COVID-19 and Animals in Captivity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Estimation of Antimicrobial Activities and Fatty Acid Composition Of

Estimation of antimicrobial activities and fatty acid composition of actinobacteria isolated from water surface of underground lakes from Badzheyskaya and Okhotnichya caves in Siberia Irina V. Voytsekhovskaya1,*, Denis V. Axenov-Gribanov1,2,*, Svetlana A. Murzina3, Svetlana N. Pekkoeva3, Eugeniy S. Protasov1, Stanislav V. Gamaiunov2 and Maxim A. Timofeyev1 1 Irkutsk State University, Irkutsk, Russia 2 Baikal Research Centre, Irkutsk, Russia 3 Institute of Biology of the Karelian Research Centre of the Russian Academy of Sciences, Petrozavodsk, Karelia, Russia * These authors contributed equally to this work. ABSTRACT Extreme and unusual ecosystems such as isolated ancient caves are considered as potential tools for the discovery of novel natural products with biological activities. Acti- nobacteria that inhabit these unusual ecosystems are examined as a promising source for the development of new drugs. In this study we focused on the preliminary estimation of fatty acid composition and antibacterial properties of culturable actinobacteria isolated from water surface of underground lakes located in Badzheyskaya and Okhotnichya caves in Siberia. Here we present isolation of 17 strains of actinobacteria that belong to the Streptomyces, Nocardia and Nocardiopsis genera. Using assays for antibacterial and antifungal activities, we found that a number of strains belonging to the genus Streptomyces isolated from Badzheyskaya cave demonstrated inhibition activity against Submitted 23 May 2018 bacteria and fungi. It was shown that representatives of the genera Nocardia and Accepted 24 September 2018 Nocardiopsis isolated from Okhotnichya cave did not demonstrate any tested antibiotic Published 25 October 2018 properties. However, despite the lack of antimicrobial and fungicidal activity of Corresponding author Nocardia extracts, those strains are specific in terms of their fatty acid spectrum. -

Reality Check of US Allegations Against China on COVID-19

Reality Check of US Allegations Against China on COVID-19 Reality Check of US Allegations Against China on COVID-19 Catalog 1.Allegation: COVID-19 is “Chinese virus” Reality Check: WHO has made it clear that the naming of a disease should not be associated with a particular country or place. 2.Allegation: Wuhan is the origin of the virus Reality Check: Being the first to report the virus does not mean that Wuhan is its origin. In fact, the origin is still not identified. Source tracing is a serious scientific matter, which should be based on science and should be studied by scientists and medical experts. 3.Allegation: The virus was constructed by the Wuhan Institute of Virology Reality Check: All available evidence shows that SARS-CoV-2 is natural in origin, not man-made. 4.Allegation: COVID-19 was caused by an accidental leak from the Wuhan Institute of Virology Reality Check: The Wuhan National Biosafety Laboratory (Wuhan P4 Laboratory) in the WIV is a government cooperation program between China and France. The Institute does not have the capability to design and synthesize a new coronavirus, and there is no evidence of pathogen leaks or staff infections in the Institute. 5.Allegation: China spread the virus to the world Reality Check: China took the most stringent measures within the shortest possible time, which has largely kept the virus within Wuhan. Statistics show that very few cases were exported from China. 6.Allegation: The Chinese contracted the virus while eating bats Reality Check: Bats are never part of the Chinese diet. -

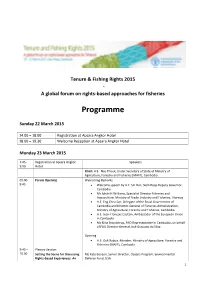

A Global Forum on Rights-Based Approaches for Fisheries

Tenure & Fishing Rights 2015 - A global forum on rights-based approaches for fisheries Programme Sunday 22 March 2015 14.00 – 18.00 Registration at Apsara Angkor Hotel 18.00 – 19.30 Welcome Reception at Apsara Angkor Hotel Monday 23 March 2015 7:45- Registration at Apsara Angkor Speakers 9:00 Hotel Chair: H.E. Nao Thuok, Under Secretary of State of Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries (MAFF), Cambodia 09:00- Forum Opening Welcoming Remarks 9:45 Welcome speech by H.E. Sin Run, Siem Reap Deputy Governor, Cambodia Mr Johán H Williams, Specialist Director Fisheries and Aquaculture, Ministry of Trade, Industry and Fisheries, Norway H.E. Eng Chea San, Delegate of the Royal Government of Cambodia and Director-General of Fisheries Administration, Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries, Cambodia H.E. Jean-François Cautain, Ambassador of the European Union in Cambodia Ms Nina Brandstrup, FAO Representative in Cambodia, on behalf of FAO Director-General José Graziano da Silva Opening H.E. Ouk Rabun, Minister, Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries (MAFF), Cambodia 9:45 – Plenary Session: 10.30 Setting the Scene for Discussing Ms Kate Bonzon, Senior Director, Oceans Program, Environmental Rights-based Experiences: An Defense Fund, USA 1 overview An overview of the types of user rights and how they may conserve fishery resources and provide food security, contribute to poverty eradication, and lead to development of fishing communities. 10.30- Plenary: Question and Answer 11:00 session Moderator: Mr Georges Dehoux, Attaché, Cooperation Section, Delegation of the European Union in the Kingdom of Cambodia and Co- Chair of the Cambodia Technical Working Group on Fisheries 11:00- Plenary session: Cambodia’s Ms Kaing Khim, Deputy Director General, Fisheries Administration, 11:30 experience with rights-based Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries, Cambodia approaches: the social, economic and environmental aspects of developing and implementing a user rights system 11:30- Plenary session: A[nother] Asian Mr Dedi S. -

People Can Catch Diseases from Their Pets

People Can Catch Diseases from Their Pets [Announcer] This program is presented by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [Tracey Hodges] Hello, I’m Tracey Hodges and today I’m talking with Dr. Carol Rubin, Associate Director for Zoonoses and One Health at CDC. Our conversation is based on her article about zoonotic diseases in our pets, which appears in CDC's journal, Emerging Infectious Diseases. Welcome, Dr. Rubin. [Carol Rubin] Thanks, Tracey. I’m pleased to be here. [Tracey Hodges] Dr. Rubin, tell us about One Health. [Carol Rubin] Well, One Health is a concept that takes into account the relationship among human health and animal health and the environment. One Health recognizes that the three sectors, that is, people, animals, and the environment, are closely connected to each other, and that movement of diseases from animals to humans can be influenced by changes in the environment they share. However, because there’s no strict definition for One Health, the phrase ‘One Health’ can mean different things to different people. Some people think of One Health as a return to simpler times when most physicians were generalists rather than specialists, and physicians and veterinarians communicated regularly. However, other people think that the One Health is especially important now because we live in a time when there is an increase in the number of new diseases that affect human health. Diseases that pass between people and animals are called zoonoses. And recently, researchers have determined that more than 70 percent of emerging infectious diseases in people actually come from animals. -

Career Guide Cover.Indd

Food Law and Policy Career Guide For anyone interested in an internship or a career in food law and policy, this guide illustrates many of the diverse array of choices, whether you seek a traditional legal job or would like to get involved in research, advocacy, or policy-making within the food system. 2nd Edition Summer 2013 Researched and Prepared by: Harvard Food Law and Policy Clinic Emily Broad Leib, Director Allli Condra, Clinical Fellow Harvard Food Law and Policy Division Center for Health Law and Policy Innovation Harvard Law School 122 Boylston Street Jamaica Plain, MA 02130 [email protected] www.law.harvard.edu/academics/clinical/lsc Harvard Food Law Society Cristina Almendarez, Grant Barbosa, Rachel Clark, Kate Schmidt, Erin Schwartz, Lauren Sidner Harvard Law School www3.law.harvard.edu/orgs/foodlaw/ Special Thanks to: Louisa Denison Kathleen Eutsler Caitlin Foley Adam Jaffee Annika Nielsen Kate Olender Niousha Rahbar Adam Soliman Note to Readers: This guide is a work in progress and will be updated, corrected, and expanded over time. If you want to include additional organizations or suggest edits to any of the current listings, please email [email protected]. 2 table of contents an introduction to food law and policy ........................................................................................................................... 4 guide to areas of specialization .......................................................................................................................................... 5 section -

Felicia Wu, Ph.D

FELICIA WU, PH.D. John A. Hannah Distinguished Professor Department of Food Science and Human Nutrition Department of Agricultural, Food, and Resource Economics Michigan State University 204 Trout FSHN Building, 469 Wilson Rd, East Lansing, MI 48824 Tel: 1-517-432-4442 Fax: 1-517-353-8963 [email protected] EDUCATION 1998 Harvard University A.B., S.M., Applied Mathematics & Medical Sciences 2002 Carnegie Mellon University Ph.D., Engineering & Public Policy APPOINTMENTS & POSITIONS 2013-present John A. Hannah Distinguished Professor, Department of Food Science and Human Nutrition, Department of Agricultural, Food, and Resource Economics, Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI . Director, Center for Health Impacts of Agriculture (CHIA) . Core Faculty, Center for Integrative Toxicology . Core Faculty, International Institute of Health . Core Faculty, Center for Gender in Global Context 2011-2013 Associate Professor, Department of Environmental and Occupational Health, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA . Secondary Faculty, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine . Secondary Faculty, Graduate School of Public and International Affairs . Core Faculty, Center for Research on Health Care . Secondary Faculty, Center for Bioethics and Health Law . Faculty Advisory Board, European Union Center for Excellence 2004-2011 Assistant Professor, Department of Environmental and Occupational Health, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA 2002-2004 Associate Policy Researcher, RAND, Pittsburgh, PA RESEARCH AND TEACHING Fields Food Safety, Food Security, Global Health and the Environment, Mycotoxins, Agricultural Health, Agricultural Biotechnology, Climate Change, Indoor Air Quality Methods Economics, Mathematical Modeling, Quantitative Risk Assessment, Risk Communication, Policy Analysis AWARDS & HONORS . The National Academies: National Research Council (NRC) Committee on Considerations for the Future of Animal Science Research, 2014-2015 . -

Spillback in the Anthropocene: the Risk of Human-To-Wildlife Pathogen Transmission for Conservation and Public Health

Spillback in the Anthropocene: the risk of human-to-wildlife pathogen transmission for conservation and public health Anna C. Fagre*1, Lily E. Cohen2, Evan A. Eskew3, Max Farrell4, Emma Glennon5, Maxwell B. Joseph6, Hannah K. Frank7, Sadie Ryan8, 9,10, Colin J Carlson11,12, Gregory F Albery*13 *Corresponding authors: [email protected]; [email protected] 1: Department of Microbiology, Immunology, and Pathology, College of Veterinary Medicine and Biomedical Sciences, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, CO 2: Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, NY 10029 3: Department of Biology, Pacific Lutheran University, Tacoma, WA, 98447 USA 4: Department of Ecology & Evolutionary Biology, University of Toronto 5: Disease Dynamics Unit, Department of Veterinary Medicine, University of Cambridge, Cambridge CB3 0ES, UK 6: Earth Lab, University of Colorado Boulder, Boulder, CO 80309 7: Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, Tulane University, New Orleans, LA, 70118 USA 8: Quantitative Disease Ecology and Conservation (QDEC) Lab Group, Department of Geography, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL, 32610 USA 9: Emerging Pathogens Institute, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL, 32610 USA 10: School of Life Sciences, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban, 4041, South Africa 11: Center for Global Health Science and Security, Georgetown University Medical Center, Washington, DC, 20057 USA 12: Department of Microbiology and Immunology, Georgetown University Medical Center, Washington, DC, 20057 USA 13: Department of Biology, Georgetown University, Washington, DC, 20057 USA 1 Abstract The SARS-CoV-2 pandemic has led to increased concern over transmission of pathogens from humans to animals (“spillback”) and its potential to threaten conservation and public health. -

What If California's Drought Continues?

August 2015 PPIC WATER POLICY CENTER What If California’s Drought Continues? Ellen Hanak Jeffrey Mount Caitrin Chappelle Jay Lund Josué Medellín-Azuara Peter Moyle Nathaniel Seavy Research support from Emma Freeman, Jelena Jedzimirovic, Henry McCann, and Adam Soliman Supported with funding from the California Water Foundation, an initiative of the Resources Legacy Fund Summary California is in the fourth year of a severe, hot drought—the kind that is increasingly likely as the climate warms. Although no sector has been untouched, impacts so far have varied greatly, reflecting different levels of drought preparedness. Urban areas are in the best shape, thanks to sustained investments in diversified water portfolios and conservation. Farmers are more vulnerable, but they are also adapting. The greatest vulnerabilities are in some low-income rural communities where wells are running dry and in California’s wetlands, rivers, and forests, where the state’s iconic biodiversity is under extreme threat. Two to three more years of drought will increase challenges in all areas and require continued—and likely increasingly difficult—adaptations. Emergency programs will need to be significantly expanded to get drinking water to rural residents and to prevent major losses of waterbirds and extinctions of numerous native fish species, including most salmon runs. California also needs to start a longer-term effort to build drought resilience in the most vulnerable areas. Introduction In 2015, California entered the fourth year of a severe drought. Although droughts are a regular feature of the state’s climate, the current drought is unique in modern history. Taken together, the past four years have been the driest since record keeping began in the late 1800s.1 This drought has also been exceptionally warm (Figure 1). -

Evidence Along a Rural-Urban Transect in Viet Nam

agriculture Article Interactions between Food Environment and (Un)healthy Consumption: Evidence along a Rural-Urban Transect in Viet Nam Trang Nguyen 1,* , Huong Pham Thi Mai 2, Marrit van den Berg 1, Tuyen Huynh Thi Thanh 2 and Christophe Béné 3 1 Development Economics Group, Wageningen University & Research, 6700 HB Wageningen, The Netherlands; [email protected] 2 International Center for Tropical Agriculture (CIAT), Asia Office, Hanoi 100000, Vietnam; [email protected] (H.P.T.M.); [email protected] (T.H.T.T.) 3 International Center for Tropical Agriculture (CIAT), Cali 763537, Colombia; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: There is limited evidence on food environment in low and middle-income countries (LMICs) and the application of food environment frameworks and associated metrics in such settings. Our study examines how food environment varies across an urban-peri-urban-rural gradient from three sites in North Viet Nam and its relationship with child undernutrition status and household consumption of processed food. By comparing three food environments, we present a picture of the food environment in a typical emerging economy with specific features such as non-market food sources (own production and food transfers) and dominance of the informal retail sector. We combined quantitative data (static geospatial data at neighborhood level and household survey) and Citation: Nguyen, T.; Pham Thi Mai, qualitative data (in-depth interviews with shoppers). We found that across the three study sites, H.; van den Berg, M.; Huynh Thi traditional open and street markets remain the most important outlets for respondents. Contrary to Thanh, T.; Béné, C. -

Liquid Business

Florida State University Law Review Volume 47 Issue 1 In Tribute to Talbot "Sandy" D'Alemberte Article 9 Fall 2019 Liquid Business Vanessa C. Perez Texas A&M School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.law.fsu.edu/lr Part of the Business Organizations Law Commons Recommended Citation Vanessa C. Perez, Liquid Business, 47 Fla. St. U. L. Rev. 201 (2019) . https://ir.law.fsu.edu/lr/vol47/iss1/9 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Florida State University Law Review by an authorized editor of Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LIQUID BUSINESS VANESSA CASADO PEREZ* Water is scarcer due to climate change and in higher demand due to population growth than ever before. As if these stressors were not concerning enough, corporate investors are participating in water mar- kets in ways that sidestep U.S. water law doctrine’s aims of preventing speculation and assuring that the holders of water rights internalize any externalities associated with changes in their rights. The operation of these new players in the shadow of traditional water law is produc- ing elements of inefficiency and unfairness in the allocation of water rights. Resisting the polar calls for unfettered water markets, or, con- trarily, the complete de-commodification of water in the face of these challenges, this Article identifies a portfolio of measures that can help get regulated water markets back on a prudent, sustainable track in our contemporary world. -

Elephant Tuberculosis As a Reverse Zoonosis Postcolonial Scenes of Compassion, Conservation, and Public Health in Laos and France

ARTICLES Elephant tuberculosis as a reverse zoonosis Postcolonial scenes of compassion, conservation, and public health in Laos and France Nicolas Lainé Abstract In the last twenty years, a growing number of captive elephants have tested positive for tuberculosis (TB) in various institutions worldwide, causing public health concerns. This article discusses two localities where this concern has produced significant mobilizations to ask about the postcolonial resonances of this global response. The first case focuses on epidemiological studies of elephant TB in Laos launched by international organizations involved in conservation, and on the role of traditional elephant workers (mahouts) in the daily care for elephants. The second describes the finding by veterinarians of two elephants suspected of TB infection in a French zoo and the mobilization of animal rights activists against the euthanasia of the pachyderms. The article shows that while, in the recent past, in France elephants were considered markers of exoticism and in Laos as coworkers in the timber industry, they are now considered to be endangered subjects in need of care, compassion, and conservation. This analysis contributes to the anthropology of relations between humans and elephants through the study of a rare but fascinating zoonosis. Keywords tuberculosis, reverse zoonosis, Laos, France, elephant Medicine Anthropology Theory 5 (3): 157–176; http://doi.org/10.17157/mat.5.3.379. © Nicolas Lainé, 2018. Published under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license. 158 Elephant tuberculosis as a reverse zoonosis The re-emergence of a reverse zoonosis During the last twenty years, the growing number of captive elephants that have tested positive for tuberculosis (TB) in various institutions worldwide has caused public health concerns. -

Graduate Student Directory

Operations Research Center Massachusetts Institute of Technology GRADUATE STUDENT DIRECTORY November 2020 Moïse Blanchard Operations Research Center 275 Medford Street Massachusetts Institute of Technology Somerville, 02143 77 Massachusetts Avenue, E40-103 530-302-6432; +33 7 68 83 69 35 Cambridge, MA 02139 Email: [email protected] Education Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA Candidate for PhD in Operations Research; expected completion, May 2023. GPA: 4.0 Advisors: Professor Patrick Jaillet and Professor Alexandre Jacquillat Ecole Polytechnique, Palaiseau, France MS and BS in Applied Mathematics, completion July 2019. GPA: 4.0 Valedictorian Prépa at Lycée Louis-le-Grand, Paris, France Mathematics, Computer Science and Physics, completion July 2016. Prépa is selective post-secondary scientific studies leading to the Grandes Ecoles. Work Experience 2018 BNP Paribas Cardif, Lima, Peru Actuarial Intern Pricing and technical studies intern in the Actuarial Area. Classification automatization. 2016-2017 French Foreign Legion, Mayotte, France Land forces officer (Lieutenant) at Détachement de Légion Etrangère de Mayotte Group leader, operational and tactical instructor for malgach soldiers, and coordinator for operations against illegal immigration. Research Experience 2019–Present Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA Research Assistant Advisors: Professor Patrick Jaillet and Professor Alexandre Jacquillat Optimization under uncertainty on combinatorial problems including optimal matchings, TSP and other routing