Exploring Indus Crop Processing: Combining Phytolith and Macrobotanical Analyses to Consider the Organisation of Agriculture in Northwest India C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Archaeozoological Methods

Indian Journal of Archaeology Faunal Remains from Sampolia Khera (Masudpur I), Haryana P.P. Joglekar1, Ravindra N. Singh2 and C.A. Petrie3 1-Department of Archaeology,Deccan College (Deemed University), Pune 411006,[email protected] 2-Department of A.I.H.C. and Archaeology, Banaras Hindu University, Varanasi 221005, [email protected] 3-Department of Archaeology, University of Cambridge, Downing Street, Cambridge CB2 3DZ, UK, [email protected] Introduction The site of Masudpur I (Sampolia Khera) (29° 14.636’ N; 75° 59.611’) (Fig. 1), located at a distance of about 12 km from the large urban site of Rakhigarhi, was excavated under the Land, Water and Settlement project of the Dept. of Archaeology of Banaras Hindu University and University of Cambridge in 2009. The site revealed presence of Early, Mature and Late Harappan cultural material1. Faunal material collected during the excavation was examined and this is final report of the material from Masudpur I (Sampolia Khera). Fig. 1: Location of Sampolia Khera (Masudpur I) 25 | P a g e Visit us: www.ijarch.org Faunal Remains from Sampolia Khera (Masudpur I), Haryana Material and Methods Identification work was done at Banaras Hindu University in 2010. Only a few fragments were taken to the Archaeozoology Laboratory at Deccan College for confirmation. After the analysis was over select bones were photographed and all the studied material was restored back to the respective cloth storage bags. Since during excavation archaeological material was stored with a context number, these context numbers were used as faunal analytical units. Thus, in the tables the original data are presented under various cultural units, labelled as phases by the excavators (Table 1). -

Curriculum Vitae

Curriculum Vitae Of Dr. R.S. Bisht Joint Director General (Retd.) Archaeological Survey of India & Padma Shri Awardee, 2013 Address: 9/19, Sector-3, Rajendranagar, Sahibabad, Ghaziabad – 201005 (U.P.) Tel: 0120-3260196; Mob: 09990076074 Email: [email protected] i Contents Pages 1. Personal Data 1-2 2. Excavations & Research 3-4 3. Conservation of Monuments 5 4. Museum Activities 6-7 5. Teaching & Training 8 6. Research Publications 9-12 7. A Few Important Research papers presented 13-14 at Seminars and Conferences 8. Prestigious Lectures and Addresses 15-19 9. Memorial Lectures 20 10. Foreign Countries and Places Visited 21-22 11. Members on Academic and other Committees 23-24 12. Setting up of the Sarasvati Heritage Project 25 13. Awards received 26-28 ii CURRICULUM VITAE 1. Personal Data Name : DR. RAVINDRA SINGH BISHT Father's Name : Lt. Shri L. S. Bisht Date of Birth : 2nd January 1944 Nationality : Indian by birth Permanent Address : 9/19, Sector-3, Rajendranagar, Sahibabad Ghaziabad – 201 005 (U.P.) Academic Qualifications Degree Subject University/ Institution Year M.A . Ancient Indian History and Lucknow University, 1965. Culture, PGDA , Prehistory, Protohistory, School of Archaeology 1967 Historical archaeology, Conservation (Archl. Survey of India) of Monuments, Chemical cleaning & preservation, Museum methods, Antiquarian laws, Survey, Photography & Drawing Ph. D. Emerging Perspectives of Kumaun University 2002. the Harappan Civilization in the Light of Recent Excavations at Banawali and Dholavira Visharad Hindi Litt., Sanskrit, : Hindi Sahitya Sammelan, Prayag 1958 Sahityaratna, Hindi Litt. -do- 1960 1 Professional Experience 35 years’ experience in Archaeological Research, Conservation & Environmental Development of National Monuments and Administration, etc. -

VLE List Hisar District

VLE List Hisar District Block CSC LOCATION VLE_NAME Status Adampur Kishangarh Anil Kumar Working Adampur Khairampur Bajrang Bali Working Adampur Mandi Adampur Devender Duddi not working Adampur Chaudhariwali Vishnu Kumar Working Adampur Bagla Parhlad Singh Working Adampur Chuli Bagrian Durgesh Working Adampur Adampur Gaon Manmohan Singh Working Adampur Sadalpur Mahender Singh Working Adampur Khara Barwala Vinod Kumar Working Adampur Moda Khera Jitender Working Adampur Kabrel Suresh Rao Working Adampur Chuli Kallan Pushpa Rani Working Adampur Ladvi Anil Kumar Working Adampur Chuli Khurd Mahesh Kumar Working Adampur Daroli Bharat Singh Working Adampur Chabarwal Sandeep Kumar Working Adampur Dhani Siswal Sunil Kumar Working Adampur Jawahar Nagar Rachna not working Adampur Asrawan Ramesh Kumar Working Adampur Mahlsara Parmod Kumar Working Adampur Dhani Mohbatpur Sandeep Kumar Working ADAMPUR Mohbatpur Parmod Working ADAMPUR Kajla Ravinder Singh not working Adampur Mothsara Pawan Kumar Working Adampur Siswal Sunil Kumar Working Adampur Gurshal Surender Singh not working Adampur Kohli Indra Devi Working Adampur Telanwali Nawal Kishore Working Agroha Fransi Bhupender Singh Working Agroha Kuleri Hanuman Working Agroha Agroha Suresh Kumar not working Agroha Nangthala Mohit Kathuria Working Agroha Kanoh Govind Singh Working Agroha Kirori Vinod Kumar Working Agroha Shamsukh Pawan Kumar Working Agroha Chikanwas Kuldeep Kumar Working Agroha Siwani Bolan Sanjay Kumar Working Agroha Mirpur Sandeep Kumar Working Agroha Sabarwas Sunil kumar Working Agroha -

Banawali an Indus Site in Haryana

Banawali An Indus Site in Haryana https://www.harappa.com/blog/banawali-indus-site-haryana Search our site home blog Banawali An Indus Site in Haryana slideshows September 25th, 2016 essays articles books videos resources about us Username * Password * Create new account Request new password Log in "The centralized planning of the Harappan settlements," writes the archaeologist write Dilip Chakrabarti, "is one of their most famous features. Although they were not laid strictly on chessboard patterns with invariably straight roads, they do show many signs of careful planning. Places like Mohenjodaro, Harappa, and Kalibangan had low, large eastern 1 of 2 9/29/16, 12:14 AM Banawali An Indus Site in Haryana https://www.harappa.com/blog/banawali-indus-site-haryana sectors and separately walled, higher but smaller western sectors. There is clear evidence that the buildings of western sectors were laid out on a high artificial mud platform (80,000 square metres and 7 metres high in the case of Mohenjodaro), fortified with bastions and towers. The eastern sector too lay within a wall but the scale of fortification here was less impressive. "The practice of putting a wall around a settlement dates to the Early Harappan period but its division into two separately enclosed sectors appears to coincide with the Mature Harappan stage. Because the western sector is raised higher than the eastern one and it is enclosed, archaeologists suggest that it may have been reserved for public buildings, the performance of ceremonies, and the residences of the elites. The rest may have dwelt in the eastern sector which had closely built burnt-brick or mud-brick houses lining streets which are often more than ten metres wide and lanes which are less than two metres wide. -

On the Brink: Water Governance in the Yamuna River Basin in Haryana By

Water Governance in the Yamuna River Basin in Haryana August 2010 For copies and further information, please contact: PEACE Institute Charitable Trust 178-F, Pocket – 4, Mayur Vihar, Phase I, Delhi – 110 091, India Society for Promotion of Wastelands Development PEACE Institute Charitable Trust P : 91-11-22719005; E : [email protected]; W: www.peaceinst.org Published by PEACE Institute Charitable Trust 178-F, Pocket – 4, Mayur Vihar – I, Delhi – 110 091, INDIA Telefax: 91-11-22719005 Email: [email protected] Web: www.peaceinst.org First Edition, August 2010 © PEACE Institute Charitable Trust Funded by Society for Promotion of Wastelands Development (SPWD) under a Sir Dorabji Tata Trust supported Water Governance Project 14-A, Vishnu Digambar Marg, New Delhi – 110 002, INDIA Phone: 91-11-23236440 Email: [email protected] Web: www.watergovernanceindia.org Designed & Printed by: Kriti Communications Disclaimer PEACE Institute Charitable Trust and Society for Promotion of Wastelands Development (SPWD) cannot be held responsible for errors or consequences arising from the use of information contained in this report. All rights reserved. Information contained in this report may be used freely with due acknowledgement. When I am, U r fine. When I am not, U panic ! When I get frail and sick, U care not ? (I – water) – Manoj Misra This publication is a joint effort of: Amita Bhaduri, Bhim, Hardeep Singh, Manoj Misra, Pushp Jain, Prem Prakash Bhardwaj & All participants at the workshop on ‘Water Governance in Yamuna Basin’ held at Panipat (Haryana) on 26 July 2010 On the Brink... Water Governance in the Yamuna River Basin in Haryana i Acknowledgement The roots of this study lie in our research and advocacy work for the river Yamuna under a civil society campaign called ‘Yamuna Jiye Abhiyaan’ which has been an ongoing process for the last three and a half years. -

Abrcs (Aug-2021)

List of Vacancies Offered in Re-Counselling of ABRCs (Aug-2021) SN District BlockName Cluster Name 1 Ambala AMBALA-I (CITY) GSSS MAJRI 2 Ambala AMBALA-I (CITY) GSSS MOHRI BHANOKHERI 3 Ambala AMBALA-I (CITY) GSSS CHHAPRA 4 Ambala AMBALA-I (CITY) GSSS JANSUI 5 Ambala AMBALA-I (CITY) GSSS ISMAILPUR 6 Ambala AMBALA-I (CITY) GSSS NAGGAL 7 Ambala AMBALA-I (CITY) GSSS NANYOLA 8 Ambala AMBALA-I (CITY) GSSS BAKNOUR 9 Ambala AMBALA-I (CITY) GSSS DURANA 10 Ambala AMBALA-I (CITY) GSSS SHAHPUR 11 Ambala AMBALA-II (CANTT.) GSSS GHEL 12 Ambala AMBALA-II (CANTT.) GSSS RAMBAGH ROAD,A/CANTT 13 Ambala AMBALA-II (CANTT.) GSSS BOH 14 Ambala AMBALA-II (CANTT.) GSSS GARNALA 15 Ambala AMBALA-II (CANTT.) GSSS RAMPUR SARSHERI 16 Ambala AMBALA-II (CANTT.) GSSS SULTANPUR 17 Ambala AMBALA-II (CANTT.) GSSS PANJOKHRA 18 Ambala BARARA GSSS DHANAURA 19 Ambala BARARA GSSS DHEEN 20 Ambala BARARA GSSS TANDWAL 21 Ambala BARARA GSSS UGALA 22 Ambala BARARA GSSS MULLANA 23 Ambala BARARA GSSS THAMBER 24 Ambala BARARA GSSS HOLI 25 Ambala BARARA GSSS ZAFFARPUR 26 Ambala BARARA GSSS RAJOKHERI 27 Ambala BARARA GSSS MANKA-MANKI 28 Ambala NARAINGARH GSSS NAGLA RAJPUTANA 29 Ambala NARAINGARH GSSS KATHEMAJRA 30 Ambala NARAINGARH GSSS DERA 31 Ambala NARAINGARH GSSS BHUREWALA 32 Ambala NARAINGARH GSSS JEOLI 33 Ambala NARAINGARH GSSS LAHA 34 Ambala NARAINGARH GSSS BHARERI KALAN 35 Ambala NARAINGARH GSSS SHAHPUR NURHAD 36 Ambala NARAINGARH GSSS KANJALA 37 Ambala NARAINGARH GSSS GADHAULI 38 Ambala SAHA GSSS KESRI 39 Ambala SAHA GSSS SAMLEHRI 40 Ambala SAHA GSSS NAHONI List of Vacancies Offered -

Haryana Chapter Kurukshetra

Panchkula Yamunanagar INTACH Ambala Haryana Chapter Kurukshetra Kaithal Karnal Sirsa Fatehabad Jind Panipat Hisar Sonipat Rohtak Bhiwani Jhajjar Gurgaon Mahendragarh Rewari Palwal Mewat Faridabad 4 Message from Chairman, INTACH 08 Ambala Maj. Gen. L.K. Gupta AVSM (Retd.) 10 Faridabad-Palwal 5 Message from Chairperson, INTACH Haryana Chapter 11 Gurgaon Mrs. Komal Anand 13 Kurukshetra 7 Message from State Convener, INTACH Haryana Chapter 15 Mahendragarh Dr. Shikha Jain 17 Rohtak 18 Rewari 19 Sonipat 21 Yamunanagar 22 Military Heritage of Haryana by Dr. Jagdish Parshad and Col. Atul Dev SPECIAL SECTION ON ARCHAEOLOGY AND RAKHIGARHI 26 Urban Harappans in Haryana: With special reference to Bhiwani, Hisar, Jhajjar, Jind, Karnal and Sirsa by Apurva Sinha 28 Rakhigarhi: Architectural Memory by Tapasya Samal and Piyush Das 33 Call for an International Museum & Research Center for Harrapan Civilization, at Rakhigarhi by Surbhi Gupta Tanga (Director, RASIKA: Art & Design) MESSAGE FROM THE CHAIRMAN INTACH Over 31 years from its inception, INTACH has been dedicated towards conservation of heritage, which has reflected in its various works in the field of documentation of tangible and intangible assets. It has also played a crucial role in generating awareness about the cultural heritage of the country, along with heritage awareness programmes for children, professionals and INTACH members. The success of INTACH is dedicated to its volunteers, conveners and members who have provided valuable inputs and worked in coordination with each other. INTACH has been successful in generating awareness among the local people by working closely with the local authorities, local community and also involving the youth. There has been active participation by people, with addition of new members every year. -

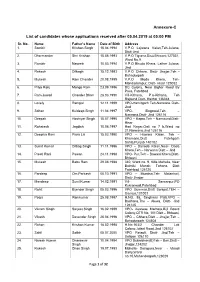

Annexure-C List of Candidates Whose Applications Received After 05.04

Annexure-C List of candidates whose applications received after 05.04.2019 at 05:00 PM Sr. No. Name Father’s Name Date of Birth Address 1. Sombir Krishan Singh 15.04.1994 V.P.O Lajwana Kalan,Teh-Julana, Distt-Jind 2. Dharmender Shri Krishan 15.08.1993 V.P.O Tigrana,Distt Bhiwani,127031, Ward No.9 3. Rambir Naseeb 10.03.1994 V.P.O Bhuda Khera, Lather Julana, Jind 4. Rakesh Dilbagh 15.12.1993 V.P.O Chhara, Distt- Jhajjar,Teh - Bahadurgarh 5. Mukesh Ram Chander 20.08.1995 V.P.O Moda Khera, Teh- Mandadampur, Distt- Hisar 125052 6. Priya Ranj Mange Ram 23.09.1996 DC Colony, Near Bighar Road By Pass, Fatehbad 7. Ram Juwari Chander Bhan 28.03.1990 Vill-Kithana, P.o-Kithana, Teh Rajaund,Distt- Kaithal 136044 8. Lovely Rampal 12.11.1999 VPO-Hamirgarh Teh-Narwana Distt- Jind 9. Sohan Kuldeep Singh 11.04.1997 VPO- Singowal,Teh – Narwana,Distt- Jind 126116 10. Deepak Hoshiyar Singh 15.07.1995 VPO – Kapro,Teh – Narnaund,Distt- Hisar 11. Rohatash Jagdish 10.06.1997 Hari Nagar,Gali no 7 b,Ward no 21,Narwana,Jind 126116 12. Deepika Rani Piara Lal 15.03.1990 VPO – Hawara Kalan, Teh – Khamano,Distt Fatehgarh Sahib,Punjab 140102 13. Sumit Kumar Dilbag Singh 11.11.1996 VPO – Danoda Kalan,Near- Dada Khera,Teh – Narwana Distt – Jind 14. Preeti Rani Pawan 24.11.1998 VPO- Pur,Teh – Bawani Khera,Distt- Bhiwani 15. Mukesh Babu Ram 29.08.1988 340, Ward no. 9, Killa Mohalla, Near Balmiki Mandir, Tohana, Distt Fatehbad 125120 16. -

Curriculum and Syllabus Outlines

Four Year Integrated Programme in Teacher Education Leading to the degree of B.A. /B.Sc./B.Com. B.Ed. CURRICULUM AND SYLLABUS OUTLINES Maharshi Dayanand University Rohtak Maharshi Dayanand University Rohtak Syllabus Outlines (Educational Studies and Practicum) st 1 Semester ES 1.1 Human Development during Childhood and Adolescence Time: 3 Hours Maximum marks: 100 (External: 80, Internal: 20) Note for Paper Setters: i) Paper setters will set 9 questions in all, out of which students will be required to attempt 5 questions. ii) Q. No. 1 will be compulsory and carries 16 marks. It will be com- prised of 4 short- answer type notes of 4 marks each to be selected from the entire syllabus. iii) Two long-answer type questions will be set from each of the four units, out of which the students will be required to attempt one ques- tion from each unit. Long-answer type questions will carry 16 marks each. iv) All questions will carry equal marks. Objectives of the Course This Course aims at developing an understanding of the constructs of childhood and adolescence from a socio-cultural perspective. Several issues pertaining to development are raised and addressed, so as to encourage students to look at and appreciate pluralistic per- spectives. The student-teacher is also to be equipped with a clear un- derstanding of special needs and issues of inclusion. Social, econom- ic and cultural differences in socialization are looked at critically, so as to enable the students to gain insights into factors influencing children. An attempt has been made to integrate the implications for each aspect of development with the unit itself. -

Architectural Features of the Early Harappan Forts

Ancient Punjab – Volume 8, 2020 103 ARCHITECTURAL FEATURES OF THE EARLY HARAPPAN FORTS Umesh Kumar Singh ABSTRACT What is generally called the Indus or the Harappan Civilization or Culture and used as interchangeable terms for the fifth millennium BCE Bronze Age Indian Civilization. Cunningham (1924: 242) referred vaguely to the remains of the walled town of Harappa and Masson (1842, I: 452) had camped in front of the village and ruinous brick castle. Wheeler (1947: 61) mentions it would appear from the context of Cunningham and Masson intended merely to distinguish the high mounds of the site from the vestiges of occupation on the lower ground round about and the latter doubt less the small Moghul fort which now encloses the police station on the eastern flank of the site. Burnes, about 1831, has referred to a ruined citadel on the river towards the northern side (Burnes 1834: 137). Marshall (1931) and Mackay (1938) also suspected of identifying Burnes citadel and Mackay (1938) had to suspend his excavations whilst in the act of examining a substantial structure which he was inclined to think was a part of city wall. Wheeler had discovered a limited number of pottery fragments from the pre- defense levels at Harappa in 1946 but the evidence was too meager to provoke serious discussion. The problem of origin and epi-centre of the Harappa Culture has confronted scholars since its discovery and in this context the most startling archaeological discoveries made and reported by Rafique Mughal (1990) is very significant and is a matter of further research work. -

Dating the Adoption of Rice, Millet and Tropical Pulses at Indus Civilisation

Feeding ancient cities in South Asia: dating the adoption of rice, millet and tropical pulses in the Indus civilisation C.A. Petrie1,*, J. Bates1, T. Higham2 & R.N. Singh3 1 Division of Archaeology, University of Cambridge, Downing Street, Cambridge CB2 3DZ, UK 2 RLAHA, Oxford University, Dyson Perrins Building, South Parks Road, Oxford OX1 3QY, UK 3 Department of AIHC & Archaeology, Banaras Hindu University, Varanasi 221005, India * Author for correspondence (Email: [email protected]) <OPEN ACCESS CC-BY-NC-ND> Received: 11 March 2016; Accepted: 2 June 2016; Revised: 9 June 2016 <LOCATION MAP><6.5cm colour, place to left of abstract and wrap text around> The first direct absolute dates for the exploitation of several summer crops by Indus populations are presented. These include rice, millets and three tropical pulse species at two settlements in the hinterland of the urban site of Rakhigarhi. The dates confirm the role of native summer domesticates in the rise of Indus cities. They demonstrate that, from their earliest phases, a range of crops and variable strategies, including multi-cropping were used to feed different urban centres. This has important implications for our understanding of the development of the earliest cities in South Asia, particularly the organisation of labour and provisioning throughout the year. Keywords: South Asia, Indus civilisation, rice, millet, pulses Introduction The ability to produce and control agricultural surpluses was a fundamental factor in the rise of the earliest complex societies and cities, but there was considerable variability in the crops that were exploited in different regions. The populations of South Asia’s Indus civilisation occupied a climatically and environmentally diverse region that benefitted from both winter and summer rainfall systems, with the latter coming via the Indian summer monsoon (Figure 1; Wright 2010; Petrie et al. -

Book Reviews

BOOK REVIEWS Indian Beads: A Cultural aud Technological Study. Shantaram Bha1chandra Deo. Pune: Deccan College Postgraduate and Research Institute, 2000. 205 pp., 7 color, 37 b/w plates, 3 maps, 24 figures, bibliography, no index. Paper 600 rupees. No ISBN. Distinctive Beads in Ancient India. Maurya Jyotsna. BAR International Series 864. Oxford: Archaeopress, 2000. 122 pp., 1 map, 10 figures, 7 tables, bibliography, index. Paper cover. ISBN 1-84171-067-9. Amulets and Pendants in Ancient Maharashtra. Maurya Jyotsna. New Delhi: D. K. Printworld, 2000. 102 pp., 4 maps, 12 figures, 3 tables, bibliography, index. Cloth 220 rupees. ISBN 81-246-0158-5. Reviewed by PETER FRANCIS JR. (1945-2003), former Director of the Centerfor Bead Research, Lake Placid, New York India is one of the world's largest countries rate with him on a book. That project with one of its most ancient civilizations. never happened, as Dikshit passed away in Blessed with immense natural and human 19(}9, just before his own History (?f Indian resources. It is no surprise that it is a lead Class was published. ing source of beads in both ancient and Deo received a fellowship from the In modern times. Only China is larger and as dian Council of Historical Research to ancient, but the Chinese have never been study and prepare a manuscript on Indian as interested in beads as have the Indians. beads during the years 1985 to 1988. He The Indian subcontinent has been unparal worked on the project for many years, long leled in terms of bead making, bead trad after the period of the fellowship.