Napoleon on the Frontier

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Total Solar Eclipse of 2002 December 4

NASA/TP—2001–209990 Total Solar Eclipse of 2002 December 04 F. Espenak and J. Anderson Central Lat,Lng = -28.0 132.0 P Factor = 0.46 Semi W,H = 0.35 0.28 Offset X,Y = 0.00-0.00 1999 Oct 26 10:40:42 AM High Res World Data [WPD1] WorldMap v2.00, F. Espenak Orthographic Projection Scale = 8.00 mm/° = 1:13915000 Central Lat,Lng = -10.0 26.0 P Factor = 0.31 Semi W,H = 0.70 0.50 Offset X,Y = 0.00-0.00 1999 Oct 26 10:17:57 AM September 2001 The NASA STI Program Office … in Profile Since its founding, NASA has been dedicated to • CONFERENCE PUBLICATION. Collected the advancement of aeronautics and space papers from scientific and technical science. The NASA Scientific and Technical conferences, symposia, seminars, or other Information (STI) Program Office plays a key meetings sponsored or cosponsored by NASA. part in helping NASA maintain this important role. • SPECIAL PUBLICATION. Scientific, techni- cal, or historical information from NASA The NASA STI Program Office is operated by programs, projects, and mission, often con- Langley Research Center, the lead center for cerned with subjects having substantial public NASA’s scientific and technical information. The interest. NASA STI Program Office provides access to the NASA STI Database, the largest collection of • TECHNICAL TRANSLATION. aeronautical and space science STI in the world. English-language translations of foreign scien- The Program Office is also NASA’s institutional tific and technical material pertinent to NASA’s mechanism for disseminating the results of its mission. -

MARLA-OODNADATTA DISTRICT PROFILE: Characteristics4 and Challenges1,2

MARLA-OODNADATTA DISTRICT PROFILE: Characteristics4 and challenges1,2 South Australian Arid Lands NRM region Marla ABOUT THE MARLA- Oodnadatta OODNADATTA DISTRICT Algebuckina Innamincka Moomba The Marla-Oodnadatta Marla-Oodnadatta Marree-Innamincka district covers an area of Anna Creek approximately 132,000 Coober Pedy square kilometres (12% Coward Springs of South Australia in Curdimurka the north-west pastoral Marree region and is bounded Arkaroola Village Kingoonya by the Simpson Desert Andamooka Tarcoola Roxby Downs Leigh Creek and Lake Eyre to the Kingoonya Glendambo North Flinders Ranges east, the Great Victoria Woomera Desert to the west and Parachilna the Northern Territory border to the north. Hawker Gawler Ranges Legend North East Olary Port Augusta Iron Knob Waterways and Lakes Yunta Iron Baron National Parks and Reserves Whyalla Dog Fence COMMUNITIES VEGETATION WATER The permanent population of the district Major vegetation types include: The Great Artesian Basin provides an is approximately 2,000 people. Townships Plains: Mitchell grass, glassworts, poverty important source of water within the include Coober Pedy, Marla, Oodnadatta bush, saltbush, cannonball, neverfail, district. Natural venting occurs in the form and William Creek. bluebush, sea heath, samphire, twiggy sida, of mound springs, found predominately cottonbush, copper burr, pigface, prickly near the Oodnadatta Track. Waterholes CLIMATE wattle, mulga, lignum, cane grass. are found along major and minor drainage lines, some with the capacity to hold water The climate of the district is very arid Sandplains: Mulga, senna, marpoo, emu for over 12 months. with hot to extremely hot summers and bush, woollybutt, sandhill canegrass, mild, dry winters. Average annual rainfall copper burr, corkwood, dead finish, ranges between 120mm to 210mm across bluebush, saltbush. -

Coober Pedy, South Australia

The etymology of Coober Pedy, South Australia Petter Naessan The aim of this paper is to outline and assess the diverging etymologies of ‘Coober Pedy’ in northern South Australia, in the search for original and post-contact local Indigenous significance associated with the name and the region. At the interface of contemporary Yankunytjatjara and Pitjantjatjara opinion (mainly in the Coober Pedy region, where I have conducted fieldwork since 1999) and other sources, an interesting picture emerges: in the current use by Yankunytjatjara and Pitjantjatjara people as well as non-Indigenous people in Coober Pedy, the name ‘Coober Pedy’ – as ‘white man’s hole (in the ground)’ – does not seem to reflect or point toward a pre-contact Indigenous presence. Coober Pedy is an opal mining and tourist town with a total population of about 3500, situated near the Stuart Highway, about 850 kilometres north of Adelaide, South Australia. Coober Pedy is close to the Stuart Range, lies within the Arckaringa Basin and is near the border of the Great Victoria Desert. Low spinifex grasslands amounts for most of the sparse vegetation. The Coober Pedy and Oodnadatta region is characterised by dwarf shrubland and tussock grassland. Further north and northwest, low open shrub savanna and open shrub woodland dominates.1 Coober Pedy and surrounding regions are arid and exhibit very unpredictable rainfall. Much of the economic activity in the region (as well as the initial settlement of Euro-Australian invaders) is directly related to the geology, namely quite large deposits of opal. The area was only settled by non-Indigenous people after 1915 when opal was uncovered but traditionally the Indigenous population was western Arabana (Midlaliri). -

Qantas Domestic Australia Route Network

Qantas Domestic Route Network Effective 1 October 2018. Routes shown are indicative only 08:00 ARAFURA SEA 09:30 Thursday Island HORN ISLAND 10:00 Melville Island Maningrida GOVE (Nhulunbuy) DARWIN Oenpelli Jabiru ARNHEM WEIPA LAND Batchelor KAKADU CAPE GREAT Daly River Pine Creek Coen TIMOR SEA Groote Eylandt YORK Kalumburu Wadeye Katherine Ngukurr Gulf of PENINSULA CORAL Oombulgurri Carpentaria Wyndham Laura Cooktown SEA KIMBERLEY KUNUNURRA Borroloola Daly Waters MCARTHUR Mossman RIVER Port Douglas Mareeba Mungana CAIRNS Derby Newcastle Waters I NDIAN Kalkarindji Karumba Atherton BARRIER Normanton Burketown Tully BROOME Croydon OCEAN Halls Creek NORTHERN Doomadgee Georgetown Forsayth Ingham GULF TERRITORY TOWNSVILLE COUNTRY Tennant Creek Ayr Tanami Camooweal Kajabbi Bowen Charters Towers HAMILTON ISLAND PORT HEDLAND Julia Creek PROSERPINE Dampier GREAT SANDY DESERT MT ISA KARRATHA CLONCURRY Richmond Hughenden Marble Bar MACKAY REEF GREAT Onslow Barrow Creek Exmouth Pannawonica Telfer Dajarra QUEENSLAND LEARMONTH Solomon MORANBAH PILBARA Winton Saraji Tom Price Blair Athol Boulia Yeppoon PARABURDOO NEWMAN GIBSON DESERT EMERALD Jigalong ALICE SPRINGS LONGREACH Blackwater ROCKHAMPTON BARCALDINE GLADSTONE Areyonga CHANNEL Springsure Bedourie Biloela BLACKALL DIVIDING Moura Carnarvon Kaltukatjara Yaraka Monto BUNDABERG COUNTRY Theodore ULURU HERVEY BAY WESTERN Uluru Windorah Maryborough Finke SIMPSON DESERT Gayndah Birdsville Augathella Injune Warburton AUSTRALIA Amata Ernabella Gympie CHARLEVILLE Noosa Meekatharra ROMA Kingaroy Wiluna Quilpie -

Key Railway Crossings Overlay 113411.4 94795 ! Port Augusta ! !

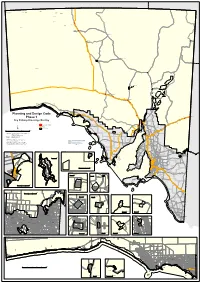

N O R T H E R N T E R R I T O R Y Amata ! Kalka Kanpi ! ! Nyapari Pipalyatjara ! ! Pukatja ! Yunyarinyi ! Umuwa ! QUEENSLAND Kaltjiti ! !113411.4 94795 Indulkana ! Mimili ! Watarru ! 113411.4 94795 Mintabie ! ! ! Marla Oodnadatta ! Innamincka Cadney Park ! ! Moomba ! WESTERN AUSTRALIA William Creek ! Coober Pedy ! Oak Valley ! Marree ! ! Lyndhurst Arkaroola ! Andamooka ! Roxby Downs ! Copley ! ! Nepabunna Leigh Creek ! Tarcoola ! Beltana ! 113411.4 94795 !! 113411.4 94795 Kingoonya ! Glendambo !113411.4 94795 Parachilna ! ! Blinman ! Woomera !!113411.4 94795 Pimba !113411.4 94795 Nullarbor Roadhouse Yalata ! ! ! Wilpena Border ! Village ! Nundroo Bookabie ! Coorabie ! Penong ! NEW SOUTH WALES ! Fowlers Bay FLINDERS RANGES !113411.4 94795 Planning and Design Code ! 113411.4 94795 ! Ceduna CEDUNA Cockburn Mingary !113411.4 94795 ! ! Phase 1 !113411.4 94795 Olary ! Key Railway Crossings Overlay 113411.4 94795 ! Port Augusta ! ! !113411.4 94795 Manna Hill ! STREAKY BAY Key Railway Crossings Yunta ! Iron Knob Railway MOUNT REMARKABLE ± Phase 1 extent PETERBOROUGH 0 50 100 150 km Iron Baron ! !!115768.8 17888 WUDINNA WHYALLA KIMBA Whyalla Produced by Department of Planning, Transport and Infrastructure Development Division ! GPO Box 1815 Adelaide SA 5001 Port Pirie www.sa.gov.au NORTHERN Projection Lambert Conformal Conic AREAS Compiled 11 January 2019 © Government of South Australia 2019 FRANKLIN No part of this document may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted PORT in any form, or by any means, without the prior written permission of the publisher, HARBOUR Department of Planning, Transport and Infrastructure. PIRIE ELLISTON CLEVE While every reasonable effort has been made to ensure that this document is correct at GOYDER the time of publication, the State of South Australia and its agencies, instrumentalities, employees and contractors disclaim any and all liability to any person in respect to anything or the consequence of anything done or omitted to be done in reliance upon the whole or any part of this document. -

Reportof the Chief Protector of Aboriginals for the Year Ended June

South BSS& Australia. REPORT CHIEF PROTECTOR OF ABORIGINALS FOR THE YEAR ENDED JUNE 30. 1925. R. E. E. Rogers Government Printer North Terrace. A 1925 Digitised by AIATSIS Library 2007, RS 25.5/1 - www.aiatsis.gov.au/library REPORT. Aboriginals Department, Adelaide, September 28th, 1925. Sir—I have the honor to submit this my report on the working of the Aboriginals Department for the year ended June 30th, 1925 ; also reports received from the Super intendents of the Aboriginal Stations and the Protectors of Aborigines in the North. POINT PEARCE STATION. The harvest results for the past season were disappointing in yield, wheat only averaging 9bush. per acre. However, as good prices for wheat, barley, and wool were obtained, the year's operations show a profit of £198 18s. 2d. The total rainfall for year ended December 31st, 1924, was 11.67in. Mr. W. R. Penhall resigned his position as Superintendent on October 31st, 1924, and Mr. J. B. Steer was transferred from Point McLeay to this position. Mr. Steer takes a keen interest in stock and agriculture and is well qualified for the position. POINT MCLEAY STATION. Owing to the increasing cost of firewood for this station, and the loss in return from the dairy, caused by the culling out of cows not up to standard, on the advice of the herd tester, also the drier season, this station shows a loss of £5,123 15s. l1d. The loss on the dairy will be only tem porary, as this system of herd testing will eventually make the dairy much more profitable, and we hope this year to reduce the cost of firewood, as we have arranged to cut and cart same with our own men and teams, instead of letting this contract to white men, which has been done previously. -

To View More Samplers Click Here

This sampler file contains various sample pages from the product. Sample pages will often include: the title page, an index, and other pages of interest. This sample is fully searchable (read Search Tips) but is not FASTFIND enabled. To view more samplers click here www.gould.com.au www.archivecdbooks.com.au · The widest range of Australian, English, · Over 1600 rare Australian and New Zealand Irish, Scottish and European resources books on fully searchable CD-ROM · 11000 products to help with your research · Over 3000 worldwide · A complete range of Genealogy software · Including: Government and Police 5000 data CDs from numerous countries gazettes, Electoral Rolls, Post Office and Specialist Directories, War records, Regional Subscribe to our weekly email newsletter histories etc. FOLLOW US ON TWITTER AND FACEBOOK www.unlockthepast.com.au · Promoting History, Genealogy and Heritage in Australia and New Zealand · A major events resource · regional and major roadshows, seminars, conferences, expos · A major go-to site for resources www.familyphotobook.com.au · free information and content, www.worldvitalrecords.com.au newsletters and blogs, speaker · Free software download to create biographies, topic details · 50 million Australasian records professional looking personal photo books, · Includes a team of expert speakers, writers, · 1 billion records world wide calendars and more organisations and commercial partners · low subscriptions · FREE content daily and some permanently South Australian Government Gazette 1888 Ref. AU5100-1888 ISBN: 978 1 74222 084 0 This book was kindly loaned to Archive CD Books Australia by Flinders University www.lib.flinders.edu.au Navigating this CD To view the contents of this CD use the bookmarks and Adobe Reader’s forward and back buttons to browse through the pages. -

Outback Tour

OUTBACK TOUR While at the Gawler Ranges we will reflect on in this town and the start of the Birdsville Track Charles Darke's exploratory work in 1844 on the heading north. Time permitting flights to Royal Geographical Society of S.A. Eyre Peninsula and travel along the Eyre Marree Man or Lake Eyre will be available from Highway, named after E J Eyre who broadly $280 - $430pp. trekked this area in 1840. The tour will also visit Woomera, internationally Finally the last night will be spent at Leigh Creek, with an Aboriginal Dreaming Stories known by session. The tour will go back to Adelaide via scientists and parts of another State geological treasure, the outer Flinders Ranges. The space John McDouall reconnoitrers of Stuart Expedition 1862 the 50s and 60s, and one of our newest towns, Roxby Downs, with a surface The Society proposes to undertake a 7 day 6 tour of Olympic Dam mine one of the world's night Outback Tour in October 2019. This tour richest deposits of copper, gold and uranium. will include the state geological treasure, the Whilst at Roxby Downs the special 123 km₂ Arid Gawler Ranges with its jutting rhyolite pillars Lands recovery project will be visited, at night, and hills topped in large, rounded granite so experiences are obtained of the special and domes. Visit Port Augusta, gateway to the unique fauna of our Outback including the Outback and the Arid Lands Botanic Gardens. burrowing bettong, greater sticknest rat, western barred bandicoot and the greater bilby. Weather permitting view our southern constellations by telescope, from Woomera. -

Pest Management Community Activities Volunteer Support Water

The SA Arid Lands NRM Board is responsible for overseeing Best practice soil conservation and grading workshop the management of natural resources over more than half of NAIDOC events at Ikara-Flinders Ranges South Australia – an area greater than 500,000 square Supported people from the SA Arid Lands Region to kilometres. This means its annual income of about $5million - attend training and development events including: Beef generated from a number of sources including grants and Week 2018; PIRSA - Stepping into Leadership program; levies - amounts to less than $10 per square kilometre. 2018 Thriving Women’s Conference; 2017 Australian Rangelands Society Conference; and SA Weeds To help the Board meet its responsibilities, a land-based Conference NRM levy and a NRM water levy are collected annually, Partnership with SheepConnect Pastoral for grazing providing critical leverage for the Board to obtain funding nutrition and reproductive efficiency workshops at Yunta from government and industry. In 2017/18 the Board’s and Hawker, as well as online webinars combined funding has contributed to the following activities: Volunteer support Pest management Support for Blinman Parachilna Pest Plant Control Group Wild dog management – trapper training, bi-annual bait volunteers who poisoned or removed more than 6000 injection service, subsidised baits and trapper cacti and contributed 3000 volunteer hours in 2017/18. reimbursement Sponsorship of the Great Tracks Clean Up Crew who, in Feral pig management workshop in North East Pastoral 2017/18, retrieved 63 tonnes of rubbish, 548 tyres and Expanded cat baiting trial onto privately owned land to travelled more than 2200km across the region. -

Beltana State Heritage Area: Guidelines, DEW Technical Report 2018/, Government of South Australia, Through Department for Environment and Water, Adelaide

Department for Environment and Water GPO Box 1047, Adelaide SA 5001 Telephone +61 (08) 8204 1910 Website www.environment.sa.gov.au Licensed under Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia License www.creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/au Copyright Owner: Crown in right of the state of South Australia 2018 © Government of South Australia 2018 Disclaimer While every reasonable effort has been made to verify the information in this fact sheet use of the information contained is at your sole risk. The Department recommends that you independently verify the information before taking any action. ISBN 978-1-921800-84-09 Preferred way to cite this publication Heritage South Australia, 2018, Beltana State heritage area: guidelines, DEW Technical report 2018/, Government of South Australia, through Department for Environment and Water, Adelaide Download this document at: http://www.environment.sa.gov.au Beltana State Heritage Area - DEW # 13886 SHA declared in 1987 The information in these Guidelines is advisory, to assist you in understanding the policies and processes for development in the State Heritage Area. It is recommended that you seek professional advice or contact the relevant State Heritage Adviser at the Department for Environment and Water (DEW) regarding any specific enquiries or for further assistance concerning the use and development of land. Being properly prepared can save you time and money in the long run. Contents 1. Introduction 1 1.1 Beltana State Heritage Area 1 1.2 Purpose of Guidelines 1 1.3 Getting Approval 1 1.4 Seeking Heritage Advice 1 2. History and Significance 3 2.1 History 3 2.2 Significance 3 2.3 Character and Setting 3 3. -

MARREE - INNAMINCKA Natural Resources Management Group

South Australian Arid Lands NRM Region MARREE - INNAMINCKA Natural Resources Management Group NORTHERN TERRITORY QUEENSLAND SIMPSON DESERT CONSERVATION PARK Pastoral Station ALTON DOWNS MULKA PANDIE PANDIE Boundary CORDILLO DOWNS Conservation and National Parks Regional reserve/ SIMPSON DESERT Pastoral Station REGIONAL RESERVE Aboriginal Land Marree - Innamincka CLIFTON HILLS NRM Group COONGIE LAKES NATIONAL PARK INNAMINCKA REGIONAL RESERVE SA Arid Lands NRM Region Boundary INNAMINCKA Dog Fence COWARIE Major Road MACUMBA ! KALAMURINA Innamincka Minor Road / Track MUNGERANIE Railway GIDGEALPA ! Moomba Cadastral Boundary THE PEAKE Watercourse LAKE EYRE (NORTH) LAKE EYRE MULKA Mainly Dry Lake NATIONAL PARK MERTY MERTY STRZELECKI ELLIOT PRICE REGIONAL CONSERVATION RESERVE PARK ETADUNNA BOLLARDS ANNA CREEK LAGOON DULKANINNA MULOORINA LINDON LAKE BLANCHE LAKE EYRE (SOUTH) MULOORINA CLAYTON MURNPEOWIE Produced by: Resource Information, Department of Water, Curdimurka ! STRZELECKI Land and Biodiversity Conservation. REGIONAL Data source: Pastoral lease names and boundaries supplied by FINNISS MARREE RESERVE Pastoral Program, DWLBC. Cadastre and Reserves SPRINGS LAKE supplied by the Department for Environment and CALLANNA ABORIGINAL ! Marree CALLABONNA Heritage. Waterbodies, Roads and Place names LAND FOSSIL supplied by Geoscience Australia. STUARTS CREEK MUNDOWDNA Projection: MGA Zone 53. RESERVE Datum: Geocentric Datum of Australia, 1994. MOOLAWATANA MOUNT MOUNT LYNDHURST FREELING FARINA MULGARIA WITCHELINA UMBERATANA ARKAROOLA WALES SOUTH NEW -

Water Supply and Governance Options for Outback Towns in South Australia

Water Supply and Governance Options for Outback Towns in South Australia Eileen Willis, Meryl Pearce, Bradley Jorgensen and John Martin Goyder Institute for Water Research Technical Report Series No. 15/7 www.goyderinstitute.org Goyder Institute for Water Research Technical Report Series ISSN: 1839-2725 The Goyder Institute for Water Research is a partnership between the South Australian Government through the Department of Environment, Water and Natural Resources, CSIRO, Flinders University, the University of Adelaide and the University of South Australia. The Institute will enhance the South Australian Government’s capacity to develop and deliver science-based policy solutions in water management. It brings together the best scientists and researchers across Australia to provide expert and independent scientific advice to inform good government water policy and identify future threats and opportunities to water security. Enquires should be addressed to: Goyder Institute for Water Research Level 1, Torrens Building 220 Victoria Square, Adelaide, SA, 5000 tel: 08-8303 8952 e-mail: [email protected] Citation Willis E. M., Pearce M. W., Jorgensen B. S., and Martin J. F., 2015, Water supply and governance options for outback towns in remote South Australia, Goyder Institute for Water Research Technical Report Series No. 15/7, Adelaide, South Australia Copyright © 2015 Flinders University To the extent permitted by law, all rights are reserved and no part of this publication covered by copyright may be reproduced or copied in any form or by any means except with the written permission of Flinders University. Disclaimer The participants advise that the information contained in this publication comprises general statements based on scientific research and does not warrant or represent the completeness of any information or material in this publication.