Beasts and Abominations in Things Fall Apart and Omenuko Hugh Hodges

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

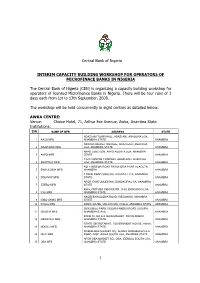

Interim Capacity Building for Operators of Microfinance Banks

Central Bank of Nigeria INTERIM CAPACITY BUILDING WORKSHOP FOR OPERATORS OF MICROFINACE BANKS IN NIGERIA The Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN) is organizing a capacity building workshop for operators of licensed Microfinance Banks in Nigeria. There will be four runs of 3 days each from 1st to 13th September, 2008. The workshop will be held concurrently in eight centres as detailed below: AWKA CENTRE: Venue: Choice Hotel, 71, Arthur Eze Avenue, Awka, Anambra State. Institutions: S/N NAME OF MFB ADDRESS STATE ADAZI ANI TOWN HALL, ADAZI ANI, ANAOCHA LGA, 1 AACB MFB ANAMBRA STATE ANAMBRA NKWOR MARKET SQUARE, ADAZI-ENU, ANAOCHA 2 ADAZI-ENU MFB LGA, ANAMBRA STATE ANAMBRA AKPO JUNCTION, AKPO AGUATA LGA, ANAMBRA 3 AKPO MFB STATE ANAMBRA CIVIC CENTRE COMPLEX, ADAZI-ENU, ANAOCHA 4 BESTWAY MFB LGA, ANAMBRA STATE ANAMBRA NO 1 MISSION ROAD EKWULOBIA P.M.B.24 AGUTA, 5 EKWULOBIA MFB ANAMBRA ANAMBRA 1 BANK ROAD UMUCHU, AGUATA L.G.A, ANAMBRA 6 EQUINOX MFB STATE ANAMBRA AFOR IGWE UMUDIOKA, DUNUKOFIA LGA, ANAMBRA 7 EZEBO MFB STATE ANAMBRA KM 6, ONITHSA OKIGWE RD., ICHI, EKWUSIGO LGA, 8 ICHI MFB ANAMBRA STATE ANAMBRA NNOBI/EKWULOBIA ROAD, IGBOUKWU, ANAMBRA 9 IGBO-UKWU MFB STATE ANAMBRA 10 IHIALA MFB BANK HOUSE, ORLU ROAD, IHIALA, ANAMBRA STATE ANAMBRA EKWUSIGO PARK, ISUOFIA-NNEWI ROAD, ISUOFIA, 11 ISUOFIA MFB ANAMBRA STATE ANAMBRA ZONE 16, NO.6-9, MAIN MARKET, NKWO-NNEWI, 12 MBAWULU MFB ANAMBRA STATE ANAMBRA STATE SECRETARIAT, GOVERNMENT HOUSE, AWKA, 13 NDIOLU MFB ANAMBRA STATE ANAMBRA NGENE-OKA MARKET SQ., ALONG AMAWBIA/AGULU 14 NICE MFB ROAD, NISE, AWKA SOUTH -

Post-Colonial Subjectivity in Achebe's Things Fall Apart Christopher Wise Western Washington University, [email protected]

Western Washington University Western CEDAR English Faculty and Staff ubP lications English Fall 1999 Excavating the New Republic: Post-Colonial Subjectivity in Achebe's Things Fall Apart Christopher Wise Western Washington University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://cedar.wwu.edu/english_facpubs Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Wise, Christopher, "Excavating the New Republic: Post-Colonial Subjectivity in Achebe's Things Fall Apart" (1999). English Faculty and Staff Publications. 3. https://cedar.wwu.edu/english_facpubs/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the English at Western CEDAR. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Faculty and Staff Publications by an authorized administrator of Western CEDAR. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NEW REPUBLIC EXCAVATING THE EXCAVATING THE NEW REPUBLIC Post-colonial Subjectivity in Achebe's Things Fall Apart by Christopher Wise "[I]t may be productive [today] to think in terms of a genuine transformation of being which takes place when the individual subject shifts from purely individual relations to that very differ- ent dynamic which is that of groups, collectives and communi- ties ... The transformation of being ... is something that can be empirically experienced ... by participation in group praxis-an experience no longer as rare as it was before the 1960s, but still rare enough to convey a genuine ontological shock, and the momentary restructuration and placing -

Proverb Usage in African Literature

International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Invention ISSN (Online): 2319 – 7722, ISSN (Print): 2319 – 7714 www.ijhssi.org Volume 4 Issue 3 || March. 2015 || PP. 30-35 Proverb Usage in African Literature 1Adaobi Olivia Ihueze, 2 Prof. Rems Umeasiegbu 1Department of English Language and Literature,Nnamdi Azikiwe University, Awka Nigeria. 2 Department of English Language and Literature, Nnamdi Azikiwe University, Awka Nigeria ABSTRACT: This study analyzes the integration of proverbs in Flora Nwapa’s Efuru and Elechi Amadi’s The Concubine and The Great Ponds that is their active and passive usages. The proverbs were isolated and related to available data in published works to ensure that they are real oral lore. Rems Umeasiegbu’s reflective model for assessment of Igbo proverbs that was used to test Chinua Achebe’s works was used to asses Flora Nwapa and Elechi Amadi’s use”of proverbs. They tallied. The model shows that they have really used proverbs effectively. The work concludes that the model for the study of proverbs used in Achebe’s novels fits very well the proverbs used by Flora Nwapa and Elechi Amadi. KEY WORDS: Active, assessment, folklore, passive, proverb and reflective, I. INTRODUCTION Proverbs are essential to life and language, and without them, the language will be but a skeleton without flesh, a body without a soul. It is also used to add colour to every conversation. In the foreword to W. H. Whitely‟s Selection of African Prose,(1964) the Nigerian novelist Chinua Achebe says this about a proverb … In Igbo they serve two important ends. -

Historical Dynamics of Ọjị Ezinihitte Cultural Festival in Igboland, Nigeria

67 International Journal of Modern Anthropology Int. J. Mod. Anthrop. 2020. Vol. 2, Issue 13, pp: 67 - 98 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.4314/ijma.v2i13.2 Available online at: www.ata.org.tn & https://www.ajol.info/index.php/ijma Research Article Historical dynamics of Ọjị Ezinihitte cultural festival in Igboland, Nigeria Akachi Odoemene Department of History and International Studies, Federal University Otuoke, Bayelsa State, Nigeria E-mail: [email protected] (Received 6 January 2020; Accepted 16 May 2020; Published 6 June 2020) Abstract - Ọjị (kola nut) is indispensable in traditional life of the Igbo of Nigeria. It plays an intrinsic role in almost all segments of the people‟s cultural life. In the Ọjị Ezinihitte festivity the „kola tradition‟ is meaningfully and elaborately celebrated. This article examines the importance of Ọjị within the context of Ezinihitte socio-cultural heritage, and equally accounts for continuity and change within it. An eclectic framework in data collection was utilized for this research. This involved the use of key-informant interviews, direct observation as well as extant textual sources (both published and un-published), including archival documents, for the purposes of the study. In terms of analysis, the study utilized the qualitative analytical approach. This was employed towards ensuring that the three basic purposes of this study – exploration, description and explanation – are well articulated and attained. The paper provided background for a proper understanding of the „sacred origin‟ of the Ọjị festive celebration. Through a vivid account of the festival‟s processes and rituals, it achieved a reconstruction of the festivity‟s origins and evolutionary trajectories and argues the festival as reflecting the people‟s spirit of fraternity and conviviality. -

Nigeria's Constitution of 1999

PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:42 constituteproject.org Nigeria's Constitution of 1999 This complete constitution has been generated from excerpts of texts from the repository of the Comparative Constitutions Project, and distributed on constituteproject.org. constituteproject.org PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:42 Table of contents Preamble . 5 Chapter I: General Provisions . 5 Part I: Federal Republic of Nigeria . 5 Part II: Powers of the Federal Republic of Nigeria . 6 Chapter II: Fundamental Objectives and Directive Principles of State Policy . 13 Chapter III: Citizenship . 17 Chapter IV: Fundamental Rights . 20 Chapter V: The Legislature . 28 Part I: National Assembly . 28 A. Composition and Staff of National Assembly . 28 B. Procedure for Summoning and Dissolution of National Assembly . 29 C. Qualifications for Membership of National Assembly and Right of Attendance . 32 D. Elections to National Assembly . 35 E. Powers and Control over Public Funds . 36 Part II: House of Assembly of a State . 40 A. Composition and Staff of House of Assembly . 40 B. Procedure for Summoning and Dissolution of House of Assembly . 41 C. Qualification for Membership of House of Assembly and Right of Attendance . 43 D. Elections to a House of Assembly . 45 E. Powers and Control over Public Funds . 47 Chapter VI: The Executive . 50 Part I: Federal Executive . 50 A. The President of the Federation . 50 B. Establishment of Certain Federal Executive Bodies . 58 C. Public Revenue . 61 D. The Public Service of the Federation . 63 Part II: State Executive . 65 A. Governor of a State . 65 B. Establishment of Certain State Executive Bodies . -

Chinua Achebe's Things Fall Apart and Nigerian Education

ariel: a review of international english literature Vol. 46 No. 3 Pages 91–112 Copyright © 2015 The Johns Hopkins University Press and the University of Calgary Playful Ethnography: Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart and Nigerian Education David Borman Abstract: This paper looks at the critical and popular reception of Chinua Achebe’s first novel, Things Fall Apart, as an authentic text offering an “insider” perspective on Igbo culture. Drawing from small magazines and university publications in 1950s Nigeria, this paper suggests that early Nigerian authors like Achebe were edu- cated and began writing in a culture that valued a playful explora- tion of meaning in Western texts. These early publications express multiple uses of the texts students read in colonial school, and I read Achebe’s novel as an extension of this playfulness. Although it is generally seen as an example of the empire “writing back,” I argue that Things Fall Apart actually uses ethnographic accounts of Nigerian village life—especially G. T. Basden’s Niger Ibos and C. K. Meek’s Law and Authority in a Nigerian Tribe—in an open and exploratory manner. Seeing Achebe’s work in this light allows for a complex view of the novel’s presentation of Igbo life, and I argue that such a reading resituates his first novel as a playful encounter with ethnography rather than as a literary response to more tradi- tional literary texts like Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness or Joyce Cary’s Mister Johnson. Keywords: Chinua Achebe; Things Fall Apart; writing back; eth- nography; play The June 20, 1958 edition of the Times Literary Supplement contains one short review of Chinua Achebe’s first novel, Things Fall Apart, re- cently published with a print run of two thousand hardcover copies by Heinemann’s educational department. -

Achebe's Novels and the Story of Nigeria

Vol. 2(10), pp. 230-232, October 2014 DOI: 10.14662/IJELC2014.067 International Journal of English Copy©right 2014 Literature and Culture Author(s) retain the copyright of this article ISSN: 2360-7831©2014 Academic Research Journals http://www.academicresearchjournals.org/IJELC/Index.htm Review REVISITING AND RETELLING THE HISTORY: ACHEBE‟S NOVELS AND THE STORY OF NIGERIA Anand .P Guest Lecturer, M.E.S Keveeyam College, Calicut University. Email:[email protected], Ph: 9567147724. Accepted 24 October 2014 It was part of the colonial project to highlight an image of the colonized as a mass without proper cultural roots and history. This was a means to justify Euro-centrism. It is after long years of anti- colonial struggle, political independence „emerged‟. As a result post-colonial novels of the 1950‟s were essentially case studies of these struggles, in other words they were about history. Colonizer‟s version of history was a mere distorted version of reality suppressing the facts related to orient culture and life. But these novels are experiments in history challenging the „so called‟ authentic version. This narration of native history utilizes the resources in native forms of history-recording such as the folk songs, folk tales, stories etc. Chinua Achebe‟s novels Things Fall Apart and Arrow of God set in early colonial days is actually a work in historical revisionism concentrating the spread of Christianity, the decline of native religions, and also the colonial measures of tactful and “effective” governance. Keywords: History, Revisionist Reading, African Trilogy, Nigeria, Chinua Achebe, Post Colonialism Cite This Article As: Anand P (2014). -

Abomination Voices Cry out As Figures Leap from the Treeline to Ambush a Traveling Elf in the Fading Twilight

Abomination Voices cry out as figures leap from the treeline to ambush a traveling elf in the fading twilight. Only seconds pass before The Abomination their cries of battle turn to cries of fear as the elf howls and becomes a whirlwind of teeth and claws, embracing the beast Proficiency within. Level Bonus Features Mutations A halfling lurks beneath the tranquil surface of the river, 1st +2 Abominable Form, — waiting for the bandit encampment to draw near. As soon as Abominable Influence one of them gets within reach, she explodes out of the water 2nd +2 Mutations 2 as a slimy mass of tentacles and aberrant eyes. A hulking creature with crimson skin makes quick work of 3rd +2 Frightful Gaze, 2 the orcs, slamming them to the side with every combination Uncanny Speed of claws, teeth, and curling black horns. When the bloodshed 4th +2 Ability Score Improvement 3 is done, the creature approaches the captives at the center of 5th +3 Extra Attack 3 the camp. A prisoner looks up with fear in his eyes, but he suddenly knows that the creature is more human than it 6th +3 Eldritch Strikes, 4 seems. Influence Feature No two abominations are ever the same, endowed (or 7th +3 Bestial Strength (+2) 4 cursed, as some would say) with great power and defined by 8th +3 Ability Score Improvement 4 their abominable form. Though each appears as a normal humanoid, each possesses the ability to shapeshift into what 9th +4 — 5 can only be described as a horrific monster, an abomination 10th +4 Influence Feature 5 that is to be feared and served. -

Hulk Smash! September, 2020, Vol

Journal of Criminal Justice and Popular Culture Hulk Smash! September, 2020, Vol. 20 (Issue 1): pp. 28 - 42 Clevenger and Acquaviva Copyright © 2020 Journal of Criminal Justice and Popular Culture All rights reserved. ISSN: 1070-8286 Hulk Smash! Violence in The Incredible Hulk Comics Shelly Clevenger Sam Houston State University & Brittany L. Acquaviva Sam Houston State University 28 Journal of Criminal Justice and Popular Culture Hulk Smash! September, 2020, Vol. 20 (Issue 1): pp. 28 - 42 Clevenger and Acquaviva Abstract “Hulk smash!” is one of the most iconic phrases uttered in the pages of comic books. The Incredible Hulk is one of comics’ most violent characters as the Hulk smashes first and asks questions later. The popularity of the comic book genre has exploded within past decades and the interest in comics has increased. But exactly how violent is The Incredible Hulk and what does that mean for readers? This research examines the occurrence of violence in the Incredible Hulk comics through a thematic content analysis of 248 issues. Specifically, such themes as violence against men and women, unpunished violence, formal punishments of violence, interventions to stop violence and the justification provided for violence were assessed. The goal of the research was to determine the amount and level of violence within the comic and in what context it occurred. Results indicate that there is a large amount of violence occurring within the pages of the Incredible Hulk, but that this violence is often justified and committed by the Hulk to protect himself and others. A discussion is provided regarding the potential impact this may have on a reader and their view of violence, crime and justice. -

Research Report

1.1 CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION Soil erosion is the systematic removal of soil, including plant nutrients, from the land surface by various agents of denudation (Ofomata, 1985). Water being the dominant agent of denudation initiates erosion by rain splash impact, drag and tractive force acting on individual particles of the surface soil. These are consequently transported seizing slope advantage for deposition elsewhere. Soil erosion is generally created by initial incision into the subsurface by concentrated runoff water along lines or zones of weakness such as tension and desiccation fractures. As these deepen, the sides give in or slide with the erosion of the side walls forming gullies. During the Stone Age, soil erosion was counted as a blessing because it unearths valuable treasures which lie hidden below the earth strata like gold, diamond and archaeological remains. Today, soil erosion has become an endemic global problem, In the South eastern Nigeria, mostly in Anambra State, it is an age long one that has attained a catastrophic dimension. This environmental hazard, because of the striking imprints on the landscape, has sparked off serious attention of researchers and government organisations for sometime now. Grove(1951); Carter(1958); Floyd(1965); Ofomata (1964,1965,1967,1973,and 1981); all made significant and refreshing contributions on the processes and measures to combat soil erosion. Gully Erosion is however the prominent feature in the landscape of Anambra State. The topography of the area as well as the nature of the soil contributes to speedy formation and spreading of gullies in the area (Ofomata, 2000);. 1.2 Erosion Types There are various types of erosion which occur these include Soil Erosion Rill Erosion Gully Erosion Sheet Erosion 1.2.1 Soil Erosion: This has been occurring for some 450 million years, since the first land plants formed the first soil. -

“Things Fall Apart” in “Dead Men's Path”

International Journal of Linguistics and Literature (IJLL) ISSN(P): 2319-3956; ISSN(E): 2319-3964 Vol. 7, Issue 6, Oct - Sep 2018; 57-70 © IASET “THINGS FALL APART” IN “DEAD MEN’S PATH”, A STORY FROM CHINUA ACHEBE’S GIRLS AT WAR AND OTHER STORIES Komenan Casimir Lecturer, Department of English, Félix Houphouët-Boigny University of Coode, Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire ABSTRACT Introduced in Igbo-land owing to colonialism, Western school proves intolerant of Odinani, the Igbo traditional religion,by closing “Dead Men’s Path”, a symbol of three realms of existence: the dead, the living and the unborn children. To claim the right of being practiced freely, Odinaniwage war with the school. The ins and outs of these conflicts permits of postulating that “things fall apart” in “Dead Men’s Path”, a short story excerpted from Achebe’s Girls at War and Other Stories. KEYWORDS: “Things Fall Apart”, “Dead Men’s Path”, Intolerant School, Odinani, Igbo, Achebe Article History Received: 04 Oct 2018 | Revised: 16 Oct 2018 | Accepted: 03 Nov 2018 INTRODUCTION Introduced in Africa with the advent of colonization and its civilizing mission, school as one feature of the white man’s ways, has clashed with Odinani, the Igbo traditional religion based on the ancestral veneration or what is referred to as the first faith of Africans 1. As a result, the inherited religious practices have become obsolete, as shown in Chinua Achebe’s “Dead Men’s Path”, a short story extracted from Girls at War and Other Stories (1972). This work is a collection of short stories in which the author attests to the culturo-spiritual conflict between the African culture and the European one 2. -

Dictionary of Ò,Nì,Chà Igbo

Dictionary of Ònìchà Igbo 2nd edition of the Igbo dictionary, Kay Williamson, Ethiope Press, 1972. Kay Williamson (†) This version prepared and edited by Roger Blench Roger Blench Mallam Dendo 8, Guest Road Cambridge CB1 2AL United Kingdom Voice/ Fax. 0044-(0)1223-560687 Mobile worldwide (00-44)-(0)7967-696804 E-mail [email protected] http://www.rogerblench.info/RBOP.htm To whom all correspondence should be addressed. This printout: November 16, 2006 TABLE OF CONTENTS Abbreviations: ................................................................................................................................................. 2 Editor’s Preface............................................................................................................................................... 1 Editor’s note: The Echeruo (1997) and Igwe (1999) Igbo dictionaries ...................................................... 2 INTRODUCTION........................................................................................................................................... 4 1. Earlier lexicographical work on Igbo........................................................................................................ 4 2. The development of the present work ....................................................................................................... 6 3. Onitsha Igbo ................................................................................................................................................ 9 4. Alphabetization and arrangement..........................................................................................................