Atmospheric Environment Associated with Animal Flight

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Basic Concepts in Oceanography

Chapter 1 XA0101461 BASIC CONCEPTS IN OCEANOGRAPHY L.F. SMALL College of Oceanic and Atmospheric Sciences, Oregon State University, Corvallis, Oregon, United States of America Abstract Basic concepts in oceanography include major wind patterns that drive ocean currents, and the effects that the earth's rotation, positions of land masses, and temperature and salinity have on oceanic circulation and hence global distribution of radioactivity. Special attention is given to coastal and near-coastal processes such as upwelling, tidal effects, and small-scale processes, as radionuclide distributions are currently most associated with coastal regions. 1.1. INTRODUCTION Introductory information on ocean currents, on ocean and coastal processes, and on major systems that drive the ocean currents are important to an understanding of the temporal and spatial distributions of radionuclides in the world ocean. 1.2. GLOBAL PROCESSES 1.2.1 Global Wind Patterns and Ocean Currents The wind systems that drive aerosols and atmospheric radioactivity around the globe eventually deposit a lot of those materials in the oceans or in rivers. The winds also are largely responsible for driving the surface circulation of the world ocean, and thus help redistribute materials over the ocean's surface. The major wind systems are the Trade Winds in equatorial latitudes, and the Westerly Wind Systems that drive circulation in the north and south temperate and sub-polar regions (Fig. 1). It is no surprise that major circulations of surface currents have basically the same patterns as the winds that drive them (Fig. 2). Note that the Trade Wind System drives an Equatorial Current-Countercurrent system, for example. -

CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, NORTHRIDGE FORECASTING CALIFORNIA THUNDERSTORMS a Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Re

CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, NORTHRIDGE FORECASTING CALIFORNIA THUNDERSTORMS A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Master of Arts in Geography By Ilya Neyman May 2013 The thesis of Ilya Neyman is approved: _______________________ _________________ Dr. Steve LaDochy Date _______________________ _________________ Dr. Ron Davidson Date _______________________ _________________ Dr. James Hayes, Chair Date California State University, Northridge ii TABLE OF CONTENTS SIGNATURE PAGE ii ABSTRACT iv INTRODUCTION 1 THESIS STATEMENT 12 IMPORTANT TERMS AND DEFINITIONS 13 LITERATURE REVIEW 17 APPROACH AND METHODOLOGY 24 TRADITIONALLY RECOGNIZED TORNADIC PARAMETERS 28 CASE STUDY 1: SEPTEMBER 10, 2011 33 CASE STUDY 2: JULY 29, 2003 48 CASE STUDY 3: JANUARY 19, 2010 62 CASE STUDY 4: MAY 22, 2008 91 CONCLUSIONS 111 REFERENCES 116 iii ABSTRACT FORECASTING CALIFORNIA THUNDERSTORMS By Ilya Neyman Master of Arts in Geography Thunderstorms are a significant forecasting concern for southern California. Even though convection across this region is less frequent than in many other parts of the country significant thunderstorm events and occasional severe weather does occur. It has been found that a further challenge in convective forecasting across southern California is due to the variety of sub-regions that exist including coastal plains, inland valleys, mountains and deserts, each of which is associated with different weather conditions and sometimes drastically different convective parameters. In this paper four recent thunderstorm case studies were conducted, with each one representative of a different category of seasonal and synoptic patterns that are known to affect southern California. In addition to supporting points made in prior literature there were numerous new and unique findings that were discovered during the scope of this research and these are discussed as they are investigated in their respective case study as applicable. -

The Use of Hyperspectral Sounding Information to Monitor Atmospheric Tendencies Leading to Severe Local Storms

PUBLICATIONS Earth and Space Science RESEARCH ARTICLE The use of hyperspectral sounding information 10.1002/2015EA000122-T to monitor atmospheric tendencies leading Key Points: to severe local storms • Hyperspectral sounders add independent information to Elisabeth Weisz1, Nadia Smith1, and William L. Smith Sr.1 existing data sources • Time series of retrievals provides 1Cooperative Institute for Meteorological Satellite Studies, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, Wisconsin, USA valuable details to storm analysis • Forecasters are encouraged to utilize hyperspectral data Abstract Operational space-based hyperspectral sounders like the Atmospheric Infrared Sounder, the Infrared Atmospheric Sounding Interferometer, and the Cross-track Infrared Sounder on polar-orbiting satellites provide radiance measurements from which profiles of atmospheric temperature and moisture can Correspondence to: be retrieved. These retrieval products are provided on a global scale with the spatial and temporal resolution E. Weisz, [email protected] needed to complement traditional profile data sources like radiosondes and model fields. The goal of this paper is to demonstrate how existing efforts in real-time weather and environmental monitoring can benefit from this new generation of satellite hyperspectral data products. We investigate how retrievals from all four Citation: Weisz, E., N. Smith, and W. L. Smith Sr. operational sounders can be used in time series to monitor the preconvective environment leading up to the (2015), The use of hyperspectral sounding outbreak of a severe local storm. Our results suggest thepotentialbenefit of independent, consistent, and information to monitor atmospheric fi tendencies leading to severe local high-quality hyperspectral pro le information to real-time monitoring applications. storms, Earth and Space Science, 2, doi:10.1002/2015EA000122-T. -

Chapter 10: Cyclones: East of the Rocky Mountain

Chapter 10: Cyclones: East of the Rocky Mountain • Environment prior to the development of the Cyclone • Initial Development of the Extratropical Cyclone • Early Weather Along the Fronts • Storm Intensification • Mature Cyclone • Dissipating Cyclone ESS124 1 Prof. Jin-Yi Yu Extratropical Cyclones in North America Cyclones preferentially form in five locations in North America: (1) East of the Rocky Mountains (2) East of Canadian Rockies (3) Gulf Coast of the US (4) East Coast of the US (5) Bering Sea & Gulf of Alaska ESS124 2 Prof. Jin-Yi Yu Extratropical Cyclones • Extratropical cyclones are large swirling storm systems that form along the jetstream between 30 and 70 latitude. • The entire life cycle of an extratropical cyclone can span several days to well over a week. • The storm covers areas ranging from several Visible satellite image of an extratropical cyclone hundred to thousand miles covering the central United States across. ESS124 3 Prof. Jin-Yi Yu Mid-Latitude Cyclones • Mid-latitude cyclones form along a boundary separating polar air from warmer air to the south. • These cyclones are large-scale systems that typically travels eastward over great distance and bring precipitations over wide areas. • Lasting a week or more. ESS124 4 Prof. Jin-Yi Yu Polar Front Theory • Bjerknes, the founder of the Bergen school of meteorology, developed a polar front theory during WWI to describe the formation, growth, and dissipation of mid-latitude cyclones. Vilhelm Bjerknes (1862-1951) ESS124 5 Prof. Jin-Yi Yu Life Cycle of Mid-Latitude Cyclone • Cyclogenesis • Mature Cyclone • Occlusion ESS124 6 (from Weather & Climate) Prof. Jin-Yi Yu Life Cycle of Extratropical Cyclone • Extratropical cyclones form and intensify quickly, typically reaching maximum intensity (lowest central pressure) within 36 to 48 hours of formation. -

The Oakfield, Wisconsin, Tornado from 18-19 July 1996

The Oakfield, Wisconsin, Tornado from 18-19 July 1996 Brett Berenz Student at the University of Wisconsin Abstract On July 18th, 1996 an F5 tornado affected the region of Oakfield, Wisconsin. Leading up to the tornado, a warm moist air mass was in place at the surface. Along with veering winds and a cap the mesoscale pieces were in place for a spectacular event. The presence of a dry line as well as a cold front to trigger the severe weather was also in place. Further lifting was enhanced by a jet core aloft and diverging upper level winds. All in all, the storm cut a swath across southern Fond du Lac County and caused millions of dollars in damage while injuring 17 people. 1. Introduction and a clear cut path of for miles. This Wisconsin each year gets its fair storm also brought bouts of heavy rain share of severe weather. One of the and some hail as it moved across east- most memorable severe events on record central Wisconsin. Amazingly nobody in Wisconsin occurred on July 18th, was killed and only 17 people were 1996. At 7:15 p.m. (0015Z) a powerful injured as an entire town was nearly F5 tornado ripped through the tiny town demolished. Personal accounts told of a of Oakfield, Wisconsin, about 5 miles story that most were caught completely southwest of Fond du Lac in Fond du off guard as it had been a bright, warm Lac County. According to a CIMSS and sunny day, and sirens gave way only report damage estimates were around minutes before the actual tornado moved $40 million dollars and 47 of 320 homes into Oakfield. -

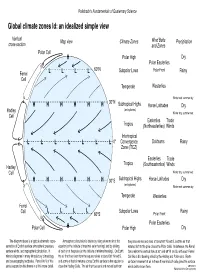

Global Climate Zones Id: an Idealized Simple View

Railsback's Fundamentals of Quaternary Science Global climate zones Id: an idealized simple view Vertical Map view Climate Zones Wind Belts Precipitation cross-section and Zones Polar Cell H Polar High Dry Polar Easterlies 60°N Subpolar Lows Polar Front Rainy Ferrel L L L L Cell Temperate Westerlies Winter wet; summer dry 30°N H H H H H H Subtropical Highs Horse Latitudes Dry (anticyclones) Hadley Winter dry; summer wet Cell Easterlies Trade Tropics (Northeasterlies) Winds Intertropical L L L L L L L 0° Convergence Doldrums Rainy Zone (ITCZ) Easterlies Trade Tropics (Southeasterlies) Winds Hadley Cell Winter dry; summer wet H H H H H H 30°S Subtropical Highs Horse Latitudes Dry (anticyclones) Winter wet; summer dry Temperate Westerlies Ferrel Cell L L L L Subpolar Lows Rainy 60°S Polar Front Polar Easterlies Polar Cell H Polar High Dry The diagram above is a typical schematic repre- Atmospheric circulation is driven by rising of warm air at the the poles warms and rises at about 60° N and S, and the air that sentation of Earth's surface atmospheric pressure, equator (at the latitude of maximal solar heating) and by sinking returns aloft to the pole closes the Polar Cells. In between, the Ferrel surface winds, and tropospheric circulation. It of cold air at the poles (at the latitude of minimal heating). On Earth, Cells mirror the vertical flow at 30° and 60° N and S, with each Ferrell mimics diagrams in many introductory climatology the air that has risen from the equator sinks at about 30° N and S, Cell like a ball bearing rolled by the Hadley and Polar cells. -

Glossary of Severe Weather Terms

Glossary of Severe Weather Terms -A- Anvil The flat, spreading top of a cloud, often shaped like an anvil. Thunderstorm anvils may spread hundreds of miles downwind from the thunderstorm itself, and sometimes may spread upwind. Anvil Dome A large overshooting top or penetrating top. -B- Back-building Thunderstorm A thunderstorm in which new development takes place on the upwind side (usually the west or southwest side), such that the storm seems to remain stationary or propagate in a backward direction. Back-sheared Anvil [Slang], a thunderstorm anvil which spreads upwind, against the flow aloft. A back-sheared anvil often implies a very strong updraft and a high severe weather potential. Beaver ('s) Tail [Slang], a particular type of inflow band with a relatively broad, flat appearance suggestive of a beaver's tail. It is attached to a supercell's general updraft and is oriented roughly parallel to the pseudo-warm front, i.e., usually east to west or southeast to northwest. As with any inflow band, cloud elements move toward the updraft, i.e., toward the west or northwest. Its size and shape change as the strength of the inflow changes. Spotters should note the distinction between a beaver tail and a tail cloud. A "true" tail cloud typically is attached to the wall cloud and has a cloud base at about the same level as the wall cloud itself. A beaver tail, on the other hand, is not attached to the wall cloud and has a cloud base at about the same height as the updraft base (which by definition is higher than the wall cloud). -

Chapter 7 – Atmospheric Circulations (Pp

Chapter 7 - Title Chapter 7 – Atmospheric Circulations (pp. 165-195) Contents • scales of motion and turbulence • local winds • the General Circulation of the atmosphere • ocean currents Wind Examples Fig. 7.1: Scales of atmospheric motion. Microscale → mesoscale → synoptic scale. Scales of Motion • Microscale – e.g. chimney – Short lived ‘eddies’, chaotic motion – Timescale: minutes • Mesoscale – e.g. local winds, thunderstorms – Timescale mins/hr/days • Synoptic scale – e.g. weather maps – Timescale: days to weeks • Planetary scale – Entire earth Scales of Motion Table 7.1: Scales of atmospheric motion Turbulence • Eddies : internal friction generated as laminar (smooth, steady) flow becomes irregular and turbulent • Most weather disturbances involve turbulence • 3 kinds: – Mechanical turbulence – you, buildings, etc. – Thermal turbulence – due to warm air rising and cold air sinking caused by surface heating – Clear Air Turbulence (CAT) - due to wind shear, i.e. change in wind speed and/or direction Mechanical Turbulence • Mechanical turbulence – due to flow over or around objects (mountains, buildings, etc.) Mechanical Turbulence: Wave Clouds • Flow over a mountain, generating: – Wave clouds – Rotors, bad for planes and gliders! Fig. 7.2: Mechanical turbulence - Air flowing past a mountain range creates eddies hazardous to flying. Thermal Turbulence • Thermal turbulence - essentially rising thermals of air generated by surface heating • Thermal turbulence is maximum during max surface heating - mid afternoon Questions 1. A pilot enters the weather service office and wants to know what time of the day she can expect to encounter the least turbulent winds at 760 m above central Kansas. If you were the weather forecaster, what would you tell her? 2. -

ESCI 107 – the Atmosphere Lesson 13 – Fronts and Midlatitude Cyclones

ESCI 107 – The Atmosphere Lesson 13 – Fronts and Midlatitude Cyclones Reading: Meteorology Today , Chapters 11 and 12 GENERAL A front is a boundary between two air masses. ο Usually there is a sharp temperature contrast across a front. ο There is often also a contrast in moisture across a front. ο There is a shift in wind direction across a front. Because the two air masses have different temperatures and different humidities they are of different density. The lighter air mass will overrun the denser air mass, which causes lifting along the frontal zone. This is why fronts are associated with clouds and precipitation. Because air masses are associated with areas of high pressure, and fronts separate these air masses, fronts themselves lie in regions of low pressure, or troughs. THE POLAR FRONT The polar front is a nearly continuous front that separates the polar easterly winds from the midlatitude westerlies. The position of the polar front is closely approximated by the position of the polar jet stream When a low-pressure system forms on the polar front then ο on the west side of the low, cold air is pushed southward as a cold front ο on the east side of the low, warm air is pushed northward as a warm front WARM FRONTS Warm air advances into region formerly covered by cold air. Weather map symbol is red line with circular teeth. Warm air rides up and over cold air. The frontal surface slopes very shallowly with height (about 1:200). The front moves forward at 15 - 20 mph. -

Chapter 8 – Atmospheric Circulation and Pressure Distribution Single

Chapter 8 – Atmospheric Circulation and Pressure Distribution Understanding Weather and Climate Aguado and Burt ATMO 1300 Single Cell Model • Strong heating at the equator caused air to rise, diverge towards the pole, sink back to the surface and returned to the equator. • Due to the Earth’s rotation the winds would move east to west. ATMO 1300 1 Single Cell Model ATMO 1300 Three Cell Model • Divides the circulations in each hemisphere into three cells: – Hadley Cell (tropics/subtropics) – Ferrel Cell (middle latitudes) – Polar Cell ATMO 1300 2 Three Cell Model Polar Cell Ferrel Cell Hadley Cell ATMO 1300 Hadley Cell • Strong solar heating leads to rising air which diverges towards the poles. – Creates Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ) • Aloft, air moves poleward but acquires a west to east motion. • Air descends at 20°-30° latitude to form subtropical highs. – Creates desert conditions • Air moves towards the equator at the surface and a weak Coriolis force creates the NE trade winds. ATMO 1300 3 Ferrel Cell • Indirectly caused by the turning of the Hadley and Polar cells. • Air flows north away from the subtropical high towards the subpolar lows, and acquires a large westerly component – westerlies ATMO 1300 Polar Cell • Surface air moves from polar highs to subpolar lows. – Subpolar lows are relatively warm – Polar highs are relatively cold • Coriolis forces directs the surface winds to the west creating the polar easterlies. ATMO 1300 4 Semi-Permanent Pressure Cells • Areas of high/low pressure that undergo seasonal changes in -

A New Look at the Super Outbreak of Tornadoes on 3–4 April 1974

JUNE 2002 LOCATELLI ET AL. 1633 A New Look at the Super Outbreak of Tornadoes on 3±4 April 1974 JOHN D. LOCATELLI,MARK T. S TOELINGA, AND PETER V. H OBBS Department of Atmospheric Sciences, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington (Manuscript received 24 May 2001, in ®nal form 5 December 2001) ABSTRACT The outbreak of tornadoes from the Mississippi River to just east of the Appalachian Mountains on 2±5 April 1974 is analyzed using conventional techniques and the Pennsylvania State University±National Center for Atmospheric Research ®fth-generation Mesoscale Model (MM5). The MM5 was run for 48 h using the NCEP± NCAR reanalysis dataset for initial conditions. It is suggested that the ®rst damaging squall line within the storm of 2±5 April 1974 (herein referred to as the Super Outbreak storm) was initiated by updrafts associated with an undular bore. The bore resulted from the forward advance of a Paci®c cold front into a stable air mass. The second major squall line within the Super Outbreak storm, which produced the strongest and most numerous tornadoes, was directly connected with the lifting associated with a cold front aloft. This second squall line was located along the farthest forward protrusion of a Paci®c cold front as it occluded with a lee trough/dryline. An important factor in the formation of this occluded structure was the diabatic effects of evaporative cooling ahead of the Paci®c cold front and daytime surface heating behind the Paci®c cold front. These effects combined to lessen the horizontal temperature gradient across the cold front within the boundary layer. -

Jet Stream, Which Can Lead to Rain Or Snow

cloudchart_back25.ai 1 7/31/2019 9:41:38 AM Be weatherwise wherever you are North of the cold front North of the warm front Strong winds from the high-pressure system carry colder, drier air into the dark blue area. As the cold front In the light blue area, the air tends to be cool and dry. Closer to This map shows a simplified forecast for a single, hypothetical day. passes, precipitation ends and skies clear fairly rapidly. the warm front, moisture increases. As a result, clouds thicken, The locations of the low- and high-pressure systems, jet stream, which can lead to rain or snow. and fronts shape the weather that a given region may experience. Possible impacts The difference in air pressure between two points determines wind speed and direction. Large pressure Possible impacts There can be hazardous weather anywhere, at any time. Begin differences cause very strong winds. They are more likely to occur in winter and can lead to blizzard conditions Warm fronts near areas of low-pressure can bring heavy rain, each day knowing the weather forecast. If severe or extreme and dangerous wind chills. In mountainous areas, lightning from thunderstorms with little or no rainfall can snow, or sleet. Rain can lead to flooding, while snow and sleet weather is a possibility, periodically check for forecast updates. ignite wildfires. These fires may spread rapidly when driven by strong winds associated with the thunderstorm. may result in a variety of hazards including slick roads and power outages. Be prepared with a safety plan. Have a “go-kit” with important Weather safety property and documents ready in case of emergency.