The Negative Mirror and Critical Memory

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MIRROR MIRROR the Mind’S Mirror FILMS Seaglass 4 Restaurant 5 Outdoor Exhibits with Zarinah Agnew 7:30 P.M

AFTER DARK AFTER DARK SCHEDULE MAP PRESENTATIONS ACTIVITIES Upper Level Bay Observatory Gallery and Terrace 6 Observing Landscapes Mirrors in Technology and Art Through the Looking Glass Mirrors in Technology and Art With Sebastian Martin With the Explainers 6 With Sebastian Martin 6:30–8:30 p.m. | Bay Observatory Gallery 6:30–9:30 p.m. | Central Gallery 6:30–8:30 p.m. THURSDAY, OCTOBER 1, 2015 A Reflection on Mirrors Light Boxes and Anamorphic Mirrors The History of Mirrors 6:00—10:00 P.M. With Ron Hipschman With Explorables With Massimo Mazzotti 7:00 and 9:00 p.m. 7:00–10:00 p.m. | Central Gallery Main Level 8:30 p.m. Phyllis C. Wattis Webcast Studio BAR North Gallery MIRROR MIRROR The Mind’s Mirror FILMS SeaGlass 4 Restaurant 5 Outdoor Exhibits With Zarinah Agnew 7:30 p.m. | Kanbar Forum On Reflection East Gallery 9:00 p.m. | Kanbar Forum 4 Living Systems The History of Mirrors East With Massimo Mazzotti Corridor Contemplando la Ciudad (2005, 4 min.) Central Gallery 8:30 p.m. | Bay Observatory Gallery by Angela Reginato 5 3 Seeing & Listening Visions of a City (1978, 8 min.) by Lawrence Jordan A Reflection on Mirrors INSTALLATIONS BAR 3 With Ron Hipschman Suspended 2 (2005, 5 min.) by Amy Hicks Wattis 7:00 and 9:00 p.m. The Infinity Boxes Webcast Phyllis C. Wattis Webcast Studio Studio By Matt Elson Pier 15 (2013, 4 min.) by Michael Rudnick 6:00–10:00 p.m. | Central Gallery The Infinity Boxes By Matt Elson Visible Spectres 6:00–10:00 p.m. -

2000 Stainless Steels: an Introduction to Their Metallurgy and Corrosion

Dairy, Food and Environmental Sanitation, Vol. 20, No. 7, Pages 506-517 Copyright© International Association for Food Protection, 6200 Aurora Ave., Suite 200W, Des Moines, IA 50322 Stainless Steels: An Introduction to Their Metallurgy and Corrosion Resistance Roger A. Covert and Arthur H. Tuthill* and why they sometimes do not. In most cases, selection of the proper stainless steel leads to satisfactory performance. COMPOSITION, NOMEN- CLATURE AND GENERAL PROPERTIES Most metals are mixtures of a primary metallic element and one or more intentionally added other ele- This article has been peer-reviewed by two professionals. ments. These mixtures of elements are called alloys. Stainless steels are alloys, as are brasses (copper + zinc), bronzes (copper + tin), the many alu- INTRODUCTION better understanding of stainless minum alloys, and many other me- Worldwide, in industry, in busi- steels, especially to the non-metal- tallic materials. In general, solid ness and in the home, metals called lurgist. metals and alloys consist of randomly stainless steels are used daily. It is Industries are concerned with oriented grains that have a well-de- important to understand what these integrity of equipment and product fined crystalline structure, or lattice, materials are and why they behave purity. To achieve these, stainless within the grains. In stainless steels, the way they do. This is especially steels are often the economical and the crystalline structures within the true because the word “stainless” is practical materials of choice for pro- grains have been given names such as itself somewhat of a misnomer; these cess equipment. However, before ferrite, austenite, martensite, or a materials can stain and can corrode intelligent decisions can be made mixture of two or more of these. -

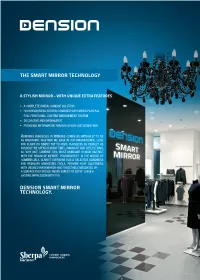

The Smart Mirror Technology

THE SMART MIRROR TECHNOLOGY A STYLISH MIRROR - WITH UNIQUE EXTRA FEATURES • A COMPLETE DIGITAL SIGNAGE SOLUTION • HIGH BRIGHTNESS SCREEN COMBINED WITH MEDIA PLAYER & FULL FUNCTIONAL CONTENT MANAGEMENT SYSTEM • DECORATIVE AND INFORMATIVE • PROVIDING INFORMATION THROUGH A NON-DISTURBING WAY ADMIRING OURSELVES IN MIRRORS COMES AS NATURALLY TO US AS BREATHING. WHETHER WE BASK IN OUR MAGNIFICENCE, LOOK FOR FLAWS OR SIMPLY TRY TO MAKE OURSELVES AS PERFECT AS POSSIBLE WE SPEND A MUCH TIME LOOKING AT OUR REFLECTIONS. SO WHY NOT COMBINE THIS MOST MUNDANE HUMAN INSTINCT WITH THE REALM OF INFINITE POSSIBILITIES? IN THE WORLD OF COMMERCIALS, ALMOST EVERYONE HAS A SELECTIVE BLINDNESS FOR ORDINARY MARKETING TOOLS. PROVIDE YOUR CUSTOMERS WITH DESIRED INFORMATION AND TARGETABLE MESSAGES ON A SURFACE THEY WOULD NEVER EXPECT TO GET IT. LEAVE A LASTING IMPRESSION WITH THE DENSION SMART MIRROR TECHNOLOGY. CONTENT & DEVICE MANAGEMENT THE MIRROR IS AVAILABLE IN FIVE DIFFERENT SIZES: MINI, SMALL, MEDIUM, LARGE, X-LARGE. CUSTOMERS MAY CHOOSE THE EXACT SIZE OF THE GLASS WITH A GIVEN SURFACE MAXIMUM. CUSTOMIZED MIRROR AND SCREEN COMBINATIONS ARE ALSO AVAILABLE IN HIGHER VOLUMES, PLEASE GET IN TOUCH TO DISCUSS. [email protected] FRONT VIEW MINI SMALL MEDIUM LARGE X-LARGE Display size (inch) 10 32 42 46 55 Display resolution HD Full HD Full HD Full HD Full HD Max Mirror Surface 0,9 0,9 2 2 (sqm) UPPER SIDE VIEW Minimum Width 250 870 1 100 1 180 1 380 (mm) Minimum Height 150 570 690 740 850 (mm) Depth (mm) 30 45 45 45 45 45 ° ANGLE REAR VIEW Weight (kg) 2 18 25-30 35-38 -

Art in the Mirror: Reflection in the Work of Rauschenberg, Richter, Graham and Smithson

ART IN THE MIRROR: REFLECTION IN THE WORK OF RAUSCHENBERG, RICHTER, GRAHAM AND SMITHSON DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Eileen R. Doyle, M.A. ***** The Ohio State University 2004 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor Stephen Melville, Advisor Professor Lisa Florman ______________________________ Professor Myroslava Mudrak Advisor History of Art Graduate Program Copyright by Eileen Reilly Doyle 2004 ii ABSTRACT This dissertation considers the proliferation of mirrors and reflective materials in art since the sixties through four case studies. By analyzing the mirrored and reflective work of Robert Rauschenberg, Gerhard Richter, Dan Graham and Robert Smithson within the context of the artists' larger oeuvre and also the theoretical and self-reflective writing that surrounds each artist’s work, the relationship between the wide use of industrially-produced materials and the French theory that dominated artistic discourse for the past thirty years becomes clear. Chapter 2 examines the work of Robert Rauschenberg, noting his early interest in engaging the viewer’s body in his work—a practice that became standard with the rise of Minimalism and after. Additionally, the theoretical writing the French phenomenologist Maurice Merleau-Ponty provides insight into the link between art as a mirroring practice and a physically engaged viewer. Chapter 3 considers the questions of medium and genre as they arose in the wake of Minimalism, using the mirrors and photo-based paintings of Gerhard Richter as its focus. It also addresses the particular way that Richter weaves the motifs and concerns of traditional painting into a rhetoric of the death of painting which strongly implicates the mirror, ultimately opening up Richter’s career to a psychoanalytic reading drawing its force from Jacques Lacan’s writing on the formation of the subject. -

Public Art Program OVERVIEW

Public Art Program OVERVIEW Artwork has been a critical component of the Phoenix Convention Center since it originally opened in 1972. Building upon this civic commitment to the arts, the City, through the Phoenix Office of Arts and Culture Public Art Program, commissioned new artworks by local, regional and national artists to be incorporated into the expanded Phoenix Convention Center. These works offer a variety of perspectives on life in Phoenix, the United States, and the world in the 21 st century, and join several other pieces in the Convention Center’s extensive collection. Public Art Program Budget and Funding: The art projects are funded through the City's Public Art Program. The program, established in 1986, has involved artists in the design of every kind of city building and space, ranging from streetscapes, freeway overpasses and pedestrian bridges, to canal trails, parks and libraries. The Phoenix Public Art Program is managed by the Phoenix Office of Arts and Culture and has commissioned more than 120 public art projects in the past 20 years. The Phoenix Convention Center’s $3.2 million public art budget comes from three capital improvement program bonds: • Phoenix Convention Center (Civic Plaza) Capital Improvement Percent for Art Funds • Street Transportation Capital Improvement Percent for Art Funds • Water Department Capital Improvement Percent for Art Funds Artist Selection Process: A “call to artists ” process was issued by the Phoenix Office of Arts and Culture. A 10-member public art panel for the Phoenix Convention Center expansion project was assembled, including local artists and representatives from the Phoenix Arts and Culture Commission, the Phoenix Convention Center, and local cultural organizations. -

Memory and Privacy in the Entire History of You

Memory and Privacy in The Entire History of You Bianca Rodrigues Teixeira and Flavia Maria Santoro 1 Federal University of the State of Rio de Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro, RJ, Brazil {bianca.teixeira, flavia.santoro}@uniriotec.br Abstract. Privacy is a concerning issue today, with millions of people sharing their everyday lives on various social media platforms. Everything people share can be considered as part of their digital memory, which can be consisted of thoughts and feelings posted online. Memory is the focus of “The entire history of you”, third episode of British television series “Black Mirror”. The characters use a device that records and saves what their eyes see, and it's also possible to browse through all previous memories. The device contains most, if not all, of the user's life, which is undoubtedly useful in many daily events, like court cases, debates, reliving previous experiences, security checking, etc. However, it can be a huge problem if somebody tries to see memories that are supposed to be private. To try to combat that possibility, we defined an ontology for Digital Memory and specified our proposal of new features for the device regarding privacy using artificial intelligence. We believe that there is still room for improvement and for more discussion about video-memory and privacy, which is a topic that is not frequently debated. Keywords: memory, privacy, black mirror, ontology 1 Introduction In the past few years, technology has experienced some major advancements. British television series “Black Mirror” highlights several scenarios in which those said advancements could potentially lead to a dystopian society. -

Debut of the Brand's Fairytale First Collection 'Mirror Mirror' in London

J EWELLER Y DIAR Y / J EWELLER Y C OLLEC T IONS Aisha Baker: Debut of the brand’s fairytale first collection ‘Mirror Mirror’ in London May 9, 2018 A pair of earrings, one bracelet and six cocktail rings: these are the novelties that form the debut collection ‘Mirror Mirror,’ created by the new Dubai-based jewellery brand Aisha Baker. isha Baker and Hoonik Chang began working together in 2016 - she is a collector and expert in high jewellery art, he is a qualified jewellery designer and graduate of the prestigious Central Saint A Martins art school. Aisha Baker 'Majesty' earrings in citrine, diamonds, enamel and yellow gold “ “Although we both spend a lot of time in London, Aisha and I are from different countries: I am from South Korea and she is from Dubai,” explains Hoonik during a presentation of the collection at a gallery on Maddox Street. Aisha adds: “I knew Hoonik’s sister for 8 years before I finally met him, and he had just graduated from Saint Martins. We instantly connected!" ” The young graduate’s imagination has sparked some incredible design ideas that he shared with Aisha which she - in turn, thanks to her exquisite taste and understanding of jewellery - has used to achieve the perfect balance between flights of fancy and practicality. Working closely together, the young pair strive to create works of art, personal treasures that can be worn as a reminder of the fact that life is full of magic. Their first jewellery collection, ‘Mirror Mirror’, is a modern interpretation of fairy tales and the world of fantasy. -

Fast Steering Mirror Technology Active Beam Stabilization

APPLICATION NOTE OPTO-MECHANICS 22 Fast Steering Mirror Technology: Active Beam Stabilization Fast Steering Mirror Technology: Active Beam Stabilization By Phillip V. Mitchell, Manager, Technology Development, Newport Corporation The laser is now a firmly established tool in a wide range This paper explores dynamic beam stabilization using a of applications, including semiconductor manufacturing, fast steering mirror (FSM), a technology originally devel- QA/QC, industrial marking, materials processing, bio- oped for demanding aerospace pointing and tracking medical systems, reprographics, information display and requirements. After reviewing the underlying concept of telecommunications. In virtually every one of these dis- beam stabilization and comparing different beam steer- parate applications, it is critically important to avoid fluc- ing technologies, the performance of a closed-loop beam tuations and drifts in laser beam alignment, in order to stabilization system based on FSMs is described. Optical achieve optimum system performance. Furthermore, engineers will find that incorporation of active beam sta- there is continual pressure on optical engineers for high- bilization using FSM technology (Fig. 1) offers a unique er resolution, finer features and greater stability in their and highly advantageous combination of performance designs. This is especially true in the rapidly expanding and cost characteristics. and technology-driven semiconductor and optical telecommunication equipment markets. It is routine in Sources of Beam Misalignment these markets to cut critical dimensions and alignment Laser beam alignment can be characterized by essentially tolerances in half every few years. Failure to meet this two parameters—lateral displacement and angular mis- road map can spell disaster for companies whose chip alignment. Defining the beam direction as the z-axis, lat- life cycles are measured in months. -

1 Sonya Wohletz Spring 2013 Through a Glass, Darkly: a Study Of

Sonya Wohletz Spring 2013 Through a Glass, Darkly: A Study of Mirrors in Aztec Art Introduction As Hernán Cortez and his men made their way to the shores of Mexico, they may have dreamed of the vast treasures in the unknown lands to the West and the shimmering caches of gold that would soon fill their coffers, launching them to the greatest heights of Spanish society. Meanwhile, Motecuzoma II paced his palace chambers, contemplating the dark omens that announced the approach of a sinister band of invaders who would bring an end to his empire. We can imagine his worry and confusion as these strange signs visited upon him a growing kind of terror for which he could not find the language to describe. There is no way Motecuzoma could have envisioned the scale of destruction that awaited him and his people nor the profundity of the changes that the unknown invaders would bring; however, with the help of sages and diviners, Motecuzoma was already encountering clues as to the identity and nature of these unknown beings. Franciscan friar Bernardino de Sahagún, who recorded the stories and cultural customs of native informants in his cultural encyclopedia, The Florentine Codex, describes eight such clues or omens. Of these eight, perhaps the most curious is the seventh omen, in which the royal hunters discovered a bird with a mirror on its forehead: A seventh omen: at one time the fisher folk who hunted or snared with nets took captive an ashen hued bird like a crane. Then they went to show it to Moctezuma, [who was] in the Tlillan calmecatl.1 It was past noon, still daytime. -

What Is Architectural History?

What is Architectural History? Review of: Andrew Leach, What is Architectural History? Polity, Cambridge, 2010. 196pp. ISBN 978-0-7456-4457-8. £14.99. Taking at face value Andrew Leach’s approach to the subject: that architectural historians ‘enact’ a ‘translation’ that responds to the ‘problem of organizing the past of architecture into historical units’ (p.75) then a good place to start reading this book would be the second chapter dedicated precisely to the task of ‘Organizing the past’ (pp.41-75). Here the author convincingly identifies as the principal modern (1880s to present) historical approaches to ‘doing’ architectural history: ‘Style and period’, ‘Biography’, ‘Geography and culture’, ‘Type’, ‘Technique’ and ‘Theme and analogy’. Leach also locates the rise of architectural history within the context of the architectural profession of the same period, but this leads to problems. Whereas military historians and historians of medicine belong to a clear category of academic discipline that operates independently from current military and medical practice, the author has real difficulty in accepting that architectural historians can plausibly occupy a like place as academics functioning separately from current architectural practice. One consequence of this is that Leach evaluates architectural history for its ‘use’ value as though it has to justify itself and its existence within architecture schools, thus re-running a debate of the 1990s when historians were progressively removed or reduced in number in such schools. Although the -

Metallurgy of Zinc, High-Tin Bronze and Gold in Indian Antiquity: Methodological Aspects

Indian Journal of History of Science, 51.1 (2016) 22-32 DOI: 10.16943/ijhs/2016/v51i1/48374 Metallurgy of Zinc, High-tin Bronze and Gold in Indian Antiquity: Methodological Aspects Sharada Srinivasan* (Received 18 August 2015; revised 19 December 2015) Abstract There are inherent challenges in attempting to explore the trajectory of knowledge production vis-a-vis the use of metals in antiquity. Metallurgical innovations, falling as they would have largely done in the domain of empirical knowledge and expertise, would not necessarily have left a systematic written record in the sense of knowledge production. This enquiry is perhaps even more convoluted in the Indian context where in the first place, there are not many detailed records that have readily come to light concerning mining and metallurgy and in the second place, not much systematic archaeometallurgical research has been undertaken. Nevertheless, this paper attempts to demonstrate the role of archaeometallurgical studies, coupled with ethnoarchaeological studies on continuing artisanal technologies, in such enquiries.The paper also seeks to explore the interplay between functional and cultural imperatives through which one may explain the preferential emergence of certain technologies with respect to debates on knowledge production. It restricts itself to selected case studies providing insights into the archaeometallurgy of high-tin bronzes especially from Iron Age Tamil Nadu, zinc smelting evidence at Zawar, Rajasthan, gold working with respect the Nilgiris, and the high-tin bronze mirror craft of Aranmula, Kerala. Key words: Archaeometallurgy, Ethnoarchaeology, High-tin bronze, Iron Age, Megaliths 1. INSIGHTS FROM PROTOHISTORY: SKILLS IN factors may have also played a role in the early MINIATURE AND STANDARDISATION experimentation and discovery of metals and The earliest metallurgists of pre-history materials. -

The Looking-Glass World: Mirrors in Pre-Raphaelite Painting 1850-1915

THE LOOKING-GLASS WORLD Mirrors in Pre-Raphaelite Painting, 1850-1915 TWO VOLUMES VOLUME I Claire Elizabeth Yearwood Ph.D. University of York History of Art October 2014 Abstract This dissertation examines the role of mirrors in Pre-Raphaelite painting as a significant motif that ultimately contributes to the on-going discussion surrounding the problematic PRB label. With varying stylistic objectives that often appear contradictory, as well as the disbandment of the original Brotherhood a few short years after it formed, defining ‘Pre-Raphaelite’ as a style remains an intriguing puzzle. In spite of recurring frequently in the works of the Pre-Raphaelites, particularly in those by Dante Gabriel Rossetti and William Holman Hunt, the mirror has not been thoroughly investigated before. Instead, the use of the mirror is typically mentioned briefly within the larger structure of analysis and most often referred to as a quotation of Jan van Eyck’s Arnolfini Portrait (1434) or as a symbol of vanity without giving further thought to the connotations of the mirror as a distinguishing mark of the movement. I argue for an analysis of the mirror both within the context of iconographic exchange between the original leaders and their later associates and followers, and also that of nineteenth- century glass production. The Pre-Raphaelite use of the mirror establishes a complex iconography that effectively remytholgises an industrial object, conflates contradictory elements of past and present, spiritual and physical, and contributes to a specific artistic dialogue between the disparate strands of the movement that anchors the problematic PRB label within a context of iconographic exchange.