Progress in Older Scots Philology A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

'Country', 'Land', 'Nation': Key Anglo English Words for Talking and Thinking About People in Places

8 ‘Country’, ‘land’, ‘nation’: Key Anglo English words for talking and thinking about people in places Cliff Goddard Griffith University, Australia [email protected] Abstract The importance of the words ‘country’, ‘land’ and ‘nation’, and their derivatives, in Anglophone public and political discourses is obvious. Indeed, it would be no exaggeration to say that without the support of words like these, discourses of nationalism, patriotism, immigration, international affairs, land rights, and post/anti- colonialism would be literally impossible. This is a corpus-assisted, lexical-semantic study of the English words ‘country’, ‘land’ and ‘nation’, using the NSM technique of paraphrase in terms of simple, cross- translatable words (Goddard & Wierzbicka 2014). It builds on Anna Wierzbicka’s (1997) seminal study of “homeland” and related concepts in European languages, as well as more recent NSM works (e.g. Bromhead 2011, 2018; Levisen & Waters 2017) that have explored ways in which discursively powerful words encapsulate historically and culturally contingent assumptions about relationships between people and places. The primary focus is on conceptual analysis, lexical polysemy, phraseology and discursive formation in mainstream Anglo English, but the study also touches on one specifically Australian phenomenon, which is the use of ‘country’ in a distinctive sense which originated in Aboriginal English, e.g. in expressions like ‘my grandfather’s country’ and ‘looking after country’. This highlights how Anglo English words can be semantically “re-purposed” in postcolonial and anti-colonial discourses. Keywords: lexical semantics, NSM, ‘nation’ concept, Anglo English, Australian English, Aboriginal English. 1. Orientation and methodology The importance of the words country, land and nation, and their derivatives, in Anglophone public and political discourses is obvious. -

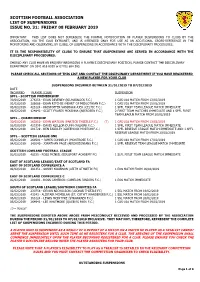

Scottish Football Association List of Suspensions Issue No

SCOTTISH FOOTBALL ASSOCIATION LIST OF SUSPENSIONS ISSUE NO. 31: FRIDAY 08 FEBRUARY 2019 IMPORTANT – THIS LIST DOES NOT SUPERSEDE THE FORMAL NOTIFICATION OF PLAYER SUSPENSIONS TO CLUBS BY THE ASSOCIATION, VIA THE CLUB EXTRANET, AND IS INTENDED ONLY FOR USE AS AN ADDITIONAL CROSS-REFERENCE IN THE MONITORING AND OBSERVING, BY CLUBS, OF SUSPENSIONS IN ACCORDANCE WITH THE DISCIPLINARY PROCEDURES. IT IS THE RESPONSIBILITY OF CLUBS TO ENSURE THAT SUSPENSIONS ARE SERVED IN ACCORDANCE WITH THE DISCIPLINARY PROCEDURES. SHOULD ANY CLUB HAVE AN ENQUIRY REGARDING A PLAYER’S DISCIPLINARY POSITION, PLEASE CONTACT THE DISCIPLINARY DEPARTMENT ON 0141 616 6018 or 07702 864 165. PLEASE CHECK ALL SECTIONS OF THIS LIST AND CONTACT THE DISIPLINARY DEPARTMENT IF YOU HAVE REGISTERED A NEW PLAYER FOR YOUR CLUB SUSPENSIONS INCURRED BETWEEN 31/01/2019 TO 07/02/2019 DATE INCURRED PLAYER (CLUB) SUSPENSION SPFL - SCOTTISH PREMIERSHIP 30/01/2019 276256 - EUAN DEVENEY (KILMARNOCK F.C.) 1 CAS U18 MATCH FROM 13/02/2019 01/02/2019 386086 - DEAN RITCHIE (HEART OF MIDLOTHIAN F.C.) 1 CAS U18 MATCH FROM 15/02/2019 03/02/2019 423124 - KRISTOFFER VASSBAKK AJER (CELTIC F.C.) 1 SPFL FIRST TEAM LEAGUE MATCH IMMEDIATE 06/02/2019 124842 - SCOTT FRASER MCKENNA (ABERDEEN F.C.) 2 FIRST TEAM MATCHES IMMEDIATE AND 1 SPFL FIRST TEAM LEAGUE MATCH FROM 20/02/2019 SPFL – CHAMPIONSHIP 30/01/2019 260210 - DEAN WATSON (PARTICK THISTLE F.C.) (T) 1 CAS U18 MATCH FROM 13/02/2019 02/02/2019 425359 - DAVIS KEILLOR-DUNN (FALKIRK F.C.) 1 SPFL FIRST TEAM LEAGUE MATCH IMMEDIATE 06/02/2019 201729 - BEN -

Anglo-Saxon and Scots Invaders

Anglo-Saxon and Scots Invaders By around 410AD, the last of the Romans had left Britain to go back to Rome and England was left to look after itself for the first time in about 400 years. Emperor Honorius told the people to fight the Picts, Scots and Saxons who were attacking them, but the Brits were not good fighters. The Scots, who came from Ireland, invaded and took land in Scotland. The Scots split Scotland into 4 separate places that were named Dal Riata, Pictland, Strathclyde and Bernicia. The Picts (the people already living in Scotland) and the Scots were always trying to get into England. It was hard for the people in England to fight them off without help from the Romans. The Picts and Scots are said to have jumped over Hadrian’s Wall, killing everyone in their way. The British king found it hard to get his men to stop the Picts and Scots. He was worried they would take over in England because they were excellent fighters. Then he had an idea how he could keep the Picts and Scots out. He asked two brothers called Hengest and Horsa from Jutland to come and fight for him and keep England safe from the Picts and Scots. Hengest and Horsa did help to keep the Picts and Scots out, but they liked England and they wanted to stay. They knew that the people in England were not strong fighters so they would be easy to beat. Hengest and Horsa brought more men to fight for England and over time they won. -

SCOTTISH TEXT SOCIETY Old Series

SCOTTISH TEXT SOCIETY Old Series Skeat, W.W. ed., The kingis quiar: together with A ballad of good counsel: by King James I of Scotland, Scottish Text Society, Old Series, 1 (1884) Small, J. ed., The poems of William Dunbar. Vol. I, Scottish Text Society, Old Series, 2 (1883) Gregor, W. ed., Ane treatise callit The court of Venus, deuidit into four buikis. Newlie compylit be Iohne Rolland in Dalkeith, 1575, Scottish Text Society, Old Series, 3 (1884) Small, J. ed., The poems of William Dunbar. Vol. II, Scottish Text Society, Old Series, 4 (1893) Cody, E.G. ed., The historie of Scotland wrytten first in Latin by the most reuerend and worthy Jhone Leslie, Bishop of Rosse, and translated in Scottish by Father James Dalrymple, religious in the Scottis Cloister of Regensburg, the zeare of God, 1596. Vol. I, Scottish Text Society, Old Series, 5 (1888) Moir, J. ed., The actis and deisis of the illustere and vailzeand campioun Schir William Wallace, knicht of Ellerslie. By Henry the Minstrel, commonly known ad Blind Harry. Vol. I, Scottish Text Society, Old Series, 6 (1889) Moir, J. ed., The actis and deisis of the illustere and vailzeand campioun Schir William Wallace, knicht of Ellerslie. By Henry the Minstrel, commonly known ad Blind Harry. Vol. II, Scottish Text Society, Old Series, 7 (1889) McNeill, G.P. ed., Sir Tristrem, Scottish Text Society, Old Series, 8 (1886) Cranstoun, J. ed., The Poems of Alexander Montgomerie. Vol. I, Scottish Text Society, Old Series, 9 (1887) Cranstoun, J. ed., The Poems of Alexander Montgomerie. Vol. -

An Anglo-European Perspective on Industrial Relations Research

ARTIKEL Richard Hyman An Anglo-European Perspective on Industrial Relations Research In this paper I review approaches to industrial relations research in Britain and in continental western Europe. My aim is to explore the diversity of traditions towards the analysis of the world of work, not only within Europe but also between Britain and the USA. My core argument differs in important respects from that of Bruce Kaufman: if the field of ‘traditional’ industrial relations scholarship is in decline and disarray in America, the situation in Europe is very different: recent years have seen moves towards a fruitful synthesis of the diversity of understandings of our field of study. What Do We Mean by ‘Industrial Relations’? The study of industrial relations, as we understand it today, dates back more than a century, with the work of the Webbs in Britain and Commons in the USA. The field of study which they pioneered, with its focus on the rules which govern the employment relationship, the institutions involved in this process, and the power dynamics among the main agents of regulation, evolved over the decades Richard Hyman är professor i Industrial Relations, Department of Employment in an ad hoc fashion, responding to the Relations and Orgnisational Behaviour, pragmatic requirements of governments and London School of Economics. managements rather than to any underlying [email protected] intellectual rationale. The field acquired the label ’industrial relations’ more or less as an historical accident, following the appointment by the US Congress in 1912 of a ’Commission on Industrial Relations’. In many respects the title is a misnomer: for the focus of research and analysis normally covers all employment (not just ‘industry’) and not all ‘relations’ (only those regulated by specific institutional arrangements). -

AJ Aitken a History of Scots

A. J. Aitken A history of Scots (1985)1 Edited by Caroline Macafee Editor’s Introduction In his ‘Sources of the vocabulary of Older Scots’ (1954: n. 7; 2015), AJA had remarked on the distribution of Scandinavian loanwords in Scots, and deduced from this that the language had been influenced by population movements from the North of England. In his ‘History of Scots’ for the introduction to The Concise Scots Dictionary, he follows the historian Geoffrey Barrow (1980) in seeing Scots as descended primarily from the Anglo-Danish of the North of England, with only a marginal role for the Old English introduced earlier into the South-East of Scotland. AJA concludes with some suggestions for further reading: this section has been omitted, as it is now, naturally, out of date. For a much fuller and more detailed history up to 1700, incorporating much of AJA’s own work on the Older Scots period, the reader is referred to Macafee and †Aitken (2002). Two textual anthologies also offer historical treatments of the language: Görlach (2002) and, for Older Scots, Smith (2012). Corbett et al. eds. (2003) gives an accessible overview of the language, and a more detailed linguistic treatment can be found in Jones ed. (1997). How to cite this paper (adapt to the desired style): Aitken, A. J. (1985, 2015) ‘A history of Scots’, in †A. J. Aitken, ed. Caroline Macafee, ‘Collected Writings on the Scots Language’ (2015), [online] Scots Language Centre http://medio.scotslanguage.com/library/document/aitken/A_history_of_Scots_(1985) (accessed DATE). Originally published in the Introduction, The Concise Scots Dictionary, ed.-in-chief Mairi Robinson (Aberdeen University Press, 1985, now published Edinburgh University Press), ix-xvi. -

THE SCOTS LANGUAGE in DRAMA by David Purves

THE SCOTS LANGUAGE IN DRAMA by David Purves THE SCOTS LANGUAGE IN DRAMA by David Purves INTRODUCTION The Scots language is a valuable, though neglected, dramatic resource which is an important part of the national heritage. In any country which aspires to nationhood, the function of the theatre is to extend awareness at a universal level in the context of the native cultural heritage. A view of human relations has to be presented from the country’s own national perspective. In Scotland prior to the union of the Crowns in 1603, plays were certainly written with this end in view. For a period of nearly 400 years, the Scots have not been sure whether to regard themselves as a nation or not, and a bizarre impression is now sometimes given of a greater Government commitment to the cultures of other countries, than to Scotland’s indigenous culture. This attitude is reminiscent of the dismal cargo culture mentality now established in some remote islands in the Pacific, which is associated with the notion that anything deposited on the beach is good, as long as it comes from elsewhere. This paper is concerned with the use in drama of Scots as a language in its own right:, as an internally consistent register distinct from English, in which traditional linguistic features have not been ignored by the playwright. Whether the presence of a Scottish Parliament in the new millennium will rid us of this provincial mentality remains to be seen. However, it will restore to Scotland a national political voice, which will allow the problems discussed in this paper to be addressed. -

Anglo-American Merchants and Stratagems for Success in Spanish Imperial Markets, 1783-1807

Trinity University Digital Commons @ Trinity History Faculty Research History Department 1984 Anglo-American Merchants and Stratagems for Success in Spanish Imperial Markets, 1783-1807 Linda K. Salvucci Princeton University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.trinity.edu/hist_faculty Part of the History Commons Repository Citation Salvucci, L. K. (1984). Anglo-American merchants and stratagems for success in Spanish imperial markets, 1783-1807. In J. A. Barbier & A. J. Kuethe (Eds.), The north American role in the Spanish imperial economy, 1760-1819 (pp. 127-133). Manchester University Press. This Contribution to Book is brought to you for free and open access by the History Department at Digital Commons @ Trinity. It has been accepted for inclusion in History Faculty Research by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Trinity. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CHAPTER SIX Anglo-American merchants andstratagems for success in Spanish imperial markets, 1783-1807* But the Spanish Colonies, being wholly cloatbed and in a greatdegree fed by our nation, should they like the tyger be suffered to cripple the band whose bounty feed them? Hasnot the secondnation on the Globe in commercial tonnage, and thefust inexports forthe necessaries of life, a right to demand with firmness,the respect due to her Flag and Citizens ... 7 When Josiah Blakeley, consul of the United States at Santiago de Cuba, wrote these lines to Secretary of State James Madison on November 1, 1801 he had recently been jailed by administrators on that island.1 This remarkable situation notwithstanding, his sentiments still neatly express the paradox of trade between the United States and Spanish Caribbean ports. -

126613688.23.Pdf

Sts. SHV lift ,*2f SCOTTISH HISTORY SOCIETY FOURTH SERIES VOLUME 12 Calendar of Papal Letters to Scotland of Clement VII of Avignon 1378-1394 Dr. Annie I. Dunlop CALENDAR OF Papal Letters to Scotland of Clement VII of Avignon 1378-1394 edited by Charles Burns ★ Annie I. Dunlop (1897-1973): a Memoir by Ian B. Cowan EDINBURGH printed for the Scottish History Society by T. AND A. CONSTABLE LTD 1976 Scottish History Society 1976 SIO^MY^ c 19 77 ,5 ISBN 9500260 8 5 Printed in Great Britain PREFACE The Great Schism, which originated in a disputed papal election, has always been regarded as one of the most crucial periods in the history of western Christendom, and to this day that election remains the greatest unresolved controversy of the later Middle Ages. The stand taken by the Scottish nation throughout the Schism was particu- larly significant, yet, until recently, Scottish historians had explored only inadequately the original sources existing in the Vatican Archives. During the academic year 1961-2, the University of Glasgow awarded me a research scholarship with the specific aim of examining the letter-books, or registers, of one of the rival popes, and of noting systematically all the entries concerning Scotland. A microfilm of this source material is deposited with the Department of Scottish History. This project was instrumental in introducing me to the late Dr Annie I. Dunlop. It won her immediate and enthusiastic approval and she followed its progress with lively interest. Only a few months before her death, Dr Dunlop asked me, if I was still working hard for Scotland ! This Calendar of Papal Letters of Clement vn of Avignon relating to Scotland is the result of that work. -

July 1916 Part 1

The Scottish Historical Review VOL. XIIL, No. 52 JULY 1916 A Chapter Election at St. Andrews in 1417 Formulare compiled by John Lauder, who was secretary to THEAndrew Forman, Archbishop of St. Andrews, served for a time under Gavin Dunbar, Archbishop of Glasgow, became chief secretary to Cardinal Beaton, and ended his career under Archbishop Hamilton about 1552, contains almost exclusively contemporary documents. It is well known that in this volume the University of St. Andrews possesses a document of unique value for students of Scottish history on the eve of the Refor- mation. But in the course of his practice Lauder came across a few writs belonging to an earlier period which interested him, and which he took the trouble to incorporate. One of these, entered at folio 267, purports to be the instrument drawn up on the election of James de Haddenstoun to the Priory of St. Andrews. The compiler of a book of styles was not thinking of the historian as he wrote. Consequently there is an irritating absence of names and dates occasional inadvertence but except by ; very frequently the initials at least are preserved, and the persons are not difficult to identify. In the present instance there is no reason to doubt that we have the copy of a genuine document belonging to the early part of the fifteenth century, just when Scotland was ques- tioning the allegiance which she had maintained to the anti-Pope Benedict XIIL that be The writ is a long one, and the Latin prolix. All can attempted here is by close paraphrase and occasional translation to give the reader an idea of the proceedings. -

Authentic Language

! " " #$% " $&'( ')*&& + + ,'-* # . / 0 1 *# $& " * # " " " * 2 *3 " 4 *# 4 55 5 * " " * *6 " " 77 .'%%)8'9:&0 * 7 4 "; 7 * *6 *# 2 .* * 0* " *6 1 " " *6 *# " *3 " *# " " *# 2 " " *! "; 4* $&'( <==* "* = >?<"< <<'-:@-$ 6 A9(%9'(@-99-@( 6 A9(%9'(@-99-(- 6A'-&&:9$' ! '&@9' Authentic Language Övdalsk, metapragmatic exchange and the margins of Sweden’s linguistic market David Karlander Centre for Research on Bilingualism Stockholm University Doctoral dissertation, 2017 Centre for Research on Bilingualism Stockholm University Copyright © David Budyński Karlander Printed and bound by Universitetsservice AB, Stockholm Correspondence: SE 106 91 Stockholm www.biling.su.se ISBN 978-91-7649-946-7 ISSN 1400-5921 Acknowledgements It would not have been possible to complete this work without the support and encouragement from a number of people. I owe them all my humble thanks. -

245X ANGUS Mcintosh LECTURE 7 January, 2008

1 ISSN 2046-245X ANGUS McINTOSH LECTURE 7 January, 2008 2 ‘Revisiting the makars’ Angus McIntosh was, as you have heard, president of the Scottish Text Society for twelve years from 1977 to 1989, and honorary president thereafter. Although of Scots parentage, as you can tell from his name, he wasn’t a Scot but was born, as he used to say, in the old kingdom of Deira, south of the Tyne, or perhaps Bernicia, depending on where you think the boundary lay. The Society was extraordinarily lucky to secure the services of such an immensely distinguished scholar. As Forbes Professor of English Language here at Edinburgh, he led what was surely the greatest department of English language in the world. 1986 saw the publication of the four-volume Linguistic Atlas of Later Medieval English, the huge project which he had masterminded since its inception in 1952. During his years as President of the STS he was also working tirelessly to sustain the Dictionary of the Older Scottish Tongue as chair of its Joint Council, a position he held for thirty years. The Scottish Text Society in the late seventies and eighties, when Angus was president, had an eminent Council, which included among others Jack Aitken, who was the backbone of the Dictionary of the Older Scottish Tongue, and his successor, Jim Stevenson; Tom Crawford and Matthew McDiarmid, from Aberdeen; David Daiches, Ronnie Jack, Emily Lyle and Jack MacQueen from Edinburgh; Rod Lyall and Alex Scott from Glasgow. Those were the days when 3 the teaching of older Scots literature and language flourished in the Scottish universities.