The Genesis of International Mass Migration

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Daily Report Thursday, 20 July 2017 CONTENTS

Daily Report Thursday, 20 July 2017 This report shows written answers and statements provided on 20 July 2017 and the information is correct at the time of publication (06:34 P.M., 20 July 2017). For the latest information on written questions and answers, ministerial corrections, and written statements, please visit: http://www.parliament.uk/writtenanswers/ CONTENTS ANSWERS 10 Social Tariffs: Torfaen 19 ATTORNEY GENERAL 10 Taxation: Electronic Hate Crime: Prosecutions 10 Government 19 BUSINESS, ENERGY AND Technology and Innovation INDUSTRIAL STRATEGY 10 Centres 20 Business: Broadband 10 UK Consumer Product Recall Review 20 Construction: Employment 11 Voluntary Work: Leave 21 Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy: CABINET OFFICE 21 Mass Media 11 Brexit 21 Department for Business, Elections: Subversion 21 Energy and Industrial Strategy: Electoral Register 22 Staff 11 Government Departments: Directors: Equality 12 Procurement 22 Domestic Appliances: Safety 13 Intimidation of Parliamentary Economic Growth: Candidates Review 22 Environment Protection 13 Living Wage: Jarrow 23 Electrical Safety: Testing 14 New Businesses: Newham 23 Fracking 14 Personal Income 23 Insolvency 14 Public Sector: Blaenau Gwent 24 Iron and Steel: Procurement 17 Public Sector: Cardiff Central 24 Mergers and Monopolies: Data Public Sector: Ogmore 24 Protection 17 Public Sector: Swansea East 24 Nuclear Power: Treaties 18 Public Sector: Torfaen 25 Offshore Industry: North Sea 18 Public Sector: Wrexham 25 Performing Arts 18 Young People: Cardiff Central -

Reflections on American Agricultural History*

AGHR52_1.qxd 15/06/2007 10:23 Page 1 Reflections on American agricultural history* by R. Douglas Hurt Abstract This paper reviews the contribution of American agricultural history over the twentieth century. It traces the earliest writings on the topic before the foundation of the Agricultural History Society in 1919. The discipline is reviewed under six heads: land policy including tenancy; slave institutions and post-bellum tenancy in the southern states; agricultural organizations; the development of commercial agriculture; government policy towards farming; and the recent concern with rural social history. A final section con- siders whether the lack of any definition of agricultural history has been a strength or a weakness for the discipline. The history of American agriculture as a recognized field of study dates from the early twentieth century. In 1914, Louis B. Schmidt apparently taught the first agricultural history course in the United States at Iowa State College. Schmidt urged scholars to study the history of agriculture to help government officials provide solutions to problems that were becoming increasingly economic rather than political. He believed historians had given too much attention to politi- cal, military and religious history, and Schmidt considered the economic history of agriculture a new and exciting subject for historical inquiry. Schmidt recognized the limitless topical nature of such work, because so little had been done. He urged historians to investigate land, immi- gration, tariff, currency, and banking policy, as well as organized labour, corporate regulation, slavery, and the influences of agriculture, broadly conceived, on the development of national life.1 Schmidt called on the first generation of professionally trained historians, who intended to make history more useful and relevant and whose interests often involved economic causation, to interpret the present ‘in light of economic and social evolution’. -

(Public Pack)Agenda Document for Cornwall and Isles of Scilly Local

Title: CIoS Local Enterprise Partnership Board Date: Wednesday 28 July 2021 Time: 10.00 to 13.00 Venue: : - Council Offices, Chy Trevail, Bodmin, PL31 2FR Livestream Link: https://teams.microsoft.com/l/meetup- join/19%3ameeting_NmFkNzY4NWMtNmVjMy00YTgxLWFhZTMtMDZlZDRlZGIyNTU5 %40thread.v2/0?context=%7b%22Tid%22%3a%22efaa16aa-d1de-4d58-ba2e- 2833fdfdd29f%22%2c%22Oid%22%3a%22fa9d3751-6eb5-4308-b8c3- 006db67ed9ac%22%2c%22IsBroadcastMeeting%22%3atrue%7d&btype=a&role=a Agenda Item Lead Action 1. 10.00 Welcome and Introductions Apologies for Absence Directors: Louis Mathers Officers: Phil Mason, John Curnow 2. 10.05 Declarations of Interest ALL 3. 10.10 LEP Board (31 March 2021) 3 .1 Minutes (Pages 3 - 11) MD To note 3 .2 Action Summary (Page 12) GCG To note 4. Strategic Matters 4 .1 10.20 Chair Update MD To note 4 .2 10.30 CEO Report, with a focus on: (Pages 13 - 65) GCG To note/ Labour market and skills challenges presentation Green Industrial Revolution 4 .3 11.25 Fishing Sector Update (Pages 66 - 68) MD/NC Decision Page 1 4 .4 11.50 Nominations Committee Update (Pages 69 - GCG Decision 122) 4 .5 12.15 Audit & Assurance Committee Update (Pages GCG Decision 123 - 198) 4 .6 12.25 Enterprise Zones Board Update (Pages 199 - SJ/GCG To note 202) 4 .7 12.35 Any other business 5. Exclusion of Press and Public 5 .1 12.40 Investment & Oversight Panel Update (Pages MD/GCG To note 203 - 206) 5 .2 12.50 Any other confidential business ALL Page 2 Agenda No. 3.1 Information Classification: CONTROLLED CORNWALL AND ISLES OF SCILLY LOCAL ENTERPRISE PARTNERSHIP MINUTES of a Meeting of the Cornwall and Isles of Scilly Local Enterprise Partnership held in the Online - Virtual Meeting on Wednesday 31 March 2021 commencing at 10.00 am. -

A Unified Concept of Population Transfer

Denver Journal of International Law & Policy Volume 21 Number 1 Fall Article 4 May 2020 A Unified Concept of opulationP Transfer Christopher M. Goebel Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.du.edu/djilp Recommended Citation Christopher M. Goebel, A Unified Concept of Population Transfer, 21 Denv. J. Int'l L. & Pol'y 29 (1992). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ DU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Denver Journal of International Law & Policy by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ DU. For more information, please contact [email protected],[email protected]. A Unified Concept of Population Transfer CHRISTOPHER M. GOEBEL* Population transfer is an issue arising often in areas of ethnic ten- sion, from Croatia and Bosnia and Herzegovina to the Western Sahara, Tibet, Cyprus, and beyond. There are two forms of human population transfer: removals and settlements. Generally, commentators in interna- tional law have yet to discuss the two together as a single category of population transfer. In discussing the prospects for such a broad treat- ment, this article is a first to compare and contrast international law's application to removals and settlements. I. INTRODUCTION International attention is focusing on uprooted people, especially where there are tensions of ethnic proportions. The Red Cross spent a significant proportion of its budget aiding what it called "displaced peo- ple," removed en masse from their abodes. Ethnic cleansing, a term used by the Serbs, was a process of population transfer aimed at removing the non-Serbian population from large areas of Bosnia-Herzegovina.2 The large-scale Jewish settlements into the Israeli-occupied Arab territories continue to receive publicity. -

Mass Displacement in Post-Catastrophic Societies: Vulnerability, Learning, and Adaptation in Germany and India, 1945–1952

Futures That Internal Migration Place-Specifi c Introduction Never Were and the Left Material Resources MASS DISPLACEMENT IN POST-CATASTROPHIC SOCIETIES: VULNERABILITY, LEARNING, AND ADAPTATION IN GERMANY AND INDIA, 1945–1952 Avi Sharma The summer of 1945 in Germany was exceptional. Displaced persons (UN DPs), refugees, returnees, ethnic German expellees (Vertriebene)1 and soldiers arrived in desperate need of care, including food, shelter, medical attention, clothing, bedding, shoes, cooking utensils, and cooking fuel. An estimated 7.3 million people transited to or through Berlin between July 1945 and March 1946.2 In part because of its geographical location, Berlin was an extreme case, with observers estimating as many as 30,000 new arrivals per day. However, cities across Germany were swollen with displaced persons, starved of es- sential supplies, and faced with catastrophic housing shortages. During that time, ethnic, religious, and linguistic “others” were frequently conferred legal privileges, while ethnic German expellees and internally displaced persons (IDPs) were disadvantaged by the occupying forces. How did refugees, returnees, DPs, IDPs and other migrants navigate the fractured governmentality and allocated scar- city of the postwar regime? How did survivors survive the postwar? The summer of 1947 in South Asia was extraordinary in diff erent ways.3 Faced with a hastily organized division of the Indian sub- continent into India and Pakistan (known as the Partition), between 10 and 14 million Muslims, Sikhs, and Hindus crossed borders in a period of only a few months. Estimates put the one-day totals for 2 Angelika Königseder, cross-border movement as high as 400,000, and data on mortality Flucht nach Berlin: Jüdische Displaced Persons 1945– 4 range between 200,000 and 2 million people killed. -

The Cornwall and Isles of Scilly Local Enterprise Partnership (LEP) Was Launched in May 2011

Written evidence submitted by Cornwall and Isles of Scilly Local Enterprise Partnership (INS0039) The Cornwall and Isles of Scilly Local Enterprise Partnership (LEP) was launched in May 2011. Private sector-led, it is a partnership between the private and public sectors and is driving the economic strategy for the region, determining local priorities and undertaking activities to drive growth and the creation of local jobs. Executive Summary The Government’s Industrial Strategy should be refreshed to include wider economic, social and environmental factors that are now in play post Covid 19 by building on all of England’s Local Industrial Strategies. Industrial Strategy Grand Challenges should be updated and localised, within a national framework, and should consider the levelling up agenda, climate change, regional imbalances and measures to reduce inequality/social inclusion. The refresh should use the guiding principle of devolving decision making and delivery. The focus on key sectors in the current Industrial Strategy is sufficient if a narrow view on “growth” is used or if “trickle down” economic policies are adopted. However, whilst this approach will raise the productivity and growth of some areas it will not benefit all areas equally and those areas furthest from key industrial centres will see little or no benefit. As the future prosperity of the UK depends on unlocking the potential of all its areas, towns, high streets businesses and residents the revised Industrial Strategy needs to be more inclusive and allow for different areas to make different contributions to overall productivity levels and growth. The immense productivity gap that currently exists between the prosperous South East of England and the rest of the country on the other must be therefore be levelled-up by investing in the LEP areas that are currently lagging behind. -

Corporate Business Plan 2016/17 – 2019/20

Business Plan 2016 - 2020 Delivering our Strategy www.cornwall.gov.uk Contents Page Foreword 2 1. Introduction 3 1.1 Our Strategy 3 1.2 Context 4 1.3 Our Corporate Business Plan 5 2. Progress to date – Strategic Overview: 6 Incorporates updates on the ‘Ambitious Cornwall’, ‘Engaging with our communities’ and ‘Partners working together’ strategic aims 3. Delivering the Council Strategy: Greater access, Driving the 10 economy, Stewarding the assets 3.1 Strategy, Economy, Enterprise & Environment 10 3.2 Commissioning & Asset Management 15 3.3 Planning & Enterprise 19 4. Delivering the Council Strategy: Healthier and safe 22 communities 4.1 Children’s Early Help, Psychology & Social Care 22 4.2 Commissioning Performance & Improvement 25 4.3 Adult Care & Support 29 4.4 Public Health 32 4.5 Learning and Achievement 35 4.6 Fire, Rescue and Community Safety 38 4.7 Public Protection 39 5. Delivering the Council Strategy: Being efficient, effective 45 and innovative 5.1 Customers and Communities 45 5.2 Business Planning & Development / People Management, 48 Development & Wellbeing 5.3 Governance and Information 51 6. Managing the Plan 54 6.1 Business & Service Planning 54 6.2 Performance management and reporting 55 6.3 Management of risk 55 6.4 Organisational development framework 56 7. Financial Resources 58 8. Conclusion 59 9. Acronyms 60 Corporate Business Plan 2016/17 – 2019/20 JOINT FOREWORD Welcome to the Council’s Business Plan for the next four years. When we approved our Council Strategy in 2014 we knew that we would be facing some significant challenges over the course of this decade, but also that there were tremendous opportunities for both the Council and for Cornwall if we worked with colleagues in the public, private and community sectors to deliver our ambition of creating a more sustainable and prosperous Cornwall that is resilient and resourceful, a place where communities are strong and where the most vulnerable are protected. -

Forced Population Transfers Resolve Self-Determination Conflicts?

Can Forced Population Transfers Resolve Self-determination Conflicts? A European Perspective Stefan Wolff Department of European Studies University of Bath Bath BA2 7AY England, UK [email protected] Introduction Self-determination conflicts are among the most violent forms of civil wars that can engulf modern societies. As they are in most cases linked to claims of ethnic, religious, linguistic or otherwise defined groups for secession from, or for political domination in, an existing state they also have repercussions on regional and international stability. Self-determination conflicts can be observed on all continents. Not all of them are violent, but most have a clear potential for violent escalation and are therefore an important concern for international and regional governmental organisations seeking to preserve peace and stability. However, the capacity of organisations like the UN, the OSCE and the EU to do so has only gradually developed over the past decade and is still a far cry from being sufficient. In the past and present, states (and population groups within them) have therefore felt that they had been and are left to their own devices when it comes to preserving their internal stability and external security. The largely incongruent political and ethnic maps of Europe have meant that self- determination conflicts on this continent have mostly taken the form of ethnic conflicts: from Northern Ireland to the Caucasus, from the Basque country to the Åland islands and from Kosovo to Silesia the competing claims of distinct ethnic groups to self-determination have been the most prominent sources of conflicts within and across state boundaries. -

Indicators for Monitoring the Un Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples

INDICATORS FOR MONITORING THE UN DECLARATION ON THE RIGHTS OF INDIGENOUS PEOPLES A solid framework and a practical tool for assessing the implementation of UNDRIP’s provisions. The indicators serve to detect gaps in implementation, hold duty-bearers accountable, and devise implementation strategies. 1 WHAT IS THE INDIGENOUS NAVIGATOR? The Indigenous Navigator comprises a set of tools for monitoring indigenous peoples’ rights and development. One of these tools is a set of indicators, which serve to pinpoint what to look for when measuring whether the provisions of UNDRIP are implemented in a given community or country. The indicators are structured around 13 thematic domains reflected in UNDRIP and have been systematically developed with a solid foundation in the OHCHR’s methodology for developing human rights indicators.1 Like all other human rights instruments, UNDRIP comprises standards on specific rights and cross-cutting human rights norms. The first step towards identifying the indicators has therefore been to identify the attributes – or building blocks – contained in UNDRIP. Subsequently, measurable indicators have been identified with a view to capturing States’ duties to respect, protect and fulfil indigenous peoples’ human rights. The indicators framework comprises: Structural indicators, which assess the legal and policy framework of a given country. Process indicators, which measure the states’ ongoing efforts to implement human rights commitments through programs, budget allocations, etc. Outcome indicators, which capture the actual enjoyment of human rights by indigenous peoples. The indicators can also be used to measure essential aspects of the SDGs as well as the commitments made by States at the 2014 World Conference on Indigenous Peoples. -

ERDF Convergence Progress Report, Jun 2014 DRAFT.Pub

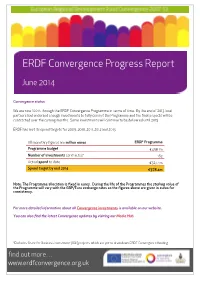

ERDF Convergence Progress Report June 2014 Convergence status We are now 100% through the ERDF Convergence Programme in terms of time. By the end of 2013 local partners had endorsed enough investments to fully commit the Programme and the final projects will be contracted over the coming months. Some investments will continue to be delivered until 2015. ERDF has met its spend targets for 2009, 2010, 2011, 2012 and 2013. All monetary figures are million euros ERDF Programme Programme budget €458.1m Number of investments contracted* 163 Actual spend to date €327.4m Spend target by end 2014 €378.4m Note: The Programme allocation is fixed in euros. During the life of the Programmes the sterling value of the Programme will vary with the GBP/Euro exchange rates so the figures above are given in euros for consistency. For more detailed information about all Convergence investments is available on our website. You can also find the latest Convergence updates by visiting our Media Hub. *Excludes Grant for Business Investment (GBI) projects which are yet to draw down ERDF Convergence funding. find out more… www.erdfconvergence.org.uk CONVERGENCE INVESTMENTS New Investments Apple Aviation Ltd Apple Aviation, an aircraft maintenance, repair and overhaul company, has established a base at Newquay Airport’s Aerohub. Convergence funding from the Grant for Business Investment programme will contribute to salary costs for thirteen new jobs in the business. ERDF Convergence investment: £211,641 (through the GBI SIF) Green Build Hub Located alongside the Eden Project, the Green Build Hub will be a research facility capable of demonstrating and testing the performance of innovative sustainable construction techniques and materials in a real building setting. -

The Cultural Heritage of Indigenous Peoples and Its Protection: Rights and Challenges

The cultural heritage of indigenous peoples and its protection: rights and challenges Based on presentations of the International Expert Seminar of the Saami Cultural Heritage Week, organized by the Saami Council in Rovaniemi, October 27•28, 2008. Contents 1 Cultural heritage 1 1.2 Misappropriation of the cultural heritage of indigenous peoples 2 1.3 How to protect the cultural heritage of indigenous peoples? 3 1.3.1 Self•determination and free, prior and informed consent 4 2 General UN instruments relevant for the cultural heritage of indigenous peoples 5 2.1 The International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights 5 2.2 The International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights 6 2.3 The Universal Declaration on Human Rights 6 2.4 The Convention on the Elimination of all Forms of Racial Discrimination 6 3 The UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples 7 3.1 Non•discrimination 7 3.2 Self•determination 8 3.3 Indigenous peoples have to be seen as indigenous 9 3.4 Indigenous peoples and land rights 9 3.5 Culture 10 3.6 Recognition of indigenous peoples’ own institutions 11 3.7 Procedures 12 4 Other relevant international organizations and instruments 13 4.1 The World Intellectual Property Organization 13 4.1.1 The Intergovernmental Committee on Intellectual Property, Genetic Resources, Traditional Knowledge and Folklore 13 4.2 The ILO Convention No. 169 14 4.3 UNESCO 15 4.3.1 The Declaration on Cultural Diversity 16 4.3.2 The Convention on the Protection and Promotion of the Diversity of Cultural Expressions 17 4.4 The Convention on Biological Diversity 17 4.5 The American Declaration of the Rights and Duties of Man 19 5 Suggestions and best practices 19 5.1 Review of the draft principles and guidelines on the heritage of indigenous peoples 21 References 22 This document is based on the material from the International Expert Seminar of the Saami Cultural Heritage Week organized by the Saami Council in Rovaniemi October 27•28, 2008. -

Maltese Immigrants in Detroit and Toronto, 1919-1960

Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports 2018 Britishers in Two Worlds: Maltese Immigrants in Detroit and Toronto, 1919-1960 Marc Anthony Sanko Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd Recommended Citation Sanko, Marc Anthony, "Britishers in Two Worlds: Maltese Immigrants in Detroit and Toronto, 1919-1960" (2018). Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports. 6565. https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd/6565 This Dissertation is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by the The Research Repository @ WVU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Dissertation in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you must obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Dissertation has been accepted for inclusion in WVU Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports collection by an authorized administrator of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Britishers in Two Worlds: Maltese Immigrants in Detroit and Toronto, 1919-1960 Marc Anthony Sanko Dissertation submitted to the Eberly College of Arts and Sciences at West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History Kenneth Fones-Wolf, Ph.D., Chair James Siekmeier, Ph.D. Joseph Hodge, Ph.D. Melissa Bingmann, Ph.D. Mary Durfee, Ph.D. Department of History Morgantown, West Virginia 2018 Keywords: Immigration History, U.S.