State Finance in the Great Depression

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Job Creation Programs of the Great Depression: the WPA and the CCC Name Redacted Specialist in Labor Economics

Job Creation Programs of the Great Depression: The WPA and the CCC name redacted Specialist in Labor Economics January 14, 2010 Congressional Research Service 7-.... www.crs.gov R41017 CRS Report for Congress Prepared for Members and Committees of Congress Job Creation Programs of the Great Depression: the WPA and the CCC ith the exception of the Great Depression, the recession that began in December 2007 is the nation’s most severe according to various labor market indicators. The W 7.1 million jobs cut from employer payrolls between December 2007 and September 2009, when it is thought the latest recession might have ended, is more than has been recorded for any postwar recession. Job loss was greater in a relative sense during the latest recession as well, recording a 5.1% decrease over the period.1 In addition, long-term unemployment (defined as the proportion of workers without jobs for longer than 26 weeks) was higher in September 2009—at 36%—than at any time since 1948.2 As a result, momentum has been building among some members of the public policy community to augment the job creation and worker assistance measures included in the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (P.L. 111-5). In an effort to accelerate improvement in the unemployment rate and job growth during the recovery period from the latest recession,3 some policymakers recently have turned their attention to programs that temporarily created jobs for workers unemployed during the nation’s worst economic downturn—the Great Depression—with which the latest recession has been compared.4 This report first describes the social policy environment in which the 1930s job creation programs were developed and examines the reasons for their shortcomings then and as models for current- day countercyclical employment measures. -

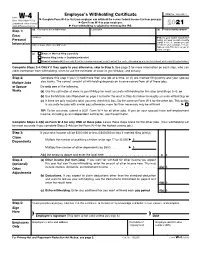

Form W-4, Employee's Withholding Certificate

Employee’s Withholding Certificate OMB No. 1545-0074 Form W-4 ▶ (Rev. December 2020) Complete Form W-4 so that your employer can withhold the correct federal income tax from your pay. ▶ Department of the Treasury Give Form W-4 to your employer. 2021 Internal Revenue Service ▶ Your withholding is subject to review by the IRS. Step 1: (a) First name and middle initial Last name (b) Social security number Enter Address ▶ Does your name match the Personal name on your social security card? If not, to ensure you get Information City or town, state, and ZIP code credit for your earnings, contact SSA at 800-772-1213 or go to www.ssa.gov. (c) Single or Married filing separately Married filing jointly or Qualifying widow(er) Head of household (Check only if you’re unmarried and pay more than half the costs of keeping up a home for yourself and a qualifying individual.) Complete Steps 2–4 ONLY if they apply to you; otherwise, skip to Step 5. See page 2 for more information on each step, who can claim exemption from withholding, when to use the estimator at www.irs.gov/W4App, and privacy. Step 2: Complete this step if you (1) hold more than one job at a time, or (2) are married filing jointly and your spouse Multiple Jobs also works. The correct amount of withholding depends on income earned from all of these jobs. or Spouse Do only one of the following. Works (a) Use the estimator at www.irs.gov/W4App for most accurate withholding for this step (and Steps 3–4); or (b) Use the Multiple Jobs Worksheet on page 3 and enter the result in Step 4(c) below for roughly accurate withholding; or (c) If there are only two jobs total, you may check this box. -

PERSONAL INCOME TAX LAW (Updated Text*)

PERSONAL INCOME TAX LAW (updated text*) PART ONE GENERAL PROVISIONS Article 1 This Law introduces the personal income tax and regulates the taxation procedure of the civilian's personal income. Article 2 Personal income tax (hereinafter: income tax) is paid annually for the sum of the net revenue from all sources, except for the revenues that are tax exempt by this Law. Article 3 The following types of revenues earned in the country and abroad are included in the income according to which the tax base is determined: 1) personal income from employment, pensions and disability pensions; 2) income from agriculture; 3) personal income from financial and professional activities; 4) income from property and property rights; 5) other types of revenues. All revenues under paragraph 1 of this article which are paid in cash, paid in kind or through other means, are subject to taxation. Article 4 For the different types of revenues under article 3 of this Law, an advance payment of the income tax is calculated throughout the fiscal year, which is paid by deduction from each salary payment or based on the decision of the public revenue authorities, unless otherwise determined by this Law. The amount of the compensated tax under paragraph 1 of this article is deducted from the estimated annual income tax, while the tax reductions are accepted in the amount approved with the advance estimation. _________________________________ *)The Law is published in the " Official Gazette of Republic of Macedonia",No.80/93, and the amendment and supplement in 70/94,71/96 and 28/97 Article 5 The annual amount of the income tax and the amounts of the advance payments and tax reductions that are deducted from the annual taxation are determined by the regulations that are valid on January 1 in the taxable year, unless otherwise determined by this Law. -

Chapter 2: What's Fair About Taxes?

Hoover Classics : Flat Tax hcflat ch2 Mp_35 rev0 page 35 2. What’s Fair about Taxes? economists and politicians of all persuasions agree on three points. One, the federal income tax is not sim- ple. Two, the federal income tax is too costly. Three, the federal income tax is not fair. However, economists and politicians do not agree on a fourth point: What does fair mean when it comes to taxes? This disagree- ment explains, in large measure, why it so difficult to find a replacement for the federal income tax that meets the other goals of simplicity and low cost. In recent years, the issue of fairness has come to overwhelm the other two standards used to evaluate tax systems: cost (efficiency) and simplicity. Recall the 1992 presidential campaign. Candidate Bill Clinton preached that those who “benefited unfairly” in the 1980s [the Tax Reform Act of 1986 reduced the top tax rate on upper-income taxpayers from 50 percent to 28 percent] should pay their “fair share” in the 1990s. What did he mean by such terms as “benefited unfairly” and should pay their “fair share?” Were the 1985 tax rates fair before they were reduced in 1986? Were the Carter 1980 tax rates even fairer before they were reduced by President Reagan in 1981? Were the Eisenhower tax rates fairer still before President Kennedy initiated their reduction? Were the original rates in the first 1913 federal income tax unfair? Were the high rates that prevailed during World Wars I and II fair? Were Andrew Mellon’s tax Hoover Classics : Flat Tax hcflat ch2 Mp_36 rev0 page 36 36 The Flat Tax rate cuts unfair? Are the higher tax rates President Clin- ton signed into law in 1993 the hallmark of a fair tax system, or do rates have to rise to the Carter or Eisen- hower levels to be fair? No aspect of federal income tax policy has been more controversial, or caused more misery, than alle- gations that some individuals and income groups don’t pay their fair share. -

Chapter 24 the Great Depression

Chapter 24 The Great Depression 1929-1933 Section 1: Prosperity Shattered • Recount why financial experts issued warnings about business practices during the 1920s. • Describe why the stock market crashed in 1929. • Understand how the banking crisis and subsequent business failures signaled the beginning of the Great Depression. • Analyze the main causes of the Great Depression. Objective 1: Recount why financial experts issued warnings about business practices during the 1920s. • Identify the warnings that financial experts issued during the 1920s: • 1 Agricultural crisis • 2 Sick industry • 3 Consumers buying on credit • 4 Stock speculation • 5 Deion is # 1 Objective 1: Recount why financial experts issued warnings about business practices during the 1920s. • Why did the public ignore these warnings: • 1 Economy was booming • 2 People believed it would continue to grow Objective 2: Describe why the stock market crashed in 1929. Factors That Caused the Stock Market Crash 1. Rising interest rates 2. Investors sell stocks 3. Stock prices plunge 4. Heavy sells continue The Crash Objective 3: Understand how the banking crisis and subsequent business failures signaled the beginning of the Great Depression. Depositor withdrawal Banking Crisis Default on loans The Banking Crisis Margin calls and Subsequent Business Failures Unable to obtain resources Business Failures Lay-offs and closings Objective 4: Analyze the main causes of the Great Depression. • Main causes of the Great Depression and how it contributed to the depression: • Global economic crises, the U.S didn’t have foreign consumers. • The income gap deprived businesses of national consumers • The consumers debt led to economic chaos Section 2: Hard Times • Describe how unemployment during the Great Depression affected the lives of American workers. -

Employment, Personal Income and Gross Domestic Product)

South Dakota e-Labor Bulletin February 2013 February 2013 Labor Market Information Center SD Department of Labor & Regulation How is South Dakota faring in BEA Economic Indicators? (Employment, Personal Income and Gross Domestic Product) From the January 2013 South Dakota e-Labor Bulletin Employment Data from BEA The U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) publishes employment data for state and local areas. The data includes an estimate of the total number of jobs, including both full- and part-time jobs and detailed by place of work. (Full- and part-time jobs are counted at equal weight.) Employees, sole proprietors and active partners are all included, but unpaid family workers and volunteers are not. Proprietors are those workers who own and operate their own businesses and are reported as either farm or nonfarm workers. The number of workers covered by unemployment insurance is a key component of the employment data published by the BEA and in information compiled by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS). For more information regarding covered workers, see the South Dakota Covered Workers & Annual Pay 2011 Annual Summary on our website at www.sdjobs.org/lmic/menu_covered_workers2011.aspx. The chart on the following page shows annual employment change during the 2000-2011 period. Comparative data is included for the United States, South Dakota and the Plains Region (Iowa, Kansas, Missouri, Nebraska, North Dakota and South Dakota). (continued on next page) Page 1 of 23 South Dakota e-Labor Bulletin February 2013 For the 2010-2011 period, which reflects economic recovery, South Dakota attained a total employment growth rate of 1.2 percent, compared to a growth rate of 1.1 percent for the Plains Region and 1.3 percent for the nation. -

Iowa Personal Income and Wage/Salary Income

IOWA PERSONAL INCOME AND WAGE/SALARY INCOME Overview. Personal income includes wage and salary income and income earned through the operation of farms and other businesses, rent, interest, dividends, and government transfer income (Social Security, unemployment insurance, etc.). Iowa Wage and Salary Growth. Wage and salary income is a component of overall personal income. Over time, Iowa wage and salary income equals about 50.0% of total personal income. Wage and salary income is not as volatile as overall personal income. Since the end of the December 2007 U.S. recession in June 2009, annual Iowa wage and salary income growth has averaged about 3.2%. For the second quarter of calendar year (CY) 2021, wage and salary income increased 1.5% compared to the first quarter of CY 2021 and increased 11.2% compared to the same quarter of CY 2020. Iowa Personal Income Growth. Iowa personal income increased 1.3% for the second quarter of CY 2021 when compared to the same quarter of CY 2020. Income decreased 6.1% from the first quarter of CY 2021, due to a reduction in economic stimulus from the federal government. Personal income growth for the second quarter of CY 2020 was revised up to 11.9% from the originally released growth rate. Personal income growth is quite volatile over time, as is evident in Chart 2. In addition to quarterly volatility, reported personal income for Iowa suffers from significant revisions, usually related to changes in estimated farm income. Farm Proprietor Income. Since 2012, Iowa overall personal income has been growing more slowly than Iowa wage and salary income due to the decline in Iowa farm proprietor income. -

Measuring the Great Depression

Lesson 1 | Measuring the Great Depression Lesson Description In this lesson, students learn about data used to measure an economy’s health—inflation/deflation measured by the Consumer Price Index (CPI), output measured by Gross Domestic Product (GDP) and unemployment measured by the unemployment rate. Students analyze graphs of these data, which provide snapshots of the economy during the Great Depression. These graphs help students develop an understanding of the condition of the economy, which is critical to understanding the Great Depression. Concepts Consumer Price Index Deflation Depression Inflation Nominal Gross Domestic Product Real Gross Domestic Product Unemployment rate Objectives Students will: n Define inflation and deflation, and explain the economic effects of each. n Define Consumer Price Index (CPI). n Define Gross Domestic Product (GDP). n Explain the difference between Nominal Gross Domestic Product and Real Gross Domestic Product. n Interpret and analyze graphs and charts that depict economic data during the Great Depression. Content Standards National Standards for History Era 8, Grades 9-12: n Standard 1: The causes of the Great Depression and how it affected American society. n Standard 1A: The causes of the crash of 1929 and the Great Depression. National Standards in Economics n Standard 18: A nation’s overall levels of income, employment and prices are determined by the interaction of spending and production decisions made by all households, firms, government agencies and others in the economy. • Benchmark 1, Grade 8: Gross Domestic Product (GDP) is a basic measure of a nation’s economic output and income. It is the total market value, measured in dollars, of all final goods and services produced in the economy in a year. -

Self-Employment Guide a Resource for SNAP and Cash Programs

Economic Assistance and Employment Supports Division Self-Employment Guide A resource for SNAP and Cash Programs Self-Employment Guide Table of Contents Table of Contents ............................................................................................................ 2 SE 01.0 Introduction ........................................................................................................ 3 SE 02.0 Definition of a self-employed person ................................................................. 3 SE 03.0 Self-employment ownership types ..................................................................... 3 SE 03.1 Sole Proprietorship ........................................................................................ 3 SE 03.2 Partnership ..................................................................................................... 4 SE 03.3 S Corporations ............................................................................................... 5 SE 03.4 Limited Liability Company (LLC) .................................................................... 6 SE 04.0 Method of Calculation ........................................................................................ 7 SE 05.0 Verifications ....................................................................................................... 7 SE 06.0 Self-employment certification steps ................................................................. 10 SE 07.0 Self-employment Net Income Calculation – 50% Method ............................... -

Chapter 1: Meet the Federal Income

Hoover Classics : Flat Tax hcflat ch1 Mp_1 rev0 page 1 1. Meet the Federal Income Tax The tax code has become near incomprehensible except to specialists. Daniel Patrick Moynihan, Chairman, Senate Finance Committee, August 11, 1994 I would repeal the entire Internal Revenue Code and start over. Shirley Peterson, Former Commissioner, Internal Revenue Service, August 3, 1994 Tax laws are so complex that mechanical rules have caused some lawyers to lose sight of the fact that their stock-in-trade as lawyers should be sound judgment, not an ability to recall an obscure paragraph and manipulate its language to derive unintended tax benefits. Margaret Milner Richardson, Commissioner, Internal Revenue Service, August 10, 1994 It will be of little avail to the people, that the laws are made by men of their own choice, if the laws be so voluminous that they cannot be read, or so incoherent that they cannot be understood; if they be repealed or revised before they are promulgated, or undergo such incessant changes that no man, who knows what the law is to-day, can guess what it will be to-morrow. Alexander Hamilton or James Madison, The Federalist, no. 62 the federal income tax is a complete mess. It’s not efficient. It’s not fair. It’s not simple. It’s not compre- hensible. It fosters tax avoidance and cheating. It costs billions of dollars to administer. It costs taxpayers bil- lions of dollars in time spent filling out tax forms and Hoover Classics : Flat Tax hcflat ch1 Mp_2 rev0 page 2 2 The Flat Tax other forms of compliance. -

Ohio Income Tax Update: Changes in How Unemployment Benefits Are Taxed for Tax Year 2020

Ohio Income Tax Update: Changes in how Unemployment Benefits are taxed for Tax Year 2020 On March 31, 2021, Governor DeWine signed into law Sub. S.B. 18, which incorporates recent federal tax changes into Ohio law effective immediately. Specifically, federal tax changes related to unemployment benefits in the federal American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) of 2021 will impact some individuals who have already filed or will soon be filing their 2020 Ohio IT 1040 and SD 100 returns (due by May 17, 2021). Ohio taxes unemployment benefits to the extent they are included in federal adjusted gross income (AGI). Due to the ARPA, the IRS is allowing certain taxpayers to deduct up to $10,200 in unemployment benefits. Certain married taxpayers who both received unemployment benefits can each deduct up to $10,200. This deduction is factored into the calculation of a taxpayer’s federal AGI, which is the starting point for Ohio’s income tax computation. Some taxpayers will file their 2020 federal and Ohio income tax returns after the enactment of the unemployment benefits deduction, and thus will receive the benefit of the deduction on their original returns. However, many taxpayers filed their federal and Ohio income tax returns and reported their unemployment benefits prior to the enactment of this deduction. As such, the Department offers the following guidance related to the unemployment benefits deduction for tax year 2020: • Taxpayers who do not qualify for the federal unemployment benefits deduction. o Ohio does not have its own deduction for unemployment benefits. Thus, if taxpayers do not qualify for the federal deduction, then all unemployment benefits included in federal AGI are taxable to Ohio. -

Inflation Expectations and the Recovery from the Great Depression in Germany

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Daniel, Volker; ter Steege, Lucas Working Paper Inflation Expectations and the Recovery from the Great Depression in Germany Working Papers of the Priority Programme 1859 "Experience and Expectation. Historical Foundations of Economic Behaviour", No. 6 Provided in Cooperation with: German Research Foundation's Priority Programme 1859 "Experience and Expectation. Historical Foundations of Economic Behaviour", Humboldt-Universität Berlin Suggested Citation: Daniel, Volker; ter Steege, Lucas (2018) : Inflation Expectations and the Recovery from the Great Depression in Germany, Working Papers of the Priority Programme 1859 "Experience and Expectation. Historical Foundations of Economic Behaviour", No. 6, Humboldt University Berlin, Berlin, http://dx.doi.org/10.18452/19198 This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/223187 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte.