Chimney Rock

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

November 9, 2015 Kid Scoop News Featured Apps This Week's

November 9, 2015 Kid Scoop News Greetings! This Week's Programs The Fight for Fort Hatteras - Chapter 4 On site This eight-chapter story takes place on the Outer Banks of North Carolina. It follows two young girls and their friends as they learn about the Civil War, its causes and a battle that took place in their community. Made from Scratch - Chapter 9 Catch up with Kentucky's two favorite Featured Apps canines that are at it again! Woody and This week's featured Chloe attend a neighborhood auction, app is Formulua where Woody purchases a disco ball. Free - Formulas for Unsure what a disco ball is, the pups Calculus. (High School) decide to do some research. Have you ever needed to know that one math formula that you always Pigskin Geography Kickoff forget? Do This week's quiz topics cover: you spend minutes flipping through your Study of many peninsulas textbook or Holland Tunnel under the Hudson River searching the Robert Fulton and the Clermont on the Hudson River internet for it? Then you need Soldier Field, World War I and World War II Formulus Free - Formulas for Speaking Gullah, Sea Island Calculus! Formulus Free is the Creole or the Geechee dialect perfect study tool. It is a simple, Bonneville Salt Flats - South Pass easy to use, and easy to on the Oregon Trail navigate collection of the most Mouth of Arkansas River on important formulas and topics Arkansas-Mississippi border for high school and college Historic Route 66 students taking Calculus and Benjamin Bonneville led the first wagon train through Differential Equations. -

February 2016 Newsletter.Pdf

Newsletter, Volume V February, 2016 We hope you enjoy this issue of the BCHA Newsletter. Also check out our website www.bonnevilleheritage.org . TOUCH THE PAST AND ENGAGE THE FUTURE years. And, our third Achievement plaque to the Bonneville County Commissioners for their efforts in Welcome to you as members of the Bonneville County continuing to preserve the heritage and classical structure Heritage Association (BCHA). This newsletter is for you of our County Court House. as well as the many people we hope will join and become members of BCHA. As you enter for the program on March 4, you will be greeted with music by the Idaho Old Time Fiddlers. This Once again, it is time for Idaho Day. This annual Idaho outstanding group of musicians have provided music for Day celebration will happen because of legislation passed many of our programs. We will also have the Bonneville by Representative Linden Bateman establishing March 4 County Sheriff’s Office involved by doing the as Idaho Day with celebrations throughout Idaho. presentation of the colors with their color guard and the pledge of allegiance by Sheriff Paul Wilde. Idaho Day 2016 – Idaho Heroes program will be held Friday, March 4, at 7 pm in the Idaho Falls Civic One of our goals at BCHA is to get the youth involved. Auditorium. With the theme of Idaho Heroes, ten We do this in two ways. The first, is the outstanding individuals and businesses will be receiving plaques for student choir that Jennifer Korenke-Stanger organizes. the contributions they have provided in helping build She is the District #91 Elementary Music Specialist, and Bonneville County. -

An Historical Overview of Vancouver Barracks, 1846-1898, with Suggestions for Further Research

Part I, “Our Manifest Destiny Bids Fair for Fulfillment”: An Historical Overview of Vancouver Barracks, 1846-1898, with suggestions for further research Military men and women pose for a group photo at Vancouver Barracks, circa 1880s Photo courtesy of Clark County Museum written by Donna L. Sinclair Center for Columbia River History Funded by The National Park Service, Department of the Interior Final Copy, February 2004 This document is the first in a research partnership between the Center for Columbia River History (CCRH) and the National Park Service (NPS) at Fort Vancouver National Historic Site. The Park Service contracts with CCRH to encourage and support professional historical research, study, lectures and development in higher education programs related to the Fort Vancouver National Historic Site and the Vancouver National Historic Reserve (VNHR). CCRH is a consortium of the Washington State Historical Society, Portland State University, and Washington State University Vancouver. The mission of the Center for Columbia River History is to promote study of the history of the Columbia River Basin. Introduction For more than 150 years, Vancouver Barracks has been a site of strategic importance in the Pacific Northwest. Established in 1849, the post became a supply base for troops, goods, and services to the interior northwest and the western coast. Throughout the latter half of the nineteenth century soldiers from Vancouver were deployed to explore the northwest, build regional transportation and communication systems, respond to Indian-settler conflicts, and control civil and labor unrest. A thriving community developed nearby, deeply connected economically and socially with the military base. From its inception through WWII, Vancouver was a distinctly military place, an integral part of the city’s character. -

Newsletter of the Oregon-California Trails Association, Idaho Chapter Vol

Trail Dust Newsletter of the Oregon-California Trails Association, Idaho Chapter Vol. XXV Issue 3 Suzi Pengilly, Editor September 2013 Next Trail Dust will be released Dec. 15. Please send articles to Suzi Pengilly by Dec. 1. Calendar of Events October 5 Chapter Meetings—Kopper Kitchen, 2661 Airport Way, Boise 9:30 am Convention Planning Meeting 11:00 am Fall Chapter Meeting Thank You, Jim Payne With great sadness we share with you the August 9th passing of Idaho OCTA member Jim Payne. Upon returning from the national OCTA convention in late July, Jim saw a doctor for a pain in his side. It turned out to be pancreatic cancer-- and it was too late for any kind of effective treatment. A native Californian, Jim wore many hats throughout his life: husband, father, grandfather, aerospace engineer, vintner, 4-H leader, skier, “fast car” enthusiast, and lover of history. After the death of his wife, he moved to McCall, Idaho, in October 2002 with best friend and new life partner Pat Rhodes. Jim’s passion for history centered on the fur trade era and western emigration. He had been active in IOCTA for a number of years as a Director and had recently agreed to serve as co-chairman for the 2016 OCTA convention to be hosted by the Idaho chapter. Jim had recently been elected to the OCTA board of directors and started his term at the recent convention. Jim was a great asset to IOCTA— easy to work with and always willing to participate. Jim at the site of fur trade Fort Hall Please remember Pat as she deals with the sudden Contents loss of Jim. -

From Savage to Sublime (And Partway Back): Indians and Antiquity in Early Nineteenth-Century American Literature” Mark Niemeyer

“From Savage to Sublime (And Partway Back): Indians and Antiquity in Early Nineteenth-Century American Literature” Mark Niemeyer To cite this version: Mark Niemeyer. “From Savage to Sublime (And Partway Back): Indians and Antiquity in Early Nineteenth-Century American Literature”. Transatlantica. Revue d’études améri- caines/American Studies Journal, Association Française d’Études Américaines, 2016, 2015 (2), http://transatlantica.revues.org/7727. hal-01417834 HAL Id: hal-01417834 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01417834 Submitted on 2 Jun 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Transatlantica Revue d’études américaines. American Studies Journal 2 | 2015 The Poetics and Politics of Antiquity in the Long Nineteenth-Century / Exploiting Exploitation Cinema From Savage to Sublime (And Partway Back): Indians and Antiquity in Early Nineteenth-Century American Literature Mark Niemeyer Electronic version URL: https://journals.openedition.org/transatlantica/7727 DOI: 10.4000/transatlantica.7727 ISSN: 1765-2766 Publisher Association française d'Etudes Américaines (AFEA) Brought to you by Centre national de la recherche scientifique (CNRS) Electronic reference Mark Niemeyer, “From Savage to Sublime (And Partway Back): Indians and Antiquity in Early Nineteenth-Century American Literature”, Transatlantica [Online], 2 | 2015, Online since 01 June 2016, connection on 01 June 2021. -

United States Military Posts on the Mexico Border (1856 to Present)

Interpretive Themes and Related Resources 139 UNITED STATES MILITARY POSTS ON THE MEXICO BORDER (1856 TO PRESENT) Summary of Theme The operations and posts of the United States military are an important part of the history of the Santa Cruz Valley. The first United States Army post was established here in 1856, soon after the region was purchased from Mexico. The first duty was to protect mines and ranches from Apache attacks, which escalated just before troops were withdrawn at the beginning of the Civil War to be redeployed in the East. For a few months in 1862, the Confederate flag flew over the region, until Union troops arrived from California and recaptured it following the westernmost skirmishes of the Civil War. In 1865, United States troops were moved closer to the border to defend it against French troops that had invaded Mexico and occupied Sonora. Between 1866 and 1886, several new posts were established, and this region was the frontline of major campaigns to pacify the Apaches. A new post was established in Nogales in 1910, when the Mexican Revolution threatened to spill across the border. In 1916, this region was a staging area for the Punitive Expedition led by General John J. Pershing; it crossed into Mexico in pursuit of Pancho Villa after he attacked a town in southern New Mexico. Until the beginning of United States involvement in World War I, the military presence was swelled by National Guard units mobilized from western states to protect the border. From 1918 until 1933, the border was guarded by African-American cavalry and infantry regiments known as Buffalo Soldiers. -

Explorers of the Pacific Northwest: an Education Resource Guide

Explorersof thetheof PacificPacific NorthwNorthwestestest An Education Resource Guide Bureau of Land Management National Historic Oregon Trail Interpretive Center Baker City, Oregon This Education Resource guide was made possible through the cooperative efforts of: Bureau of Land Management Vale District National Historic Oregon Trail Interpretive Center Trail Tenders, Inc. Eastern Oregon University Northeast Oregon Heritage Fund of The Oregon Community Foundation J.G. Edwards Fund of The Oregon Community Foundation Content of this guide was developed by the Interpetive Staff at the National Historic Oregon Trail Interpretive Center, volunteers of Trail Tenders, Inc., and Eastern Oregon University students Michael Pace and Jim Dew. Artwork is by Tom Novak. Project co-ordination and layout by Sarah LeCompte. The Staff of the Interpretive Cen- ter and Trail Tenders would like to thank teachers from Baker City, Oregon 5J School District and North Powder, Oregon School District for their assistance in reviewing and test piloting materials in this guide. National Historic Oregon Trail Interpretive Center Explorers of the Pacific Northwest Introduction to Using This Guide This Education Resource Guide is designed for use by teachers and other educators who are teaching the history of the exploration of the Northwestern United States. Some activities are designed for the classroom while others are specific to the Interpretive Center and would necessitate a field trip to the site. This guide is designed for use by fourth grade teachers who traditionally teach Oregon history, but many activities can be adapted to younger or older students. This guide can be used to help meet benchmark one, benchmark two, and common curricu- lum goals in U.S. -

Explorers and Pioneers

Explorers and Pioneers Who was: Father Francisco Garces Seeking to open a land route between Tucson and California, Fray Francisco Garces explored the desert regions in 1775 and 1776. By the end of February 1776, he had reached the Mohave Villages located a few miles south of this location on the Arizona bank of the Colorado River. The Franciscan Father traveled alone in areas never before seen by a European American. Relying on Native American guides, he walked from village to village. The Mohaves agreed to lead him to the coast along a trail used for trade purposes. On March 4, 1776 accompanied by four natives, Garces crossed the Colorado River, reaching the San Gabriel Mission in California twenty days later. His route followed a much older prehistoric trail used to bring shells and other trade good to the tribes of the mountain and desert West. Garces Street in downtown Las Vegas is named after him. William S. “Old Bill” Williams "Old Bill" Williams (1787 - 1849) was a mountain man and frontiersman who served as an interpreter for the government, and led several expeditions in the West. Fluent in several languages, he lived with the Osage, where he married the daughter of a chief, and with the Ute. In late 1849, Williams joined Fremont’s doomed 4th Expedition, in which 10 men died trying to survey for a transcontinental railway line through the Sangre de Christo range (during winter). Williams left the group on a safer route but was killed by Ute Indians when he tried to return to find survivors. -

French in the History of Wyoming from La Salle to Arland

French in the History of Wyoming From La Salle to Arland Daniel A. Nichter https://wyo.press To Professor Emeritus Walter G. Langlois ii Preamble Let's address the elephant in the room: this is a book about history. And if that isn't boring enough, it's about Wyoming history, a state few people seem to know anything significant about. And to make it really boring, it's about French influences in the history of Wyoming. Wake up! This book is exciting and entertaining! Don't think of it as a history bookI don't. This is a book of stories, real and extraordinary people and their lives. Reality TV? Survivor series? Top chef? Amateurs, all of them! The people we're about meet will amaze and inspire you because, although their world was different, everything about them as humans is timeless. It doesn't matter that you and I have smart phones with GPS but they didn't even have hand-drawn maps of Wyoming. It doesn't matter that you and I have antibiotics but they just let a fever run its course, sometimes for a month or more. The facts of our worlds are radically different, but our hearts are the same: inspiration, determination, grit and perseverance; the joy of discovery, the loneliness of exploration; love, happiness, celebration; jealousy, anger, hatred; doubt, worry, and courage. This book is the product of years of research, undergirded by historical fact and the rigor of academic truth, but au cœur it is a book of stories as relevant today as one hundred years ago or one hundred years to come, for we are all explorers struggling to discover and settle new lands. -

Oigon Historic Tpms REPORT I

‘:. OIGoN HIsToRIc TPms REPORT I ii Presented by the Oregon Trails Coordinating Council May, 1998 h I Oregon Historic Trails Report Table of Contents . Executive summary 1 Project history 3 Introduction to Oregon’s Historic Trails 7 C Oregon’s National Historic Trails 11 C Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail 13 Oregon National Historic Trail 27 Applegate National Historic Trail 47 a Nez Perce National Historic Trail 63 C Oregon’s Historic Trails 75 Kiamath Trail, 19th Century 77 o Jedediah Smith Route, 1828 87 Nathaniel Wyeth Route, 1832/1834 99 C Benjamin Bonneville Route, 1833/1834 115 o Ewing Young Route, 1834/1837 129 Whitman Mission Route, 1841-1847 141 c Upper Columbia River Route, 1841-1851 167 John Fremont Route, 1843 183 o Meek Cutoff, 1845 199 o Cutoff to the Barlow Road, 1848-1884 217 Free Emigrant Road, 1853 225 o Santiam Wagon Road, 1865-1939 233 C General recommendations 241 Product development guidelines 243 Acknowledgements 247 4Xt C’ Executive summary C The Board of Directors and staff of the Oregon Trails Coordinating Council present the Oregon Historic Trails Report, the first step in the development of a statewide Oregon Historic C Trails Program. The Oregon Historic Trails Report is a general guide and planning document that will help future efforts to develop historic trail resources in Oregon. o The objective of the Oregon Historic Trails Program is to establish Oregon as the nation’s leader in developing historic trails for their educational, recreational, and economic values. The Oregon Historic Trails Program, when fully implemented, will help preserve and leverage C existing heritage resources while promoting rural economic development and growth through C heritage tourism. -

Inscribed Names in the Senate and House Chambers

Directory and Identification of Names Which Appear in Senate and House Chambers There are a total of 158 names: 69 in the Senate and 89 in the House. Senate Henry L. Abbot U.S. topographical engineer assigned to Pacific Railroad surveys. In 1855, he explored central Oregon for a railroad route to California. George Abernethy Methodist missionary who arrived in Oregon in 1840 as part of the Great Reinforcement for Jason Lee's mission. He became steward in charge of financial matters and later was one of the region's leading businessmen. Abernethy was elected governor of Provisional Government (1845-49). Martin d’ Aguilar Captain of the Tres Reyes, a Spanish sailing vessel, which voyaged the northwest coast in 1603. His ship's log contains one of the first written descriptions of the Oregon coast. John C. Ainsworth Foremost figure in the development of river transportation on the Willamette and Columbia Rivers. He was captain of the Lot Whitcomb and helped organize the Oregon Steam Navigation Company (1860), which established a virtual monopoly over Columbia River transportation that lasted for 20 years. George Atkinson Congregational missionary who arrived in Oregon in 1848, and was influential in the development of public education. Atkinson brought the first school books sold in the state and became the first school superintendent for Clackamas County. He founded the Clackamas Female Seminary in Oregon City, training the first teachers for Oregon schools. Atkinson helped found Tualatin Academy and wrote the education section of Governor Joseph Lane's inaugural address, which resulted in passage of the first school law, including a school tax. -

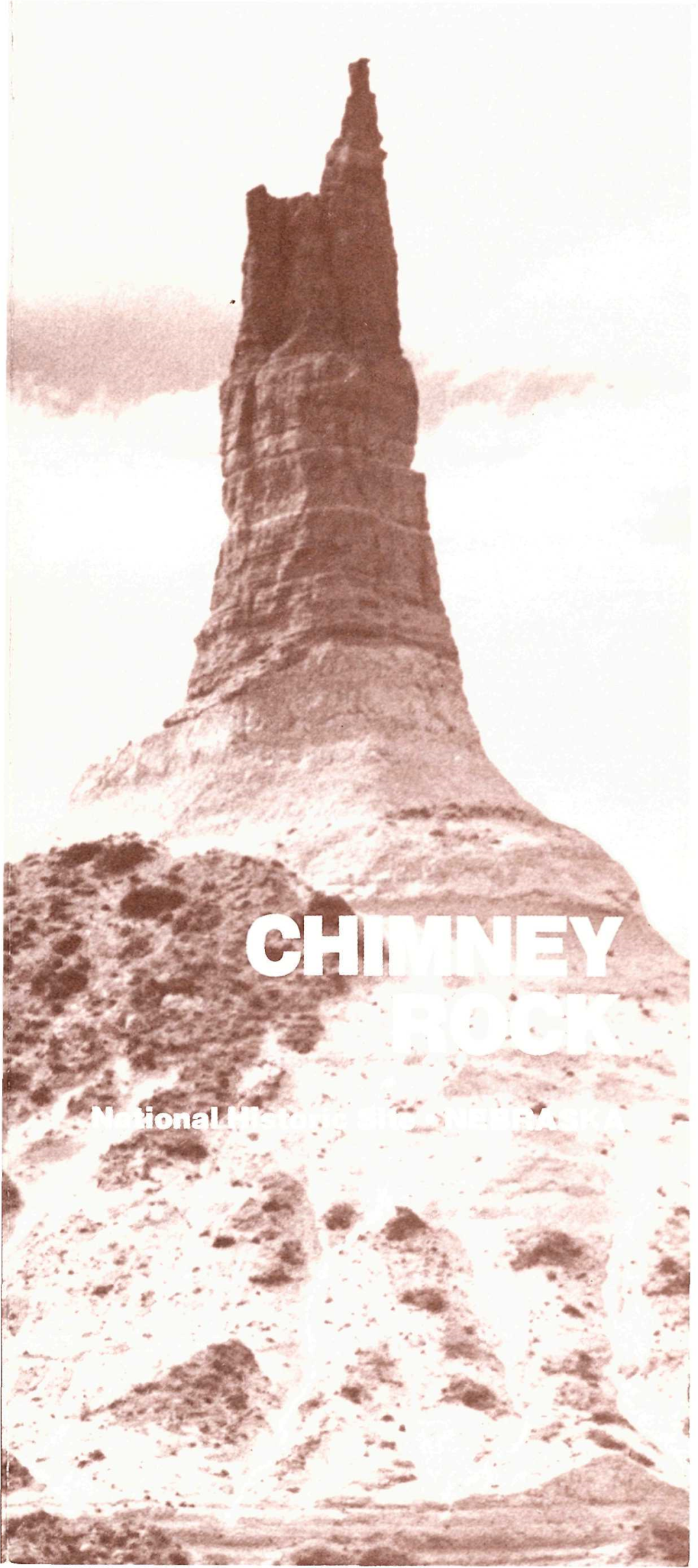

Chimney Rock Early Became a Guide

.a'- Ul^^|Llj2i2i himney Rock early became a guide for C "mountain men"—Rocky Mountain trappers CHIMNEY and traders—on their seasonal travels between the Rockies and the Missouri River trading marts. The first white men to see the column ROCK were probably Robert Stuart and his small National Historic Site group of traders on their way back from Astoria in the Oregon country in 1813. Fourteen years later, in 1827, the first recorded Hat this place was a singular use of the name occurred in Joshua Pilcher's phenomenon, which is among the report on his journey up the Platte Valley to curiosities of the country. It is called the Salt Lake rendezvous of the fur trappers. the Chimney. The lower part is a Among chroniclers of the landmark are names conical mound rising out of the naked famous in the annals of American expansion into the West: Captain Bonneville in 1832, plain; from the summit shoots up a William Anderson and William Sublette in 1834, shaft or column, about one hundred the Congregational missionary Samuel Parker and twenty feet in height, from which in 1835, the artist Alfred J. Miller in 1837, it derives its name. The height of the Father De Smet in 1840 and again in 1841, whole ... is a hundred and seventy Charles Preuss of Fremont's expedition in 1842, Courtesy, Walters Art Gallery © 1951, Univ. of Oklahoma Press five yards . and may be seen at the members of Gen. Stephen Kearny's dragoons in 1845, the historian Francis Parkman in 1846, and distance of upwards of thirty miles.Vt the pioneer photographer William H.