Download Full Version of Author's Notes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mumbai's Original Inhabitants Fear World's Tallest Statue

HEALTH FRIDAY, FEBRUARY 24, 2017 Mumbai’s original inhabitants fear world’s tallest statue MUMBAI: A fitting tribute to a local legend a gross waste of money which would be of fish to sell at markets and feed their fami- cause immense harm to a vibrant marine or a grotesque misuse of money? The deci- better spent on improving health, educa- lies. Residents say disruption caused by ecosystem. “There’s a huge diversity of fish, sion to build the world’s tallest statue just tion and infrastructure in the teeming construction will decimate their fishing fauna and invertebrates there. Fish catches, off Mumbai’s coast has divided the city. But metropolis of more than 20 million people. stocks-including pomfret, Bombay macker- sewage, and tidal currents will change,” the traditional Koli community, who el, seer fish, prawns, and crabs-while heavy wildlife biologist Anand Pendharkar said. depend on fishing for their livelihoods, fear Environmental destruction traffic ferrying tourists from three terminals “It’s going to affect the food base of the they will be worst hit by the construction, A petition on the change.org website will block access to the sea and disrupt city, it’s going to affect the economy. There warning that it threatens their centuries- opposing the bronze statue, which will wave patterns. is going to be a huge amount of damage.” old existence. India will spend 36 billion Critics question why Mumbai needs such rupees ($530 million) on the controversial a lavish statute when the city already has memorial to 17th century Hindu warrior several smaller Shivaji memorials. -

Stay Safe at Home

Stay safe at home. We have strengthened our online platforms with an aim to serve your needs uniterruptedly. Access our websites: www.nipponindiamf.com www.nipponindiapms.com (Chat feature available) www.nipponindiaetf.com www.nipponindiaaif.com Click to download our mobile apps: Nippon India Mutual Fund | Simply Save App For any further queries, contact us at [email protected] Mutual Fund investments are subject to market risks, read all scheme related documents carefully. INDIA-CHINA: TENSION PEAKS IN LADAKH DIGITAL ISSUE www.outlookindia.com June 8, 2020 What After Home? Lakhs of migrants have returned to their villages. OUTLOOK tracks them to find out what lies ahead. Mohammad Saiyub’s friend Amrit Kumar died on their long journey home. Right, Saiyub in his village Devari in UP. RNI NO. 7044/1961 MANAGING EDITOR, OUTLOOK FROM THE EDITOR Returning to RUBEN BANERJEE the Returnees EDITOR IN CHIEF and apathy have been their constant companions since then. As entire families—the old, infirm and the ailing included—attempt to plod back home, they have been sub- NDIA is working from home; jected to ill-treatment and untold indignities by the police Bharat is walking home—the short for violating the lockdown. Humiliation after humiliation tweet by a friend summing up was heaped upon them endlessly as they walked, cycled and what we, as a locked-down nation, hitchhiked long distances. They were sprayed with disin- have been witnessing over the past fectants and fleeced by greedy transporters for painful two months was definitely smart. rides on the back of trucks and tempos. -

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT NORTHERN DISTRICT of INDIANA SOUTH BEND DIVISION in Re FEDEX GROUND PACKAGE SYSTEM, INC., EMPLOYMEN

USDC IN/ND case 3:05-md-00527-RLM-MGG document 3279 filed 03/22/19 page 1 of 354 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT NORTHERN DISTRICT OF INDIANA SOUTH BEND DIVISION ) Case No. 3:05-MD-527 RLM In re FEDEX GROUND PACKAGE ) (MDL 1700) SYSTEM, INC., EMPLOYMENT ) PRACTICES LITIGATION ) ) ) THIS DOCUMENT RELATES TO: ) ) Carlene Craig, et. al. v. FedEx Case No. 3:05-cv-530 RLM ) Ground Package Systems, Inc., ) ) PROPOSED FINAL APPROVAL ORDER This matter came before the Court for hearing on March 11, 2019, to consider final approval of the proposed ERISA Class Action Settlement reached by and between Plaintiffs Leo Rittenhouse, Jeff Bramlage, Lawrence Liable, Kent Whistler, Mike Moore, Keith Berry, Matthew Cook, Heidi Law, Sylvia O’Brien, Neal Bergkamp, and Dominic Lupo1 (collectively, “the Named Plaintiffs”), on behalf of themselves and the Certified Class, and Defendant FedEx Ground Package System, Inc. (“FXG”) (collectively, “the Parties”), the terms of which Settlement are set forth in the Class Action Settlement Agreement (the “Settlement Agreement”) attached as Exhibit A to the Joint Declaration of Co-Lead Counsel in support of Preliminary Approval of the Kansas Class Action 1 Carlene Craig withdrew as a Named Plaintiff on November 29, 2006. See MDL Doc. No. 409. Named Plaintiffs Ronald Perry and Alan Pacheco are not movants for final approval and filed an objection [MDL Doc. Nos. 3251/3261]. USDC IN/ND case 3:05-md-00527-RLM-MGG document 3279 filed 03/22/19 page 2 of 354 Settlement [MDL Doc. No. 3154-1]. Also before the Court is ERISA Plaintiffs’ Unopposed Motion for Attorney’s Fees and for Payment of Service Awards to the Named Plaintiffs, filed with the Court on October 19, 2018 [MDL Doc. -

Times City the Times of India, Mumbai | Wednesday, February 18, 2015

TIMES CITY THE TIMES OF INDIA, MUMBAI | WEDNESDAY, FEBRUARY 18, 2015 HOW TO DOWNLOAD Get the free Alive App: STEP 2 Picture Scan: Open the Alive app on your phone and scan the STEP 3 Watch the Available on select android (version 4.0 and AND USE ALIVE APP Give a missed call to picture by focusing your phone’s camera on it. QR Code Scan: Open the photo come Alive. above), iOS (version 7.0 and above), BB 18001023324 or visit Alive app and tap on the ‘QR code’ tab at the bottom of the screen. Fill the View it and share (version 5.0 and above), Symbian (version S60 PAGES16 alivear.com from your mobile phone QR code inside the square and hold still. Available on iOS and Android only. it with friends. and above), Windows (version 7.5 and above) 400 bars, pubs & restaurants could get to stay open 24x7 had assured them he would involve revenue and jobs, but without incon- State Set To Amend Laws In Monsoon Session; Hoteliers’ Body all stakeholders before deciding the veniencing residents. “The legisla- line of amendments in laws such as tion can allow those places which Meets Netas, Tells Them Move Will Bring In Revenue, Tourists the Shops and Establishments Act. have an inbuilt mechanism to take HRAWI office-bearers Gogi Singh, care of security, traffic, etc. in com- Chittaranjan.Tembhekar night entertainment zones for ment. The police have said they have Dilip Datwani and Pradip Shetty mercial areas to serve through the @timesgroup.com Mumbaikars as well as tourists. -

Joe Rosochacki - Poems

Poetry Series Joe Rosochacki - poems - Publication Date: 2015 Publisher: Poemhunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive Joe Rosochacki(April 8,1954) Although I am a musician, (BM in guitar performance & MA in Music Theory- literature, Eastern Michigan University) guitarist-composer- teacher, I often dabbled with lyrics and continued with my observations that I had written before in the mid-eighties My Observations are mostly prose with poetic lilt. Observations include historical facts, conjecture, objective and subjective views and things that perplex me in life. The Observations that I write are more or less Op. Ed. in format. Although I grew up in Hamtramck, Michigan in the US my current residence is now in Cumby, Texas and I am happily married to my wife, Judy. I invite to listen to my guitar works www.PoemHunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive 1 A Dead Hand You got to know when to hold ‘em, know when to fold ‘em, Know when to walk away and know when to run. You never count your money when you're sittin at the table. There'll be time enough for countin' when the dealins' done. David Reese too young to fold, David Reese a popular jack of all trades when it came to poker, The bluffing, the betting, the skill that he played poker, - was his ace of his sleeve. He played poker without deuces wild, not needing Jokers. To bad his lungs were not flushed out for him to breathe, Was is the casino smoke? Or was it his lifestyle in general? But whatever the circumstance was, he cashed out to soon, he had gone to see his maker, He was relatively young far from being too old. -

Rights of Transgender Adolescents to Sex Reassignment Treatment

THE DOCTOR WON'T SEE YOU NOW: RIGHTS OF TRANSGENDER ADOLESCENTS TO SEX REASSIGNMENT TREATMENT SONJA SHIELD* I. INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................... 362 H . DEFINITIO NS ........................................................................................................ 365 III. THE HARMS SUFFERED BY TRANSGENDER ADOLESCENTS CREATE A NEED FOR EARLY TRANSITION .................................................... 367 A. DISCRIMINATION AND HARASSMENT FACED BY TRANSGENDER YOUTH .............. 367 1. School-based violence and harassment............................................................. 368 2. Discriminationby parents and thefoster care system ....................................... 372 3. Homelessness, poverty, and criminalization...................................................... 375 B. PHYSICAL AND MENTAL EFFECTS OF DELAYED TRANSITION ............................... 378 1. Puberty and physical changes ........................................................................... 378 2. M ental health issues ........................................................................................... 382 IV. MEDICAL AND PSYCHIATRIC RESPONSES TO TRANSGENDER PEOPLE ........................................................................................ 385 A. GENDER IDENTITY DISORDER TREATMENT ........................................................... 386 B. FEARS OF POST-TREATMENT REGRET ................................................................... -

2013 Sex Work and the Senate Swedish Meatballs | a Paper Bird.Pdf

Sex work and the Senate: Swedish meatballs | a paper bird 9/14/13 9:06 AM a paper bird Un pajaro de papel en el pecho / Dice que el tiempo de los besos no ha llegado Sex work and the Senate: Swedish meatballs Posted on 14 September 2013 — Ny spännande möbel från IKEA! Med IKEAs nya PERVERS ställning kan man hotta upp sitt sexförhållande. Go ahead, translate that. There was a time when “the Swedish model” meant either some girl who was dating Leonardo DiCaprio, or a literary anthology of IKEA assembly instructions. Those were innocent days. Now it’s all about sex, and not of the unthreatening DiCaprio variety. Specifically, it refers to what Swedes call the Sexköpslagen or Sex Purchase Law, a 14-year-old act saying that no man kan hotta upp sitt sexförhållande with the use of money. The provision criminalizing the buyer but not the seller of sexual services has become a pattern for pushing legal repression elsewhere, including Canada, England, Scotland, and most recently Ireland. Now even the US Senate is under its influence. David Vitter is a boringly conservative Louisiana Republican. For the most part, he’s there to vote for whatever the oil industry tells him to, though he spikes up the monotony a bit by fighting same-sex marriage, crusading against gambling, and getting lewd women to dress him up in diapers. http://paper-bird.net/2013/09/14/sex-work-and-the-senate-swedish-meatballs/ Page 1 of 9 Sex work and the Senate: Swedish meatballs | a paper bird 9/14/13 9:06 AM The latter propensity started to make headlines during his first term in the Senate, in 2007. -

CHAPTER 3 the Classical School of Criminological Thought

The Classical CHAPTER 3 School of Criminological Thought Wally Skalij/Los Angeles Times/Getty Images distribute or post, copy, not Do Copyright ©2018 by SAGE Publications, Inc. This work may not be reproduced or distributed in any form or by any means without express written permission of the publisher. Introduction LEARNING A 2009 report from the Death Penalty Information Center, citing a study OBJECTIVES based on FBI data and other national reports, showed that states with the death penalty have consistently higher murder rates than states without the death penalty.4 The report highlighted the fact that if the death penalty were As you read this chapter, acting as a deterrent, the gap between these two groups of states would be consider the following topics: expected to converge, or at least lessen over time. But that has not been the case. In fact, this disparity in murder rates has actually grown over the past • Identify the primitive two decades, with states allowing the death penalty having a 42% higher types of “theories” murder rate (as of 2007) compared with states that do not—up from only explaining why 4% in 1990. individuals committed violent and other Thus, it appears that in terms of deterrence theory, at least when it comes deviant acts for most to the death penalty, such potential punishment is not an effective deterrent. of human civilization. This chapter deals with the various issues and factors that go into offend- • Describe how the ers’ decision-making about committing crime. While many would likely Age of Enlightenment anticipate that potential murderers in states with the death penalty would be drastically altered the deterred from committing such offenses, this is clearly not the case, given theories for how and the findings of the study discussed above. -

Maharashtra Vidhan Sabha Candidate List.Xlsx

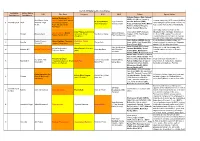

List of All Maharashtra Candidates Lok Sabha Vidhan Sabha BJP Shiv Sena Congress NCP MNS Others Special Notes Constituency Constituency Vishram Padam, (Raju Jaiswal) Aaditya Thackeray (Sunil (BSP), Adv. Mitesh Varshney, Sunil Rane, Smita Shinde, Sachin Ahir, Ashish Coastal road (kolis), BDD chawls (MHADA Dr. Suresh Mane Vijay Kudtarkar, Gautam Gaikwad (VBA), 1 Mumbai South Worli Ambekar, Arjun Chemburkar, Kishori rules changed to allow forced eviction), No (Kiran Pawaskar) Sanjay Jamdar Prateep Hawaldar (PJP), Milind Meghe Pednekar, Snehalata ICU nearby, Markets for selling products. Kamble (National Peoples Ambekar) Party), Santosh Bansode Sewri Jetty construction as it is in a Uday Phanasekar (Manoj Vijay Jadhav (BSP), Narayan dicapitated state, Shortage of doctors at Ajay Choudhary (Dagdu Santosh Nalaode, 2 Shivadi Shalaka Salvi Jamsutkar, Smita Nandkumar Katkar Ghagare (CPI), Chandrakant the Sewri GTB hospital, Protection of Sakpal, Sachin Ahir) Bala Nandgaonkar Choudhari) Desai (CPI) coastal habitat and flamingo's in the area, Mumbai Trans Harbor Link construction. Waris Pathan (AIMIM), Geeta Illegal buildings, building collapses in Madhu Chavan, Yamini Jadhav (Yashwant Madhukar Chavan 3 Byculla Sanjay Naik Gawli (ABS), Rais Shaikh (SP), chawls, protests by residents of Nagpada Shaina NC Jadhav, Sachin Ahir) (Anna) Pravin Pawar (BSP) against BMC building demolitions Abhat Kathale (NYP), Arjun Adv. Archit Jaykar, Swing vote, residents unhappy with Arvind Dudhwadkar, Heera Devasi (Susieben Jadhav (BHAMPA), Vishal 4 Malabar Hill Mangal -

Myths and Realities Poster

Please copy and distribute this poster freely Text and poster design by Norma JeanAlmodovar ©2013 NY Governor Eliot Spitzer rich, powerful former NY Top ISWFACE Presents: Prosecutor- prosecuted ‘prostitution rings’ with a vengeance- and as governor, enacted strong ‘anti- human (sex) trafficking laws to deal with ‘modern day slavery’- caught using the services of very expensive call girls- flying them across state lines to wherever he was going to be - in Florida, DC - etc. in violation of the Mann Act- FELONY- resigned from officeA FEDERAL but NOT arrested Meet OurCarl XVI ‘Johns’Gustaf or prosecuted, while the madam who provided him Meet OurKing of Sweden‘Johns’ with his ‘sex slaves’ went to prison. 2008 If even the king of Sweden patronizes sex workers, in a country which criminalizes the clients of prostitutes, how can Rev. George Rekers prostitution abolitionists believe that such laws a prominent anti-gay activist who co-founded the conservative designed to ‘end the Family Research Council, was demand’ will have any impact on the average caught returning from a 10-day client of prostitutes? trip to Europe with a male escort he found on Rentboy.com, which 2011 is exactly what2010 it sounds like. Appointed Government Official Randall Tobias Christian conservative- director of U.S. Foreign Assistance and administrator of the U.S. Agency for International Development, was named by President Bush as the first U.S. Global AIDS Coordinator, with the rank of ambassador, which refused to grant funding to any non profit or NGO which supported decriminalization of prostitution. Claims that when he had “gals come over to the condo to give me a massage," there was no sex involved. -

Front Matter

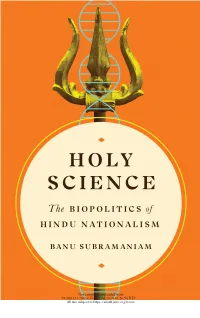

This content downloaded from 98.164.221.200 on Fri, 17 Jul 2020 16:26:54 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms Feminist technosciences Rebecca Herzig and Banu Subramaniam, Series Editors This content downloaded from 98.164.221.200 on Fri, 17 Jul 2020 16:26:54 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms This content downloaded from 98.164.221.200 on Fri, 17 Jul 2020 16:26:54 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms HOLY SCIENCE THE BIOPOLITICS OF HINDU NATIONALISM Banu suBramaniam university oF Washington Press Seattle This content downloaded from 98.164.221.200 on Fri, 17 Jul 2020 16:26:54 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms Financial support for the publication of Holy Science was provided by the Office of the Vice Chancellor for Research and Engagement, University of Massachusetts Amherst. Copyright © 2019 by the University of Washington Press Printed and bound in the United States of America Interior design by Katrina Noble Composed in Iowan Old Style, typeface designed by John Downer 23 22 21 20 19 5 4 3 2 1 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. university oF Washington Press www.washington.edu/uwpress LiBrary oF congress cataLoging-in-Publication Data Names: Subramaniam, Banu, 1966- author. Title: Holy science : the biopolitics of Hindu nationalism / Banu Subramaniam. -

Pathak Stresses on Spreading Awareness About Road Safety Gy NEWS SERVICE Motion Adopted by the JAMMU, JAN

For Daily English Newspaper RNI No. JKENG/2013/48845 TITLE CODE: JKENG-00999 Advertisement in Golden Yug –– Contact –– 0191-2464590 For Booking of Copies of Golden Yug Golden Yug –– Contact –– e-mail: [email protected], [email protected] Website: www.goldenyug.com 94191-88950 Vol. 3 ISSUE NO. 16 Jammu, Sunday 18, January 2015 PAGES 8 PRICE RS. 2/- Postal Regd. No. L-29/JK-509/13-15 Governor interacts with members of Civil Mufti Mohammad Sayeed meets Governor Hideout busted in Tral Society, Associations on various issues related gy NEWS SERVICE NN Vohra over J&K govt formation SRINAgAR, JAN. to relief & rehabilitation of the flood affected gy NEWS SERVICE stood to have discussed her party is not averse to Governor Vohra had 17: Police and security JAMMU, JAN. 17: government formation and joining hands with BJP. earlier set January 19 forces busted a hideout in Asks the adm for quick redressal of grievances Amid an impasse over gov - political stalemate in the The party had on deadline for formation of the Tral forests of South gy NEWS SERVICE ernment formation, PDP state. The details of the January 14 declined to the government in the SRINAgAR, JAN. 17: patron Mufti Mohammad meeting are not known," the accept the offer of NC for state where Peoples Kashmir. On a tip off, Governor, N.N. Vohra inter - Sayeed met with Jammu source said. PDP support to formation of Democratic Party (PDP) Awantipora police, 42 RR acted with the stakeholders and Kashmir Governor NN Spokesperson Nayeem PDP led government in the has emerged as the largest and 185 Bn CRPF of tourism, traders, hand - Vohra and the two are Akhtar said he was not state.