Stained Glass Conservation in Mumbai, India

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Value of Books

The Value of Books: The York Minster Library as a social arena for commodity exchange. Master’s thesis, 60 credits, Spring 2018 Author: Luke Kelly Supervisor: Gudrun Andersson Seminar chair: Dag Lindström Date: 12/01/2018 HISTORISKA INSTITUTIONEN It would be the height of ignorance, and a great irony, if within a work focused on the donations of books, that the author fails to acknowledge and thank those who assisted in its production. Having been distant from both Uppsala and close friends whilst writing this thesis, (and missing dearly the chances to talk to others in person), it goes without saying that this work would not be possible if I had not had the support of many generous and wonderful people. Although to attempt to thank all those who assisted would, I am sure, fail to acknowledge everyone, a few names should be highlighted: Firstly, thank you to all of my fellow EMS students – the time spent in conversation over coffees shaped more of this thesis than you would ever realise. Secondly, to Steven Newman and all in the York Minster Library – without your direction and encouragement I would have failed to start, let alone finish, this thesis. Thirdly, to all members of History Node, especially Mikael Alm – the continued enthusiasm felt from you all reaches further than you know. Fourthly, to my family and closest – thank you for supporting (and proof reading, Maja Drakenberg) me throughout this process. Any success of the work can be attributed to your assistance. Finally, to Gudrun Andersson – thank you for offering guidance and support throughout this thesis’ production. -

Annual Report 2018–2019 Artmuseum.Princeton.Edu

Image Credits Kristina Giasi 3, 13–15, 20, 23–26, 28, 31–38, 40, 45, 48–50, 77–81, 83–86, 88, 90–95, 97, 99 Emile Askey Cover, 1, 2, 5–8, 39, 41, 42, 44, 60, 62, 63, 65–67, 72 Lauren Larsen 11, 16, 22 Alan Huo 17 Ans Narwaz 18, 19, 89 Intersection 21 Greg Heins 29 Jeffrey Evans4, 10, 43, 47, 51 (detail), 53–57, 59, 61, 69, 73, 75 Ralph Koch 52 Christopher Gardner 58 James Prinz Photography 76 Cara Bramson 82, 87 Laura Pedrick 96, 98 Bruce M. White 74 Martin Senn 71 2 Keith Haring, American, 1958–1990. Dog, 1983. Enamel paint on incised wood. The Schorr Family Collection / © The Keith Haring Foundation 4 Frank Stella, American, born 1936. Had Gadya: Front Cover, 1984. Hand-coloring and hand-cut collage with lithograph, linocut, and screenprint. Collection of Preston H. Haskell, Class of 1960 / © 2017 Frank Stella / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York 12 Paul Wyse, Canadian, born United States, born 1970, after a photograph by Timothy Greenfield-Sanders, American, born 1952. Toni Morrison (aka Chloe Anthony Wofford), 2017. Oil on canvas. Princeton University / © Paul Wyse 43 Sally Mann, American, born 1951. Under Blueberry Hill, 1991. Gelatin silver print. Museum purchase, Philip F. Maritz, Class of 1983, Photography Acquisitions Fund 2016-46 / © Sally Mann, Courtesy of Gagosian Gallery © Helen Frankenthaler Foundation 9, 46, 68, 70 © Taiye Idahor 47 © Titus Kaphar 58 © The Estate of Diane Arbus LLC 59 © Jeff Whetstone 61 © Vesna Pavlovic´ 62 © David Hockney 64 © The Henry Moore Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York 65 © Mary Lee Bendolph / Artist Rights Society (ARS), New York 67 © Susan Point 69 © 1973 Charles White Archive 71 © Zilia Sánchez 73 The paper is Opus 100 lb. -

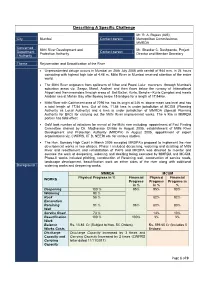

Describing a Specific Challenge

Describing A Specific Challenge Mr. R. A. Rajeev (IAS), City Mumbai Contact person Metropolitan Commissioner, MMRDA Concerned Mithi River Development and Mr. Shankar C. Deshpande, Project Department Contact person Protection Authority Director and Member Secretary / Authority Theme Rejuvenation and Beautification of the River • Unprecedented deluge occurs in Mumbai on 26th July 2005 with rainfall of 944 mm. in 24 hours coinciding with highest high tide of 4.48 m. Mithi River in Mumbai received attention of the entire world. • The Mithi River originates from spillovers of Vihar and Powai Lake traverses through Mumbai's suburban areas viz. Seepz, Marol, Andheri and then flows below the runway of International Airport and then meanders through areas of Bail Bazar, Kurla, Bandra - Kurla Complex and meets Arabian sea at Mahim Bay after flowing below 15 bridges for a length of 17.84Km. • Mithi River with Catchment area of 7295 ha. has its origin at 246 m. above mean sea level and has a total length of 17.84 kms. Out of this, 11.84 kms is under jurisdiction of MCGM (Planning Authority as Local Authority) and 6 kms is under jurisdiction of MMRDA (Special Planning Authority for BKC) for carrying out the Mithi River improvement works. The 6 Km in MMRDA portion has tidal effect. • GoM took number of initiatives for revival of the Mithi river including appointment of Fact Finding Committee chaired by Dr. Madhavrao Chitale in August 2005, establishment of Mithi River Development and Protection Authority (MRDPA) in August 2005, appointment of expert organisations viz. CWPRS, IIT B, NEERI etc. for various studies. -

Literary Miscellany

Literary Miscellany Including Recent Acquisitions. Catalogue 286 WILLIAM REESE COMPANY 409 TEMPLE STREET NEW HAVEN, CT. 06511 USA 203.789.8081 FAX: 203.865.7653 [email protected] www.reeseco.com TERMS Material herein is offered subject to prior sale. All items are as described, but are consid- ered to be sent subject to approval unless otherwise noted. Notice of return must be given within ten days unless specific arrangements are made prior to shipment. All returns must be made conscientiously and expediently. Connecticut residents must be billed state sales tax. Postage and insurance are billed to all non-prepaid domestic orders. Orders shipped outside of the United States are sent by air or courier, unless otherwise requested, with full charges billed at our discretion. The usual courtesy discount is extended only to recognized booksellers who offer reciprocal opportunities from their catalogues or stock. We have 24 hour telephone answering and a Fax machine for receipt of orders or messages. Catalogue orders should be e-mailed to: [email protected] We do not maintain an open bookshop, and a considerable portion of our literature inven- tory is situated in our adjunct office and warehouse in Hamden, CT. Hence, a minimum of 24 hours notice is necessary prior to some items in this catalogue being made available for shipping or inspection (by appointment) in our main offices on Temple Street. We accept payment via Mastercard or Visa, and require the account number, expiration date, CVC code, full billing name, address and telephone number in order to process payment. Institutional billing requirements may, as always, be accommodated upon request. -

York Minster Timeline There Has Been a Minster in York Since AD 627

York Minster Timeline There has been a Minster in York since AD 627. Earlier Minster buildings may have looked like this. The exact location of York Minster the Saxon Minster is not known. From AD 71 From AD 627 Treasure Hunt Discover Where the Minster stands today was The first Minster in York, was small and the treasure once the site of the Roman HQ building. It was in wooden. It was built for the baptism of Edwin, map inside! the middle of a Roman fort. the Saxon King of Northumbria. By AD 640 AD 1080 to AD 1100 A stone Minster had replaced the wooden building. Archbishop Thomas of Bayeux built a This was probably enlarged and improved several Norman Cathedral on the present site. This Minster times before the coming of the Normans. was altered in the 1160s by Archbishop Roger of Pont l’Evéque. AD 1220 Archbishop Walter Gray started to rebuild the South Transept in the Gothic style. (Look at the front page to see it.) Over the next 250 years, the whole of the Minster was slowly rebuilt. The Cathedral you see today was finished in 1472. Welcome to our magnificent Cathedral. This Follow the instructions on your map inside. You Minster or cathedral? What’s the difference? place of Christian worship has been here for will need a pencil to mark the position of each A cathedral church is the mother church of the diocese. It’s where the centuries. It is full of beautiful things waiting treasure. bishop has his seat or ‘cathedra’. -

Books Available to Buy

The Stained Glass Centre: Books Available to Buy If you are interested in purchasing any of the books listed below, please get in contact with the Friends Administrator by post or email: The Stained Glass Centre Friends Administrator, c/o York Glaziers Trust, 6 Deangate, York YO1 7JB, or [email protected] Books can be picked up from the centre by arrangement, made available to collect at any of our upcoming events, or will be posted to you. Postage and packaging prices will be dependent on the weight and size of purchase. Many thanks The Stained Glass Centre Author Title Price Stock History of York Minster (no cover so title and author £1.00 1 unknown) Albutt, R. Stained Glass Windows of AJ Davies of the £25.00 1 Bromsgrove Guild, Worcestershire Albutt, R. Stained Glass Windows of Bromsgrove and Redditch, £8.00 1 Worcestershire Angus, M. Modern Stained Glass in British Churches £5.00 3 Archer, M. Introduction to English Stained Glass £2.00 7 Archer, M. Stained Glass £1.00 4 Armitage, L. Stained Glass £10.00 1 Atterbury, P. Pugin £25.00 2 Aubert, M. Stained Glass of the Xiith and Xiiith Centuries from £12.00 1 French Cathedrals Aubert, M. Le Vitrail en France £5.00 1 Baker, E. Church Archaeology £5.00 1 Baker, J. English Stained Glass of the Medieval Period (83 £10.00 3 Plates) Beaulah, K. Church Tiles of the Nineteenth Century £1.00 1 Beckett, L. & A. York Minster £3.00 1 Hornak Beckett, W. & G. Pains of Glass: The Story of the Passion from King's £2.00 2 Pattison College Chapel, Cambridgeshire Bell, C.C. -

'Daylight Upon Magic': Stained Glass and the Victorian Monarchy

‘Daylight upon magic’: Stained Glass and the Victorian Monarchy Michael Ledger-Lomas If it help, through the senses, to bring home to the heart one more true idea of the glory and the tenderness of God, to stir up one deeper feeling of love, and thankfulness for an example so noble, to mould one life to more earnest walking after such a pattern of self-devotion, or to cast one gleam of brightness and hope over sorrow, by its witness to a continuous life in Christ, in and beyond the grave, their end will have been attained.1 Thus Canon Charles Leslie Courtenay (1816–1894) ended his account of the memorial window to the Prince Consort which the chapter of St George’s Chapel, Windsor had commissioned from George Gilbert Scott and Clayton and Bell. Erected in time for the wedding of Albert’s son the Prince of Wales in 1863, the window attempted to ‘combine the two ele- ments, the purely memorial and the purely religious […] giving to the strictly memorial part, a religious, whilst fully preserving in the strictly religious part, a memorial character’. For Courtenay, a former chaplain- in-ordinary to Queen Victoria, the window asserted the significance of the ‘domestic chapel of the Sovereign’s residence’ in the cult of the Prince Consort, even if Albert’s body had only briefly rested there before being moved to the private mausoleum Victoria was building at Frogmore. This window not only staked a claim but preached a sermon. It proclaimed the ‘Incarnation of the Son of God’, which is the ‘source of all human holiness, the security of the continuousness of life and love in Him, the assurance of the Communion of Saints’. -

The Royal Scottish Academy of Painting', Sculpture Nd

-z CONTENTS Vo1ue One Contents page 2 Acknowledgements Abstract Abbreviations 7 Introduction 9 Chapter One: Beginnings: Education and Taste 14 Chapter Two: 'A little Artistic Society' 37 Chapter Three: 'External Nature or Imaginary Spirits' IL' Chapter Four: Spirits of the enaissance 124 Chapter Five: 'Books Beautiful or Sublime' 154 Chapter Six: 'Little Lyrics' 199 Chapter Seven: Commissions 237 Conclusion 275 Footnotes 260 Bibliography 313 Appendix: Summary Catalogue of Work by Phoebe Traquair Section A: Mural Decorations 322 Section : Painted Furniture; House, Garden and Church Decorations 323 Section C: Paintings, Drawings and Sculpture Section D: Designs for Mural and Furniture Decorations, Embroideries, Illuminated Manuscripts and Enamelwork 337 Section B: EmbroiderIes 3415 Section F: Enamels and Metalwork Section G: Manuscript Illuminations S-fl Section E: Published Designs for Book Covers and Illustrations L'L. Section J: Bookbindings 333 Volumes Two and Three Plates 3 ACKOWLEDGEXE!TS This thesis could not have been researched or written without the willing help of many people. My supervisors, Professor Glies Robertson, who first suggested that I turn my interest in Phoebe Traquair into a university dissertation, and Dr Duncan Macmillan have both been supportive and encouraging at all stages. Members of the Traquair and Moss families have provided warm hospitality and given generously of their time to provide access to their collections and to answer questions which must have seemed endless: in particular I am deeply indebted to the grandchildren of Phoebe Traquair, Ramsay Traquair, Mrs Margaret Anderson, and Mrs Margaret Bartholomew. Francis S Nobbs and his sister, Mrs Phoebe Hyde, Phcebe Traquair's godddaughter, have furnished me with copies of letters written to their father and helped on numerous matters, Without exception owners and. -

The Vulnerability of Global Cities to Climate Hazards

The Vulnerability of Global Cities to Climate Hazards Andrew Schiller*, Alex de SherbininU, Wen-Hua Hsieh*, Alex PulsipherUU * George Perkins Marsh Institute, Clark University U Center for International Earth Science Information Network (CIESIN), Columbia University UU Graduate School of Geography, Clark University Abstract Vulnerability is the degree to which a system or unit is likely to expierence harm due to exposure to perturbations or stress. The vulnerability concept emerged from the recognition that a focus on perturbations alone was insufficient for understanding responses of and impacts on the peoples, ecosystems, and places exposed to such perturbations. With vulnerability, it became clear that the ability of a system to attenuate stresses or cope with consequences constituted an important determinant of system response, and ultimately, of system impact. While vulnerability can expand our ability to understand how harm to people and ecosystems emerges and how it can be reduced, to date vulnerability itself has been conceptually hampered. It tends to address single stresses or perturbations on a system, pays inadequate attention to the full range of conditions that may render the system sensitive to perturbations or permit it to cope, accords short shrift to how exposed systems themselves may act to amplify, attenuate, or even create stresses, and does not emphasize the importance of human-environment interactions when defining the system exposed to stresses. An extended framework for vulnerability designed to meet these needs is emerging from a joint research team at Clark University, the Stockholm Environment Institute, Harvard University, and Stanford University, of which several authors on this paper are part. -

The Gothic Revival Character of Ecclesiastical Stained Glass in Britain

Folia Historiae Artium Seria Nowa, t. 17: 2019 / PL ISSN 0071-6723 MARTIN CRAMPIN University of Wales THE GOTHIC REVIVAL CHARACTER OF ECCLESIASTICAL STAINED GLASS IN BRITAIN At the outset of the nineteenth century, commissions for (1637), which has caused some confusion over the subject new pictorial windows for cathedrals, churches and sec- of the window [Fig. 1].3 ular settings in Britain were few and were usually char- The scene at Shrewsbury is painted on rectangular acterised by the practice of painting on glass in enamels. sheets of glass, although the large window is arched and Skilful use of the technique made it possible to achieve an its framework is subdivided into lancets. The shape of the effect that was similar to oil painting, and had dispensed window demonstrates the influence of the Gothic Revival with the need for leading coloured glass together in the for the design of the new Church of St Alkmund, which medieval manner. In the eighteenth century, exponents was a Georgian building of 1793–1795 built to replace the of the technique included William Price, William Peckitt, medieval church that had been pulled down. The Gothic Thomas Jervais and Francis Eginton, and although the ex- Revival was well underway in Britain by the second half quisite painterly qualities of the best of their windows are of the eighteenth century, particularly among aristocratic sometimes exceptional, their reputation was tarnished for patrons who built and re-fashioned their country homes many years following the rejection of the style in Britain with Gothic features, complete with furniture and stained during the mid-nineteenth century.1 glass inspired by the Middle Ages. -

9. Environmental and Social Impact Assessment

TECHNO-ECONOMIC SURVEY AND PREPARATION OF DPR FOR PANVEL-DIVA-VASAI-VIRAR CORRIDOR 9. ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT 9.1 ENVIRONMENTAL BASELINE DATA The main aim of the Environmental and Social Impact Assessment (ESIA) study is to ascertain the existing baseline conditions and to assess the impacts of all the factors as a result of the proposed New Sub-urban corridor on Virar-Vasai Road-Diva-Panvel section. The changes likely to occur in different components of the environment viz. Natural Physical Resources, Natural Ecological (or Biological) Resources, Human/Economic Development Resources (Human use values), Quality of life values (socio-economic), would be studied and assessed to a reasonable accuracy. The environment includes Water Quality, Air Quality, Soils, Noise, Ecology, Socio-economic issues, Archaeological /historical monuments etc. The information presented in this section stems from various sources such as reports, field surveys and monitoring. Majority of data on soil, water quality, air and noise quality, flora and fauna were collected during field studies. This data have been further utilized to assess the incremental impact, if any, due to the project. The development/compilation of environmental baseline data is essential to assess the impact on environment due to the project. The proposed new suburban corridor from Panvel to Virar is to run along the existing Panvel-Diva-Vasai line of Central Railway and then Vasai Road to Virar to Western Railway.The corridor is 69.50 km having 24 stations on Panvel-Virar section. Land Environment The project area is situated in Mumbai, the commercial capital of India. The average elevation of Mumbai plains is 14 m above the mean sea level. -

The Birmingham & Midland Institute

THE BIRMINGHAM & MIDLAND INSTITUTE What's On July - December 2019 SCIENCE ARTS LITERATURE 1 About the BMI The Birmingham & Midland Institute has been at the heart of Birmingham’s cultural life for over 150 years. It was originally founded by Act of Parliament in 1854 for the ‘Diffusion and Advancement of Science, Literature and Art amongst all Classes of Persons resident in Birmingham and Midland Counties’. Charles Dickens was one of its early Presidents. CONTENTS During the late nineteenth century, the BMI played a leading role in the introduction of scientific and technical education in Season Highlights 2 Birmingham until the state gradually took over its functions. It was thus the forerunner of many educational bodies such Art 4 as the Birmingham Conservatoire. Located in a Grade II* listed building, the BMI Room and Venue Hire 6 has a thriving programme of cultural and educational activities, which includes a wide Music 7 spectrum of arts and science lectures, exhibitions and concerts. The building is also a venue for many externally-organised events Literature 8 and can be booked for conferences and meetings. The Birmingham Library 7 The BMI has longstanding associations with a number of independent societies who use Affiliated Societies 18 the premises for their activities and meetings. Affiliated societies have kindred interests and and Joint Events include the Birmingham Philatelic Society and the Birmingham and Midland Society for Genealogy and Heraldry. The BMI receives no public subsidy or direct revenue funding; it depends entirely on income generated through the support of members, visitors, donors, and volunteers. Visit our website, Facebook and Twitter pages for the latest updates on events and activities! SEASON HIGHLIGHTS DRAWING ON RUSKIN FREE ENTRY DROP-IN, NO NEED TO BOOK Keep an eye out for an exciting, long term drawing project starting in the spring and leading to an exhibition in the autumn.