti. Lessons learnt from the reconstruction of the destroyed mausoleums of Timbuktu, Mali. HERITAGE2020 (3DPast | RISK-Terra) International Conference, Sep 2020, Valencia, Spain. pp.913-920, 10.5194/isprs-archives-XLIV-M-1-2020-913-2020. hal-02928898 HAL Id: hal-02928898 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02928898 Submitted on 9 Sep 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. The International Archives of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences, Volume XLIV-M-1-2020, 2020 HERITAGE2020 (3DPast | RISK-Terra) International Conference, 9–12 September 2020, Valencia, Spain LESSONS LEARNT FROM THE RECONSTRUCTION OF THE DESTROYED MAUSOLEUMS OF TIMBUKTU, MALI T. Joffroy 1, *, B. Essayouti 2 1 CRAterre-ENSAG, AE&CC, Univ. Grenoble Alpes, Grenoble, France - [email protected] 2 Mission culturelle de Tombouctou, Tombouctou, Mali - [email protected] Commission II - WG II/8 KEY WORDS: World heritage, Post conflict, Reconstruction, Resilience, Traditional conservation ABSTRACT: In 2012, the mausoleums of Timbuktu were destroyed by members of the armed forces occupying the North of Mali. -

Floods Briefing Note – 06 September 2018

MALI Floods Briefing note – 06 September 2018 Heavy rain that began in late July 2018 has caused flooding in several parts of the country. As of late August, more than 18,000 people were affected, 3,200 houses destroyed, and some 1,800 head of cattle killed. The affected populations are in need of shelter, NFI, and WASH assistance. Longer-term livelihoods assistance is highly likely to be needed in the aftermath of the floods. Source: UNICEF 05/10/2014 Anticipated scope and scale Key priorities Humanitarian constraints The rainy season in Mali is expected to continue until October, +18,000 Flooding of roads may delay the response. which will probably cause further flooding. The recrudescence of acts of banditry, people affected looting, kidnappings, and violence Flooding will have a longer-term impact on already vulnerable committed against humanitarian actors is populations affected by conflict, displacement, and drought. 3,200 hindering the response. Crop and cattle damage is likely to negatively impact both houses destroyed food security and livelihoods, and long-term assistance will be needed to counteract the effects of the floods. cattle killed Limitations 1,800 The lack of disaggregated data (both geographic and demographic) limits the evaluation of needs and the identification of specific Livelihoods vulnerabilities. impacted in the long term Any questions? Please contact our senior analyst, Jude Sweeney: [email protected] / +41 78 783 48 25 ACAPS Briefing Note: Floods in Mali Crisis impact peak during the rainy season (between May and October). The damage caused by flooding is increasing the risk of malaria. (WHO 01/05/2018, Government of Mali 11/06/2017) The rainy season in Mali runs from mid-May until October, causing infrastructural WASH: Access to safe drinking water and WASH facilities is poor in Timbuktu region, damage and impacting thousands of people every year. -

USAID MALI CIVIC ENGAGEMENT PROGRAM (CEP-MALI) Year 4 Report (October 01, 2019 – December 31, 2019)

USAID MALI CIVIC ENGAGEMENT PROGRAM (CEP-MALI) Year 4 Report (October 01, 2019 – December 31, 2019) Celebration of the International Day of Persons with Disabilities, December 3rd, 2019 Funding provided by the United States Agency for International Development under Cooperative Agreement No. AID-688-A-16-00006 January 2020 Prepared by: FHI 360 Submitted to: USAID Salimata Marico Robert Schmidt Agreement Officer’s Representative/AOR Agreement Officer [email protected] [email protected] Inna Bagayoko Cheick Oumar Coulibaly Alternate AOR Acquisition and Assistance Specialist [email protected] [email protected] 0 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page i LIST OF ACRONYMS ARPP Advancing Reconciliation and Promoting Peace AOR Agreement Officer Representative AAOR Alternate Agreement Officer Representative AMPPT Association Malienne des Personnes de Petite Taille AFAD Association de Formation et d’Appui du Développement AMA Association Malienne des Albinos ACCORD Appui à la Cohésion Communautaire et les Opportunités de Réconciliation et de Développement CEP Civic Engagement Program CMA Coordination des Mouvements de l’Azawad COR Contracting Officer Representative COP Chief of Party CPHDA Centre de Promotion des Droits Humains en Afrique CSO Civil Society Organization DCOP Deputy Chief of Party DPO Disabled Person’s Organization EOI Expression of Interest FHI 360 Family Health International 360 FONGIM Fédération des Organisations Internationales Non Gouvernementales au Mali FY Fiscal Year GGB Good Governance Barometer GOM Government of Mali INGOS International -

Mali Enhanced Market Analysis 2019

FEWS NET Mali Enhanced Market Analysis 2019 MALI ENHANCED MARKET ANALYSIS JUNE 2019 This publication was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development. It was prepared by Chemonics International Inc. for the Famine Early Warning Systems Network (FEWS NET), contract number AID-OAA-I-12-00006. The authors’Famine views Early expressed Warning inSystem this publications Network do not necessarily reflect the views of the 1 United States Agency for International Development or the United States government. FEWS NET Mali Enhanced Market Analysis 2019 About FEWS NET Created in response to the 1984 famines in East and West Africa, the Famine Early Warning Systems Network (FEWS NET) provides early warning and integrated, forward-looking analysis of the many factors that contribute to food insecurity. FEWS NET aims to inform decision makers and contribute to their emergency response planning; support partners in conducting early warning analysis and forecasting; and provide technical assistance to partner-led initiatives. To learn more about the FEWS NET project, please visit www.fews.net. Disclaimer This publication was prepared under the United States Agency for International Development Famine Early Warning Systems Network (FEWS NET) Indefinite Quantity Contract, AID-OAA-I-12-00006. The authors’ views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States government. Acknowledgments FEWS NET gratefully acknowledges the network of partners in Mali who contributed their time, analysis, and data to make this report possible. Recommended Citation FEWS NET. 2019. Mali Enhanced Market Analysis. Washington, DC: FEWS NET. -

A Peace of Timbuktu: Democratic Governance, Development And

UNIDIR/98/2 UNIDIR United Nations Institute for Disarmament Research Geneva A Peace of Timbuktu Democratic Governance, Development and African Peacemaking by Robin-Edward Poulton and Ibrahim ag Youssouf UNITED NATIONS New York and Geneva, 1998 NOTE The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. * * * The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the United Nations Secretariat. UNIDIR/98/2 UNITED NATIONS PUBLICATION Sales No. GV.E.98.0.3 ISBN 92-9045-125-4 UNIDIR United Nations Institute for Disarmament Research UNIDIR is an autonomous institution within the framework of the United Nations. It was established in 1980 by the General Assembly for the purpose of undertaking independent research on disarmament and related problems, particularly international security issues. The work of the Institute aims at: 1. Providing the international community with more diversified and complete data on problems relating to international security, the armaments race, and disarmament in all fields, particularly in the nuclear field, so as to facilitate progress, through negotiations, towards greater security for all States and towards the economic and social development of all peoples; 2. Promoting informed participation by all States in disarmament efforts; 3. Assisting ongoing negotiations in disarmament and continuing efforts to ensure greater international security at a progressively lower level of armaments, particularly nuclear armaments, by means of objective and factual studies and analyses; 4. -

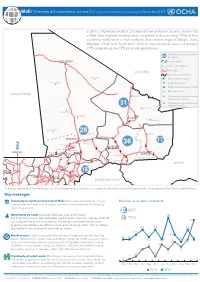

Humanitarian Access (Summary of Constraints from January to December 2017)

Mali: Overview of humanitarian access (summary of constraints from January to December 2017) In 2017, OCHA recorded 133 cases of humanitarian access constraints in Mali (the highest number ever recorded in the country). 97% of the incidents took place in the northern and central regions (Mopti, Gao, Ménaka, Kidal and Timbuktu). 41% of the incidents were robberies, 27% carjackings and 9% physical aggression. Number of access constraints xx by region TAOUDÉNIT Limit of region Limit of new regions ALGERIA Main road International boundaries Achourat! Non-functional airport Foum! Elba Functional airport Regional administrative centre ! Populated place MAURITANIA ! Téssalit Violence against humanitarian workers on locations Violence against humanitarian 31 workers on roads !Abeïbara ! Arawane Boujbeha! KIDAL ! Tin-Essako ! Anefif Al-Ourche! 28 ! Inékar Bourem! TIMBUKTU ! Gourma- 17 Rharous Goundam! 36 Diré! GAO 2 ! Niafunké ! Tonka ! BAMAKO Léré Gossi ! ! MÉNAKA Ansongo ! ! Youwarou! Anderamboukane Ouattagouna! Douentza ! NIGER MOPTI Ténénkou! 1 Bandiagara! 18 Koro! Bankass! SÉGOU Djenné! BURKINA FASO The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations. Key messages Insecurity in northern and central Mali: Both areas are experiencing an Number of access constraints unprecedented level of criminality, terrorism and armed conflict directly impeding access. 133 2017 Movement on road: Ansongo-Ménaka, Gao-Anefis-Kidal, 18 Timbuktu-Goundam, Bambara Maoudé-Timbuktu road axis are very difficult 68 2016 to navigate during the rainy season. Armed groups’presence requires 17 ongoing negotiations at different levels prior to using roads. Humanitarians are mostly victim of criminal activities on roads. 13 13 13 11 Aerial access: Existing airports allow access to regional capitals and big 11 9 9 9 cities in Bamako, Timbuktu, Gao and Mopti. -

Unemployed Intellectuals in the Sahara: the Teshumara Nationalist Movement and the Revolutions in Tuareg Societyã

IRSH 49 (2004), Supplement, pp. 87–109 DOI: 10.1017/S0020859004001658 # 2004 Internationaal Instituut voor Sociale Geschiedenis Unemployed Intellectuals in the Sahara: The Teshumara Nationalist Movement and the Revolutions in Tuareg Societyà Baz Lecocq Summary: In the past four decades the Tuareg, a people inhabiting the central Sahara, experienced dramatic socioeconomic upheaval caused by the national independence of the countries they inhabit, two droughts in the 1970s and 1980s, and prolonged rebellion against the state in Mali and Niger in the 1990s. This article discusses these major upheavals and their results from the viewpoint of three groups of Tuareg intellectuals: the ‘‘organic intellectuals’’ or traditional tribal leaders and Muslim religious specialists; the ‘‘traditional intellectuals’’ who came into being from the 1950s onwards; and the ‘‘popular intellectuals’’ of the teshumara movement, which found its origins in the drought-provoked economic emigration to the Maghreb, and which actively prepared the rebellions of the 1990s. By focusing on the debates between these intellectuals on the nature of Tuareg society, its organization, and the direction its future should take, the major changes in a society often described as guarding its traditions will be exposed. INTRODUCTION ‘‘In this still untamed Sahara – among the camel herdsmen, young Koranic students, government officials, and merchants now anticipating a more peaceful and prosperous future – we were seeking rhythms of life unbroken since the time of Muhammad, 1,300 years ago.’’1 When the Tuareg rebellions in Mali and Niger ended in the second half of the 1990s, journalists set out to look for the unchanging character of Saharan life, ruled by tradition and ways as old as mankind. -

Tuareg Guitar Music

BLOOMSBURY ENCYCLOPEDIA OF POPULAR MUSIC OF THE WORLD VOLUMES VIII–XIV: GENRES EDITED BY DAVID HORN AND JOHN SHEPHERD VOLUME XII GENRES: SUB-SAHARAN AFRICA EDITED BY HEIDI CAROLYN FELDMAN, DAVID HORN, JOHN SHEPHERD AND GABRIELLE KIELICH BLOOMSBURY ACADEMIC Bloomsbury Publishing Inc 1385 Broadway, New York, NY 10018, USA 50 Bedford Square, London, WC1B 3DP, UK BLOOMSBURY, BLOOMSBURY ACADEMIC and the Diana logo are trademarks of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc First published in the United States of America 2019 Copyright © Heidi Carolyn Feldman, David Horn, John Shepherd, Gabrielle Kielich, and Contributors, 2019 For legal purposes the Acknowledgments on pp. xviii–xix constitute an extension of this copyright page. Cover photograph: Alpha Blondy © Angel Manzano/Getty All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publishers. Bloomsbury Publishing Inc does not have any control over, or responsibility for, any third-party websites referred to or in this book. All internet addresses given in this book were correct at the time of going to press. The author and publisher regret any inconvenience caused if addresses have changed or sites have ceased to exist, but can accept no responsibility for any such changes. A catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress. ISBN: HB: 978-1-5013-4202-8 ePDF: 978-1-5013-4204-2 eBook: 978-1-5013-4203-5 Series: Encyclopedia of Popular Music of the World, volume 12 Typeset by Deanta Global Publishing Services, Chennai, India To find out more about our authors and books visit www.bloomsbury.com and sign up for our newsletters. -

The United Nations Foundation Team Traveled to Bamako, Gao, And

The United Nations Foundation team traveled to Bamako, Gao, and Timbuktu from September 16-26, 2018, to learn more about the United Nations Integrated Mission in Mali (MINUSMA). During our visit, we met with more than 50 UN officials, civil society groups, Western diplomats, and international forces including leadership in MINUSMA, Barkhane, and the G5 Sahel Joint Force. Below you will find our observations. Background The landlocked country of Mali, once a French colony and a cultural hub of West Africa, was overrun in January 2012 by a coalition of Tuareg and terrorist groups moving south towards the capital of Bamako. At the time, the Tuareg movement (MNLA) in northern Mali held legitimate grievances against the government and aligned itself with Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) and Ansar Dine (Defenders of Faith), the Islamic militants and jihadists in the region. Simultaneously, a mutiny of soldiers launched a military coup d’ etat led by Captain Amadou Sonogo, who took power from then President Amadou Toumani Touré and dissolved government institutions, consequently leading to a complete collapse of institutions in the northern part of the country. This Tuareg movement declared Kidal, Gao, and Timbuktu an Independent State of Azawad by April 2012. However, soon after, the Tuareg move- ment was pushed out by the jihadists, Ansar Dine and Movement for Oneness and Jihad in West Africa (MUJAO).1 In the early days of the conflict, the UN and Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) put together a power-sharing framework which led to the resignation of President Toure. Dioncounda Traoré was subsequently appointed interim President and a transitional government was established. -

Habib Koité & Bamada

Cal Performances Presents Friday, April 3, 2009, 8pm Zellerbach Hall Habib Koité & Bamada Dirk Leunis Habib Koité voice, guitar Souleyman Ann drums, calabash, backing vocals Abdoul Wahib Berthé bass, kamale n’goni, backing vocals Kélétigui Diabaté balafon, violin Mahamadou Koné talking drum, doum doum, caragnan Boubacar Sidibé guitar, backing vocals, harmonica Made possible, in part, through funding from the Western States Arts Federation and the National Endowment for the Arts. Cal Performances’ 2008–2009 season is sponsored by Wells Fargo Bank. CAL PERFORMANCES 5 About the Artist About the Artist Malian guitarist Habib Koité is one of Africa’s creating a new pan-Malian approach that reflects Habib’s second album, Ma Ya, was released One of the keys to Habib’s success has been his most popular and recognized musicians. Habib his open-minded interest in all types of music. The in Europe in 1998 to widespread acclaim. It spent dedication to touring. A true road warrior, Habib was born in 1958 in Thiès, a Senegalese town along predominant style played by Habib is based on the an amazing three months at the top spot on the Koite & Bamada have performed nearly 1,000 the railway line connecting Dakar to Niger, where danssa, a popular rhythm from his native city of World Charts Europe. A subtle production which shows since 1994 and appeared on some of the his father worked on the construction of the tracks. Kayes. He calls his version danssa doso, a Bambara revealed a more acoustic, introspective side of world’s most prestigious concert stages. Habib has Six months after his birth, the Koité family re- term he coined that combines the name of the Habib’s music, Ma Ya was released in North also participated in a number of memorable theme turned to the regional capital of west Mali, Kayes, popular rhythm with the word for hunter’s music America by Putumayo World Music in early 1999 tours alongside other artists.