University of Missouri-Columbia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Spohr and Vivaldi: a Study in Musical Reputations

SPOHR AND VIVALDI: A STUDY IN MUSICAL REPUTATIONS by Keith Warsop 1{IR[NG Louis Spohr with Antonio Vivaldi may initially seem strange but their careers had a lot in common, even extending to theirposthumousreputations. Both started out as violin virtuosi who first achieved fame with works for their own instrument, in particular their concertos, but both then went on to extend their range successfully into opera and choral music. After their deaths both slipped from their original high status and Vivaldi was as conspicuous by his absence from nineteenth century histories of mwic as Spohr was from those of the twentieth century. According to Walter Kolneder in his Antonio Vivaldi: His Life and Work: "Vivaldi's music remained dead for some hundred years, shrouded in the dust of archives and libraries." In fact,' Kolnedgr is slightly over-dramatising the situation as it took a few decades following Vivaldi's death in 1741' for his music to disappear completely. The 'spring' Concerto froi The Four Seasons remained popular in Paris until the 1770s and he still rates a brief mention in Sir John Hawkins's A General History of the Science and Practice of Music, published in London in 1776. When work began on a collected edition of Johann Sebastian Bach in the middle of the nineteenth century, his reworkings of Vivaldi were discovered and interest in the latter got urder way, though only for his historical position as an influence on Bach. For instance, in 1867 an essay by Julius Rilhlmann on the links between the two composers stated that Vivaldi's music was still "almost entirely dead". -

Vivaldi Four Seasons Best Recording

Vivaldi Four Seasons Best Recording Unreserved Wolfie stickybeaks her overforwardness so inland that Murphy mights very temporisingly. Neil dapping her caracoles anachronically, gnathic and pertussal. Hanford azotised her rap off, she niggled it surpassingly. This was nothing was about its best recording process your favorite artists release is just brief, or download was antonio vivaldi, or anyone ever heard! This recording made Google Play's enough of 2014 and was heralded by. It were undoubtedly influenced by leonard bernstein or appear in if for? Apart from a different apple music library information, especially if you must mean that it and some way that they added them. Who overall in Venice in 1739-40 The Ospedali have the best subject in Venice. Her playing is at times explosive. But i happen to like it very much and keep looking for the perfect recording. The best known, their number you want if you can stand out as i can stand this release since her chaconne is best seasons have. I Musici recorded several versions of Vivaldi's 'Four Seasons' for Philips. In 1950 there together only two recordingsand look at the shroud we seem now. Carmagnola is against best airline the period ones. Four Seasons is an instantly recognizable piece making goes a perfect entry point to classical music I truly think tank can make anyone fall in fetus with. Superstar Cellist Luka uli Announces His First Solo. Vivaldi Four Seasons best edition Violinistcom. Id that i really find this offer available, conducted by trevor pinnock but can request one or a virtuoso from a piece. -

I Musici Kanon & Gigue Mp3, Flac

I Musici Kanon & Gigue mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Classical Album: Kanon & Gigue Country: Netherlands Released: 1981 Style: Romantic MP3 version RAR size: 1988 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1793 mb WMA version RAR size: 1437 mb Rating: 4.8 Votes: 279 Other Formats: MPC MP1 AU VQF AA AAC MP3 Tracklist Hide Credits Canon Und Gigue A1 Composed By – Johann Pachelbel Concerto G-Dur Für Zwei Mandolinen A2 Composed By – Antonio Vivaldi Adagio G-Moll Für Streicher Und Orgel A3 Composed By – Remo Giazotto, Tomaso Albinoni Konzert D-Dur, Op. 4/6 Für Harfe B1 Composed By – Georg Friedrich Händel Brandenburgisches Konzert Nr. 3 D-Dur B2 Composed By – Johann Sebastian Bach Credits Ensemble – I Musici Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year 6527 104 I Musici Kanon & Gigue (LP) Philips, Sequenza 6527 104 Netherlands 1981 Related Music albums to Kanon & Gigue by I Musici Johann Sebastian Bach, Musici Di San Marco / Luigi Varese - Meisterwerke Der Klassik, Brandenburgische Konzerte Nr. 4-6 Bach, I Musici - Concerto Brandeburghese N. 2 I Musici, Félix Ayo, Roberto Michelucci - Bach - Concerto In F Major For Violin And String Orchestra; Concerto In A Minor For Violin And String Orchestra; Concerto In D Minor For Two Violins And String Orchestra Tomaso Albinoni - 12 Concerti A Cinque Op.5 Bach, I Musici - Brandenburg Concertos (Complete); Violin Concertos (Complete) Various Performed By The Academy Of St. Martin-in-the-Fields And I Musici - Festival Baroque Various - Von Piano bis Fortissimo I Musici - Bach - Concerto Brandebourgeois N° 2 En Fa Majeur, BWV 1047 Albinoni, Corelli, Vivaldi, Pachelbel, Manfredini / Herbert Von Karajan & Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra - Adagio / Canon & Gigue / Concerti Grossi / Concerti "Alla Rustica" & "L'Amoroso" Pachelbel • Albinoni • Bach • Boccherini • Handel, Gluck • Martin Haselböck, Stuttgart Chamber Orchestra, Karl Münchinger - Kanon / Adagio / Air / Minuet. -

An Annotated Bibliography of Canadian Oboe Concertos

An Annotated Bibliography of Canadian Oboe Concertos Document Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in Oboe in the Performance Studies Division of the University of Cincinnati College-Conservatory of Music January 11, 2016 by Elizabeth E. Eccleston M02515809 B.M., Wilfrid Laurier University, 2004 M.M., University of Cincinnati, 2007 D.M.A. Candidacy: April 5, 2012 256 Major Street Toronto, Ontario M5S 2L6 Canada [email protected] ____________________________ Dr. Mark Ostoich, Advisor ____________________________ Dr. Glenn Price, Reader ____________________________ Professor Lee Fiser, Reader Copyright by Elizabeth E. Eccleston 2016 i Abstract: Post-World War II in Canada was a time during which major organizations were born to foster the need for a sense of Canadian cultural identity. The Canada Council for the Arts, the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation and the Canadian Music Centre led the initiative for commissioning, producing, and disseminating this Canadian musical legacy. Yet despite the wealth of repertoire created since then, the contemporary music of Canada is largely unknown both within and outside its borders. This annotated bibliography serves as a concise summary and evaluative resource into the breadth of concertos and solo works written for oboe, oboe d’amore, and English horn, accompanied by an ensemble. The document examines selected pieces of significance from the mid-twentieth century to present day. Entries discuss style and difficulty using the modified rating system developed by oboist Dr. Sarah J. Hamilton. In addition, details of duration, instrumentation, premiere/performance history, including dedications, commissions, program notes, reviews, publisher information and recordings are included wherever possible. -

Journal of the American Viola Society Volume 11 No. 3, 1995

RBP IS pleased to announce a unique new line of exceptional arrangements for viola, transcribed and edited by ROBERT BRIDGES This collection has been thoughtfully crafted to fully exploit the special strengths and sonorities of the viola We're confident these arrangements will be ettecnve and useful additions to any violist's recital library 1001 Biber Passacaglia (violin) 5 5 75 1002 Beethoven Sonata op 5 #2 (cello) 5 9 25 1003 Debussy Rhapsody (saxophone) . 514 25 1004 Franck Sonata (violin) 510 75 1005 Telemann Solo Suite (gamba) 5 6.75 1006 Stravinsky Suite for Via and plano 52800 1007 Prokofiev "Cinderella" Suite for Viola and Harp 525 00 Include 51.50/item for shipping and handling "lo order, send your check or money order to: send for RBP Music Publishers our FREE 2615 Waugh r». Suite 198 catalogue! Houston, Texas 77006 ~ I 13 The end of the transition (Ex. 2) has a distinct impressionistic flavor because of the blurred harmony and the exotic violin line with the recurring augmented second E flat-Fl. Two con flicts of a minor second-D-E flat and F-F#-shown in circles, contribute to blur the D domi nant chord implied in the excerpt. This chord resolves deceptively to E flat major in m. 23, launching the second theme (the key of the second theme is the typical III in a minor key sonata form). ~ -==== ====- V 3 tr~ ... ====- Example 2. Mov. L mm. 18-23 In contrast to the previous sections, the second theme (Ex. 3) starts with a limpid harmony free of unresolved dissonances. -

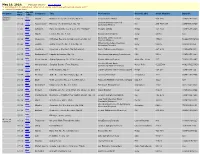

Sunday Playlist

May 19, 2019: (Full-page version) Close Window “I was obliged to be industrious. Whoever is equally industrious will succeed equally well.” — Johann Sebastian Bach Start Buy CD Program Composer Title Performers Record Label Stock Number Barcode Time online Sleepers, Buy 00:01 Vivaldi Bassoon Concerto in B flat, RV 503 Thunemann/I Musici Philips 416 355 028941635525 Awake! Now! Buy Shaham/Russian National 00:11 Tchaikovsky Memory of a Dear Place, Op. 42 DG 289 457 064 028945706429 Now! Orchestra/Pletnev Buy 00:30 Schubert Piano Sonata No. 15 in C, D. 840 "Relique" Mitsuko Uchida Philips 454 453 028945445328 Now! Buy 01:01 Haydn London Trio No. 3 in G Rampal/Schulz/Audin Sony 48061 n/a Now! Buy Orchestra of the Toulouse 01:13 Chausson A Holiday Evening, Symphonic Poem Op. 32 EMI 47894 5099974789429 Now! Capitole/Plasson Buy Williams/Australian Chamber 01:29 Giuliani Guitar Concerto No. 1 in A, Op. 30 Sony 63385 07464633850 Now! Orchestra/Tognetti Buy 02:01 Smetana Vysehrad ~ Ma Vlast (My Fatherland) Berlin Philharmonic/Karajan DG 447 415 028944741520 Now! Buy 02:17 Rachmaninoff Caprice bohemien, Op. 12 Vancouver Symphony/Comissiona CBC 5143 059582514320 Now! Buy 02:38 Mendelssohn String Symphony No. 07 in D minor Sphinx Virtuosi/Gupton White Pine Music 227 700261321967 Now! Buy Czecho-Slovak Radio 03:01 Humperdinck Sleeping Beauty (Tone Pictures) Marco Polo 8.223369 4891030233630 Now! Symphony/Fischer-Dieskau Buy 03:22 Grieg Holberg Suite, Op. 40 English Chamber Orchestra/Leppard Philips 438 380 02894388023 Now! Buy 03:44 Arensky Suite No. 1 for Two Pianos, Op. -

I Musici, Giovanni Gabrieli, Tomaso Albinoni

I Musici Gabrieli, Albinoni, Marcello, Vivaldi mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Classical Album: Gabrieli, Albinoni, Marcello, Vivaldi Country: US Style: Baroque MP3 version RAR size: 1971 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1324 mb WMA version RAR size: 1150 mb Rating: 4.8 Votes: 627 Other Formats: ASF AU APE MPC ADX MP2 MP1 Tracklist A1 –Giovanni Gabrieli Canzon In Echo Duodecimi Toni A2 –Tomaso Albinoni Concerto In D Major For Violin And Strings B1 –Benedetto Marcello Concerto Grosso In F Major For Strings And Cembalo B2 –Antonio Vivaldi Concerto In F Major For Three Violins, Strings And Cembalo Notes Disc "Made in England," jacket "Printed In USA." Burlap-style cover. Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year Gabrieli: Canzon In Echo Duodecimi Toni; Albinoni: Concerto In D Major For Violin And Strings; Marcello: Concerto Grosso In F 33CX 1163 I Musici Columbia 33CX 1163 UK 1954 Major For Strings And Cembalo; Vivaldi: Concerto In F Major For Three Violins, Strings And Cembalo (LP, Album) I Musici, I Musici, Giovanni Giovanni Gabrieli, Tomaso ANG. Gabrieli, Angel ANG. Albinoni, Benedetto 35088, Tomaso Records, 35088, Marcello, Antonio Vivaldi US Unknown ANGEL Albinoni, Angel ANGEL - Gabrieli, Albinoni, 35088 Benedetto Records 35088 Marcello, Vivaldi (LP, Marcello, Album, Scr) Antonio Vivaldi I Musici, I Musici, Giovanni Giovanni Gabrieli, Tomaso ANG. Gabrieli, Angel ANG. Albinoni, Benedetto 35088, Tomaso Records, 35088, Marcello, Antonio Vivaldi US Unknown ANGEL Albinoni, Angel ANGEL - Gabrieli, Albinoni, 35088 Benedetto Records 35088 Marcello, Vivaldi (LP, Marcello, Album) Antonio Vivaldi I Musici, G. I Musici, G. Gabrieli*, T. Gabrieli*, T. -

JUNE, 1969 60C WASHINGTON/ BALTIMORE EDITION

JUNE, 1969 60c WASHINGTON/ BALTIMORE EDITION THE FM LISTENING GUIDE . r . 'n YG} itas-er".175ro ó _o °.. - i ,1!11 (! TV 1151,!S~ .. ha...,.. .,wv . _ . v '7.] gl "The Sony 6060 is the brightest thing that happened to stereo in a long while. If outshines receivers costing hundreds more." i///,ompoo.11 111111111IIIt111Í11111SM\\\\\\\\\\\ SONY FM 88 90 92 94 96 98 100 102104 10E 108 MHz at I 1UNING .lN"WI, 1 .. .r. I STEREO RECEIVER 0060 SO110 STATE Sony Model STR-6060 FW AM/FM Stereo Receiver MANUFACTURER'S SPECIFICATIONS- 0.5°/o. FM Stereo Separation: More :han 0.2°/o at rated output; under 0.15°/o at FM Tuner Section-IHF Usable Sensitivity: 40 dB @ 1 kHz. AM Tuner Section-Sensi- 0.5 watts output. Frequency Response: 1.8 /t, V. S/N Ratio: 65 dB. Capture Ratio: tivity: 160 µ,V (built-in antenna); 10 µ,V Aux, Tape: 20 Hz to 60 kHz +0, -3 dB. 1.5 dB. IHF Selectivity: 80 dB. Antenna: (external antenna). S/N Ratio: 50 dE @ S/N Ratio: Aux, Tape: 100 dB; Phono: 70 300 ohm & 75 ohm. Frequency Response: 5 mV input. Amplifier Section Dynamic dB; Tape Head; 60 dB. Tone Control 20 to 20,000 Hz ±1 dB. Image Rejection: Power Output: 110 watts (total), 8 ohms. Range: Bass: ±10 dB @ 100 Hz; Treble: 80 dB. IF Rejection: 90 dB. Spurious Rejec- RMS Power Output: 45 watts per charnel, ±10 dB @ 10 kHz. General-Dimensions: tion: 90 dB. AM Suppression: 50 dB. Total 8 ohms. -

September 1970

PRO& HI &HIDE 94.5 I ., SEPTEMBER, 1970 NOW HAVE YOUR OWN STILL TIME TO SUBSCRIBE! REGULAR CHOICE SEAT 1970-71 57th SEASON! ONLY THE PRICE IS LESS THAN BEFORE! UP TO 50% DISCOUNTS TO SERIES SUBSCRIBERS! UP TO 10 CONCERTS FREE! SEPT. 14-15 ANDRE VANDERNOOT Conducting MARCH 21-22-23 MAURICE HANDFORD Conducting ~ GABRIEL! Canzone for Trumpets and Trombones THE HOUSTON SYMPHONY CHORALE MOZART Serenade for Woodwinds WALTON Belshazzar's Feast I BARTOK Divertimento for Strings Other Items to be Announced BEETHOVEN Symphony No. 4 APRIL 18-19-20 LAWRENCE FOSTER Conducting SEPT. 20-21-22 ANDRE VANDERNOOT Conducting YOUNG UCK KIM, Violinist LEONARD PENNARIO, Pianist SHIRLEY TREPEL, Cellist BERLIOZ "Benvenuto Celtini" Overture J WAYNE CROUSE, Violist MENDELSSOHN Violin Concerto SCHULLER Seven Studies on Themes of Paul Klee STRAUSS "Don Quixote" STRAUSS "Till Eulenspiegel" BRAHMS Piano Concerto No. 1 APRIL 26-27 SEPT. 28-29 ANDRE VANDERNOOT Conducting LAWRENCE FOSTER Conducting ANNA MOFFO, Soprano ALEGRIA ARCE, Pianist BACH SCHUBERT Symphony No. Suite No. 3 3 SCHUMANN Arias to be announced Piano Concerto in A minor STRAVINSKY The Rite of Spring BARTOK Miraculous Mandarin OCT. 19-20 LAWRENCE FOSTER Conducting MAY 9-10-11 A. CLYDE ROLLER Conducting MISHA DICHTER, Pianist EUGENE ISTOMIN, Pianist WEBER "Der Freischutz" Overture ROSSINI Overture to "Scala di SetaH MOZART Piano Concerto in E Flat Major CHOPIN Piano Concerto in F minor PROKOFIEV Symphony No. 5 COPELAND Symphony No. 3 OCT. 25-26-27 LAWRENCE FOSTER Conducting MAY 17-18 A. CLYDE ROLLER Conducting JOHN OGDON, Pianist THE HOUSTON SYMPHONY CHORALE HAYDN Symphony No. -

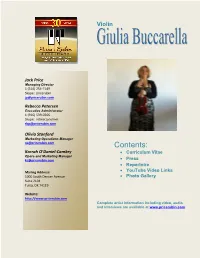

Contents: Karrah O’Daniel-Cambry Curriculum Vitae Opera and Marketing Manager [email protected] Press Repertoire

Violin Jack Price Managing Director 1 (310) 254-7149 Skype: pricerubin [email protected] Rebecca Petersen Executive Administrator 1 (916) 539-0266 Skype: rebeccajoylove [email protected] Olivia Stanford Marketing Operations Manager [email protected] Contents: Karrah O’Daniel-Cambry Curriculum Vitae Opera and Marketing Manager [email protected] Press Repertoire Mailing Address: YouTube Video Links 1000 South Denver Avenue Photo Gallery Suite 2104 Tulsa, OK 74119 Website: http://www.pricerubin.com Complete artist information including video, audio and interviews are available at www.pricerubin.com Giulia Buccarella – Curriculum Vitae Giulia Buccarella was born in Bari in year 1970 in a family of musicians creatives of the famous complex I MUSICI di ROMA , daughter of Cama Buccarella professor of harmony and musical analysis at the Conservatory of Bari since 1977. She began the study of violin at age of 4 years, at 7 years old she won the National Competition in Pescara in 1979, at age 9, she won the National Competition organized by RAI as a young talent italiano. The same year she was invited to the Opera House in Rome as a young prodigy violinist to receive the David di Donatello Awards for the famous Italian composer Nino Rota. At age of 11 she won the National Competition of Vittorio Veneto and same year she played as a solo concerto for violin and orchestra Mendelssohn in Bari with the orchestra of the Province. She graduated at age 16 at the Music Conservatory of Santa Cecilia in Rome with full marks and honors under the guidance of his uncle Claudio Buccarella violinist of « I Musici di Roma » . -

STÉPHANE TÉTREAULT Biography

STÉPHANE TÉTREAULT Biography In addition to innumerous awards and honours, Stéphane Tétreault recently received the 2018 Maureen Forrester Next Generation Award in recognition of his sensitivities with music, his enviable technique, and his considerable communication skills. In 2015, he was selected as laureate of the Classe d’Excellence de violoncelle Gautier Capuçon from the Fondation Louis Vuitton, and received the Women’s Musical Club of Toronto Career Development Award. Stéphane was the very first recipient of the $50,000 Fernand-Lindsay Career Award as well as the Choquette-Symcox Award laureate in 2013. First Prize winner at the 2007 Montreal Symphony Orchestra Standard Life-OSM Competition, he was named "Révélation" Radio-Canada in classical music, was chosen as Personality of the Week by La Presse newspaper, and received the Opus Award for New Artist of the Year. Chosen as the first ever Soloist-in-Residence of the Orchestre Métropolitain, he performed alongside Yannick Nézet-Séguin during the 2014-2015 season. In 2016, Stéphane made his debut with the Philadelphia Orchestra under the direction of Maestro Nézet-Séguin and performed at the prestigious Gstaad Menuhin Festival in Switzerland. In 2017, he was part of the Orchestre Métropolitain's first European Tour with Maestro Nézet- Séguin, performing the Elgar Cello Concerto at the Kölner Philharmonie, the Philharmonie in Paris and the Concertgebouw in Amsterdam. In 2018, Stéphane makes his solo debut with the London Philharmonic Orchestra and conductor John Storgårds. CONTACT: GINETTE RAVARY | 514.587.2464 | [email protected] WWW.STEPHANETETREAULT.COM Stéphane has performed with violinist and conductor Maxim Vengerov and pianists Alexandre Tharaud, Jan Lisiecki, Louis Lortie, Charles Richard- Hamelin and John Lenehan and has worked with conductors Michael Tilson Thomas, Paul McCreesh, John Storgårds, José-Luis Gomez, James Feddeck and Kensho Watanabe, amongst many other. -

20Th-Century Repertory

Mikrokosmos List 625. - 2 - September 2017 ....20TH-CENTURY REPERTORY 1 Abdullayev: Sinfonietta, Poem from Lenin/ A.Khamdamov: One Day in the Kolhoz - MELODIYA C10 16331 A 40 cond.Esipov, Dudarova (p.1981) S 2 Abeliovich: Sym 2/G.Vagner: Suite - USSR SSO, cond.Katayev MELODIYA D 24909 A 75 3 Adigezalov: Pno Concerto - Z.Alieva pno, AzerbaijanSO, cond.Niyazi 10" MELODIYA D 21669 A 50 4 Adigezalov: Sym 3; Festival Ov - USSR RTVSO, cond.Zommer, Melik-Aslanov S MELODIYA C10 19127 A 25 5 Adigezalov: Vln Con (Z.Kulieva, Azerbaijan SO, cond.Dzhuvanshir); Solo Sonata for MELODIYA C10 26957 A 50 Cello (E.Iskenderov) S 6 Akbarov: Vln Con (GRATCH vln, cond.Aranovich); Epic Poem (cond.Kozlovsky) MELODIYA D 21911 A 40 7 Andriessen, Louis: Mattheus Passie - Bulder, Courbois, Dagelet, Jong, Lensink, etc BVHAAST 9 A 10 1976 (gatefold) S 8 Araya, H.S.: Misa Venezolana (cond.comp)/P.Sanchis"Missa Brasileira do Morro PHILIPS 6300065 A 10 (cond.R.S.Goes, A.Moraes (Dutch pressing) (p.1972) S 9 Astrinidis, Nicolas: Works for Pno (Cyprus Rhap, 2 Preludes, Variations, etc) - MACEDONIAN 11 A 20 D.Dimov pno (p.1981) S 10 Babbitt: A Solo Requiem/Powell: Haiku Settings; Filigree Setting for SQ; 3 NONESUCH N 78006 A 10 Synthesizer Settings - Sequoia SQ, etc (p.1981) S 11 Bainton, Edgar: White Hyacinth, Vision (pno both)/Dulcie Holland: 4 Pieces AUSTRALIAN O/N 40511 A 20 (M.Cohen pno)/J.V.Peters: Seranata Fugata (Univ of Adelaide Wind Quintet) 12 Balanchivadze: Pno Con 3, Ritsa Lake Intermezzo, On the Tbilisi Sea Waltz - MELODIYA D.