The Evolution of US Policy Towards the Southern Caucasus

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mammadov Azerbaijan's Geopolitical Identity.Indd

# 62 VALDAI PAPERS February 2017 www.valdaiclub.com AZERBAIJAN’S GEOPOLITICAL IDENTITY IN THE CONTEXT OF THE 21ST CENTURY CHALLENGES AND PROSPECTS Farhad Mammadov About the author: Farhad Mammadov PhD in Philosophy, Director, Center for Strategic Studies under the President of Azerbaijan The views and opinions expressed in this Paper are those of the author and do not represent the views of the Valdai Discussion Club, unless explicitly stated otherwise. AZERBAIJAN’S GEOPOLITICAL IDENTITY IN THE CONTEXT OF THE 21ST CENTURY CHALLENGES AND PROSPECTS The 21st century began with chaos in international relations, the growing multipolarity of the once unipolar world, and geographic determinism giving prominence to regional leaders, who are resisting unipolar projects and competing with each other in their geographical region. However, nation states have shown that they are still to be reckoned with. International organizations and transnational law enforcement agencies, which were created to fi ght transnational threats such as international terrorism, drug cartels and criminal organizations, have not increased their effi ciency. Nation states continue to shoulder the biggest burden of fi ghting the above threats. Globalization has stimulated integration and accelerated various global processes, but it has not made this world safer or more stable. The connection between national, regional and global security is growing stronger. The fact that transnational threats operate as a network has highlighted the importance of interaction between nation states in fi ghting these threats. But strained relations between the geopolitical power centers, contradictions between regional states and the revival of bloc mentality are hindering the civilized world from consolidating its resources. -

Politics Among Danish Americans in the Midwest, Ca. 1890-1914

The Bridge Volume 31 Number 1 Article 6 2008 Politics Among Danish Americans in the Midwest, ca. 1890-1914 Jorn Brondal Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/thebridge Part of the European History Commons, European Languages and Societies Commons, and the Regional Sociology Commons Recommended Citation Brondal, Jorn (2008) "Politics Among Danish Americans in the Midwest, ca. 1890-1914," The Bridge: Vol. 31 : No. 1 , Article 6. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/thebridge/vol31/iss1/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Bridge by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Politics Among Danish Americans in the Midwest, ca. 1890-1914 by J0rn Brnndal During the last decades of the nineteenth century and into the twentieth, ethnicity and religion played a vital role in shaping the political culture of the Midwest. Indeed, historians like Samuel P. Hays, Lee Benson, Richard Jensen (of part Danish origins), and Paul Kleppner argued that ethnoreligious factors to a higher degree than socioeconomic circumstances informed the party affiliation of ordinary voters.1 It is definitely true that some ethnoreligious groups like, say, the Irish Catholics and the German Lutherans boasted full fledged political subcultures complete with their own press, their own political leadership and to some extent, at least, their own ethnically defined issues. Somewhat similar patterns existed among the Norwegian Americans.2 They too got involved in grassroots level political activities, with their churches, temperance societies, and fraternal organizations playing an important role in modeling a political subculture. -

Russia's “Pivot to Asia”

Russia’s “Pivot to Asia”: The Multilateral Dimension Stephen Blank STEPHEN BLANK is a Senior Fellow at the American Foreign Policy Council. He can be reached at <[email protected]>. NOTE: Sections of this working paper draw on Stephen Blank, “Russian Writers on the Decline of Russia in the Far East and the Rise of China,” Jamestown Foundation, Russia in Decline Project, September 13, 2016. Working Paper, June 28, 2017 – Stephen Blank EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This paper explores the opportunities and challenges that Russia has faced in its economic pivot to Asia and examines the potential roadblocks to its future integration with the region with special regard to multilateral Asian institutions. Main Argument Despite the challenges Russia faces, many Russian writers and officials continue to insist that the country is making visible strides forward in its so-called pivot to Asia. Russia’s ability to influence the many multilateral projects that pervade Asia from the Arctic to Southeast Asia and increase its role in them represents an “acid test” of whether or not proclamations of the correctness of Russian policy can stand up to scrutiny. Such scrutiny shows that Russia is failing to benefit from or participate in these projects. The one exception, the Eurasian Union, has become an economic disappointment to both Russia and its other members. Russia is actually steadily losing ground to China in the Arctic, Central Asia, and North Korea. Likewise, in Southeast Asia Moscow has promoted and signed many agreements with members of ASEAN, only to fail to implement them practically. Since Asia, as Moscow well knows, is the most dynamic sector of the global economy, this failure to reform at home and implement the developmental steps needed to compete in Asia can only presage negative geoeconomic and geopolitical consequences for Russia as it steadily becomes increasingly marginalized in the region despite its rhetoric and diplomatic activity. -

Russia, China, and Usa in Central Asia.Indd

VALDAI DISCUSSION CLUB REPORT www.valdaiclub.com RUSSIA, CHINA, AND USA IN CENTRAL ASIA: A BALANCE OF INTERESTS AND OPPORTUNITIES FOR COOPERATION Timofey Bordachev, Wan Qingsong, Andrew Small MOSCOW, SEPTEMBER 2016 Authors Timofey Bordachev Programme Director of the Foundation for Development and Support of the Valdai Discussion Club, Director of the Center for Comprehensive European and International Studies at the National Research University – Higher School of Economics, Ph.D. in Political Science Andrew Small Senior Transatlantic Fellow, Asia program, German Marshall Fund of the United States Wan Qingsong Research Fellow of the Center for Russian Studies (the National Key Research Institute of Humanities and Social Sciences under the Ministry of Education of PRC), School of Advanced International and Area Studies at East China Normal University; Research Fellow of the Center for Co-development with Neighboring Countries (University - Based Think Tank of Shanghai); holds a Doctorate in Political Science The authors express their gratitude for assistance in preparing the report and selection of reference materials to Kazakova Anastasia, Research Assistant, Center for Comprehensive European and International Studies at the National Research University – Higher School of Economics. The views and opinions expressed in this report are those of the authors and do not represent the views of the Valdai Discussion Club, unless explicitly stated otherwise. Contents Introduction: The Challenge of Central Asia .........................................................................................................3 -

GLOBAL PROBLEMS for GLOBAL GOVERNANCE Valdai Discussion Club Grantees Report

Moscow, September 2014 valdaiclub.com GLOBAL PROBLEMS FOR GLOBAL GOVERNANCE Valdai Discussion Club Grantees Report Global Problems for Global Governance Valdai Discussion Club Grantees Report Moscow, September 2014 valdaiclub.com Authors This report was prepared within the framework of the Research Grants Alexander Konkov Program of the Foundation for (Russian Federation) Development and Support of the Valdai PhD in Political Science. Head of the Discussion Club. International Peer Review at the Analytical Center for the Government of the Russian The views and opinions of authors Federation, member of the Peer Сouncil at expressed herein do not necessarily state the Institute for Socio-Economic and Political or reflect those of the Valdai Discussion Research, visiting lecturer at the Moscow State Club, neither of any organizations University and at the Financial University the authors have been affiliated under the Government of the Russian with or may be affiliated in future. Federation, member of the board at the Russian Political Science Association The paper had been prepared by the authors before the outbreak Hovhannes Nikoghosyan of the Ukrainian crisis, and therefore (Armenia) the text of the report does not contain PhD in Political Science, visiting lecturer at any analysis of the events. the Russian-Armenian (Slavonic) University (Yerevan), research fellow at the Information and Public Relations Centre under the Administration of the President of Armenia (2010-2012), visiting scholar at Sanford School of Public Policy, Duke University (2012–2013) ISBN 978-5-906757-09-8 Contents 4 Introduction 8 Chapter 1. Russia in Global World 24 Chapter 2. Global Trends of Global Governance 24 2.1. -

V. Inozemtsev, “Russia's Economic Modernization: the Causes of A

Notes de l’Ifri Russie.Nei.Visions 96 Russia’s Economic Modernization: The Causes of a Failure Vladislav INOZEMTSEV September 2016 Russia/NEI Center The Institut français des relations internationales (Ifri) is a research center and a forum for debate on major international political and economic issues. Headed by Thierry de Montbrial since its founding in 1979, Ifri is a non-governmental, non-profit organization. As an independent think tank, Ifri sets its own research agenda, publishing its findings regularly for a global audience. Taking an interdisciplinary approach, Ifri brings together political and economic decision-makers, researchers and internationally renowned experts to animate its debate and research activities. With offices in Paris and Brussels, Ifri stands out as one of the few French think tanks to have positioned itself at the very heart of European and broader international debate. The opinions expressed in this text are the responsibility of the author alone. ISBN: 978-2-36567-616-8 © All rights reserved, Ifri, 2016 Cover: © Philippe Agaponov How to quote this document: Vladislav Inozemtsev, “Russia's Economic Modernization: The Causes of a Failure”, Russie.Nei.Visions, No. 96, September 2016. Ifri 27 rue de la Procession 75740 Paris Cedex 15 – FRANCE Tel.: +33 (0)1 40 61 60 00 – Fax : +33 (0)1 40 61 60 60 Email: [email protected] Ifri-Bruxelles Rue Marie-Thérèse, 21 1000 – Brussels – BELGIUM Tel.: +32 (0)2 238 51 10 – Fax : +32 (0)2 238 51 15 Email: [email protected] Website: Ifri.org Russie.Nei.Visions Russie.Nei.Visions is an online collection dedicated to Russia and the other new independent states (Belarus, Ukraine, Moldova, Armenia, Georgia, Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan). -

Siberian Goats and North American Deer: a Contextual Approach to the Translation of Russian Common Names for Alaskan Mammals CATHERINE HOLDER BLEE’

ARCTIC VOL. 42, NO. 3 (SEPTEMBER 1989) F! 227-231 Siberian Goats and North American Deer: A Contextual Approach to the Translation of Russian Common Names for Alaskan Mammals CATHERINE HOLDER BLEE’ (Received 1 September 1988; accepted in revised form 19 January 1989) ABSTRACT. The word iaman was used by 19th-century Russian speakers in Sitka, Alaska, to refer to locally procured artiodactyls. The term originally meant “domesticated goat” in eastern Siberia and has usually been translated as“wild sheep” or “wild goat” in the American context. Physical evidence in the formof deer bones recovered during archeological excavations dating to the Russian period in Sitka suggested a reexamination of the context in which the word iaman was used bythe Russians. Russian, English, Latin and German historical and scientific literature describing the animalwere examined for the context in which the word was used. These contexts and 19th-century Russian dictionary definitions equating wild goats with small deer substantiate the hypothesis that the word iuman referred to the Sitka black-tailed deer by Russian speakers living in Sitka. Key words: Alaskan mammals, Alaskan archeology, historical archeology, ethnohistory, Russian translation, southeast Alaska, faunal analysis, Russian America RI~SUMÉ.Le mot iaman était utilisé au XIXe siècle, par les locuteurs russes de Sitka en Alaska, pour se référer aux artiodactyles qui cons- tituaient une source d’approvisionnement locale. Ce terme signifiait à l’origine (( chèvre domestique )> dans la Sibérie de l’est et a généralement été traduit comme (( mouton sauvage >) ou (( chèvre sauvage )) dans le contexte américain. Des preuves physiques sous la forme d’os de cerfs trouvés au cours de fouilles archéologiques datant de la période russe à Sitka, indiquaient que le contexte dans lequel le mot iaman était utilisé par les Russes devaitêtre réexaminé. -

History with an Attitude: Alaska in Modern Russian Patriotic Rhetoric

Andrei A. Znamenski, Memphis/USA History with an Attitude: Alaska in Modern Russian Patriotic Rhetoric Guys, stop your speculations and read books. One of my re cent discoveries is Kremlev. Here is a real history of Russia. One reads his books and wants to beat a head against a wall from the realization of how much we lost due to corruption, treason and the stupidity of our rulers – tsars, general secret aries and presidents. What wonderful opportunities we had in the past and how much we have lost!1 A nationalist blogger about the ultra-patriotic popular his tory “Russian America: Discovered and Sold” (2005) by Sergei Kremlev In Russian-American relations, Alaska is doomed to remain a literary-political metaphor – some sort of a stylistic figure of speech whose original meaning faded away being re placed with an imagined one.2 Writer Vladimir Rokot (2007) On the afternoon of October 18, 1867, a Siberian Line Battalion and a detachment of the US Ninth Infantry faced each other on a central plaza of New Archangel (Figure 1), the capital of Russian America, prepared for the official ceremony of lowering the Russian flag and of raising the Stars and Stripes. This act was to finalize the transfer of Alaska (Figure 2) from Russia to the United States, which bought the territory for $ 7.2 million. At 4 PM, Captain Aleksei Peshchurov gave orders to lower the Russian flag. After this, Brigadier General Lovell Rousseau, a representative of the US Government, ordered the American flag to be raised. Salutes were fired. This ceremony ended a brief seventy-year presence of the Russian Empire in northwestern North America.3 Driven by short-term strategic goals, Russian emperor Alexander II decided to get rid of his overseas posses sion, which represented 6 per cent of the Russian Empire territory. -

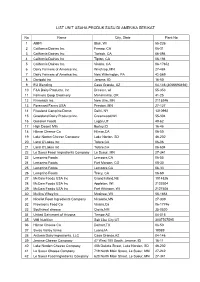

List Unit Usaha Produk Susu Di Amerika Serikat

LIST UNIT USAHA PRODUK SUSU DI AMERIKA SERIKAT No Name City, State Plant No 1 AMPI Blair, WI 55-226 2 California Dairies Inc. Fresno, CA 06-31 3 California Dairies Inc. Turlock, CA 06-094 4 California Dairies Inc. Tipton, CA 06-194 5 California Dairies Inc. Visalia, CA 06-17652 6 Dairy Farmers of America Inc. Winthrop, MN 27-484 7 Dairy Farmers of America Inc. New Wilmington, PA 42-569 8 Darigold Inc Jerome, ID 16-50 9 EU Blending Casa Grande, AZ 04-146 (3006693494) 10 F&A Dairy Products, Inc Dresser, wI 55-353 11 Farmers Coop Creamery Mcminnville, OR 41-25 12 Firmenich Inc. New Ulm, MN 2115246 13 Foremost Farms USA Preston, MN 27-127 14 Friesland Campina Domo Delhi, NY 1310992 15 Grassland Dairy Products Inc. Greenwood,WI 55-304 16 Gossner Foods Logan,UT 49-62 17 High Desert Milk Burley,ID 16-45 18 Hilmar Cheese Co Hilmar,CA 06-50 19 Lake Norton Cheese Company Lake Norton, SD 46-202 20 Land O'Lakes Inc Tulare,CA 06-06 21 Land O'Lakes Inc Tulare,CA 06-604 22 Le Sueur Food Ingredients Company Le Sueur, MN 27-341 23 Lemprino Foods Lemoore,CA 06-55 24 Lemprino Foods Fort Morgan, CO 08-30 25 Lemprino Foods Lemoore,CA 06-33 26 Lemprino Foods Tracy, CA 06-69 27 McCain Foods USA Inc Grand Island,NE 1914826 28 McCain Foods USA Inc Appleton, WI 2122504 29 McCain Foods USA Inc Fort Atkinson, WI 2127408 30 Mullins Whey Inc Mosinee, WI 55-1854 31 Nicollet Food Ingredients Company Nicolette,MN 27-339 32 Provisions Food Co Visalia,Ca 06-17746 33 Southwest cheese Clovis,NM 35-0520 34 United Dairyment of Arizona Tempe,AZ 04-015 35 VMI Nutrition Salt -

Azərbaycan Respublikasının Amerika Birləşmiş Ştatlarındakı Səfirliyi Embassy of the Republic of Azerbaijan to the United States of America

Azərbaycan Respublikasının Amerika Birləşmiş Ştatlarındakı Səfirliyi Embassy of the Republic of Azerbaijan to the United States of America April 4, 2014 The Honorable Jeanette K. White 35A Old Depot Rd., Putney, VT 05346 Dear Senator White, I am writing to you to express my deepest concern regarding the troubling news that a Senate Resolution 9 entitled “Senate Resolution Requesting That The President And Congress Of The United States Recognize The Independent Nagorno Karabakh Republic” was introduced on April 3, 2014 in the Vermont State Senate and was later referred to the Committee on Government Operations. This is a dangerous provocation which may seriously damage the very successful strategic partnership between the United States of America and Azerbaijan based on shared values and common interests. Furthermore, it clearly undermines America's interests in Eurasia. It is, in fact, rather counter-intuitive that at this crucial juncture when whole international community stands for the principle of territorial integrity in the case of Crimea in Ukraine, this resolution calls for recognition of puppet separatist regime non-recognized even by Armenia itself and created on the occupied Azerbaijani territories. Supporting Armenian separatism in Azerbaijan would be the same as supporting separatist enities in Georgia, Moldova and Ukraine. Not surprisingly, while Azerbaijan was among many progressive nations voting in the United Nations with the United States in support of Ukraine, Armenia was among only 11 nation voting with Russia against Ukraine. The other nations in the group included Iran, Cuba, Venezuela and others. In essence, the draft resolution would indicate Vermont's agreement with above narrow group of nations with strong anti-Western views. -

CURRICULUM VITAE Noriko Kawamura Department of History

CURRICULUM VITAE Noriko Kawamura Department of History Washington State University Pullman, WA 99164-4030 Phone: (509) 335-5428 Email: [email protected] EDUCATION June 1989 Doctor of Philosophy in History, University of Washington Major Fields: American diplomatic history, Japanese-American relations, modern Japan March 1982 Master of Arts in History, University of Washington Major Field: American diplomatic history March 1978 Bachelor of Arts in Humanities, Keio University, Tokyo, Japan Major Field: European history Dissertation: “Odd Associates in World War I: Japanese-American Relations, 1914-1918” EXPERIENCE Professor, Washington State University, Department of History, August 2019- Associate Professor, Washington State University, Department of History August 2000 to present Assistant Professor, tenure-track, Washington State University, Department of History August 1994 to June 2000 Assistant Professor, non-tenure-track, Washington State University, Department of History August 1992 to May 1994 Visiting Assistant Professor, University of Washington, Department of History June 1992 to August 1992 Assistant Professor, tenure-track, Virginia Military Institute, Department of History and Politics August 1989 to May 1992 PUBLICATIONS Books (Emperor Hirohito’s Cold War. Seattle: University of Washington Press, forthcoming in 2022.) Emperor Hirohito and the Pacific War. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2015. (Paperback 2017) Turbulence in the Pacific: Japanese-U.S. Relations during World War I. Westport, CT: Praeger, 2000. Building New Pathways to Peace. Co-edited with Yoichiro Murakami and Shin Chiba. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2011. Toward a Peaceable Future: Redefining Peace, Security and Kyosei from a Multidisciplinary Perspective. Co-edited with, Yoichiro Murakami and Shin Chiba. Pullman: The Thomas S. Foley Institute of Public Policy and Public Service, Washington State University Press, 2005. -

The 2020 Nagorno Karabakh Conflict from Iran's Perspective

INSTITUTE FOR SECURITY POLICY (ISP) WORKING PAPER THE 2020 NAGORNO - KARABAKH CONFLICT FROM IRAN’S PERSPECTIVE by Vali KALEJI Center for Strategic Studies (CSS) The COVID-19 pandemic: impact for the post-Soviet space and Russia’s aspirations VIENNA 2020 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................................ 3 II. CURRENT FLOW OF WAR IN NAGORNO-KARABAKH: SECURITY CONCERNS IN IRAN'S NORTHWESTERN BORDERS ................................................................................................................................. 5 III. IRAN SECURITY AND MILITARY REACTIONS .......................................................................................... 13 IV. IRAN’S DIPLOMATIC DYNAMISM ............................................................................................................. 17 V. ANALYZING IRAN’S FOREIGN POLICY TOWARD THE 2020 NAGORNO-KARABAKH CONFLICT ....... 26 VI. CONCLUSION ............................................................................................................................................. 29 1 ABOUT THE AUTHOR Dr. Vali Kaleji is an expert on Central Asia and Caucasian Studies in Tehran, Iran. His recent publications in Persian: The Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO): Goals, Functions and Perspectives (2010), South Caucasus as a Regional Security Complex, (2014), Political Developments in the Republic of Armenia, 1988- 2013 (2014), Iran, Russia and China in