Living with Changing Climate Impact, Vulnerability and Adaptation Challenges in Indian Sundarbans

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dwelling in Loss Environment, Displacement and Memory in the Indian Ganges Delta

Dwelling in Loss Environment, Displacement and Memory in the Indian Ganges Delta Arne Harms Dwelling in Loss: Environment, Displacement and Memory in the Indian Ganges Delta Inauguraldissertation zur Erlangung des Grades eines Dr. phil. Vorgelegt am Fachbereich Politik- und Sozialwissenschaften der Freien Universität Berlin von Arne Harms, M.A. Berlin, Dezember 2013 Erstgutachterin: Prof. Dr. Ute Luig Zweitgutachterin: Prof. Dr. Shalini Randeria Tag der Disputation: 10. Juli 2014 Memories are crafted by oblivion as the outlines of the shore are created by the sea. Marc Augé, Oblivion Contents Acknowledgements ................................................................................................................... iv Table of Figures ........................................................................................................................ vi A Note on Transliteration ......................................................................................................... vii Glossary ................................................................................................................................... viii 1. Introduction ......................................................................................................................... 1 1.1. Methodology ........................................................................................................................... 7 1.2. Structure of the Thesis .......................................................................................................... -

Household Survey of Pesticide Practice, Deliberate Self-Harm, and Suicide in the Sundarban Region of West Bengal, India

Household Survey of Pesticide Practice, Deliberate Self-Harm, and Suicide in the Sundarban Region of West Bengal, India The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Banerjee, Sohini, Arabinda Narayan Chowdhury, Esther Schelling, and Mitchell G. Weiss. 2013. “Household Survey of Pesticide Practice, Deliberate Self-Harm, and Suicide in the Sundarban Region of West Bengal, India.” BioMed Research International 2013: 1–9. doi:10.1155/2013/949076. Published Version doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2013/949076 Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:23016711 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Hindawi Publishing Corporation BioMed Research International Volume 2013, Article ID 949076, 9 pages http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2013/949076 Research Article Household Survey of Pesticide Practice, Deliberate Self-Harm, and Suicide in the Sundarban Region of West Bengal, India Sohini Banerjee,1,2 Arabinda Narayan Chowdhury,3 Esther Schelling,2,4 and Mitchell G. Weiss2,4 1 Institute of Psychiatry, 7 D.L. Khan Road, Kolkata 700 025, India 2 Department of Epidemiology & Public Health, Swiss Tropical & Public Health Institute, Basel, Switzerland 3 Stuart Road Resource Centre, Northamptonshire Healthcare NHS Foundation Trust, Corby, Northants NN17 1RJ, UK 4 University of Basel, Basel, Switzerland Correspondence should be addressed to Sohini Banerjee; [email protected] Received 27 April 2013; Revised 26 July 2013; Accepted 30 July 2013 Academic Editor: Niranjan Saggurti Copyright © 2013 Sohini Banerjee et al. -

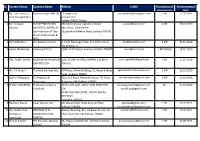

Mr. Sudhin Kumar

Sl. Contact Person Company Name Address E-Mail Description of Announcement Requirement Date 1 Mr. Sarojit Hazra/ West Bengal Webel Bhavan, Block EP&GP, Sector-V, Salt [email protected] 2 MT 17.07.2019 Mr. Sudhin Kumar Electronics Industry Lake, Bidhannagar, Kolkata: 700 091 Development Corporation Limited 2 CS Komal Jain Keonjhar Infrastructure 68/5C Ballygunge Place, Kolkata - 700019 [email protected]/kidco.komal@g 1 MT 16.07.2019 Development Company mail.com Limited 3 CS SHIKHA BAJAJ HINDUSTHAN UDYOG Trinity Plaza, 3rd Floor, 84/1A, Topsia [email protected] 2 MT 09.07.2019 LIMITED Road(South), Kolkata-700046 4 Ms. Kavita Balmer Lawrie & Co. 21, Netaji Subhas Road, Kolkata-700001 [email protected] 3 MT 29.06.2019 Bhavsar(CS) Ltd. 5 Neelam Arora SKSRN & ASSOCIATES 40, WESTON STREET , 2ND FLOOR ,ROOM [email protected] 2 MT 19.06.2019 NO. 20, KOLKATA-700013 6 Mr. Mahesh Shah Inter Corporate 1/1 Monica Building 9B, Lord Sinha Road, [email protected] 4 MT 15.06.2019 Financiers & Kolkata-700071, Near Shri Shikshayatan Consultants Ltd. College 7 Suyash Nahata East India Securities DA-14 Saltlake City, Sector-1 [email protected] 2 - 3 MT 14.06.2019 Limited Kolkata-700064 8 Priti Agarwal Precision Weldarc 46C Chowringhee Road, Everest House, Flat [email protected] 2 MT 14.06.2019 Limited 14G, 14th Floor, Kolkata-700071 9 Ms. Jyoti Purohit TM INTERNATIONAL TM International Logistics Limited [email protected] 1 MT 28.05.2019 LOGISTICS LIMITED (A 14th Floor, Tata Centre Joint Venture of Tata 43,Jawaharlal Nehru Road, Kolkata-700071 Steel/ IQ Martrade & NYK) 10 Mr. -

Adaptive Measures for Suistanable Condition in Sunderban by Various Institutions

Journal of Xi’an Shiyou University, Natural Science Edition ISSN : 1673-064X ADAPTIVE MEASURES FOR SUISTANABLE CONDITION IN SUNDERBAN BY VARIOUS INSTITUTIONS Anupma Kumari Shailendra Kumar Singh Dept.of Zoology,Magadh University, Dept.of Zoology,Magadh University Bodhgaya,Bihar Bodhgaya,Bihar ABSTRACT Sunderban forest is shared between Bangladesh and India, it is the world’s largest, continuous coastal wetland. It covers an area of about one million hectares in the delta of the rivers Ganges, Brahmaputra, and Meghna. Enormous amounts of sediments carried by the river system contribute to the expansion and dynamics of this delta. The Sunderban area experiences subtropical monsoonal climate with an annual rainfall of 1,600–1,800 mm and occasional severe cyclonic storms [2]. The maximum elevation within the Sundarbans is only 10 m above the mean sea level. The western and eastern limits of the Sundarbans are defined by the course of the River Hooghly (a distributary of river Ganges) and River Baleshwar, respectively. About 60 % of the mangrove forests lie in the Khulna District of Bangladesh and the rest in the 24-Paragnas District of West Bengal (India). A large number of channels and creeks flow into larger rivers in the Sundarbans. The Sundarbans, shared between Bangladesh and India, is the world’s largest, continuous coastal wetland. It covers an area of about one million hectares in the delta of the rivers Ganges, Brahmaputra, and Meghna. Enormous amounts of sediments carried by the river system contribute to the expansion and dynamics of this delta. The Sundarbans area experiences subtropical monsoonal climate with an annual rainfall of 1600–1800 mm and occasional severe cyclonic storms [2]. -

Annual Report 2018-19 80Th Year Contents

Accelerating focussed growth Integrated Annual Report 2018-19 80th Year Contents Integrated Report Deep innovation expertise to harness the 01-57 best of science and serve the society. 01 Company Overview A passion to consistently push beyond 06 Our Diversified Science Led Portfolio 08 Performance Highlights for FY 2018-19 existing limits and rise above. 10 Board of Directors Combine innovation and passion with scale 12 Management Team and accelerated growth happens. 13 MD & CEO's Message 14 Integrated Value Chain This is how Tata Chemicals has emerged to be one of the world’s most reputed brands, revolutionising the 16 Business Model Explaining the Interlinkage of Capitals industry segments it has operated in its 18 Our Formula for Accelerating 80-year journey. Focussed Growth As we continue to nurture our inherent strengths, 21 Managing Risks, Maximising Returns we are undertaking many initiatives to accelerate our 24 Listening to and Engaging growth in focussed areas. with the Stakeholders 25 Addressing Material Issues Our multi-pronged strategy of customer-centric 26 Basic Chemistry Business product development and expansion into white spaces in our Consumer Products Business and capacity 32 Consumer Products Business augmentation programmes in our Specialty Products 38 Specialty Chemicals Business Business has laid a strong foundation for growth. 45 Intensifying Focus on Health & Safety Aligning our organisational structure and strategies 46 Innovating for a Better World with the revised segment reporting and the exit from 48 Growing Together non-core businesses has simplified our portfolio and are 50 Our Commitment to driving stronger synergies. Strong innovation drive is Sustainable Growth enabling us to tap the emerging areas and 53 Corporate Social Responsibility nurture the newly-seeded portfolio. -

Sl. Contact Person Company Name Address E-Mail Description of Requirement Announcement Date 2 Mr. Ashwani Jaiswal TM INTERNATION

Sl. Contact Person Company Name Address E-Mail Description of Announcement Requirement Date 1 Mr. S.M. Varma, CS Supreme Paper Mills Ltd 12,Darga Road [email protected] 2 MT 17.10.2019 Cum Manager(A&F) Ground Floor Kolkata-700017.( India) 2 Mr. Ashwani TM INTERNATIONAL TM International Logistics Limited [email protected] 2 MT 16.10.2019 Jaiswal LOGISTICS LIMITED (A 14th Floor, Tata Centre Joint Venture of Tata 43,Jawaharlal Nehru Road, Kolkata-700071 Steel/ IQ Martrade & NYK) 3 Mr M Bhuteria A C Bhuteria and Co 2, India Exchange Place, 2nd Floor, Room [email protected] 3 MT 16.10.2019 10, Kolkata - 1 4 Sayan Mukherjee Sanmarg Pvt Ltd 160B, Chittaranjan Avenue, Kolkata-700007 [email protected] 2 MT (Male) 16.10.2019 5 MR. SUMIT SAHAL MURLIDHAR RATANLAL 15B, HEMANTA BASU SARANI, KOLKATA [email protected] 1 MT 15.10.2019 EXPORTS LTD 700 001 6 Mr. P K Ghosh Transafe Services Ltd. 6th Floor, Annex Building, 21, Netaji Subhas [email protected] 1 MT 15.10.2019 Road, Kolkata-700001 7 Sachin Chhaparia E Chhaparia & 33/1, N.S Road, Marshall House, 7th Floor, [email protected] 1 MT 15.10.2019 Associates Room no.748, Kolkata-700001 8 SHRISTI AGARWAL Practising Company 90 PHEARS LANE 2ND FLOOR ROOM NO [email protected]; MT 15.10.2019 Secretary 205 [email protected] NEAR POODAR COURT, BESIDE SHILPA BHAWAN KOLKATA -700012 9 Roshaan Davve Terai Tea Co. Ltd. 10, Government Place East 1st Floor, [email protected], 1 MT 03.10.2019 Kolkata-700069 [email protected] 10 Ms. -

Library Catalogue

Id Access No Title Author Category Publisher Year 1 9277 Jawaharlal Nehru. An autobiography J. Nehru Autobiography, Nehru Indraprastha Press 1988 historical, Indian history, reference, Indian 2 587 India from Curzon to Nehru and after Durga Das Rupa & Co. 1977 independence historical, Indian history, reference, Indian 3 605 India from Curzon to Nehru and after Durga Das Rupa & Co. 1977 independence 4 3633 Jawaharlal Nehru. Rebel and Stateman B. R. Nanda Biography, Nehru, Historical Oxford University Press 1995 5 4420 Jawaharlal Nehru. A Communicator and Democratic Leader A. K. Damodaran Biography, Nehru, Historical Radiant Publlishers 1997 Indira Gandhi, 6 711 The Spirit of India. Vol 2 Biography, Nehru, Historical, Gandhi Asia Publishing House 1975 Abhinandan Granth Ministry of Information and 8 454 Builders of Modern India. Gopal Krishna Gokhale T.R. Deogirikar Biography 1964 Broadcasting Ministry of Information and 9 455 Builders of Modern India. Rajendra Prasad Kali Kinkar Data Biography, Prasad 1970 Broadcasting Ministry of Information and 10 456 Builders of Modern India. P.S.Sivaswami Aiyer K. Chandrasekharan Biography, Sivaswami, Aiyer 1969 Broadcasting Ministry of Information and 11 950 Speeches of Presidente V.V. Giri. Vol 2 V.V. Giri poitical, Biography, V.V. Giri, speeches 1977 Broadcasting Ministry of Information and 12 951 Speeches of President Rajendra Prasad Vol. 1 Rajendra Prasad Political, Biography, Rajendra Prasad 1973 Broadcasting Eminent Parliamentarians Monograph Series. 01 - Dr. Ram Manohar 13 2671 Biography, Manohar Lohia Lok Sabha 1990 Lohia Eminent Parliamentarians Monograph Series. 02 - Dr. Lanka 14 2672 Biography, Lanka Sunbdaram Lok Sabha 1990 Sunbdaram Eminent Parliamentarians Monograph Series. 04 - Pandit Nilakantha 15 2674 Biography, Nilakantha Lok Sabha 1990 Das Eminent Parliamentarians Monograph Series. -

Cyclonic Storm Landfalls in Bangladesh, West Bengal and Odisha, 1877–2016

WPS8316 Policy Research Working Paper 8316 Public Disclosure Authorized Cyclonic Storm Landfalls in Bangladesh, West Bengal and Odisha, 1877–2016 Public Disclosure Authorized A Spatiotemporal Analysis Sunando Bandyopadhyay Susmita Dasgupta Zahirul Huque Khan David Wheeler Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Development Research Group Environment and Energy Team & Environment and Natural Resources Global Practice Group January 2018 Policy Research Working Paper 8316 Abstract Recurrent cyclonic storms in the Bay of Bengal inflict mas- shifted eastward, there is a marked variability in location, sive losses on the coastal regions of Bangladesh and India. especially after 1960. Impacts also have varied considerably Information on occurrences and severities of cyclones is within and across zones over time, with the highest-im- necessary for understanding household and community pact zones in northern Odisha and the Sundarbans region responses to cyclone risks. This paper constructs a georef- of West Bengal. The pronounced spatial and temporal erenced panel database that can be used to obtain such variation in cyclone impacts will provide robust controls information for Bangladesh, West Bengal, and Odisha. for comparative research on household and community Cyclone strike locations and impact zones are analyzed adaptation to cyclones in the study region. The meth- for several historical periods between 1877 and 2016. The odology developed in the paper is general and could be findings indicate that although the median location has expanded to an arbitrarily large set of coastal locations. This paper is a product of the Environment and Energy Team, Development Research Group and the Environment and Natural Resources Global Practice Group. It is part of a larger effort by the World Bank to provide open access to its research and make a contribution to development policy discussions around the world. -

TISS Ph.D Information Broacher.Pdf

Tata Institute of Social Sciences Information Brochure For M.Phil and Ph.D Programs 2012-2013 TATA INSTITUTE OF SOCIAL SCIENCES (A Deemed University, established under Section 3 of the UGC Act, 1965) V.N.Purav Marg, Deonar, Mumbai – 400 088 Phone : 25525000, Fax:91 22 25525050 http://www.tiss.edu 1 Tata Institute of Social Sciences Contents: 1. About Tata Institute of Social Sciences 2. Schools and Independent Centres 3. Research Focus Of Schools And Independent Centres 4. About M.Phil and PhD program at TISS 5. Admission • Admission Eligibility • Admission Procedure 6. Reservation 7. Admission of International Students To Programmes 8. Fees and deposits 9. Student Services • Library • Hostel Accommodation and Dining Hall • SC/ST Cell • Committee against Sexual Harassment • Free Counselling • Free Medical Consultation 10. Frequently Asked Questions 2 Tata Institute of Social Sciences 1. About Tata Institute of Social Sciences The Tata Institute of Social Sciences (TISS) was established in 1936, as the Sir Dorabji Tata Graduate School of Social Work. In 1944, the Sir Dorabji Tata Graduate School of Social Work was renamed as the Tata Institute of Social Sciences. The year 1964 was an important landmark in the history of the Institute, when it was declared deemed to be a university under section 3 University Grants Commission Act, 1956. Since its inception in 1936, the vision of the TISS has been to be an institution of excellence in higher education that continually responds to changing social realities through the development and application of knowledge, towards creating a people-centered ecologically sustainable and just society that promotes and protects dignity, equality, social justice and human rights for all. -

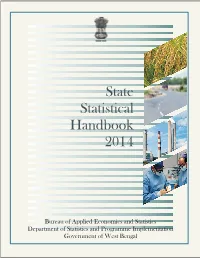

State Statistical Handbook 2014

STATISTICAL HANDBOOK WEST BENGAL 2014 Bureau of Applied Economics & Statistics Department of Statistics & Programme Implementation Government of West Bengal PREFACE Statistical Handbook, West Bengal provides information on salient features of various socio-economic aspects of the State. The data furnished in its previous issue have been updated to the extent possible so that continuity in the time-series data can be maintained. I would like to thank various State & Central Govt. Departments and organizations for active co-operation received from their end in timely supply of required information. The officers and staff of the Reference Technical Section of the Bureau also deserve my thanks for their sincere effort in bringing out this publication. It is hoped that this issue would be useful to planners, policy makers and researchers. Suggestions for improvements of this publication are most welcome. Tapas Kr. Debnath Joint Administrative Building, Director Salt Lake, Kolkata. Bureau of Applied Economics & Statistics 30th December, 2015 Government of West Bengal CONTENTS Table No. Page I. Area and Population 1.0 Administrative Units in West Bengal - 2014 1 1.1 Villages, Towns and Households in West Bengal, Census 2011 2 1.2 Districtwise Population by Sex in West Bengal, Census 2011 3 1.3 Density of Population, Sex Ratio and Percentage Share of Urban Population in West Bengal by District 4 1.4 Population, Literacy rate by Sex and Density, Decennial Growth rate in West Bengal by District (Census 2011) 6 1.5 Number of Workers and Non-workers -

Study of Bob Cyclone Aila: Moisture Effects on Heavy Rain and Flooding in Bangladesh, Bhutan, Ne-India and Nepal

STUDY OF BOB CYCLONE AILA: MOISTURE EFFECTS ON HEAVY RAIN AND FLOODING IN BANGLADESH, BHUTAN, NE-INDIA AND NEPAL Sk. Md. Abubakar Abdullah* and Mohan Kumar Das SAARC Meteorological Research Centre (SMRC), Agargaon, Dhaka 1207, Bangladesh *E-mail of corresponding author: [email protected] ABSTRACT Cyclone AILA-2009 was of moderate intensity that ravaged southwestern part of Bangladesh badly. Alongside, it ravaged West Bengal of India, eastern Nepal and southern Bhutan. Due to torrential rain these four countries experienced flooding effects. A series of heavy rainfall events caused devastating floods across portions of south central and southwest Bangladesh into Northwestern Bangladesh, Southeastern Nepal and Bhutan from May 26-27, 2009. The occurrence of both a frontal and mesoscale convection pattern and the entrainment of tropical moisture from western Bay of Bengal (BoB) combined to produce heavy rainfall. The wet spell episode persisted over a two days period. An extensive area with storm totals of 25 to 50 mm stretched from southwest Bangladesh into southeastern Nepal and Bhutan. This is a case study examining the meso-scale, upper air and hydro-logic aspects which led to the prolonged heavy rain and flood episode. Advanced Research WRF (ARW) Model with horizontal resolution of 9 km x 9 km, 50s time step and 27 vertical levels has been used to simulate the nature of Cyclone AILA and its associated wind, rainfall etc. Six hourly Final Reanalysis (FNL) data of National Centers for Environmental Prediction (NCEP) were used as input to WRF-ARW Model for the simulation of “AILA”. The model results are compared with the TRMM, Kalpana-1 images and the India Meteorological Department (IMD) predicted results. -

Condition of Agricultural Productivity of Gosaba C.D. Block, South24 Parganas, West Bengal, India After Severe Cyclone Aila

International Journal of Scientific and Research Publications, Volume 3, Issue 7, July 2013 1 ISSN 2250-3153 Condition of Agricultural Productivity of Gosaba C.D. Block, South24 Parganas, West Bengal, India after Severe Cyclone Aila Ajay Debnath* * Department of Geography, University of Calcutta Abstract- On 25th May 2009 morning severe cyclone Aila hit the Hodges, marks the northern limit of the Sundarbans, running in a Bay of Bengal coast of The Indian Sundarban region with it tidal slightly zigzag pattern from Basirhat in the north-east to Kulpi surges of up to 6.5 metres, affecting 11 coastal districts. This along the Hugli in the west. Politically the Sundarbans in North- surge of water damaged and washed away over 1,743kms of 24 Parganas falls within the six Blocks of Minakhan, Haroa, embankments, removing the only protection available to many Sandeshkhali-I and II, Hasnabad and Hingalganj while in South people along the coast. This tidal surge causes floods over the 24 Parganas it extends over thirteen Blocks of Gosaba, Basanti, entire region which brought high salinity and pH. This flood Canning-I, Canning-II, Joynagar-I, Joynagar-II, Kultuli, increased salinity and pH condition of agricultural land and Patharpratima, Namkhana, Sagar, Kakdwip and Mathurapur-II. highly affect over crop production. Crop production has The entire Indian Sundarban covers an area of 9630 sq. km markedly reduced after this severe cyclone. Economic conditions bounded between estuary of river Hugli in the East, Bay of of the people in this region also highly affected by this natural Bengal in the South, Ichhamati-Raimangal in the East and disaster.