Mapping Richmond's World War Ii Home Front

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CPY Document Title

Agenda Item 7b Attachment A Proposition 23 Supporters (As of August 17, 2010 ) State and National Organizations State and National Organizations (cont’d) American Council of Engineering Companies – Lumber Association of California and California Nevada American GI Forum of California National Federation of Independent Business American GI Forum Women of California – California (NFIB) Americans for Prosperity National Petrochemical and Refiners Associated California Loggers Association Association of Energy Service Companies National Tax Limitation Committee Black Business Association National Taxpayers Union California Association of Business and Nisei Farmers League Property Owners Printing Industries of California California Automotive Wholesalers Slavic American Chamber of Commerce Association Waste Watchers California Cattlemen’s Association Western Agricultural Processors Association California Citrus Mutual California Coalition of Filipino American Chambers Air Quality/Public Health Officials California Cotton Ginners and Growers Peter Foy, Ventura County Air Pollution Associations Control District Board Member California Dairy Campaign Brad Mitzelfelt, Mojave Desert Air Quality California Dump Truck Owners Association Management District Board Member California Hispanic Chambers of Commerce Reb Monaco, Monterey Bay Unified Air California Independent Oil Marketers Pollution Control District Board Member Association (CIOMA) Kim Yamaguchi, Butte County Air Quality California League of Food Processors Management District Board Member -

Effectiveness of Larger-Area Exclusion Booming to Protect Sensitive Sites in San Francisco Bay

Effectiveness of Larger-Area Exclusion Booming to Protect Sensitive Sites in San Francisco Bay Final Report Prepared for California Department of Fish & Game Oil Spill Prevention and Response (OSPR) 425 G Executive Court North Fairfield, CA 94534-4019 Prepared by Dagmar Schmidt Etkin, PhD Environmental Research Consulting 41 Croft Lane Cortlandt Manor, NY 10567-1160 SSEP Contract No. P0775013 30 September 2009 Effectiveness of Larger-Area Exclusion Booming to Protect Sensitive Sites in San Francisco Bay Final Report Prepared by Dagmar Schmidt Etkin, PhD Environmental Research Consulting 41 Croft Lane Cortlandt Manor, NY 10567-1160 USA Prepared at the Request of Carl Jochums California Department of Fish & Game Oil Spill Prevention and Response (OSPR) 425 G Executive Court North Fairfield, CA 94534-4019 Submitted to Bruce Joab, SSEP Coordinator and Contract Manager Office of Spill Prevention and Response CA Department of Fish and Game 1700 K Street, Suite 250 Sacramento, CA 95811 Phone 916-322-7561 SSEP Contract No. PO775013 Note: This study was conducted in collaboration with Applied Science Associates (ASA), Inc., of South Kingston, RI, under SSEP Contract No. PO775010. ASA submitted a separate Final Report entitled Transport and Impacts of Oil Spills in San Francisco Bay – Implications for Response. i Effectiveness of Larger-Area Exclusion Booming to Protect Sensitive Sites in San Francisco Bay Contents Contents ....................................................................................................................................................... -

The Year's Music

This is a reproduction of a library book that was digitized by Google as part of an ongoing effort to preserve the information in books and make it universally accessible. https://books.google.com fti E Y LAKS MV5IC 1896 juu> S-q. SV- THE YEAR'S MUSIC. PIANOS FOR HIRE Cramer FOR HARVARD COLLEGE LIBRARY Pianos BY All THE BEQUEST OF EVERT JANSEN WENDELL (CLASS OF 1882) OF NEW YORK Makers. 1918 THIS^BQQKJS FOR USE 1 WITHIN THE LIBRARY ONLY 207 & 209, REGENT STREET, REST, E.C. A D VERTISEMENTS. A NOVEL PROGRAMME for a BALLAD CONCERT, OR A Complete Oratorio, Opera Recital, Opera and Operetta in Costume, and Ballad Concert Party. MADAME FANNY MOODY AND MR. CHARLES MANNERS, Prima Donna Soprano and Principal Bass of Royal Italian Opera, Covent Garden, London ; also of 5UI the principal ©ratorio, dJrtlustra, artii Sgmphoiu) Cxmctria of ©wat Jfvitain, Jtmmca anb Canaba, With their Full Party, comprising altogether Five Vocalists and Three Instrumentalists, Are now Booking Engagements for the Coming Season. Suggested Programme for Ballad and Opera (in Costume) Concert. Part I. could consist of Ballads, Scenas, Duets, Violin Solos, &c. Lasting for about an hour and a quarter. Part II. Opera or Operetta in Costume. To play an hour or an hour and a half. Suggested Programme for a Choral Society. Part I. A Small Oratorio work with Chorus. Part II. An Operetta in Costume; or the whole party can be engaged for a whole work (Oratorio or Opera), or Opera in Costume, or Recital. REPERTOIRE. Faust (Gounod), Philemon and Baucis {Gounod) (by arrangement with Sir Augustus Harris), Maritana (Wallace), Bohemian Girl (Balfe), and most of the usual Oratorios, &c. -

City of San Pablo Affordable Housing Strategy

CITY OF SAN PABLO AFFORDABLE HOUSING STRATEGY Prepared for: City of San Pablo November 9, 2020 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................................... 5 Effects of COVID-19 on Housing Affordability ..................................................................................... 5 Process for Developing the AHS .......................................................................................................... 6 EXISTING CONDITIONS ....................................................................................................................... 8 Housing Supply ..................................................................................................................................... 8 Existing Housing Affordability Needs ............................................................................................... 15 Existing Resources, Policies, and Programs .................................................................................... 21 RESIDENTIAL MARKET CONDITIONS IN SAN PABLO ...................................................................... 27 Residential Market Supply and Trends ............................................................................................ 27 Opportunities and Constraints for Development ............................................................................ 34 OVERVIEW OF THE IMPLEMENTATION PLAN ................................................................................. -

Veterans Day Aboard the SS Red Oak Victory

Veterans Day Aboard the SS Red Oak Victory Hundreds packed the partly restored World War II cargo ship in Richmond Friday to honor and celebrate veterans. By Soren Hemmila Veterans Day aboard the SS Red Oak Victory ship Supervisor John Gioia, with Mariam Sauer, an original Rosie the Riveter, help re-christen SS Red Oak Victory ship in Richmond, Veterans Day, Nov. 11, 2011. A large-than-expected crowd attended a Veterans Day event aboard the SS Red Oak Victory in Richmond Friday. The Chevron-sponsored gathering honored those who served abroad in America’s armed services as well as those who supported the war effort at home. With the threat of rain, the ceremony was moved inside the Red Oak. Hundreds packed into the hull of the cargo vessel to listen to stories of Richmond during the war years. An original "Rosie the Riveter" was on hand to help re-christen the Kaiser-built vessel. Richmond native Mariam Sauer, along with Contra Costa County Supervisor John Gioia and Richmond Vice Mayor Tom Butt, smashed a champagne bottle to reenact the 1944 launch of the munitions carrier. The ship recently underwent extensive repairs in dry dock and received a fresh coat of paint. According to the Richmond Museum of History, the Red Oak is the Victory ship from the Richmond shipyard that is being restored. Russ Yarrow of Chevron detailed the role the Richmond refinery played during World War II. The refinery won numerous production and development awards during the war. It developed special submarine lubricants and produced 100 octane aviation fuel necessary for America’s war effort. -

Richmond Area Community-Based Transportation Plan Contra Costa Transportation Authority

Steering Committee Draft | Ocotber 2020 Richmond Area Community-Based Transportation Plan Contra Costa Transportation Authority Steering Committee Draft | Ocotber 2020 Richmond Area Community-Based Transportation Plan Contra Costa Transportation Authority Prepared By: 1625 Shattuck Avenue Suite 300 Berkeley, California 94709 510.848.3815 ORANGE COUNTY • BAY AREA • SACRAMENTO • CENTRAL COAST • LOS ANGELES • INLAND EMPIRE • SAN DIEGO www.placeworks.com Table of Contents List of Figures & Tables ii Executive Summary 3 1. Introduction 13 1.1 Metropolitan Transportation Commission Lifeline Transportation Program 13 1.2 CBTP Guidelines 14 1.3 2004 Richmond-Area CBTP 15 1.4 Current Richmond Area CBTP 15 1.5 COVID-19 and CBTP Development 17 2. Study Area Profile 18 2.1 Demographic Analysis 18 2.2 Transportation Patterns 24 2.3 Transportation Network 28 3. Previous Studies and Mobility Gaps 33 3.1 Local Studies 33 3.2 Countywide Studies 37 3.3 Current Studies 39 3.4 Thematic Mobility Challenges 40 4. Outreach and Engagement Summary 43 4.1 CBTP Advisor Groups 43 4.2 Outreach Strategy 44 4.3 Outreach Awareness 44 4.4 Outreach Results 46 4.5 Outreach Summary 54 5. Methodology and Recommendations 56 5.1 COVID-19 and CBTP Development 56 5.2 Evaluation Criteria 57 5.3 Evaluation Process 60 5.4 Recommended Projects and Plans 62 Appendix A Existing Conditions Report Appendix B Outreach Materials and Results Appendix C Recommendations Scoring Results Richmond Area Community-Based Transportation Plan i Contra Costa Transportation Authority List of Figures -

Anton Wolken Dies in Fairbury Hospital Friday Birds Romp for 53

N O . 13 EIGHTY-FIRST YEAR CHATSWORTH, ILLINOIS, THURSDAY, NOVEMBER 11, 1954 The Younger Generation Chorus Appears for Ortman Electric TO OUR SUBSCRIBERS Birds Romp for Anton Wolken V ets A t D a n v ille Postal regulations now re Store Robbed Approximately thirty members quire payment of subscrip I C. Louis Ortman Electric Shop of the mixed chorus of voices who tions within six month* of was robbed about 3 a.m., Sunday. 53 to 0 Win Dies In Fairbury appeared In the Lions Minstrel when they are due. You can jThe burglary was discovered Sun- Revue here tn September, present help us keep our subscription j day morning when Mr. Ortman ed two performances in the the list up to date by checking j came down to his shop about 10 a. atre of the Vets hospital in Dan when your subscription ex m. A safe was broken into and a Over Kempton Hospital Friday ville Sunday afternoon. pires and paying it prompt considerable amount of money and Under the direction of Joseph ly. The date your paper ex old coins were stolen. Battle Eskimos H. Bauer, with Faye Shafer or pires is printed right beside The time of the robbery was Was Long Time ganist and Mrs. Howard Trinkle your name at the top of the set at three o’clock when the elec Armistice Evening Resident of pianist, with several soloists in the front page. Thank you. tric clocks were stopped In the es In Final Game left to right in this picture are: Peggy, ltt years old, cast, the chorus performed at 2:15 tablishment and the business place and Jerry Lm * 2 months, children of Mr. -

Board Meeting Packet

Board of Directors Board Meeting Packet December 5, 2017 Clerk of the Board YOLANDE BARIAL KNIGHT (510) 544-2020 PH MEMO to the BOARD OF DIRECTORS (510) 569-1417 FAX EAST BAY REGIONAL PARK DISTRICT East Bay Regional Park District Board of Directors BEVERLY LANE The Regular Session of the December 5, 2017 President - Ward 6 Board Meeting is scheduled to commence at 1:00 p.m. at the EBRPD Administration Building, DENNIS WAESPI 2950 Peralta Oaks Court, Oakland Vice President - Ward 3 AYN WIESKAMP Treasurer - Ward 5 ELLEN CORBETT Secretary - Ward 4 Respectfully submitted, WHITNEY DOTSON Ward 1 DEE ROSARIO Ward 2 COLIN COFFEY ROBERT E. DOYLE Ward 7 General Manager ROBERT E. DOYLE General Manager P.O. Box 5381 2950 Peralta Oaks Court Oakland, CA 94605-0381 (888) 327-2757 MAIN (510) 633-0460 TDD (510) 635-5502 FAX www.ebparks.org AGENDA REGULAR MEETING OF DECEMBER 5, 2017 BOARD OF DIRECTORS EAST BAY REGIONAL PARK DISTRICT The Board of Directors of 11:30 a.m. ROLL CALL (Board Conference Room) the East Bay Regional Park District will hold a regular meeting at District’s PUBLIC COMMENTS Administration Building, 2950 Peralta Oaks Court, Oakland, CLOSED SESSION CA, commencing at 11:30 a.m. for Closed Session and 1:00 p.m. A. Conference with Labor Negotiator: Government Code Section 54957.6 for Open Session on Tuesday, December 5, 2017. 1. Agency Negotiator: Robert E. Doyle, Ana M. Alvarez Agenda for the meeting is Employee Organizations: AFSCME Local 2428, listed adjacent. Times for agenda Police Association items are approximate only and Unrepresented Employees: Managers and Confidentials are subject to change during the meeting. -

West Contra Costa/Albany Transit Wayfinding Plan

FINAL WEST CONTRA COSTA TRANSIT ENHANCEMENT STRATEGIC PLAN and WEST CONTRA COSTA/ALBANY TRANSIT WAYFINDING PLAN Prepared for: West Contra Costa Transportation Advisory Committee October 2011 Acknowledgements WCCTAC BOARD City of El Cerrito Janet Abelson, Vice Chair City of Hercules Donald Kuehne City of Pinole Roy Swearingen, Chair City of Richmond Courtland “Corky” Boozé City of Richmond Thomas Butt City of Richmond Jeff Ritterman City of San Pablo Genoveva Calloway AC Transit Joe Wallace BART Joel Keller WestCAT Tom Hansen Contra Costa County John Gioia WCCTAC STAFF Christina Atienza, Executive Director Linda Young John Rudolph Joanna Pollock WCCTAC WORKING GROUP City of El Cerrito Yvetteh Ortiz City of Hercules Robert Reber City of Pinole Winston Rhodes City of Richmond Chad Smalley, Hector Rojas, Steven Tam City of San Pablo Kanwal Sandhu, Adele Ho AC Transit Nathan Landau, Puja Sarna, Aaron Priven BART Diedre Heitman WestCAT Rob Thompson Contra Costa County Jamar Stamps MTC Jay Stagi CONSULTANT TEAM Fehr & Peers Nelson/Nygaard Bob Grandy (Project Manager) Linda Rhine Brooke DuBose (Deputy PM) Joey Goldman Matthew Ridgway Meghan Mitman Studio L’Image Ellen Poling Sue Labouvie Josh Peterman Max Heim Steve Rhyne Carrie Carsell Eisen Letunic Nikki Hervol Niko Letunic Nikki Foletta table of contents I Introduction II Study Locations III Community Participation IV Travel Demand Management & Parking Strategies V Richmond BART Transit Center Enhancement Strategies VI Richmond Parkway Transit Center Enhancement Strategies VII El Cerrito Del -

AMERICAN MANHOOD in the CIVIL WAR ERA a Dissertation Submitted

UNMADE: AMERICAN MANHOOD IN THE CIVIL WAR ERA A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Notre Dame in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor in Philosophy by Michael E. DeGruccio _________________________________ Gail Bederman, Director Graduate Program in History Notre Dame, Indiana July 2007 UNMADE: AMERICAN MANHOOD IN THE CIVIL WAR ERA Abstract by Michael E. DeGruccio This dissertation is ultimately a story about men trying to tell stories about themselves. The central character driving the narrative is a relatively obscure officer, George W. Cole, who gained modest fame in central New York for leading a regiment of black soldiers under the controversial General Benjamin Butler, and, later, for killing his attorney after returning home from the war. By weaving Cole into overlapping micro-narratives about violence between white officers and black troops, hidden war injuries, the personal struggles of fellow officers, the unbounded ambition of his highest commander, Benjamin Butler, and the melancholy life of his wife Mary Barto Cole, this dissertation fleshes out the essence of the emergent myth of self-made manhood and its relationship to the war era. It also provides connective tissue between the top-down war histories of generals and epic battles and the many social histories about the “common soldier” that have been written consciously to push the historiography away from military brass and Lincoln’s administration. Throughout this dissertation, mediating figures like Cole and those who surrounded him—all of lesser ranks like major, colonel, sergeant, or captain—hem together what has previously seemed like the disconnected experiences of the Union military leaders, and lowly privates in the field, especially African American troops. -

Friends of Five Creeks Letters Re Restoration of Codornices Creek

The letters below deal with F5C’s early involvement in Codornices Creek. They shed some light on challenges that faced efforts to restore our area’s only trout stream, and the role citizens played. These are by no means the whole story. Most credit for the big projects on Codornices west of San Pablo goes to the partnership of creek-restoration pioneers Carole Schemmerling, who headed the now defunct Urban Creeks Council, and consulting hydrologist Dr. Ann Riley, whose now defunct private consulting firm Watershed Restoration Institute. The two shared offices; UCC was effectively the nonprofit arm of WRI, able to receive grants and similar government support. Credit also goes to longtime environmental visionary Richard Register, who with UCC played a large role in bringing Codornices out of its pipe between 8th and 9th Streets in 1994-5. This was one of Berkeley’s pioneer “daylighting” projects. Friends of Five Creeks 1000 San Pablo Ave. Albany, CA 94706 412 7257 October 4, 1998 Mr. Ron Gervason San Francisco Bay Regional Water Quality Control Board 1515 Clay St., 14th Floor Oakland, CA 94612 [email protected] Re: Triannual Review of Water Quality Control Plan of San Francisco Bay Basin Friends of Five Creeks is a grassroots organization that seeks to protect and restore creeks in Albany, California. While Albany’s natural creeks are mostly in culverts, one, Codornices, is substantially free flowing and has a small trout population. Efforts are ongoing to restore another, Cerrito Creek. We believe that the few creeks in our urbanized area that can or do support relatively natural aquatic life, especially cold-water or anadromous fish, should receive the highest possible degree of protection, including that of the Regional Water Quality Control Board. -

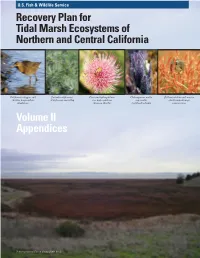

Tidal Marsh Recovery Plan Habitat Creation Or Enhancement Project Within 5 Miles of OAK

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Recovery Plan for Tidal Marsh Ecosystems of Northern and Central California California clapper rail Suaeda californica Cirsium hydrophilum Chloropyron molle Salt marsh harvest mouse (Rallus longirostris (California sea-blite) var. hydrophilum ssp. molle (Reithrodontomys obsoletus) (Suisun thistle) (soft bird’s-beak) raviventris) Volume II Appendices Tidal marsh at China Camp State Park. VII. APPENDICES Appendix A Species referred to in this recovery plan……………....…………………….3 Appendix B Recovery Priority Ranking System for Endangered and Threatened Species..........................................................................................................11 Appendix C Species of Concern or Regional Conservation Significance in Tidal Marsh Ecosystems of Northern and Central California….......................................13 Appendix D Agencies, organizations, and websites involved with tidal marsh Recovery.................................................................................................... 189 Appendix E Environmental contaminants in San Francisco Bay...................................193 Appendix F Population Persistence Modeling for Recovery Plan for Tidal Marsh Ecosystems of Northern and Central California with Intial Application to California clapper rail …............................................................................209 Appendix G Glossary……………......................................................................………229 Appendix H Summary of Major Public Comments and Service