Marcel Duchamp – Spring, 1911 – Where It

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Art Schools Burning and Other Songs of Love and War: Anti-Capitalist

Art Schools Burning and Other Songs of Love and War: Anti-Capitalist Vectors and Rhizomes By Gene Ray Kurfürstenstr. 4A D-10785 Berlin Email: [email protected] Ku’e! out to the comrades on the occupied island of O’ahu. Table of Contents Acknowledgments iv Preface: Is Another Art World Possible? v Part I: The One into Two 1 1. Art Schools Burning and Other Songs of Love and War 2 2. Tactical Media and the End of the End of History 64 3. Avant-Gardes as Anti-Capitalist Vector 94 Part II: The Two into... X [“V,” “R,” “M,” “C,”...] 131 4. Flag Rage: Responding to John Sims’s Recoloration Proclamation 132 5. “Everything for Everyone, and For Free, Too!”: A Conversation with Berlin Umsonst 152 6. Something Like That 175 Notes 188 Acknowledgments As ever, these textual traces of a thinking in process only became possible through a process of thinking with others. Many warm thanks to the friends who at various times have read all or parts of the manuscript and have generously shared their responses and criticisms: Iain Boal, Rozalinda Borcila, Gaye Chan, Steven Corcoran, Theodore Harris, Brian Holmes, Henrik Lebuhn, Thomas Pepper, Csaba Polony, Gregory Sholette, Joni Spigler, Ursula Tax and Dan Wang. And thanks to Antje, Kalle and Peter for the guided glimpse into their part of the rhizomes. With this book as with the last one, my wife Gaby has been nothing less than the necessary condition of my own possibility; now as then, my gratitude for that gift is more than I can bring to words. -

Duchamp with Lacan Through Žižek,On “The Creative Act”

Duchamp with Lacan through Žižek Duchamp’s Legacy As we approach both the fiftieth anniversary ofMarcel Duchamp’s death and the centenary of his most famous “readymade” it would appear that not a lot more can be said about the man and his work. And yet, most scholars would agree that, since Duchamp’s passing and the subsequent emergence of the enigmatic Étant Donnés, the reception of his oeuvre has become highly problematized. As Benjamin Buchloh notes in one of the most recent publications directly addressing this issue, the “near total silence” which has surroundedÉtant Donnés attests to the fact that Duchamp’s oeuvre has “fallen short of its actual historical potential.” (1) In an effort to break this silence and move beyond the impasse in question, many scholars have taken Étant Donnés as a point of departure for the reassessment of the Duchampian project. Through the peephole, this re-reading has involved an assessment of the erotic dimension of Duchamp’s work, primarily on the basis of Lacanian psychoanalysis. Some of the most important research in this area has been undertaken by two of the most prominent scholars in the field, Thierry de Duve and Rosalind Krauss. Krauss, for her part, was one of the first to explore the precise connections between Lacan and Duchamp when, in a chapter entitled “Notes on the Index” from her seminal 1986 work The Originality of the Avant-Garde and Other Modernist Myths, she uses Lacanian theory to unlock the mysteries of the Large Glass. First, she develops Lacan’s notion of the “mirror stage”: how -

Collected Writings

THE DOCUMENTS O F TWENTIETH CENTURY ART General Editor, Jack Flam Founding Editor, Robert Motherwell Other titl es in the series available from University of California Press: Flight Out of Tillie: A Dada Diary by Hugo Ball John Elderfield Art as Art: The Selected Writings of Ad Reinhardt Barbara Rose Memo irs of a Dada Dnnnmer by Richard Huelsenbeck Hans J. Kl ein sc hmidt German Expressionism: Dowments jro111 the End of th e Wilhelmine Empire to th e Rise of National Socialis111 Rose-Carol Washton Long Matisse on Art, Revised Edition Jack Flam Pop Art: A Critical History Steven Henry Madoff Co llected Writings of Robert Mothen/le/1 Stephanie Terenzio Conversations with Cezanne Michael Doran ROBERT SMITHSON: THE COLLECTED WRITINGS EDITED BY JACK FLAM UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESS Berkeley Los Angeles Londo n University of Cali fornia Press Berkeley and Los Angeles, California University of California Press, Ltd. London, England © 1996 by the Estate of Robert Smithson Introduction © 1996 by Jack Flam Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Smithson, Robert. Robert Smithson, the collected writings I edited, with an Introduction by Jack Flam. p. em.- (The documents of twentieth century art) Originally published: The writings of Robert Smithson. New York: New York University Press, 1979. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-520-20385-2 (pbk.: alk. paper) r. Art. I. Title. II. Series. N7445.2.S62A3 5 1996 700-dc20 95-34773 C IP Printed in the United States of Am erica o8 07 o6 9 8 7 6 T he paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of ANSII NISO Z39·48-1992 (R 1997) (Per111anmce of Paper) . -

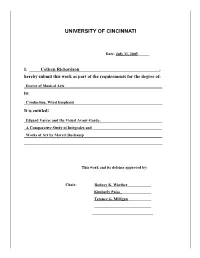

University of Cincinnati

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date: July 31, 2005______ I, Colleen Richardson , hereby submit this work as part of the requirements for the degree of: Doctor of Musical Arts in: Conducting, Wind Emphasis It is entitled: Edgard Varèse and the Visual Avant-Garde: A Comparative Study of Intégrales and Works of Art by Marcel Duchamp This work and its defense approved by: Chair: Rodney K. Winther____________ Kimberly Paice _______________ Terence G. Milligan____________ _____________________________ _______________________________ Edgard Varèse and the Visual Avant-Garde: A Comparative Study of Intégrales and Works of Art by Marcel Duchamp A document submitted to the Division of Research and Advanced Studies of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS in the Ensembles and Conducting Division of the College-Conservatory of Music 2005 by Colleen Richardson B.M., Brandon University, 1987 M.M., University of Calgary, 2001 Committee Chair: Rodney Winther ABSTRACT Edgard Varèse (1883–1965) had closer affiliations throughout his life with painters and poets than with composers, and his explanations or descriptions of his music resembled those of visual artists describing their own work. Avant-garde visual artists of this period were testing the dimensional limits of their arts by experimenting with perspective and concepts of space and time. In accordance with these artists, Varèse tested the dimensional limits of his music through experimentation with the concept of musical space and the projection of sounds into such space. Varèse composed Intégrales (1925) with these goals in mind after extended contact with artists from the Arensberg circle. Although more scholars are looking into Varèse’s artistic affiliations for insight into his compositional approach, to date my research has uncovered no detailed comparisons between specific visual works of art and the composer’s Intégrales. -

Copyright by Douglas Clifton Cushing 2014

Copyright by Douglas Clifton Cushing 2014 The Thesis Committee for Douglas Clifton Cushing Certifies that this is the approved version of the following thesis: Resonances: Marcel Duchamp and the Comte de Lautréamont APPROVED BY SUPERVISING COMMITTEE: Supervisor: Linda Dalrymple Henderson Richard Shiff Resonances: Marcel Duchamp and the Comte de Lautréamont by Douglas Clifton Cushing, B.F.A. Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts The University of Texas at Austin August 2014 Dedication In memory of Roger Cushing Jr., Madeline Cushing and Mary Lou Cavicchi, whose love, support, generosity, and encouragement led me to this place. Acknowledgements For her loving support, inspiration, and the endless conversations on the subject of Duchamp and Lautréamont that she endured, I would first like to thank my fiancée, Nicole Maloof. I would also like to thank my mother, Christine Favaloro, her husband, Joe Favaloro, and my stepfather, Leslie Cavicchi, for their confidence in me. To my advisor, Linda Dalrymple Henderson, I owe an immeasurable wealth of gratitude. Her encouragement, support, patience, and direction have been invaluable, and as a mentor she has been extraordinary. Moreover, it was in her seminar that this project began. I also offer my thanks to Richard Shiff and the other members of my thesis colloquium committee, John R. Clarke, Louis Waldman, and Alexandra Wettlaufer, for their suggestions and criticism. Thanks to Claire Howard for her additions to the research underlying this thesis, and to Willard Bohn for his help with the question of Apollinaire’s knowledge of Lautréamont. -

Marcel Duchamp'in Yapitlarina Çözümleyici Bir Katalog Çalişmasi Özlem Kalkan Erenus Işik Üniversitesi

MARCEL DUCHAMP’IN YAPITLARINA ÇÖZÜMLEYİCİ BİR KATALOG ÇALIŞMASI ÖZLEM KALKAN ERENUS IŞIK ÜNİVERSİTESİ MARCEL DUCHAMP’IN YAPITLARINA ÇÖZÜMLEYİCİ BİR KATALOG ÇALIŞMASI ÖZLEM KALKAN ERENUS İstanbul Üniversitesi, İşletme Fakültesi, İngilizce İşletme Bölümü, 1993 Bu Tez, Işık Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü’ne Yüksek Lisans (MA) derecesi için sunulmuştur. IŞIK ÜNİVERSİTESİ 2012 MARCEL DUCHAMP’IN YAPITLARINA ÇÖZÜMLEYİCİ BİR KATALOG ÇALIŞMASI Özet Bu tezin temel amacı, Marcel Duchamp’ın yapıtlar bütününün tek ve sürekli bir yapı içinde oluşumunu değerlendirmektir. Öncelikle yapıtları ve yaşamöyküsü bağlamında, Marcel Duchamp’ın zihinsel oluşumunu belirleyen evreler, etki kaynaklarıyla birlikte incelenmiştir. Sonraki bölümde yapıtları çözümlenerek, Marcel Duchamp’ın düşünsel yapısı sunulmuştur. İzleyen bölümde Duchamp’ın Dada ve Sürrealizm ile ilişkisi değerlendirilmiştir. Son olarak, tam bir gizlilik içinde yürütülen ve ancak ölümünden sonra sergilenen son büyük yapıtı incelenmiştir ve Marcel Duchamp’ın Yirminci Yüzyıl’ın en radikal estetik anlayışını getiren sanatçı olarak sunulması amaçlanmıştır. Anahtar Kelimeler: Marcel Duchamp, Büyük Cam, Hazır Yapım, Yeşil Kutu, Veriler, Yirminci Yüzyıl Sanatı, Dada, Sürrealizm i AN ANALYTICAL CATALOGUE STUDY ON MARCEL DUCHAMP’S WORKS Abstract The main aim of this thesis is to interprete the constitution of Marcel Duchamp’s corpus as a structure of single continuum. Primarily, in the context of his works and biography, the phases defining Marcel Duchamp’s intellectual formation, along with the influencing sources have been examined. In next part, by analyzing his works, Marcel Duchamp’s cogitative structure has been presented. In sequent part Duchamp’s relationship with Dada and Surrealism has been interpreted. Consequently, his last major work, which was carried out in complete secrecy and was exhibited only after his death, has been examined and to represent Marcel Duchamp as the developer of twentieth century’s most radical aesthetic conception has been aimed. -

“The Puppeteer of Your Own Past” Marcel Duchamp and the Manipulation of Posterity

“The Puppeteer of Your Own Past” Marcel Duchamp and the Manipulation of Posterity Michelle Anne Lee PhD The University of Edinburgh 2010 I, Michelle Lee, declare: (a) that the thesis has been composed by myself, and (b) that the work herein is my own, and (c) that the work herein has not been submitted for any other degree or professional qualification THE UNIVERSITY OF EDINBURGH AABBSSTTRRAACCTT OOFF TTHHEESSIISS Regulation 3.1.14 of the Postgraduate Assessment Regulations for Research Degrees refers These regulations are available via:- hhttp://www.acaffairs.ed.ac.uk/Regulations/Assessment/Home.htmttp://www.acaffairs.ed.ac.uk/Regulations/Assessment/Home.htm Name of Candidate: Michelle Lee Address : 5 (2F2) Edina Street Edinburgh Postal Code: EH7 5PN Degree: PhD by research Title of “The Puppeteer of Your Own Past” Thesis: Marcel Duchamp and the Manipulation of Posterity No. of words in the main text of Thesis: 94, 711 The image of Marcel Duchamp as a brilliant but laconic dilettante has come to dominate the literature surrounding the artist’s life and work. His intellect and strategic brilliance were vaunted by his friends and contemporaries, and served as the basis of the mythology that has been coalescing around the artist and his work since before his death in 1968. Though few would challenge these attributions of intelligence, few have likewise considered the role that Duchamp’s prodigious mind played in bringing about the present state of his career. Many of the signal features of Duchamp’s artistic career: his avoidance of the commercial art market, his cultivation of patrons, his “retirement” from art and the secret creation and posthumous unveiling of his Étant Donnés: 1˚ la chute d’eau/2˚ le gaz d’éclairage, all played key roles in the development of the Duchampian mythos. -

DADA / USA. Connections Between the Dada Movement and Eight American Fiction Writers

TESIS DOCTORAL Título DADA / USA. Connections between the Dada movement and eight American fiction writers Autor/es Rubén Fernández Abella Director/es Carlos Villar Flor Facultad Facultad de Letras y de la Educación Titulación Departamento Filologías Modernas Curso Académico DADA / USA. Connections between the Dada movement and eight American fiction writers, tesis doctoral de Rubén Fernández Abella, dirigida por Carlos Villar Flor (publicada por la Universidad de La Rioja), se difunde bajo una Licencia Creative Commons Reconocimiento-NoComercial-SinObraDerivada 3.0 Unported. Permisos que vayan más allá de lo cubierto por esta licencia pueden solicitarse a los titulares del copyright. © El autor © Universidad de La Rioja, Servicio de Publicaciones, 2017 publicaciones.unirioja.es E-mail: [email protected] UNIVERSIDAD DE LA RIOJA Facultad de Letras y de la Educación Departamento de Filologías Modernas PHD THESIS DADA / USA CONNECTIONS BETWEEN THE DADA MOVEMENT AND EIGHT AMERICAN FICTION WRITERS Rubén Fernández Abella Supervisor: Dr. Carlos Villar Flor 2016 Contents Acknowledgements 4 1. Introduction 1. 1. Purpose and Structure 5 1. 2. State of the Art 11 1. 3. Theoretical Framework 19 2. A Brief History of Dada 2. 1. The Birth of Dada 28 2. 2. New York Dada 36 2. 3. Paris Dada: The Demise of the Movement? 42 2. 4. Dada and Surrealism 45 3. Dada, Language, and Literature 3. 1. Dada’s Theory of Language 49 3. 2. Dada and the Novel: A Survey of Dadaist Fiction 52 3. 2. 1. Hugo Ball: Flametti oder vom Dandysmus der Armen and Tenderenda der Phantast 55 3. 2. 2. Kurt Schwitters: “Die Zwiebel” and Franz Müllers Drahtfrühling 60 3. -

Was Marcel Duchamp the Actual Anti-Artist?

Was Marcel Duchamp The Actual Anti-Artist? As a painter , Marcel Duchamp is difficult in order to categorize – yet he or she almost certainly needed it like that. During his / her career , just when everybody believed they recognized precisely what he or she had been , any Cubist, by way of example , or perhaps a Surrealist, he or she changed to another type as well as no-style, left city or land as well as stopped becoming an performer along with went off along with played chess inside tourneys. Duchamp also expended period wanting to determine precisely what fine art is actually. Along the way he or she produced “ready-mades” such as Fountain, a urinal with his pseudonym decorated on it. Could this specific professional product certainly be a thing of beauty ? Duchamp proposed it was as much as the particular person to determine. So, had been Marcel Duchamp the particular anti-artist? Please read on to learn : Marcel Duchamp was created inside Rouen, france inside 1887. Duchamp had been the fourth of eight brothers and sisters. His / her a pair of older bros , Gaston along with Raymond, and his awesome youthful sis Suzanne, also started to be artists. * - * Duchamp’s earliest art have been Impressionistic, such as the Church at Blainville (1902). Inside a spiel inside 1964, Duchamp stated , “My contact with Impressionism at that early on night out only agreed to be by using reproductions along with publications , because there were zero demonstrates of Impressionist painters inside Rouen until much later. Though 1 may refer to this as artwork ‘Impressionistic’ it demonstrates simply a really rural affect of Monet, my own puppy Impressionist at that time.” * - * Unless or else mentioned , all rates in the following paragraphs range from e-book , Marcel Duchamp by simply birth Ades, Neil Cox along with david Hopkins. -

Wayne Andersen, Marcel Duchamp: the Failed Messiah

Wayne Andersen, Marcel Duchamp: The Failed Messiah Wayne Andersen, Marcel Duchamp: The Failed Messiah (Geneva: Éditions Fabriart, 2010) This book is an insult to the intelligence of anyone who believes that Marcel Duchamp was an important and influential figure in the history of modern art in the early years of the 20th century. It’s subtitle-The Failed Messiah-tells you pretty much everything. While not technically an oxymoron, within this context, the words “failed” and “messiah” contradict one another, for by definition, a messiah is one who succeeds in his quest, and even Duchamp’s most ardent detractors would find it difficult to argue that he didn’t. Even the author of this book, Wayne Anderson-an 82-year-old retired professor of history and architecture at MIT (and also a doubtlessly disgruntled academic)-tells us that what Duchamp did to the history of art is comparable to the impact of the meteor that killed the dinosaurs. His use of the word “failed,” therefore, must apply specifically to his own personal point of view, for Andersen believes that the adulation accorded Duchamp by the art establishment is unjustified, blown far out of proportion to what he perceives are the artist’s actual accomplishments. Since Anderson’s myopic view is shared by preciously few, in writing this book he must have envisioned his own role as that of a messiah, someone who has valiantly stood up against all opposition to provide us with the correct path to aesthetic salvation, one that would have gone smoothly had Duchamp and his readymades not intervened. -

An Exit <Br>Marcel Duchamp and Jules Laforgue

An exit Marcel Duchamp and Jules Laforgue An exit Marcel Duchamp and Jules Laforgue Pieter de Nijs I ntroduction In 1887, the then famous actor Coquelin Cadet published an illustrated book called Le Rire. The illustrations were made by Eugène Bataille. One of these, showing Leonardo’s Mona Lisa smoking a pipe, can be regarded as a direct predecessor of Marcel Duchamp’s L.H.O.O.Q (1919). Bataille, better known as Sapeck, was an important member of the Incohérents, a group of artists who from 1882 on organized several exhibitions as alternatives for the official Salon. Parodies of famous pieces of art, political and social satire, and graphical puns were at the root of these exhibitions. Like their literary counterparts, who adorned themselves with such fantastic names as Hydropathes, Hirsutes, Zutistes, and Jemenfoutistes, the activities of the Incohérents were mainly aimed at ridiculing the official art world.The painters, writers, journalists, and cartoonists who participated in the activities of these artistic groups generally convened in the cabarets artistiques that sprang up in Paris in the last quarter of the nineteenth century, first on the rive gauche, in the Quartier Latin, later in Montmartre. Most of them published their work in the illustrated newspapers and magazines that appeared after the abolition of press censorship in 1881 and the emergence of new and faster (photomechanical) printing. These newspapers offered many writers and artists new opportunities to provide for their livelihood and to bring their work to the attention of a wider audience. The activities of groups like the Hydropathes and the Incohérents have long been seen solely as a means to “shock the bourgeois” (épater le bourgeois), as joking-for-joking’s- sake. -

Critical Play Radical Game Design

CRITICAL PLAY RADICAL GAME DESIGN MARY FLANAGAN Critical Play Critical Play Radical Game Design Mary Flanagan The MIT Press Cambridge, Massachusetts London, England © 2009 Massachusetts Institute of Technology All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by any elec- tronic or mechanical means (including photocopying, recording, or information storage and retrieval) without permission in writing from the publisher. MIT Press books may be purchased at special quantity discounts for business or sales pro- motional use. For information, please email [email protected] .edu or write to Special Sales Department, The MIT Press, 55 Hayward Street, Cambridge, MA 02142. This book was set in Janson and Rotis Sans by Graphic Composition, Inc., Bogart, Geor- gia, and was printed and bound in the United States of America. Library of Congress Cataloging- in-Publication Data Flanagan, Mary, 1969– Critical play : radical game design / Mary Flanagan. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-262-06268-8 (hardcover : alk. paper) 1. Games—Design and construction. 2. Games—Sociological aspects. 3. Art and popular culture. I. Title. GV1230.F53 2009 794.8Ј1536—dc22 2008041726 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Contents Preface and Acknowledgments vi 1 Introduction to Critical Play 1 2 Playing House 17 3 Board Games 63 4 Language Games 117 5 Performative Games and Objects 149 6 Artists’ Locative Games 189 7 Critical Computer Games 223 8 Designing for Critical Play 251 Notes 263 Bibliography 293 Index 319 Preface and Acknowledgments As both an artist and a writer, in order to give due focus on some of the ideas for Criti- cal Play, I have for the most part avoided discussion of my own work.