Cassandra Clare Created a Fantasy Realm and Aims to Maintain Her Rule

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Television Academy Awards

2019 Primetime Emmy® Awards Ballot Outstanding Comedy Series A.P. Bio Abby's After Life American Housewife American Vandal Arrested Development Atypical Ballers Barry Better Things The Big Bang Theory The Bisexual Black Monday black-ish Bless This Mess Boomerang Broad City Brockmire Brooklyn Nine-Nine Camping Casual Catastrophe Champaign ILL Cobra Kai The Conners The Cool Kids Corporate Crashing Crazy Ex-Girlfriend Dead To Me Detroiters Easy Fam Fleabag Forever Fresh Off The Boat Friends From College Future Man Get Shorty GLOW The Goldbergs The Good Place Grace And Frankie grown-ish The Guest Book Happy! High Maintenance Huge In France I’m Sorry Insatiable Insecure It's Always Sunny in Philadelphia Jane The Virgin Kidding The Kids Are Alright The Kominsky Method Last Man Standing The Last O.G. Life In Pieces Loudermilk Lunatics Man With A Plan The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel Modern Family Mom Mr Inbetween Murphy Brown The Neighborhood No Activity Now Apocalypse On My Block One Day At A Time The Other Two PEN15 Queen America Ramy The Ranch Rel Russian Doll Sally4Ever Santa Clarita Diet Schitt's Creek Schooled Shameless She's Gotta Have It Shrill Sideswiped Single Parents SMILF Speechless Splitting Up Together Stan Against Evil Superstore Tacoma FD The Tick Trial & Error Turn Up Charlie Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt Veep Vida Wayne Weird City What We Do in the Shadows Will & Grace You Me Her You're the Worst Young Sheldon Younger End of Category Outstanding Drama Series The Affair All American American Gods American Horror Story: Apocalypse American Soul Arrow Berlin Station Better Call Saul Billions Black Lightning Black Summer The Blacklist Blindspot Blue Bloods Bodyguard The Bold Type Bosch Bull Chambers Charmed The Chi Chicago Fire Chicago Med Chicago P.D. -

As Writers of Film and Television and Members of the Writers Guild Of

July 20, 2021 As writers of film and television and members of the Writers Guild of America, East and Writers Guild of America West, we understand the critical importance of a union contract. We are proud to stand in support of the editorial staff at MSNBC who have chosen to organize with the Writers Guild of America, East. We welcome you to the Guild and the labor movement. We encourage everyone to vote YES in the upcoming election so you can get to the bargaining table to have a say in your future. We work in scripted television and film, including many projects produced by NBC Universal. Through our union membership we have been able to negotiate fair compensation, excellent benefits, and basic fairness at work—all of which are enshrined in our union contract. We are ready to support you in your effort to do the same. We’re all in this together. Vote Union YES! In solidarity and support, Megan Abbott (THE DEUCE) John Aboud (HOME ECONOMICS) Daniel Abraham (THE EXPANSE) David Abramowitz (CAGNEY AND LACEY; HIGHLANDER; DAUGHTER OF THE STREETS) Jay Abramowitz (FULL HOUSE; MR. BELVEDERE; THE PARKERS) Gayle Abrams (FASIER; GILMORE GIRLS; 8 SIMPLE RULES) Kristen Acimovic (THE OPPOSITION WITH JORDAN KLEEPER) Peter Ackerman (THINGS YOU SHOULDN'T SAY PAST MIDNIGHT; ICE AGE; THE AMERICANS) Joan Ackermann (ARLISS) 1 Ilunga Adell (SANFORD & SON; WATCH YOUR MOUTH; MY BROTHER & ME) Dayo Adesokan (SUPERSTORE; YOUNG & HUNGRY; DOWNWARD DOG) Jonathan Adler (THE TONIGHT SHOW STARRING JIMMY FALLON) Erik Agard (THE CHASE) Zaike Airey (SWEET TOOTH) Rory Albanese (THE DAILY SHOW WITH JON STEWART; THE NIGHTLY SHOW WITH LARRY WILMORE) Chris Albers (LATE NIGHT WITH CONAN O'BRIEN; BORGIA) Lisa Albert (MAD MEN; HALT AND CATCH FIRE; UNREAL) Jerome Albrecht (THE LOVE BOAT) Georgianna Aldaco (MIRACLE WORKERS) Robert Alden (STREETWALKIN') Richard Alfieri (SIX DANCE LESSONS IN SIX WEEKS) Stephanie Allain (DEAR WHITE PEOPLE) A.C. -

Record 63 Independent Pilots Selected for the 12Th

Press Note – please find assets at the below links: Photos – https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/0B-lTENXjpYxaWmEtRTIzSVozcFU Trailers – https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLIUPrhfxAzsCs0VylfwQ-PEtiGDoQIKOT FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE RECORD 63 INDEPENDENT PILOTS SELECTED FOR THE 12TH ANNUAL NEW YORK TELEVISION FESTIVAL *** As Official Artists, Creators will Enjoy Opportunities with Network, Digital, Agency and Studio execs at October TV Fest Independent Pilot Competition Official Selections to be Screened for the Public from October 24-29, Including 42 World Festival Premieres [NEW YORK, NY, August 15, 2016] – The NYTVF (www.nytvf.com) today announced the Official Selections for its flagship Independent Pilot Competition (IPC). A record-high 63 original television and digital pilots and series will be presented for industry executives and TV fans at the 12th Annual New York Television Festival, including 42 world festival premieres, October 24-29, 2016 at The Helen Mills Theater and Event Space, with additional Festival events at the Tribeca Three Sixty° and SVA Theatre. The slate of in-competition projects was selected from the NYTVF's largest pool of pilot submissions ever: up more than 42 percent from the previous high. Festival organizers also noted that the selections are representative of creative voices across diverse demographics, with 59 percent having a woman in a core creative role (creator, writer, director and/or executive producer) and 43 percent including one or more persons of color above the line (core creative team and/or lead actor). “We were blown away by the talent and creativity of this year's submissions – across the board it was a record-setting year and we had an extremely difficult task in identifying the competition slate. -

EAGLE TV SCHEDULE Cable Subscriber Channel Numbers Follow

MONDAY EVENING MARCH 21, 2016 4 PM 4:30 5 PM 5:30 6 PM 6:30 7 PM 7:30 8 PM 8:30 9 PM 9:30 10 PM 10:30 11 PM 11:30 Blue Mountain 2-3ABN The Last Day of Prophecy Celebrating Life, Recovery 3ABN Today Anchors of Truth Carter Rpt. Carter Rpt. 3ABN Today ASI Conventions Books Book Battles 3-CBS CBS News News (N) Jeopardy (N) Wheel (N) Supergirl “Manhunter” (N) Scorpion (N) ’ Å NCIS: Los Angeles (N) ’ News (N) Late Show-Colbert James Corden Paid Prog. 4-ABC Today’s (N) ABC News Today’s (N) Mod Fam Dancing With the Stars (Season Premiere) (N) ’ (:01) Castle (N) ’ Å Today’s (N) (:35) Jimmy Kimmel Live Nightline (N) Hollywood TMZ Live (N) TV SCHEDULE ’ 5-MNT Name Game The Moms Millionaire Millionaire Law Order: CI Law & Order: SVU Law & Order: SVU Mod Fam How I Met Simpsons Anger Tosh.0 Anger EAGLE Cable subscriber channel numbers follow call names. Times may vary for satellite viewers 6-NBC KGW News at 4 (N) News (N) News (N) KGW News at 6 (N) Live at 7 (N) Inside (N) The Voice Mentors include Sean “Diddy” Combs. (N) (:01) Blindspot (N) ’ News (N) J. Fallon 7-CW Crime Watch Daily (N) ’ Two Men Two Men Seinfeld ’ Seinfeld ’ Mod Fam Mod Fam Crazy Ex-Girlfriend (N) ’ Jane the Virgin (N) ’ News (N) Hollywood How I Met How I Met 9-TBS Seinfeld ’ Seinfeld ’ Amer. Dad Amer. Dad Amer. Dad Amer. Dad Family Guy Family Guy Family Guy Amer. -

The Mortal Instruments Series, Cassandra Clare Peels Back the Glamour to Reveal the Magic That Is Usually Hidden from Us

MARGARET K. MCELDERRY BOOKS By Cassandra Clare ABOUT THE SERIES Anyone who has visited New York City can tell you that it’s a magical place. But what if the magic that resides there is more than hectic energy and a bunch of tourist-friendly sites...what if it’s real? What if there’s another layer to this world that most people can’t see, a layer that’s full of faeries and vampires, werewolves and demon hunters, protective runes and evil overlords? In The Mortal Instruments series, Cassandra Clare peels back the glamour to reveal the magic that is usually hidden from us. The Mortal Instruments series speaks to the outsider in all of us as we try to figure out who we are and how we fit into the world, without letting anyone know how scared we are. By finding a balance between the worlds of the mundane and the Shadowhunters, readers follow Clary as she defines what sort of adult she will be. She finds out who she loves, where she belongs, and what she’s willing to fight for. Discussion Questions 1. When Clary learns that Magnus Bane had erased her supernatural memories, she says that she had always felt like there was some- thing wrong with her. How much of this is because she didn’t know her history, and how much is caused—as Magnus says—by the simple fact that she’s a teenager? Does she belong in the Shadowhunter world? 2. How much of what mundanes see in this world is a glamour, constructed by those with magical powers? Why do these glamours exist? How do things change for Clary once she can see through them? 3. -

FREEFORM Offerings May 2019

April 24, 2019 FREEFORM RELEASES ITS NEW LINEUP OF TV OFFERINGS FOR MAY 2019 INCLUDING THE 2.5 HOUR SERIES FINALE OF ‘SHADOWHUNTERS’ AND THE SEASON FINALE OF ‘MARVEL’S CLOAK & DAGGER’ AND ‘PRETTY LITTLE LIARS: THE PERFECTIONISTS’ “Shadowhunters” Season 3B Photos Available Here Screener available Here Clips available Here May 6 (8:00-10:30 p.m. EDT) – EpisoDe #3021 – “Alliance”/EpisoDe #3022 – “All GooD Things…” – Series Finale In the first part of the series finale, Clary comes up with a plan that will bring Shadowhunters and Downworlders together, as Alec struggles for a way to help Magnus. In the second part of the series finale, Jonathan begins his reign of vengeful terror as the Shadowhunters try to find a way to stop him. With only one hope, Clary must make a sacrifice that could have long-lasting implications for all. Meanwhile, wedding bells are in the air for one special couple. “The BolD Type” Season 3 Photos Available Here Screeners Available Here Clips Available Here May 7 (8:00-9:01 p.m. EDT) – EpisoDe #3005 – “Technical Difficulties” Scarlet falls prey to a data hack, halting production of the dotcom and magazine and Jane and Jacqueline fear their investigation could be compromised as a result. Pressures escalate when Sutton and Richard host a dinner party. Meanwhile, Kat opens up to Tia as they begin her campaign. May 14 (8:00-9:01 p.m. EDT) – EpisoDe #3006 – “#TBT” The Scarlet email hack brings up memories of the trio’s first meeting four years ago, reminding them that together they can overcome anything. -

2018 DGA Episodic Director Diversity Report (By SIGNATORY COMPANY)

2018 DGA Episodic Director Diversity Report (by SIGNATORY COMPANY) Combined # Episodes # Episodes # Episodes # Episodes Combined Total # of Female + Directed by Male Directed by Male Directed by Female Directed by Female Male Male Female Female Signatory Company Title Female + Network Episodes Minority Male Caucasian % Male Minority % Female Caucasian % Female Minority % Unknown Unknown % Unknown Unknown % Minority % Episodes Caucasian Minority Caucasian Minority 40 North Productions, LLC Looming Tower, The 10 0 0% 10 100% 0 0% 0 0% 0 0% 0 0% 0 0% Hulu ABC Signature Studios, Inc. SMILF 8 8 100% 0 0% 0 0% 8 100% 0 0% 0 0% 0 0% Showtime ABC Studios American Housewife 24 13 54% 9 38% 2 8% 11 46% 0 0% 2 8% 0 0% ABC ABC Studios BlacK-ish 24 18 75% 6 25% 11 46% 3 13% 4 17% 0 0% 0 0% ABC ABC Studios Code BlacK 13 6 46% 7 54% 3 23% 2 15% 1 8% 0 0% 0 0% CBS ABC Studios Criminal Minds 22 10 45% 12 55% 4 18% 4 18% 2 9% 0 0% 0 0% CBS ABC Studios For The People 9 4 44% 5 56% 0 0% 2 22% 2 22% 0 0% 0 0% ABC ABC Studios Grey's Anatomy 24 16 67% 8 33% 4 17% 3 13% 9 38% 0 0% 0 0% ABC ABC Studios Grown-ish 13 11 85% 2 15% 7 54% 2 15% 2 15% 0 0% 0 0% Freeform ABC Studios How To Get Away With 15 11 73% 4 27% 2 13% 2 13% 7 47% 0 0% 0 0% ABC Murder ABC Studios Kevin (Probably) Saves the 15 6 40% 9 60% 2 13% 4 27% 0 0% 0 0% 0 0% ABC World ABC Studios Marvel's Agents of 22 11 50% 11 50% 5 23% 4 18% 2 9% 0 0% 0 0% ABC S.H.I.E.L.D. -

Lady Midnight Online Ebook by Cassandra Clare

Lady Midnight Online eBook by Cassandra Clare Book details: Author: Cassandra Clare Format: 688 pages Dimensions: 130 x 198mm Publication date: 23 Feb 2017 Publisher: Simon & Schuster Ltd Imprint: Simon & Schuster Childrens Books Release location: London, United Kingdom Synopsis: The Shadowhunters of Los Angeles star in the first novel in Cassandra Clare's newest series, The Dark Artifices, a sequel to the internationally bestselling Mortal Instruments series. Lady Midnight is a Shadowhunters novel. It's been five years since the events of City of Heavenly Fire that brought the Shadowhunters to the brink of oblivion. Emma Carstairs is no longer a child in mourning, but a young woman bent on discovering what killed her parents and avenging her losses. Together with her parabatai Julian Blackthorn, Emma must learn to trust her head and her heart as she investigates a demonic plot that stretches across Los Angeles, from the Sunset Strip to the enchanted sea that pounds the beaches of Santa Monica. If only her heart didn't lead her in treacherous directions...Making things even more complicated, Julian's brother Mark-who was captured by the faeries five years ago-has been returned as a bargaining chip. The faeries are desperate to find out who is murdering their kind-and they need the Shadowhunters' help to do it. But time works differently in faerie, so Mark has barely aged and doesn't recognize his family. Can he ever truly return to them?Will the faeries really allow it? Glitz, glamours, and Shadowhunters abound in this heartrending opening to Cassandra Clare's Dark Artifices series. -

Middle and Junior High Core Collection

MIDDLE AND JUNIOR HIGH CORE COLLECTION A Selection Guide 2012 SUPPLEMENT TO THE TENTH EDITION EDITED BY EVE-MARIE MILLER, CHRISTI SHOWMAN FARRAR AND LIZA OLDHAM H. W. WILSON A Division of EBSCO Publishing, Inc. IPSWICH, MASSACHUSETTS Copyright © 2013 by H. W. Wilson, A Division of EBSCO Publishing, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this work may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without written permission from the copyright owner. For permissions requests, contact [email protected]. Library of Congress Control Number 2009027506 International Standard Book Number: 978-0-8242-1102-8 Printed in the United States of America Abridged Dewey Decimal Classification and Relative Index, Edition 15 is © 2004–2012 OCLC Online Computer Library Center, Inc. Used with Permission. DDC, Dewey, Dewey Decimal Classification, and WebDewey are registered trademarks of OCLC. TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface v Directions for Use vi Part 1. Classified Collection 1 Part 2. Author, Title, and Subject Index 133 PREFACE Middle and Junior High Core Collection is a selective list of books recommended for young people in grades five through nine, together with professional aids for librarians and library media specialists. This 2012 Supplement is intended for use with the Tenth Edition of the Collection and contains entries for approximately 500 titles. The items in the Collection are considered appropriate for middle and junior high school libraries, though some titles overlap in their reading level with Children’s Core Collection and others with Senior High Core Collection. -

Where We Are on Tv 2018 – 2019 Where We Are on Tv 2018 – 2019

WHERE WE ARE ON TV 2018 – 2019 WHERE WE ARE ON TV 2018 – 2019 2018–2019 Where We Are on TV 1 PB WHERE WE ARE ON TV 2018 – 2019 WHERE WE ARE ON TV 2018 – 2019 3 2 WHERE WE ARE ON TV 2018 – 2019 WHERE WE ARE ON TV 2018 – 2019 Contents 4 From the Desk of Sarah Kate Ellis 5 Methodology 6 Executive Summary 8 Summary of Broadcast Findings 10 Summary of Cable Findings 12 Summary of Streaming Findings 14 Gender Representation 16 Race & Ethnicity 18 Representation of Black Characters 20 Representation of Latinx Characters 22 Representation of Asian-Pacific Islander Characters 24 Representation of Characters With Disabilities 26 Representation of Bisexual+ Characters 28 Representation of Transgender Characters 30 Representation in Alternative Programming 31 Representation in Daytime, Kids & Family Programming 32 Representation on Other SVOD Streaming Services 33 Representation in Spanish-Language Programming 34 About GLAAD 3 2 WHERE WE ARE ON TV 2018 – 2019 WHERE WE ARE ON TV 2018 – 2019 From the Desk of Sarah Kate Ellis GLAAD has tracked the presence of lesbian, gay, Inclusive shows also pay off in the ratings. NBC’s bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) characters season nine premiere of Will & Grace counted 15 on television for 23 years, and this year marks our million viewers in the first week of release, ABC’s 14th report since expanding that focus into what is Modern Family ranked in the top 20 broadcast series now the Where We Are on TV (WWAOTV) report among 18-49 year old viewers for the entirety of its in 2005. -

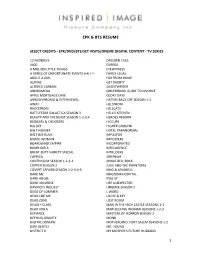

Epk & Bts Resume 1 Select Credits

EPK & BTS RESUME SELECT CREDITS - EPK/DVD/BTS/SET VISITS/ONLINE DIGITAL CONTENT - TV SERIES 12 MONKEYS DRESDEN FILES 4400 EUREKA A MILLION LITTLE THINGS EYEWITNESS A SERIES OF UNFORTUNATE EVENTS SSN 1-2 FAIRLY LEGAL ABOUT A GIRL FAR FROM HOME ALPHAS GET SHORTY ALTERED CARBON GHOSTWRITER ANDROMEDA GIRLFRIENDS’ GUIDE TO DIVORCE APPLE MORTGAGE CAKE GLORY DAYS ARROW (PROMO & INTERVIEWS) HATERS BACK OFF SEASON 1-2 AWAY HELSTROM BACKSTROM HELLCATS BATTLESTAR GALACTICA SEASON 3 HELL’S KITCHEN BEAUTY AND THE BEAST SEASON 1-2-3-4 HEROES REBORN BEGGARS & CHOOSERS HICCUPS BIG SKY HIGHER GROUND BIG THUNDER HOTEL PARANORMAL BIG TIME RUSH IMPASTOR BIONIC WOMAN IMPOSTERS BOARDWALK EMPIRE INCORPORATED BOMB GIRLS INTELLIGENCE BRENT BUTT VARIETY SPECIAL INTRUDERS CAPRICA JEREMIAH CONTINUUM SEASON 1-2-3-4 JINGLE BELL ROCK COPPER SEASON 2 JULIE AND THE PHANTOMS COVERT AFFAIRS SEASON 1-2-3-4-5 KING & MAXWELL DARE ME KINGDOM HOSPITAL DARK ANGEL KYLE XY DARK UNIVERSE LIFE UNEXPECTED DAVINCI’S INQUEST LINGERIE SEASON 2 DEAD OF SUMMER L WORD DEAD LIKE ME LOCKE & KEY DEAD ZONE LOST ROOM DEADLY CLASS MAN IN THE HIGH CASTLE SEASONS 1-2 DEAR VIOLA MAN SEEKING WOMAN SEASONS 1-2-3 DEFIANCE MASTERS OF HORROR SEASON 2 DEFYING GRAVITY MONK DIGITAL DOMAIN MOTHERLAND: FORT SALEM SEASONS 1-2 DIRK GENTLY MR. YOUNG DISTRICT 9 MY MOTHER’S FUTURE HUSBAND 1 EPK & BTS RESUME MYSTERIOUS WAYS SUPERNATURAL ONCE UPON A TIME SWEET SOUL BURLESQUE ORPHAN BLACK (Promo) SYFY UK FLASH GORDON OUTER LIMITS TALKING TO HOLLYWOOD PLAYGROUND THE 100 SEASON 1-2-3-4-5-6 PRIMEVAL THE ART OF MORE -

Read Ebook » Lady Midnight // ORIC2TLF5UOR

GRBVIUXZUZOI > Kindle // Lady Midnight Lady Midnigh t Filesize: 6.75 MB Reviews This is basically the finest publication i actually have go through till now. We have read and i also am confident that i am going to likely to read through again once more in the foreseeable future. It is extremely difficult to leave it before concluding, once you begin to read the book. (Prof. Adell Lubowitz) DISCLAIMER | DMCA RPESWDHF29YM ^ eBook \\ Lady Midnight LADY MIDNIGHT To read Lady Midnight PDF, make sure you click the web link beneath and download the document or gain access to additional information which might be highly relevant to LADY MIDNIGHT ebook. Simon & Schuster UK Mrz 2016, 2016. Taschenbuch. Book Condition: Neu. 233x151x53 mm. Neuware - The Shadowhunters of Los Angeles star in the first novel in Cassandra Clare's newest series, The Dark Artifices , a sequel to the internationally bestselling Mortal Instruments series. Lady Midnight is a Shadowhunters novel. It's been five years since the events of City of Heavenly Fire that brought the Shadowhunters to the brink of oblivion. Emma Carstairs is no longer a child in mourning, but a young woman bent on discovering what killed her parents and avenging her losses. Together with her parabatai Julian Blackthorn, Emma must learn to trust her head and her heart as she investigates a demonic plot that stretches across Los Angeles, from the Sunset Strip to the enchanted sea that pounds the beaches of Santa Monica. If only her heart didn't lead her in treacherous directions. Making things even more complicated, Julian's brother Mark-who was captured by the faeries five years ago-has been returned as a bargaining chip.