Small Company Big Mess Table of Contents

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

September 6 2016 This Is a Compilation of the Last 35 Pdf Share Threads and the Rpg Generals Threads

Da Archive September 6 2016 This is a compilation of the last 35 pdf share threads and the rpg generals threads. A HUGE THANK YOU to all contributors. It has been cleaned up some, labeled poorly, and shuffled about a little to perhaps be more useful. There are links to perhaps 17,000 pdfs. Don't be intimidated, some are duplicates. Go get a coffee and browse. As Anon says; “Surely in Da Archive™ somewhere.” Part I is the Personal Collections. They are Huge. You need to go to each one and look at them. They often have over 1000 links each. Part II is the Alphabetical Section. Well.... when I say “alphabetical”, I really mean artistically arranged according to my whim. Ctrl+F will be of little use in this document, you will have to wander around and look with your eyes. Please buy a copy of a book if you use it. No really, I mean it. The Negarons generated by struggling game publishers have been proven to psychically attach themselves to the dice of gamers who like a game enough to play it but not enough to support it. - - – - - – - - - – - - - - - --- – --- --- – - - - - - - - - - - – - - – - - - - - - – - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - – - - – - - - – - - - - - --- – --- --- – - - - - - - - - - - – - - – - - - - - - – - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Mixed Personal Big Collections – most have HUNDREDS of files These Are The LOTSASTUFF FILES --- – Tons & Tons & Tons o' goodies! LOTSASTUFF 's Awesome Reference Resources. City Builder, Magical Society, Historical Costumes, Name books, Central Casting, Encyclopedias, -

Dragon Magazine #203

Issue #203 Vol. XVIII, No. 9 March 1994 SPECIAL ATTRACTIONS Publisher TSR, Inc. Where science and fantasy collide Associate Publisher 9 Climb aboard for a wild ride of imagination. Brian Thomsen More Gamma Goodies Kim Eastland Editor-in-Chief 10 Equip your GAMMA WORLD® PCs with laser pens Kim Mohan and wrist rockets. Associate editor Terribly Twisted Technology Robin D. Laws Dale A. Donovan 14 Add these weird-tech items to an OVER THE EDGE* Fiction editor campaign. Barbara G. Young Lookin for work, chummer? Gregory W. Detwiler Editorial assistant Run these missions in FASAs SHADOWRUN* game. Wolfgang H. Baur 22 Art director Larry W. Smith BONUS The AMAZING ENGINE System Guide Production staff Tracey Isler 41 These rules explain the basics of the AMAZING ENGINE gameincluding the innovative player core Subscriptions concept. Janet L. Winters U.S. advertising Cindy Rick FICTION U.K. correspondent and U.K. advertising Spencers Peace Kurt Giambastiani Wendy Mottaz 96 A tale on the burdens of leadership. DRAGON® Magazine (ISSN 0279-6848) is published tion throughout the United Kingdom is by Comag monthly by TSR. Inc., P.O. Box 756 (201 Sheridan Magazine Marketing, Tavistock Road West Drayton, Springs Road) Lake Geneva WI 53147, United States Middlesex UB7 7QE United Kingdom telephone: of America The postal address for all materials from 0895-444055 the United States of America and Canada except Subscriptions: Subscription rates via second-class subscription orders is DRAGON® Magazine, P.O. Box mail are as follows $30 in U.S. funds for 12 issues 111, (201 Sheridan Springs Road), Lake Geneva WI sent to an address in the U.S.: $36 in U.S. -

August 12 2016 This Is a Compilation of the Last 31 Pdf Share Threads and the Rpg Generals Threads

Da Archive August 12 2016 This is a compilation of the last 31 pdf share threads and the rpg generals threads. A HUGE THANK YOU to all contributors. It has been cleaned up some, labeled poorly, and shuffled about a little to perhaps be more useful. There are links to perhaps 18,000 pdfs. Don't be intimidated, some are duplicates. Go get a coffee and browse. As Anon says; “Surely in Da Archive™ somewhere.” Part I is the Personal Collections. They are Huge. You need to go to each one and look at them. They often have over 1000 links each. Part II is the Alphabetical Section. Please buy a copy of a book if you use it. No really, I mean it. The Negarons generated by struggling game publishers have been proven to psychically attach themselves to the dice of gamers who like a game enough to play it but not enough to support it. - - – - - – - - - – - - - - - --- – --- --- – - - - - - - - - - - – - - – - - - - - - – - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - – - - – - - - – - - - - - --- – --- --- – - - - - - - - - - - – - - – - - - - - - – - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Mixed Personal Big Collections – most have HUNDREDS of files These Are The LOTSASTUFF FILES --- – Tons & Tons & Tons o' goodies! LOTSASTUFF 's Awesome Reference Resources. City Builder, Magical Society, Historical Costumes, Name books, Central Casting, Encyclopedias, Medieval Life, Mapping, World Building, Kobold's Guides, Spacefarer's Guide https://www.mediafire.com/folder/5yf71laq43c3z/References FOLDER ONE: ASOIAF, AD&D 1E 2E, CoC, Cyberpunk 2020, FGU, -

The Player Core & Player Character

Sample file System Guide Sample file Table of Contents Introduction and Welcome .. 2 Movement ..........................................2 3 The Player Core and Player Character . 4 Measurement ................................. 23 The Ability Pools . .. 5 Speed ............................................. 23 The Attributes . 5 Carrying Capacity ...................... ........ 24 Generming the Player Core and Player Pu~hing the Limits .............................. 24 Character . 6 Resnng ......................... ................. 25 Life and Death . 9 Vehicle:, anJ Special Movement ............... 25 Beyond the Core ................... .............. I I Combat ............................................. 25 Professions and Skills ... ..................... 12 Combat Sequence .............................. 26 Starring Skills ................................. 14 Advantage ........................ ..... ....... 26 Ahi li ry Checks ........ .. ....................... 15 Declaring Actions ........................... 27 Unski lled Characters ........................... 16 lntttattve .................................... 27 Margin Rattng ................................. 18 Hitung Your Target ........................ 28 Experience ....................................... 19 Target Are<ls ................. ................ 29 Awardmg and Earning Experience ......... 20 Ranged Comhat ................................. 30 Expcnence and Multiple Univer es ......... 20 Combat Modifier.. .............................. 30 Taxing Abilirie ................................ -

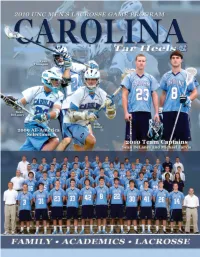

0910-Media-Guide.Pdf

Carolina Men’s Lacrosse • General Information & Table of Contents Carolina Lacrosse Quick Facts Chapel Hill, N.C. Table of Contents Location: 2010 Team Picture & Captains, 2009 All-Americas . .Front Cover Established: December 11, 1789 (UNC is the oldest public university in the United States) 2010 Top Returnees . .Inside Front Cover Enrollment: 17,136 undergraduates, 8,177 postgraduates UNC Quick Facts, Table of Contents . .Page 1 Chancellor: Holden Thorp Preseason Outlook With Head Coach Joe Breschi . .Page 2 Athletic Director: Dick Baddour 2010 Roster . .Page 4 Senior Associate Athletic Director for Olympic Sports: Beth Miller 2009 Statistics . .Page 5 NCAA Division I, Football Bowl Subdivision, 28 varsity sports Affiliation: The 2010 Tar Heels . .Page 6 Conference: Atlantic Coast Conference Nickname: Tar Heels 2010 Team Picture, 2009 Season Review Notes . .Page 26 School Colors: Carolina Blue and White UNC Athletic Department . .Page 27 Mascot: Rameses The Ram (Live for football, costumed for other sports) Head Coach Joe Breschi . .Page 28 Motto: Lux Libertas (Light and Liberty) Head Assistant Coach Pat Myers . .Page 30 Endowment: $2.16 billion Assistant Coaches Chris Fiefs & Brian Holman . .Page 31 3,295 Faculty: Lacrosse Support Staff, UNC in the Community . .Page 32 Campus: Suburban, 729 acres Athletic Department Web Site: www.TarHeelBlue.com Fetzer Field . .Page 33 University Website: www.unc.edu Lacrosse History . .Page 34 Carolina Men’s Lacrosse Information Year-by-Year Records & Finishes . .Page 38 Head Coach: Joe Breschi (North Carolina ‘90) Series Records . .Page 39 Record at UNC: 12-6, One Season All-Time Scores . .Page 41 Career Record: 104-69, 12 seasons (11 at Ohio State,1 at UNC) School Records . -

Dragon Magazine #194

SPECIAL ATTRACTIONS Issue #194 Vol. XVIII, No. 1 June 1993 9 Nothing gets your attention like a dragon Our annual tribute to our namesake-but with three new twists. Publisher James M. Ward Dragon Dogfights! Anne Brown 10 Battle it out with these aerial AD&D® rules for dragon miniatures. Editor Roger E. Moore The Dragon Project: Dexter & Cornelius Loyd Blankenship Associate editor 18 A (not very) ferocious dragon and a (not very) heroic ally for the Dale A. Donovan GURPS FANTASY* game. Fiction editor The Dragon Project: D.R.A.G.O.N-bot ver. 3.1 Ed Stark Barbara G. Young 20 Hell on wheels . not! A Troubleshooters nightmare for the PARANOIA* game. Editorial assistant Wolfgang H. Baur FEATURES Art director Larry W. Smith The Known World Grimoire Bruce A. Heard Production staff 41 Why did my flying castle crash? The Day of Dread and other D&D® Gaye OKeefe Tim Coumbe game queries answered. Subscriptions Breaking Them In Neil McGarry Janet L. Winters 44 Turn your groups novice gamers into old hands with these easy suggestions. U.S. advertising Cindy Rick Get Ready, Get Set, Go! Tom McLaughlin U.K. correspondent 48 Hit the gaming heights at the 1993 GEN CON® Game Fair! and U.K. advertising Wendy Mottaz The Official Ballot for the 1991 & 1992 ORIGINS* Awards 51 Two years in onevote now for the best games in existence! DRAGON® Magazine (ISSN 0279-6848) is published ution throughout the United Kingdom is by Comag monthly by TSR, Inc., P.O. Box 756 (201 Sheridan Magazine Marketing, Tavistock Road, West Drayton. -

Catalog of Rpgs

Compiled by: [email protected] Updated: 7/16/03 Catalog Of RPGs 9th Level Games Kobolds Ate My Baby! Ninja Burger: The RPG! ACE Books ACE Fantasy ElfQuest Adept Press Sorcerer Adventure Publications Fantasy Comics Adventure Simulations Super Squadron Adventures Unlimited Adventures in Fantasy AEG 7th Sea Art Books Brave New World Farscape Legend of the Five Rings Legend of the Five Rings CCG Shadis Magazine Warlord Agents of Gaming GROPOS Amateur Press Association Wild Hunt, The Anoch Game Systems Mystick Premium Card Game Apex Publications Shattered Dreams Apophis Consortium Obsidian Arc Dream Publishing Godlike Archangel Entertainment Extreme Vengeance Groo: The Game RPG's, Art Books, Miscellaneous Steve Stone's Zero RPG Arduin Grimoire Arduin Grimoire Armory, The Fantasy Supplements Associates International Game News Atlas Games Ars Magica Cyberpunk (Atlas Games) Feng Shui Furry Pirates On the Edge Over the Edge Pandemonium Rune Underground Unknown Armies Atomic Hyrax Games Purgatory RPG Avalon Hill Heroes Magazine Lords of Creation Runequest Tales from the Floating Vagabond Aztech Power, The Backstage Press Theatrix Bad Dog Publications Fluffy Quest Balboa Game Co. Role Playing Supplements Ballantine Books Dragonlover's Guide to Pern, The Fantasy Novels Lord of the Rings, The, Filmbook Robotech Novels Shannara Novels Star Wars Novels Xanth Novels Bantam Books Fantasy Novels Game of Thrones Novels Star Wars Novels Bard Games Fantasy Supplements Talislanta Baron Publishing Company Gryphon Basement Games Unlimited, LLC Forge Out of Chaos RPG Bayonet Games Pellinen Islands, The BBRack Productions Promised Sands Berkeley Books Elric Novels Novels Biohazard Games Blue Planet Bioware Corp. Baldur's Gate Black Dragon Press, The Darkurthe Legends Dragon Storm Black Gate Publishing Legacy RPG Black Knight Games Fantasy Legend Board Enterprises LegendQuest Board-Craft Simulations Inc. -

THE SCIENTIFIC ROMANCE ROLE PLAYING GAME by Marcus L

FFoorrggootttteenn FFuuttuurreess TThhee SScciieennttiiffiicc RRoommaannccee RRoollee PPllaayyiinngg GGaammee BByy MMaarrccuuss LL.. RRoowwllaanndd FFoorrggootttteenn FFuuttuurreess THE SCIENTIFIC ROMANCE ROLE PLAYING GAME By Marcus L. Rowland Copyright © 2006, portions Copyright © 1993-2006 This document is copyright, but you are encouraged to make copies and print-outs as needed. You may make modifications for your own use, but modified versions MUST NOT be distributed. Art comes from a variety of copyright-expired sources, or has been created by the author. Larger versions of most pictures can be found on the Forgotten Futures CD-ROM or on line as part of the resources available for this game. This PDF has been published as a free download – if you are asked to pay for it please contact the author! Introduction 1 Role Playing 38 About This Release 1 Running Adventures 39 Example of Play 2 Setting The Scene 39 Game Requirements 4 Plot 41 Game Terms 4 Non-Player Characters 43 Acknowledgements 5 Props 47 Characters And Rules 6 Game Worlds 49 Character Record 7 The Real World 51 Character Points 8 Currency, Wages and Prices 51 Equipment and Notes, Weapons, etc. 10 Timeline 1890-1914 54 Characteristics 12 World Leaders 1890-1914 56 Using Characteristics 12 Improving The Odds 14 Common Characteristics Rolls 15 APPENDIX - Units and Dates 57 Skills 15 APPENDIX - Children and Animals 58 Using Skills 16 Children as Adventurers 58 Temporary Skills 17 Dogs as Adventurers 59 Projects 17 APPENDIX - Adding Melodrama 60 Improving Skills 18 Heroes 61 Adding Skills 18 Anti-Heroes 63 Free Skills 20 Romantic Leads 64 Skill list 20 Villains 66 Wounds 23 Everybody Else 70 Medical Skills, Recovery, and Death 24 Acting the Part 74 Combat 25 APPENDIX - It's a Kind of MAGIC.. -

Polyhedron Index 001-118.Pdf

RPGA® Network POLYHEDRON® Newszine Index For Issues 1 through 118 Including the Introductory Issue [A] Created by Todd "Vand" Vanderbeek For use by the Members of the RPGA Network Updated Every Issue Aaron Gregory "Wolf" Stanton (from "Modern Day Warriors" in Counterfeit Dreams 50 "New Rouges Gallery") 42 Crisis in the Cragmoors 63 ABCs of Acronyms, The 53 The Darkcrypt (Ravager, Part 1) 30 Ability Scores: Downunder the Living City 77 Go West, Young Gamer (Boot Hill) 13 Easy Money 55 Absorbtion (new spell from "Unofficial New Magic-User Spells, The Enemy of My Enemy (Dark Sun) 99 Part 2") 25 Escape from Demoncoomb Mountain 38 Ace Against Odds: the Solitaire Scenario, An by Mike Carr Experience Preferred, Part 1 72 (Dawn Patrol) 6 Experience Preferred, Part 2 73 Ace the Mutant Mouse (from "The Sewer Rats" in "New Rouges Experience Preferred, Part 3 74 Gallery") 45 Eye of the Leviathan (Living City) 87 Acid Arrows, +1 by Costa Valhouli (from "Radiating Magic") 47 Felicide Decreed (Cataclysm, Part 1) 48 Acid Ejector by James M. Ward (from "Weapons of the A Fluffy Wonderland 78 Ancients" - Gamma World) 6 A Friend in Need 59 Adagio Jones and The Goodwinds (New Rouges Gallery) 54 Ghost Righters A Adaptation (new spell from "Unofficial New Spells for Clerics") 22 The Great Bugbear Hunt 28 Adding to the Anvil by Jason Rock (non-weapon proficiencies) 79 Guarded Wagon (Dark Sun) 80 Adhesion (new spell from "Unofficial New Magic-User Spells") 24 A Handful of Dust (Living City) 98 ADVANCED DUNGEONS & DRAGONS Hero 68 (See Also: Notes for the Dungeon -

Dragon Magazine #201

Issue #201 Vol. XVIII, No. 7 January 1994 SPECIAL ATTRACTIONS Publisher TSR, Inc. Fantasy Cities Never Sleep 9 Explore urban opportunities for magic and mayhem. Associate Publisher Brian Thomsen 10The City of Lofty Pillars Steve Kurtz Editor-in-Chief Can you find the lost city of the AL-QADIM® setting? Kim Mohan Turkeys Underground Cities Allen Varney Associate editor Read about Allens Amazing Adventure; learn about Dale A. Donovan 16 these real-world dungeons. Fiction editor Barbara G. Young The Evolution of a Castle Thomas Reid 24Building a castle requires more than a pencil and Editorial assistant graph paper. Wolfgang H. Baur Seven Steps to a Successful Castle Art director Larry W. Smith L. Richard Baker III 33Use these expanded castle-construction rules to build Production staff your PCs ultimate abode. Tracey Isler Angelika Lokotz Subscriptions Janet L. Winters FICTION U.S. advertising Cindy Rick The River Children Peni R. Griffin 88Three lost children are the key to entering the afterworld. U.K. correspondent and U.K. advertising Wendy Mottaz Editorial Contributions Janis Wells Lisa Neuberger DRAGON® Magazine (ISSN 0279-6848) is publishedtion throughout the United Kingdom is by Comag monthly by TSR, Inc., P.O. Box 756 (201 Sheridan Magazine Marketing, Tavistock Road, West Drayton, Springs Road), Lake Geneva WI 53147, United States Middlesex UB7 7QE, United Kingdom; telephone: of America. The postal address for all materials from 0895-444055. the United States of America and Canada except Subscriptions: Subscription rates via second-class subscription orders is: DRAGON® Magazine, P.O. Box mail are as follows: $30 in U.S. -

August 26 2016 This Is a Compilation of the Last 33 Pdf Share Threads and the Rpg Generals Threads

Da Archive August 26 2016 This is a compilation of the last 33 pdf share threads and the rpg generals threads. A HUGE THANK YOU to all contributors. It has been cleaned up some, labeled poorly, and shuffled about a little to perhaps be more useful. There are links to perhaps 16,000 pdfs. Don't be intimidated, some are duplicates. Go get a coffee and browse. As Anon says; “Surely in Da Archive™ somewhere.” Part I is the Personal Collections. They are Huge. You need to go to each one and look at them. They often have over 1000 links each. Note: Some of the very nice Collections hosted on Mega have expired. If the O.P.s redo them, please post links in the PDF Share threads. Part II is the Alphabetical Section. Well.... when I say “alphabetical”, I really mean artistically arranged according to my whim. Please buy a copy of a book if you use it. No really, I mean it. The Negarons generated by struggling game publishers have been proven to psychically attach themselves to the dice of gamers who like a game enough to play it but not enough to support it. - - – - - – - - - – - - - - - --- – --- --- – - - - - - - - - - - – - - – - - - - - - – - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - – - - – - - - – - - - - - --- – --- --- – - - - - - - - - - - – - - – - - - - - - – - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Mixed Personal Big Collections – most have HUNDREDS of files These Are The LOTSASTUFF FILES --- – Tons & Tons & Tons o' goodies! LOTSASTUFF 's Awesome Reference Resources. City Builder, Magical Society, Historical Costumes, Name -

Dragon Magazine #221

_./ Issue #221 Vol. XX, No. 4 September 1995 Publisher SPECIAL ATTRACTIONS TSR, Inc. In Dreams-Dave Gross Associate Publisher 10 Venture beyond the walls of sleep, into the land of Brian Thomsen the dream wizards. Editor Magic of Kings, Magic of the Land-Kevin Melka Wolfgang Baur 16 Potent magic comes from a mage-king’s connection to the Associate editor land he rules. Dave Gross 20 The Little Wish-Jon Winter Fiction editor Is a cantrip magical garbage or an overlooked treasure? Uses for Barbara Young the apprentice’s favorite (and only) spell. Ley of the Land-Carrie Bebris, Anne Brown, and Ed Stark Art director 24 Larry Smith To master the greatest magic, a wizard regent needs conduits of magical power. Editorial assistant Michelle Vuckovich Production Staff REVIEWS Tracey Isler Role-playing Reviews-Rick Swan Subscriptions 42 Ricks wades in to do battle with a horde of new combat rulebooks, Janet L. Winters including the AD&D® game’s new optional Combat & Tactics volume. U.S. advertising Eye of the Monitor-Jay and Dee and JB Cindy Rick 115 The scoop on High Seas Trader, Hammer of the Gods, U.K. correspondent and Toh Shin Den. and U.K. advertising The Role of Books-John Bunnell Carolyn Wildman 49 New fantasy novels, Star Trek, and the Magic: The Gathering anthology. DRAGON® Magazine (ISSN 0279-6848) is published kingdom is by Comag Magazine Marketing, Tavistock monthly by TSR, Inc., 201 Sheridan Springs Road, Road, West Drayton, Middlesex, UB7 7QE, United Lake Geneva, WI 53147, United States of America.