The Redland Estates of John Cossins, and What Happened to Them

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

4 Durdham Park BRISTOL • BS6 6XA 4 Durdham Park BRISTOL • BS6 6XA

4 Durdham Park BRISTOL • BS6 6XA 4 Durdham Park BRISTOL • BS6 6XA Immaculate family home with sunny gardens, garage and parking Bay fronted sitting room • Dining room Kitchen/Breakfast room • Master suite with dresser • 4/5 guest bedrooms • Family Bathroom • Guest Bathroom • Sun Terrace Gardens to front and rear • Double Garage • Off street parking Clifton 1.3 miles • Whiteladies Road 0.3 miles Park Street 1.5 miles • Bristol Temple Meads 3.0 miles Bristol International Airport 10.3 miles. (All distances are approximate) These particulars are intended only as a guide and must not be relied upon as statements of fact. Your attention is drawn to the Important Notice on the last page of the text. Situation The property is a short distance away from Redland Green School. Bristol provides a good selection of schools including Clifton College, Clifton High School, QEH, Bristol Grammar School, Badminton School for Girls and Redland Girls School. Other schools in the surrounding area include The Downs School at Wraxall. Nearby shops are in Henleaze (about 1.0 miles), Whiteladies Road (about 0.3 miles) and Clifton village (about 1.3 miles) which provide a variety of boutique shops, banks, restaurants, post offi ces, public houses and art galleries. The city centre is located approximately 1.9 miles away and provides extensive shopping facilities including Cabot Circus Shopping Centre, 2.1 miles and Cribbs Causeway is 4 miles. Access to the M4 is via the M32 motorway, as well as J18 of the M5. Bristol Temple Meads provides a fast train service to London Paddington which is approximately 90 minutes. -

Bristol Open Doors Day Guide 2017

BRING ON BRISTOL’S BIGGEST BOLDEST FREE FESTIVAL EXPLORE THE CITY 7-10 SEPTEMBER 2017 WWW.BRISTOLDOORSOPENDAY.ORG.UK PRODUCED BY WELCOME PLANNING YOUR VISIT Welcome to Bristol’s annual celebration of This year our expanded festival takes place over four days, across all areas of the city. architecture, history and culture. Explore fascinating Not everything is available every day but there are a wide variety of venues and activities buildings, join guided tours, listen to inspiring talks, to choose from, whether you want to spend a morning browsing or plan a weekend and enjoy a range of creative events and activities, expedition. Please take some time to read the brochure, note the various opening times, completely free of charge. review any safety restrictions, and check which venues require pre-booking. Bristol Doors Open Days is supported by Historic England and National Lottery players through the BOOKING TICKETS Heritage Lottery Fund. It is presented in association Many of our venues are available to drop in, but for some you will need to book in advance. with Heritage Open Days, England’s largest heritage To book free tickets for venues that require pre-booking please go to our website. We are festival, which attracts over 3 million visitors unable to take bookings by telephone or email. Help with accessing the internet is available nationwide. Since 2014 Bristol Doors Open Days has from your local library, Tourist Information Centre or the Architecture Centre during gallery been co-ordinated by the Architecture Centre, an opening hours. independent charitable organisation that inspires, Ticket link: www.bristoldoorsopenday.org.uk informs and involves people in shaping better buildings and places. -

Schedule 1 Updated Jan 22

SCHEDULE 1 Sites 1 – 226 below are those where nuisance behaviour that relates to the byelaws had been reported (2013). These are the original sites proposed to be covered by the byelaws in the earlier consultation 2013. 1 Albany Green Park, Lower Cheltenham Place, Ashley, Bristol 2 Allison Avenue Amenity Area, Allison Avenue, Brislington East, Bristol 3 Argyle Place Park, Argyle Place, Clifton, Bristol 4 Arnall Drive Open Space, Arnall Drive, Henbury, Bristol 5 Arnos Court Park, Bath Road, , Bristol 6 Ashley Street Park, Conduit Place, Ashley, Bristol 7 Ashton Court Estate, Clanage Road, , Bristol 8 Ashton Vale Playing Fields, Ashton Drive, Bedminster, Bristol 9 Avonmouth Park, Avonmouth Road, Avonmouth, Bristol 10 Badocks Wood, Doncaster Road, , Bristol 11 Barnard Park, Crow Lane, Henbury, Bristol 12 Barton Hill Road A/A, Barton Hill Road, Lawrence Hill, Bristol 13 Bedminster Common Open Space, Bishopsworth, Bristol 14 Begbrook Green Park, Frenchay Park Road, Frome Val e, Bristol 15 Blaise Castle Estate, Bristol 16 Bonnington Walk Playing Fields, Bonnington Walk, , Bristol 17 Bower Ashton Playing Field, Clanage Road, Southville, Bristol 18 Bradeston Grove & Sterncourt Road, Sterncourt Road, Frome Vale, Bristol 19 Brandon Hill Park, Charlotte Street, Cabot, Bristol 20 Bridgwater Road Amenity Area, Bridgwater Road, Bishopsworth, Bristol 21 Briery Leaze Road Open Space, Briery Leaze Road, Hengrove, Bristol 22 Bristol/Bath Cycle Path (Central), Barrow Road, Bristol 23 Bristol/Bath Cycle Path (East), New Station Way, , Bristol 24 Broadwalk -

Feuding Gentry and an Affray on College Green, Bristol, in 1579 by J

From the Transactions of the Bristol and Gloucestershire Archaeological Society Feuding Gentry and an Affray on College Green, Bristol, in 1579 by J. H. Bettey 2004, Vol. 122, 153-159 © The Society and the Author(s) Trans. Bristol & Gloucestershire Archaeological Society 122 (2004), 153–9 Feuding Gentry and an Affray on College Green, Bristol, in 1579 By JOSEPH BETTEY During the 1570s two wealthy, landed gentlemen engaged in a struggle for primacy in Bristol. They were Hugh Smyth, who possessed Ashton Court together with widespread estates in Somerset and south Gloucestershire, and John Young, owner of properties in Somerset, Wiltshire and Dorset. Their rivalry was to involve several other gentry families in the district, and culminated in a violent confrontation between their armed retainers on College Green in March 1579. The subsequent inquiry into the incident in the Court of Star Chamber provides much detail about the parties involved, as well as evidence about the status and use of College Green, and about the ancient chapel of St. Jordan and the open-air pulpit which stood on the Green. Although it was in existence for several centuries and was a focus of devotion in Bristol, little documentary evidence survives concerning St. Jordan and his chapel. The following account provides information about the chapel during the 16th century. Hugh Smyth’s wealth, his estates on the southern edge of Bristol, and his family connection with the city gave him a powerful claim to prominence. His father, John Smyth, had made a large fortune by trade through the port of Bristol and had invested his wealth in property in the city and the surrounding region, including the purchase of the Ashton Court estate in 1545. -

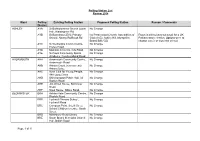

Polling Station List Review 2014

Polling Station List Review 2014 Ward Polling Existing Polling Station Proposed Polling Station Reason / Comments District ASHLEY AYA St Bartholomews Church Lower No Change Hall, Walsingham Rd AYB St Barnabas CEVC Primary Ivy Pentecostal Church, Assemblies of Room in school was too small for a UK School, Albany Rd/Brook Rd God (AoG), Ashley Hill, Montpelier, Parliamentary election. Options were to Bristol BS6 5JD change venue or close the school. AYC St Werburghs Comm Centre, No Change Horley Road AYD Malcolm X Centre, City Road No Change AYE St Pauls Community Sports No Change Academy, Newfoundland Road AVONMOUTH AHA Avonmouth Community Centre, No Change Avonmouth Road AHB Antona Court, (rear access) No Change Antona Drive. AHC Avon Club for Young People, No Change 98A Long Cross AHD Shirehampton Public Hall, 32 No Change Station Road AHE Jim O'Neil House, Kilminster No Change Road. AHF Stow House, Nibley Road. No Change BEDMINSTER BRA Ashton Vale Community Centre, No Change Risdale Road BRB Luckwell Primary School, No Change Luckwell Road BRC Compass Point, South Street No Change School Children’s centre, South Street BRD Marksbury Road Library No Change BRE South Bristol Methodist Church No Change Hall, British Road Page 1 of 11 Polling Station List Review 2014 Ward Polling Existing Polling Station Proposed Polling Station Reason / Comments District BISHOPSTON BSA Bishop Road Primary School No Change BSB St Michaels church Centre 160a No Change Gloucester Rd BSC Ashley Down Junior School, No Change Brunel Field BSD Ashley Down Junior -

Character Areas 4

Bristol Central Area Context Study Informing change Character areas 4 Bristol Central Area September 2013 Context Study - back to contents City Design Group 37 Character areas Criteria for character areas The character of each area refers to the predominant physical characteristics within each area. The The character areas have been defined using English boundaries are an attempt to define where these Heritage guidance provided in ‘Understanding Place: physical characteristics notably change, although there Historic Area Assessments: Principles and Practice’ will be design influences within neighbouring areas. (2010), although the boundaries have been adjusted to Therefore adjoining character should be considered in fit with existing Conservation Area or Neighbourhood any response to context. boundaries where practical. The key challenges and opportunities for each Detailed description of character areas has been character area are given at the end of each character provided where they intersect with the major areas of description section. These challenges are not an change as identified by the Bristol Central Area Plan. exhaustive list and are presented as the significant Summary pages have been provided for the remaining issues and potential opportunities as identified by the character areas including those within the Temple context study. Quarter Enterprise Zone (section 5). Further information about the Enterprise Zone is provided in the Temple Quarter Heritage Assessment and Temple Quarter Spatial Framework documents. Following the accepted guidelines each character area is defined by the aspects in 1.1 and primarily Topography, urban structure, scale and massing, building ages and material palette. This is in accordance with the emerging Development Management policies on local character and distinctiveness. -

A Co-Operative Academy

Cotham School A Co-operative Academy Newsletter - Term 1 October 2015 Inset Days: Wednesday 21 October 2015 Monday 2 November 2015 Cotham School, Cotham Lawn Road, Bristol, BS6 6DT T: 0117 919 8000 E: [email protected] W: www.cotham.bristol.sch.uk Letter from the Headteacher—October 2015 Dear Parents and Carers At the end of a very busy and successful term I would like to thank students for their hard work and excellent conduct as well as congratulating them on their achievements so far. I would also like to thank parents and carers for their con- tinued support. End of Term 1 Arrangements Wednesday 21 October is an INSET day so the last day of Term 1 for students is Tuesday 20 October. Start of Term 2 Arrangements Monday 2 November is an INSET day so the first day of Term 2 for students is Tuesday 3 November. Post 16 Open Evening The main North Bristol Post 16 Open Evening was held at Redland Green School from 6.30pm until 9.00pm. We will also be holding an Information Evening at Cotham Learning Community on 5 November from 7pm until 8pm. At our Information Evening, there will be some subject staff available. Year 11 Parents Evening Thank you to all Year 11 parents and carers who came to the very well- attended Year 11 Parents Evening on Monday 19 October. If you were not able to make the event but would still appreciate guidance on how to support your child with the next steps in their studies, please contact Mrs Wood (Learning Coordinator for Year 11) in the first instance. -

Ashton Park School

Ashton Park School Open Sessions Evening Thursday 22 September 2016, 6pm to 8.30pm (Headteacher’s talk 8pm) Headteacher Mr Nick John Day Monday 26 September 2016, 11.15am to 12.30pm Address Blackmoor’s Lane, Bower Ashton, Tuesday 27 September 2016, Bristol BS3 2JL 11.15am to 12.30pm t 0117 377 2777 f 0117 377 2778 e [email protected] www.ashtonpark.co.uk creates a genuine platform for every student to excel whether in Art, Drama, Music or Sport Status Foundation School to name but a few. Students are given many Age range 11–18 opportunities to travel abroad to further enrich Specialism Sports College their learning and achievements. Our links with a school in Kenya provides a particularly unique Our school is set in the beautiful surroundings and profound experience for which we have of Ashton Court Estate, providing a rich learning been awarded the prestigious International resource and outstanding location for our Schools Award. Our House System is designed students’ education. In February 2015 Ofsted to celebrate every student’s success and reward reported: The headteacher supported by leaders, them in a number of ways. We believe in listening governors, staff and students has acted with to and empowering students whilst seeking out determination to secure improvements in avenues of developing their leadership qualities. teaching and students’ achievement. The school’s We provide opportunities for them to take on capacity to improve further is strong. In April increasing responsibilities as they get older. We 2010 we became a Foundation School to allow us have developed a culture of excellence so as to create even closer links with our community students and staff we are constantly striving to to ensure our ethos and values reflect their needs improve together and contribute positively to our and desires. -

Situation of Polling Stations

SITUATION OF POLLING STATIONS Election of the Mayor for West of England Combined Authority Hours of Poll:- 7:00 am to 10:00 pm Notice is hereby given that: The situation of Polling Stations and the description of persons entitled to vote thereat are as follows: Ranges of electoral register Station Situation of Polling Station numbers of persons entitled Number to vote thereat St Bartholomew's Church - Upper Hall, Sommerville 1-WEST ASHA-1 to ASHA-1610 Road, Bristol Sefton Park Infant & Junior School, St Bartholomew's 2-WEST ASHB-1 to ASHB-1195 Road, Bristol St Bartholomew's Church - Upper Hall, Sommerville 3-WEST ASHC-1 to ASHC-1256 Road, Bristol Salvation Army Citadel, 6 Ashley Road, Bristol 4-WEST ASHD-1 to ASHD-1182/1 Ivy Pentecostal Church, Assemblies of God, Ashley 5-WEST ASHE-1 to ASHE-1216 Hill, Montpelier Ivy Pentecostal Church, Assemblies of God, Ashley 6-WEST ASHF-2 to ASHF-1440 Hill, Montpelier St Werburgh's Community Centre, Horley Road, St 7-WEST ASHG-1 to ASHG-1562 Werburghs Salvation Army Citadel, 6 Ashley Road, Bristol 8-WEST ASHH-1 to ASHH-1467 Malcolm X Community Centre, 141 City Road, St 9-WEST ASHJ-1 to ASHJ-1663 Pauls St Paul`s Community Sports Academy, Newfoundland 10- ASHK-1 to ASHK-966 Road, Bristol WEST St Paul`s Community Sports Academy, Newfoundland 11- ASHL-1 to ASHL-1067 Road, Bristol WEST Avonmouth Community Centre, Avonmouth Road, 12-NW AVLA-3 to AVLA-1688 Bristol Nova Primary School, Barracks Lane, Shirehampton 13-NW AVLB-1 to AVLB-1839 Hope Cafe and Church, 117 - 119 Long Cross, 14-NW AVLC-1 to AVLC-1673 -

List of Sites That Proposed Parks Byelaws Will Apply to (Appendix 2)

New parks byelaws site schedule 1 A Bond Open Space, Smeaton Road, Cabot, Bristol 2 Adelaide Place Park, Adelaide Place, Lawrence Hill, Bristol 3 Airport Road O/S, Airport Road, Bristol 4 Albany Green Park, Lower Cheltenham Place, Ashley, Bristol 5 Albion Road Amenity Area, Albion Road, Easton, Bristol 6 Allerton Crescent Amenity Area, Allerton Crescent, Hengrove, Bristol 7 Allison Avenue & Hill Lawn, Allison Road, Brislington East, Bristol 8 Allison Avenue Amenity Area, Allison Avenue, Brislington East, Bristol 9 Amercombe & Hencliffe Walk, Amercombe Walk, Stockwood, Bristol 10 Argyle Place Park, Argyle Place, Clifton, Bristol 11 Arnall Drive Open Space, Arnall Drive, Henbury, Bristol 12 Arnos Court Park, Bath Road, , Bristol 13 Ashley Street Park, Conduit Place, Ashley, Bristol 14 Ashton Court Estate, Clanage Road, , Bristol 15 Ashton Vale Playing Fields, Ashton Drive, Bedminster, Bristol 16 Avonmouth Park, Avonmouth Road, Avonmouth, Bristol 17 Badocks Wood, Doncaster Road, , Bristol 18 Bamfield Green Space, Bamfield, Hengrove, Bristol 19 Bangrove Walk CPG, Playford Gardens, Avonmouth, Bristol 20 Bannerman Road Park, Bannerman Road, Lawrence Hill, Bristol 21 Barnard Park, Crow Lane, Henbury, Bristol 22 Barton Hill Road A/A, Barton Hill Road, Lawrence Hill, Bristol 23 Bath Road 3 Lamps PGSS, Bath Road, Windmill Hill, Bristol 24 Bedminster Common Open Space, Bishopsworth, Bristol 25 Begbrook Green Park, Frenchay Park Road, Frome Vale, Bristol 26 Bellevue Road Park, Belle Vue Road, Easton, Bristol 27 Belmont Street Amenity Area, Belmont -

The Rise of a Gentry Family: the Smyth's of Ashton Court, C. 1500

BRISTOL BRANCH OF THE HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION LOCAL HISTORY PAMPHLETS THE RISE OF A GENTRY FAMILY STILL IN PRINT 3. The Theatre Royal: first seventy years. Kathleen Barker. 20p 8. The Steamship Great Western by Grahame Farr. 30p 13. The Port of Bristol in the Middle Ages by J. W. Sherborne. 25p THE SMYTHS OF ASHTON COURT 15. The Bristol Madrigal Society by Herbert Byard. 15p 16. Ei�hteenth Century Views of Bristol by Peter Marcy. 15p 18. The Industrial Archaeology of Bristol by R. A. Buchanan. J Sp 23. Prehistoric Bristol by L. V. Grinsell. 20p I 25. John Whitson and the Merchant Community of Bristol by Patrick McGrath. 20p 26. Nineteenth Century Engineers in the Port of Bristol by R. A. Buchanan. 20p c. 1500 1642 21. Bristol Shipbur'ldingin the Nineteenth Century by Grahame Farr. 25p 28. Bristol in the Middle Ages by David Walker. 25p 29. Bristol Corporation of the Poor 1699-1898 by E. E. Butcher. 25p 30. The Bristol Mint by L. V. Grinsell. 30p 31. The Marian Martyrs by K. G. Powell. 30p 32. Bristol Trades Council 1873-1973 by David Large and Robert Whitfield. 30p 33. Entertainment in the Nineties by Kathleen Barker. 30p 34. The Bristol Riots by Susan Thomas. 35p 35. Public Health in mid-Victorian Bristol by David Large and Frances Round. 35p by H. BETTEY 36. The Establishment of the Bristol Police Force by R. Walters. J. 40p 37. Bristol and the Abolition of Slavery by Peter Marshall. 40p 38. 1747-1789 by Jonathan Press. I The Merchant Seamen of Bristol 50p 39. -

Spring 2013 Bristolcivicsociety.Org.Uk

ETTER RISTOL B The Bristol Civic Society magazine B Issue 02 Spring 2013 bristolcivicsociety.org.uk including Annual Review and AGM details An independent force for a better Bristol Contents Join us 2 FEATURES Bristol Civic Society 4 Cumberland Piazza – Ray Smith - an independent force for a better Bristol 5 Temple Meads transport hub – Dave Cave - is a registered charity. 8 Ready, willing and able? – Christopher Brown 9 Unbuilt Bristol – Eugene Byrne A large part of our income, 10 Know your heritage at risk – Pete Insole which comes from membership subscriptions, 12 Local List – Bob Jones is spent on producing this magazine. 13 New Hope for Old Market – Leighton Deburca If you are not already a BCS member and would like 14 Census and Sensibility – Eugene Byrne to support us and have Better Bristol magazine 16 Saving Ashton Court Mansion – Peter Weeks delivered to your address, please consider joining us. 17 Bristol’s listed gardens - Ros Delany 18 The Architecture Centre - Christine Davies Individual membership for the first year is £10 if you set up a standing order and £20 annually thereafter. BRISTOL CIVIC SOCIETY ANNUAL REVIEW Contact Maureen Pitman, Membership Secertary 19 Chair’s Statement • [email protected] & AGM Invitation - Heather Leeson 0117 974 3637 20 Public Spaces Group 2012 Reviews - Alan Morris bristolcivicsociety.org.uk/ 21 Historical Group membership/membership form 2012 Review - Alan Morris 21 Heritage Group - Mariateresa Bucciante 22 Planning Application Group 2012 Review - John Payne 22 Notes