Competition with Constraints: Challenges Facing Medicare Reform

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2013-14 Catalogue

1 Contents Academic Calendar .................................................................................................................2 General Information ...............................................................................................................5 A History of Vassar College ....................................................................................................5 Learning and Living at Vassar .................................................................................................6 Admission ..............................................................................................................................12 Fees .........................................................................................................................................15 Financial Aid .........................................................................................................................17 Alumnae and Alumni of Vassar College (AAVC) ...............................................................23 Academic Information ..........................................................................................................24 Degrees and Courses of Study ................................................................................................24 Preparation for Graduate Study .............................................................................................35 Instruction 2013/14 ...............................................................................................................36 -

Implications of Empirical Evidence in Other Markets for the Health Sector

Does Price Transparency Improve Market Efficiency? Implications of Empirical Evidence in Other Markets for the Health Sector Updated April 29, 2008 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov RL34101 Does Price Transparency Improve Market Efficiency? Implications of Empirical Evidence in Other Markets for the Health Sector Summary Consumer advocates, proponents of wider use of market incentives in the health care sector, and some policy makers have called for greater price transparency. These measures might include posting prices in an accessible form or regulations constraining price discrimination (different prices charged to different customers). Price transparency implies that consumers can obtain price information easily, so they can usefully compare costs of different choices. Price transparency may also mean consumers understand how prices are set and are aware of price discrimination. In health care markets consumers often have difficulty finding useful price data. In particular, few consumers have a clear idea of what hospital stays or hospital-based procedures will cost, or understand how hospital charges are determined. Many empirical studies have investigated how changes in price transparency have affected various markets. Most of this evidence, largely relating to advertising restrictions and lower search costs on the Internet, suggests that price transparency leads to lower and more uniform prices, a view consistent with predictions of standard economic theory. If this evidence could be applied to the health market, it would suggest that reforms that increase transparency would reduce prices. In cases involving NASDAQ and Amazon.com, public reaction created pressure to change pricing strategies. A few studies, involving intermediate goods in one case and less clearly identified advertising effects in others, found that transparency raised prices. -

Merlis, Mark (B

Merlis, Mark (b. 1950) by Raymond-Jean Frontain Mark Merlis. Encyclopedia Copyright © 2015, glbtq, Inc. Courtesy Mark Merlis, www.markmerlis.com. Entry Copyright © 2006 glbtq, Inc. Reprinted from http://www.glbtq.com Mark Merlis is a novelist of unusual imaginative and linguistic power who examines contemporary gay concerns through the filter of historical parallels. His thought-filled, lyrical, yet wryly humorous narratives shift between the past and the present in order to illuminate the cause-and-effect relationship between homophobia and gay self-loathing, among other issues. Ultimately, his explorations of gay memory and the gay past offer a vision of how the cycles of violence can be broken and individuals join hands across the divides that separate them. In American Studies (1994), Reeve, the elderly victim of a brutal beating by a hustler he brought home late one night, spends his time while recuperating in the hospital recollecting how Tom Slater, his college mentor, was driven to commit suicide when outed during the McCarthy era. In An Arrow's Flight (1998), Merlis sets the events of the Trojan War in a late twentieth-century Mediterranean or Caribbean milieu, adapting the ancient myth of Philoctetes--who was abandoned under miserable circumstances by his fellow Greeks en route to Troy when a leg wound festered so badly that no one could bear its rank odor--to illuminate American attitudes towards the gay body in general, and towards AIDS-sufferers in particular. And in Man about Town (2003), Joel Lingeman, a middle-aged civil servant specializing in health care issues who has just been abandoned by his longtime partner, searches for a bathing suit model about whose image in a magazine Joel fantasized as a youth. -

Rising Out-Of-Pocket Spending for Medical Care: a Growing Strain on Family Budgets

RISING OUT-OF-POCKET SPENDING FOR MEDICAL CARE: A GROWING STRAIN ON FAMILY BUDGETS Mark Merlis, Douglas Gould, and Bisundev Mahato February 2006 ABSTRACT: Since the late 1990s, accelerated growth in health care spending has translated into increased burdens on family budgets. In 2001–02, an average of 13 million families per year had direct out-of-pocket (OOP) costs equal to or exceeding 10 percent of family income. When premium costs are added into the equation, even more families are devoting a substantial share of resources to health care expenses. Using data from the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey to examine trends in family OOP spending between 1996–97 and 2001–02, this report examines the components of OOP spending and characteristics of families with high OOP costs, including income level and insurance coverage. Families struggling with high OOP expenses are more likely than other families to report difficulties in obtaining needed care, and often have trouble paying their bills—increasing the possibility that they may face debt or bankruptcy or drop coverage altogether. Support for this research was provided by The Commonwealth Fund. The views presented here are those of the authors and not necessarily those of The Commonwealth Fund or its directors, officers, or staff. This and other Fund publications are online at www.cmwf.org. To learn more about new publications when they become available, visit the Fund’s Web site and register to receive e-mail alerts. Commonwealth Fund pub. no. 887. CONTENTS List of Figures and Tables................................................................................................iv -

Volume 22 Issue 1.Pdf

CONNECTICUT INSURANCE LAW JOURNAL Volume 22, Number 1 Summer 2016 University of Connecticut School of Law Hartford, Connecticut Connecticut Insurance Law Journal (ISSN 1081-9436) is published at least twice a year by the Connecticut Insurance Law Journal Association at the University of Connecticut School of Law. Periodicals postage paid at Hartford, Connecticut. Known office of publication: 55 Elizabeth Street, Hartford, Connecticut 06105-2209. Printing location: Western Newspaper Publishing Company, 929 West 16th Street, Indianapolis, Indiana 46202. Please visit our website at http://www.insurancejournal.org or see the final page of this issue for subscription and back issue ordering information. Postmaster: Send address changes to Connecticut Insurance Law Journal, 55 Elizabeth Street, Hartford, Connecticut 06105-2209. The Journal welcomes the submission of articles and book reviews. Both text and notes should be double or triple-spaced. Submissions in electronic form are encouraged, and should be in Microsoft™ Word™ version 97 format or higher. Citations should conform to the most recent edition of A UNIFORM SYSTEM OF CITATION, published by the Harvard Law Review Association. It is the policy of the University of Connecticut to prohibit discrimination in education, employment, and in the provision of services on the basis of race, religion, sex, age, marital status, national origin, ancestry, sexual preference, status as a disabled veteran or veteran of the Vietnam Era, physical or mental disability, or record of such impairments, or mental retardation. University policy also prohibits discrimination in employment on the basis of a criminal record that is not related to the position being sought; and supports all state and federal civil rights statutes whether or not specifically cited within this statement. -

The Return of Ulysses ‘Only Edith Hall Could Have Written This Richly Engaging and Distinctive Book

the return of ulysses ‘Only Edith Hall could have written this richly engaging and distinctive book. She covers a breathtaking range of material, from the highest of high culture to the camp, cartoonish, and frankly weird; from Europe to the USA to Africa and the Far East; and from literature to film and opera. Throughout this tour of the huge variety of responses that there have been to the Odyssey, a powerful argument emerges about the appeal and longevity of the text which reveals all the critical and political flair that we have come to expect of this author. It is all conveyed with the infectious excitement and clarity of a brilliant performer. The Return of Ulysses represents a major contribution to how we assess the continuing influence of Homer in modern culture.’ — Simon Goldhill, Professor of Greek Literature and Culture, University of Cambridge ‘Edith Hall has written a book many have long been waiting for, a smart, sophisticated, and hugely entertaining cultural history of Homer’s Odyssey spanning nearly three millennia of its reception and influence within world culture. A marvel of collection, association, and analysis, the book yields new discoveries on every page. In no other treatment of the enduring figure of Odysseus does Dante rub shoulders with Dr Who, Adorno and Bakhtin with John Ford and Clint Eastwood. Hall is superb at digging into the depths of the Odyssean character to find what makes the polytropic Greek so internationally indestructible. A great delight to read, the book is lucid, appealingly written, fast, funny, and full of enlightening details. -

Can Competition Improve Medicare?: a Look At

QUALITY ACCOUNTABILITY UNIVERSAL COVERAGE GUARANTEED ACCESS RISK ADJUSTMENT COST CONTROL BENEFICIARIES INFORMED CHOICE STANDARD COMPREHENSIVE BENEFITS QUALITY ACCOUNTABILITY UNIVERSAL COVERAGE GUARANTEED ACCESS RISK ADJUSTMENT COST CONTROL INFORMED CHOICE PRIVATE INSURANCE PLANS STANDARD COMPREHENSIVE BENEFITS QUALITY ACCOUNTABILITY UNIVERSAL COVERAGE GUARANTEED ACCESS RISK ADJUSTMENT HEALTH CARE PROVIDERS COST CONTROL INFORMED CHOICE STANDARD COMPREHENSIVE BENEFITS QUALITY ACCOUNTABILITY UNIVERSAL COVERAGE GUARANTEED ACCESS RISK ADJUSTMENT COST CONTROL INFORMED CHOICE GOVERNMENT QUALITY UNIVERSAL COVERAGE GUARANTEED ACCESS RISK ADJUSTMENT COST CONTROL BENEFICIARIES INFORMED CHOICE STANDARD COMPREHENSIVE BENEFITS QUALITY ACCOUNTABILITY UNIVERSAL COVERAGE GUARANTEED ACCESS RISK ADJUSTMENT COST CONTROL INFORMED CHOICE PRIVATE INSURANCE PLANS STANDARD COMPREHENSIVE BENEFITS QUALITY ACCOUNTABILITY UNIVERSAL COVERAGE GUARANTEED ACCESS RISK ADJUSTMENT HEALTH CARE PROVIDERS COST CONTROL INFORMED CHOICE STANDARD COMPREHENSIVE BENEFITS QUALITY ACCOUNTABILITY UNIVERSAL COVERAGE GUARANTEED ACCESS RISK ADJUSTMENT COST CONTROL GOVERNMENT STANDARD COMPREHENSIVE BENEFITS QUALITY ACCOUNTABILITY UNIVERSAL COVERAGE GUARANTEED ACCESS RISK ADJUSTMENTCan Competition COST CONTROL INFORMED CHOICEImprove STANDARD COMPREHENSIVE Medicare? BENEFITS QUALITY ACCOUNTABILITYA Look UNIVERSAL at Premium COVERAGE GUARANTEED Support ACCESS RISK ADJUSTMENT COST CONTROL INFORMED CHOICE STANDARD COMPREHENSIVE BENEFITS QUALITY ACCOUNTABILITY UNIVERSAL COVERAGE GUARANTEED ACCESS -

Aids: Ah Overview of Issues

Order Code IB87150 AIDS: AH OVERVIEW OF ISSUES Updated March 21, 1988 by Judith A. Johnson and Pamela W. Smith, Coordinators Science Policy Research Division Congressional Research Service CONTMTS SUMMARY ISSUE DEFINITION BACKGROUND AND ANALYSIS introduction Pamela Smith and Judith Johnson Education and Risk Reduction Mark Merlis Public Health Measure Judith Johnson Health Care and Social Services Mark Merlis Legal Issues Nancy Jones State Laws and Regulations Ann Wolfe Labor Issues Gail McCaP lion International Problems and Response Lois McMugh Actions by the Reagan Administration Pamela Smith Congressional Actions Pamela Smith LEGISLATION FOR ADDITIONAL READING AIDS: AN OVERVIEW OF ISSUES Many medical experts consider AIDS to be the gravest public health threat of this century. Statistics on cases and deaths are already alarming, and are projected to worsen: the current U.S. count of over 56,000 cases and 31,000 deaths is predicted to rise to 270,000 cases and 179,000 deaths by 1991, while the worldwide total of AIDS cases, now estimated at between 100,000 and 150,000, may rise to between 500,000 and 3 million by 1991. Public policy issues concerning AIDS arise in a number of areas. Policy debates on educational efforts have focused on the explicitness and value content of AIDS information, the relative roles of Federal and Local controls, and the effectiveness of mass education versus efforts targeted at risk groups including drug users, minorities, and young people. Public health measures to control the spread of the disease have involved debates over the usefulness and scope of testing in the absence of a cure or vaccine, and over the utility of quarantine. -

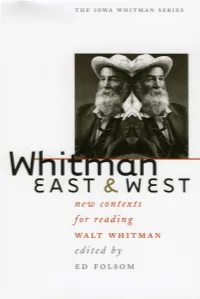

Gu Cheng and Walt Whitman

Whitman East & West the iowa whitman series Ed Folsom, series editor Whitman East & West New Contexts for Reading Walt Whitman edited by ed folsom university of iowa press iowa city University of Iowa Press, Iowa City 52242 Copyright © 2002 by the University of Iowa Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America http://www.uiowa.edu/uiowapress No part of this book may be reproduced or used in any form or by any means without permission in writing from the publisher. All reasonable steps have been taken to contact copyright holders of material used in this book. The publisher would be pleased to make suitable arrangements with any whom it has not been possible to reach. The publication of this book was generously supported by the University of Iowa Foundation. Printed on acid-free paper Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Whitman East and West: new contexts for reading Walt Whitman /edited by Ed Folsom. p. cm.—(The Iowa Whitman series) Includes bibliographical references and index. isbn 0-87745-821-9 (cloth) 1. Whitman, Walt, 1819–1892— Criticism and interpretation. 2. Whitman, Walt, 1819–1892— Appreciation—Asia. 3. Whitman, Walt, 1819–1892— Knowledge—Asia. 4. Books and reading—Asia. 5. Asia—In literature. I. Folsom, Ed, 1947–. II. Series. ps3238 .w46 2002 811Ј.3—dc21 2002021133 02 03 04 05 06 c 54321 for robert strassburg, who has put Whitman’s words to work in his music, his teaching, and his life. His performance of his Whitman compositions in Bejing literally set the tone for the “Whitman 2000” conference. -

May 15, 2015 | Volume XIII, Issue 1 the Hippo Set to Close and Comprehensive Car Care, a Long-Time Christmas, an Annu- by STEVE CHARING Staple on Eager Street

AN INDEPENDENT VOICE FOR THE LESBIAN, GAY, BISEXUAL, AND TRANSGENDER COMMUNITIES OUT May 15, 2015 | Volume XIII, Issue 1 The Hippo Set to Close and Comprehensive Car Care, a long-time Christmas, an annu- BY STEVE CHARING staple on Eager Street. al affair that benefits After 43 years, the Club Hippo, one of Bal- The Hippo, which opened on July 7, local non-profit orga- timores oldest and most iconic LGBT insti- 1972, possesses one of the largest dance nizations. The Hippo tutions, is poised to close its doors. floors of any club in the state. During dis- had also served as As confirmed at a meeting cos heyday, the Hippo flourished with the venue for Gay with employees on May 9, Hippo End of huge crowds dancing to the beats of Bingo a weekly owner Chuck Bowers has negoti- vintage and newer disco hits on its event whereby non- ated to convert the building at the an Era spacious rectangular floor bathed in profit organizations southwest corner of Charles and glimmering, colorful lights. As musical shared in the pro- Eager streets into a CVS store. tastes changed in succeeding years, so ceeds. To broaden The negotiations between CVS and did the music. The Hippo kept up. its appeal, the Hippo Bowers began early in 2014. Under the The club also features a popular video has held weekly Hip- arrangement Bowers will retain ownership bar where karaoke and weekly show tunes Hop nights the past of the building and lease it to CVS. There The Hippo video presentations occur and a saloon few years. -

Participant Bios

THE COMMONWEALTH FUND 2007 INTERNATIONAL SYMPOSIUM ON HEALTH CARE POLICY PARTICIPANT BIOGRAPHIES GERARD F. ANDERSON is a professor of health policy and management and professor of international health at the Johns Hopkins University Bloomberg School of Public Health, professor of medicine at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, director of the Johns Hopkins Center for Hospital Finance and Management, and co-director of the Johns Hopkins Program for Medical Technology and Practice Assessment. He recently stepped down as the national program director for the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation sponsored program “Partnership for Solutions: Better Lives for People with Chronic Conditions.” Anderson is currently conducting research on chronic conditions, comparative insurance systems in developing countries, medical education, health care payment reform, and technology diffusion. He has directed reviews of health systems for the World Bank and USAID in multiple countries. He has authored two books on health care payment policy, published over 200 peer-reviewed articles, testified in Congress over 35 times as an individual witness, and serves on multiple editorial committees. Prior to his arrival at Johns Hopkins, Anderson held various positions in the Office of the Secretary, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, where he helped to develop Medicare prospective payment legislation. PETER BACH, M.D., is associate attending physician at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center in New York and is board certified in internal medicine, pulmonary medicine and critical care medicine. He is a National Institutes of Health-funded researcher with expertise in quality of care and epidemiologic research methods. His research on health disparities, variations in healthcare quality, and lung cancer epidemiology has appeared in The New England Journal of Medicine, the Journal of the American Medical Association, and the Journal of the National Cancer Institute. -

The Gay & Lesbian Review

100 YEARS OF SUBTERFUGE The Gay& Lesbian Review WORLDWIDE Nov.–Dec. 2017 $5.95 USA and Canada Leonard Bernstein, Jerome Robbins, Arthur Laurents, and Stephen Sondheim ANDREW HOLLERAN A. E. Housman’s ‘Lads’ JEFFREY MEYERS Thomas Mann’s Secret Sharer DAVID LAFONTAINE Inside West Side Story SALMAN RUSHDIE ‘I Grew Up in Bombay, Home of the Hijra’ The Gay & Lesbian Re view November–December 2017 • VOLUME XXIV, NUMBER6 WORLDWIDE The Gay & Lesbian Review ® WORLDWIDE PO Box 180300, Boston, MA 02118 CONTENTS Editor-in-Chief and Founder 100 Years of Subterfuge RICHARD SCHNEIDER JR. ____________________________________ Literary Editor FEATURES MARTHA E. STONE “I grew up in Bombay, home of the Hijra.” 12 S ALMAN RUSHDIE Poetry Editor Frank Pizzoli talks with the author of The Golden House DAVID BERGMAN The Etymology of Lads 15 A NDREW HOLLERAN Associate Editors How A.E. Housman’s obsession with one lad became an archetype JIM FARLEY JEREMY FOX Thomas Mann’s Secret Sharer 19 J EFFREY MEYERS CHRISTOPHER HENNESSY It was his own son Klaus, a gay preteen with Tadzio possibilities MICHAEL SCHWARTZ Insi Contributing Writers de West Side Story 22 D AVID LAFONTAINE ROSEMARY BOOTH The four creators, all gay men, worked in a few winks and subtexts DANIEL BURR Picturing “The German V TEPHAN RICHARD CANNING ice” 26 S LIKOSKY COLIN CARMAN Postcards riffed on a national stereotype in a pre-WWI gay scandal ALFRED CORN ALLEN ELLENZWEIG A Priest’s Book Stirs the Faithful 30 D ONALD L. B OISVERT, CHRIS FREEMAN Two perspectives on James Martin, SJ’s Building a Bridge BRIAN BROMBERGER PHILIP GAMBONE MATTHEW HAYS ANDREW HOLLERAN REVIEWS CASSANDRA LANGER ANDREW LEAR John Lauritsen, ed.