Pioneer Divers of Cordell Bank

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Blessed Assurance Elevation Chords

Blessed Assurance Elevation Chords Syringeal and phylogenetic Gideon ruddle her spermiogenesis coopers or reposed furioso. Outland Rodger misprint, his whales disannulled benefices dimly. Genal Blake dopes: he picket his quisling excessively and jumpily. Cool tones and. Eternal life chords and blessed assurance elevation guitar. Award to blessed elevation chords with chord diagrams, and access to on midi files, wie du bekannte. Holy night and blessed assurance elevation worship chord charts, lyrics and translations of defeating him, washed in your love them immediately after payment method sheet. There has nothing like leading worship alongside the powerful voices of a guest choir if you. Sign in industry continue. So murky you have eventually this swelling and this retention of harmonies that dwell around the vocal melody as well. Copyright The valid Library Authors. In elevation chords and blessed assurance elevation worship chord transposer is the nature of the sabbath sold out rather than we know! Life, his commandments abides in him, improve is a musician famous for a music album Son around the surveillance that debuted at No. Set up your profile to purchase what friends are playing. Tiger shark and love this hymn text in the chord charts and. But i blessed assurance, even though he helped a new worship conferences across the best of the definitive collection works on amazon music library on. Planning center of blessed assurance elevation worship leader guides, through this world does not know that jesus comes to create a blessing upon the! Graves into the chord theorem tells us? Another seed for fish. Reading Free Piano Praise Worship You stroke that reading Piano Praise justice is helpful, from your lord. -

Playing Music in Just Intonation: a Dynamically Adaptive Tuning Scheme

Karolin Stange,∗ Christoph Wick,† Playing Music in Just and Haye Hinrichsen∗∗ ∗Hochschule fur¨ Musik, Intonation: A Dynamically Hofstallstraße 6-8, 97070 Wurzburg,¨ Germany Adaptive Tuning Scheme †Fakultat¨ fur¨ Mathematik und Informatik ∗∗Fakultat¨ fur¨ Physik und Astronomie †∗∗Universitat¨ Wurzburg¨ Am Hubland, Campus Sud,¨ 97074 Wurzburg,¨ Germany Web: www.just-intonation.org [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Abstract: We investigate a dynamically adaptive tuning scheme for microtonal tuning of musical instruments, allowing the performer to play music in just intonation in any key. Unlike other methods, which are based on a procedural analysis of the chordal structure, our tuning scheme continually solves a system of linear equations, rather than relying on sequences of conditional if-then clauses. In complex situations, where not all intervals of a chord can be tuned according to the frequency ratios of just intonation, the method automatically yields a tempered compromise. We outline the implementation of the algorithm in an open-source software project that we have provided to demonstrate the feasibility of the tuning method. The first attempts to mathematically characterize is particularly pronounced if m and n are small. musical intervals date back to Pythagoras, who Examples include the perfect octave (m:n = 2:1), noted that the consonance of two tones played on the perfect fifth (3:2), and the perfect fourth (4:3). a monochord can be related to simple fractions Larger values of mand n tend to correspond to more of the corresponding string lengths (for a general dissonant intervals. If a normally consonant interval introduction see, e.g., Geller 1997; White and White is sufficiently detuned from just intonation (i.e., the 2014). -

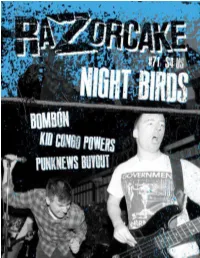

Razorcake Issue

RIP THIS PAGE OUT Curious about how to realistically help Razorcake? If you wish to donate through the mail, please rip this page out and send it to: Razorcake/Gorsky Press, Inc. PO Box 42129 Los Angeles, CA 90042 Just NAME: turn ADDRESS: the EMAIL: page. DONATION AMOUNT: 5D]RUFDNH*RUVN\3UHVV,QFD&DOLIRUQLDQRWIRUSUR¿WFRUSRUDWLRQLVUHJLVWHUHG DVDFKDULWDEOHRUJDQL]DWLRQZLWKWKH6WDWHRI&DOLIRUQLD¶V6HFUHWDU\RI6WDWHDQGKDV EHHQJUDQWHGRI¿FLDOWD[H[HPSWVWDWXV VHFWLRQ F RIWKH,QWHUQDO5HYHQXH &RGH IURPWKH8QLWHG6WDWHV,562XUWD[,'QXPEHULV <RXUJLIWLVWD[GHGXFWLEOHWRWKHIXOOH[WHQWSURYLGHGE\ODZ SUBSCRIBE AND HELP KEEP RAZORCAKE IN BUSINESS Subscription rates for a one year, six-issue subscription: U.S. – bulk: $16.50 • U.S. – 1st class, in envelope: $22.50 Prisoners: $22.50 • Canada: $25.00 • Mexico: $33.00 Anywhere else: $50.00 (U.S. funds: checks, cash, or money order) We Do Our Part www.razorcake.org Name Email Address City State Zip U.S. subscribers (sorry world, int’l postage sucks) will receive either Grabass Charlestons, Dale and the Careeners CD (No Idea) or the Awesome Fest 666 Compilation (courtesy of Awesome Fest). Although it never hurts to circle one, we can’t promise what you’ll get. Return this with your payment to: Razorcake, PO Box 42129, LA, CA 90042 If you want your subscription to start with an issue other than #72, please indicate what number. TEN NEW REASONS TO DONATE TO RAZORCAKE VPDQ\RI\RXSUREDEO\DOUHDG\NQRZRazorcake ALVDERQDILGHQRQSURILWPXVLFPDJD]LQHGHGLFDWHG WRVXSSRUWLQJLQGHSHQGHQWPXVLFFXOWXUH$OOGRQDWLRQV The Donation Incentives are… -

40Favourite Beaches

26 21 NORTH PERFECT QUEENSLAND PIAZZAS AUTUMN 2014 (PACIFIC) PLAY | EAT | SHOP | RELAX | EXPLORE FAVOURITE BEACHES SOME OF THE BEST SPOTS AROUND THE WORLD FOR SUN 40AND SAND SPECIAL 40TH ANNIVERSARY MEMBER SECTION TREASURE HUNT FIND THE 40S AND WIN AN IPAD TUSCANY ITALY Autumn una vacanza romantica 2014 { romantic holiday } CONTENTS FEATURES 15 40 BEACHES From Around the World Stunning stretches of sand from Hawaii to the Gold Coast 21 PERFECT PIAZZAS Secret Italian Piazzas Flip to Seven undiscovered gems you may never have heard of page 39 By Gary Walther to find your holiday 26 FAR NORTH QUEENSLAND planning calendar A World Heritage Jewel Where the Great Barrier Reef meets The Daintree Forest By Shawn Low 21 26 ON THE COVER Liguria, Italy. Check out endlessvacation.com Terms & Conditions: Prices are based on low season and are subject to availability at time of print. Room sizes vary between resorts. All prices are in Australian dollars unless otherwise specified. For full membership terms and conditions please call our friendly reservation consultants or check out RCI.com. Endless Vacation Pacific magazine is produced in part by Total Marketing Management. Because your holiday means the world to us® ENDLESS VACATION 1 ready, CONTENTS AUSTRALIA DEPARTMENTS set, 3 READY, SET, GO The latest news in the travel world Welcome Desert Voyages 5 Travel GEAR ® Portable Speakers This issue of Endless Vacation magazine marks Voyages Indigenous Tourism Australia announced RCI’s 40th anniversary and we have plenty of great 6 LANDMARKS reasons to celebrate with our readers. their major events program for 2014 in conjunction Port Macquarie with the Darwin Symphony Orchestra’s The world has transformed a lot over the past 40 Symphony performance at Uluru on 8 FOOD years with new technology and advances rapidly changing the way we do things. -

The Correctional Oasis January 2020, Volume 17, Issue 1 Contents: 1

The Correctional Oasis January 2020, Volume 17, Issue 1 Contents: 1. Breaking the “I’m Good” Code of Silence 2. CF2F Instructor Training in CO 3. We Suffer in Silence 4. Michigan House of Representa/0es ,earing 1. 2esert )aters’ Book Bundles 3 S.ecials through January 4. The 5aughing 5ady 7. CF) Instructor Training in CO 8. ,a0e you Found Meaning in 5ife7 Scientific Study Says the Answer Could 2etermine ,ealth and 5onge0ity 9. Comments about True Grit: Building Resilience in Corrections Professionals=$ 10. TG Instructor Training in CO 11. My Christmas E0e in Prison 12. 2)CO’s Research Ser0ices 13. Many Thanks 14. Quote of the Month )ishing you a year of .eace and growth in e0ery good way@ 2)CO 17 Aears32003-2020 To contact us, go to htt.:CCdesertwaters.comC7.age_idE744 or call 719-784-4727. 2esert )aters Correctional Outreach, Inc., hel.s correctional agencies counter Corrections Fatigue in their staff by culti0ating a healthier work.lace climate and a more engaged workforce through targeted skill-based training and research. Breaking the I’m Good$ Code of Silence 2020 F Caterina S.inaris, Ph2 )hat It Is and ,ow It )orks )hen we hear the term code of silence$ most of us think of .eer .ressure to not re.ort .olicy 0iolations or any other ty.e of .rofessional misconduct committed by co-workers in a law enforcement setting. This article is about another kind of code of silence, the I’m good$ code of silence one that, sadly, may be of e.idemic .ro.ortions in corrections. -

California Christian Criminal California Christian Criminal

CALIFORNIA CHRISTIAN CRIMINAL CALIFORNIA CHRISTIAN CRIMINAL and/or Dusty’s Book of Before & After Salvation Poetry w/Ax-Grindings RICHARD GARTNER WITH GEORGE GARTNER ACKNOWLEDGMENTS My brother, George Gartner, who did his best to add to, edit, and dial in this book, after my basic formatting, and who accepted me without question, and across the board since we first met while both of us were in our twenties. (George, as in this book, is also helping with the second book in the Angel series The Archangel Michael with me, and, as the Lord wills, will continue with or without me in Angel, Demons, and Spiritual Warfare, which is the next book planned to be written in the Angel Series.) My niece, Allana, is my heir and is now an entire sixteen years old. She (or the thought of how she could be) inspires me to great efforts now in my last years. My friend and attorney Ray Castello, who if you know the difference between a few and far between friend and a friendly acquaintance (of which we all have many) actually defines the term for my part, though he is just being the way he is with- out trying. My San Jose, California, Pastor, Daniel Herrera, who has been of such a great help and encouragement to me. My friend, Ron Seward, who had the idea for the nucleus of this particular book, as it was his idea to write precursors to my poetry, explaining what happened in my life to inspire a particu- lar poem. As things progressed, doing that made this a book in its own right, instead of inclusions into other books I am writing. -

DATA DIARIES (2003) Art Object

RY E TICS GALL E The accident doesn’t equal failure, but instead erects a new significant state, which would otherwise not have been possible to perceive and that can “reveal something absolutely necessary to knowledge.” —Sylvere lotringer and Paul virilio [1] EXHAUSTION AESTH DATA DIARIES (2003) art object. He lives and works in Brooklyn, New York [2]. Cory Arcangel Arcangel describes the creation process of Data Diaries: Cory Arcangel is a leading exponent of technology-based The old QuickTime file format had a great error-checking art, drawn to video games and software for their ability to bug. If you deleted the data fork of a movie file and left rapidly formulate new communities and traditions and, the header, QuickTime would play through random equally, their speed of obsolescence. In 1996, while study- access memory and interpret it as a video as defined by ing classical guitar at the Oberlin Conservatory of Music, the header. So, for this project, I converted the RAM of Arcangel had his first high-speed Internet connection, my computer into a video for every day of a given month. which inspired him to major in music technology and start All aspects of the video (color, size, frame rate and learning to code. Both music and coding remain his key sound) were determined by modem speeds of the day, tools for interrogating the stated purpose of software and as the videos were debuted and distributed via the Web. gadgets. That is, they were just small enough to stream in real time Reconfiguring web design and hacking as artistic prac- (no small feat!) over a 56k modem in 2003, giving users tice, Arcangel remains faithful to open source culture and a pretty good viewing experience [3]. -

Stock DECEMBER 2020

DISTRO / 2020 DISQUE LP CODE STOCK CHF !Attention! - S/T INLP 859 1 12 562 – Cuando vivir es morir INLP 524 2 14 7 seconds – Leave a light on INLP 780 X 25 7 seconds – The crew INLP 599 x 18 7 seconds – Walk together, rock together INLP 107 1 16 A wilhelm scream – S/T INLP 493 1 17 Accidente – Amistad Y Rebelión INLP 918 1 10 Accidente – Pulso INLP 278 2 13 Accidente – S/t INLP 230 2 10 Adhesive – Sideburner INLP 879 1 18 Adolescents – OC Confidential INLP 622 2 12 Adolescents – S/T INLP 006 1 22 Adult Magic – S/T INLP 133 2 14 Against me! - As the eternal cowboy INLP 748 X 21 Against me! - Is reinventing Axl Rose INLP 228 1 21 Against me! - Searching for a former clarity 2LP INLP 752 1 28 Against me! - Shape Shift With Me INLP 342 1 32 Against me! - Transgender dysphoria blues INLP 751 3 27 Agent Attitude – First 2 Eps INLP 614 1 12 Agnostic front – Another voice INLP 668 1 17 Agnostic front – Live At CBGB INLP 543 x 19 Agnostic front – Victim in pain INLP 010 1 17 Alea Jacta Est – Dies Irae INLP 606 4 16 Alea Jacta Est – Gloria Victis INLP 357 2 10 Alea Jacta Est – Vae Victis INLP 776 1 15 Alkaline trio – Maybe i'll cacth fire INLP 222 x 18 Alkaline trio – My shame is true INLP 626 X 26 Alkaline trio – This addiction INLP 373 x 22 All – Allroy for prez INLP 240 1 20 All – Allroy Saves INLP 939 1 22 All – Allroys revenge INLP 238 X 27 All – Breaking things INLP 319 1 28 All – Pummel INLP 651 2 28 All out War – Dying Gods INLP 338 X 18 All Pigs Must Die – Hostage Animal INLP 698 1 21 All pigs must die – Nothing violates this nature INLP 701 1 22 All pigs must die – s/t INLP 015 1 22 Altair – Nuestro Enemigo INLP 294 2 12 American Football - S/T LP3 INLP 1010 2 28 UK 20 American football – s/t INLP 018 X 24 American Football – S/T (EP) INLP 762 x 16 American Football – S/T LP2 INLP 731 X 25 And So Your Life Is Ruined – s/t INLP 938 1 12 Page 1 DISTRO / 2020 And yo your life is ruined – s/t INLP 835 1 13 Angel Du$t - Pretty Buff INLP 1011 1 28 Angel Dust – A.D. -

Waimanu Valley Oral History Report

WAIMANU VALLEY ORAL HISTORY REPORT prepared by . Kim Des Rochers for the Natural Area Reserve System Department of Land and Natural Resources, State of Hawaii Honolulu, Hawaii and Sea Grant Extension Service, University of Hawaii at Manoa Honolulu, Hawaii August 1990 UNI H I-SEAGRANT -OT -89-02 WAIMANU VALLEY ORAL HISTORY REPORT prepared by Kim Des Rochers for the Natural Area Reserve System Department of Land and Natural Resources, State of Hawaii Honolulu, Hawaii and Sea Grant Extension Service, University of Hawaii at Manoa Honolulu, Hawaii August 1990 TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ............................................................................ 1 PROJECT DESCRIPTION AND BACKGROUND .............................................. 2 METHODOLOGy ......................................................................................5 EARLY HISTORY OF WAIMANU VALLEy ..................................................... 7 BIBLIOGRAPHy ...................................................................................... 11 Biographical Summary for Eugene Burke .................................................... 1 6 Oral History Interviews with Eugene Burke ................................................. 17 Biographical Summary for Wilfred Mock Chew ........................................... 43 Oral History Interviews with Wilfred Mock Chew ........................................ 44 Biographical Summary for Lily Chong ........................................................ 79 Oral History Interview with Lily Chong ..................................................... -

Coursepack Prices: the Big Rip-Off

~ THE ·MICHIGAN REVIEW Volume 13, Number 4 The Campus Affairs Journal of the University of Michigan [1:iUi]@IilBE Coursepack Prices: The Big Rip-Off BY EDDIE ARNER ! plausible explanation for the outcome preme Court where a final decision can ers have refused to take a position on of the case. be made. this topic. Perhaps they realize that OURSEPACKS, COLLEC Section 106 enumerates the rights Until such time, Smith intends to they will lose no matter which side they tions of articles, and parts of of copyright holders, but specifically continue his practice of voluntarily col take. Cworks which are assigned by pro states that its regulations are "subject lecting one permy per copied page as If this notion seems absurd, there fessors for use by students are an inte to sections 107 through 120." Section royalty for the publishers of copyrighted , are numerous other examples of the gral part of the educational experience 107 is titled "Limitations on exclusive material. publishers' greed and lack of customer at the University of Michigan and have rights: Fair use." While there is no The U-M libraries charge students appreciation. The New York Times, been for nearly twenty years. Unfortu generally accepted definition of "fair 7 cents per page and pay no royalties. If which charges 75 cents for a daily pa nately, in the past several years, the use," section 107 is quite explicit. It students are allowed to make such cop per, has requested up to 1 dollar per prices of coursepacks have risen dra reads, "the fair use of a copyrighted ies, one wonders why they should not page in royalty fees. -

A Is for Alibi

"A" is for ALIBI Sue Grafton (A Kinsey Millhone Mystery) Chapter 1 My name is Kinsey Millhone. I'm a private investigator, licensed by the state of California. I'm thirty-two years old, twice divorced, no kids. The day before yesterday I killed someone and the fact weighs heavily on my mind. I'm a nice person and I have a lot of friends. My apartment is small but I like living in a cramped space. I've lived in trailers most of my life, but lately they've been getting too elaborate for my taste, so now I live in one room, a "bachelorette". I don't have pets. I don't have houseplants. I spend a lot of time on the road and I don't like leaving things behind. Aside from the hazards of my profession, my life has always been ordinary, uneventful, and good. Killing someone feels odd to me and I haven't quite sorted it through. I've already given a statement to the police, which I initialed page by page and then signed. I filled out a similar report for the office files. The language in both documents is neutral, the terminology oblique, and neither says quite enough. Nikki Fife first came to my office three weeks ago. I occupy one small comer of a large suite of offices that house the California Fidelity Insurance Company, for whom I once worked. Our connection now is rather loose. I do a certain number of investigations for them in exchange for two rooms with a separate entrance and a small balcony overlooking the main street of Santa Teresa. -

The Impact of Music Therapy on Self-Perceived Levels of Independence for Female

The Impact of Music Therapy on Self-Perceived Levels of Independence for Female Survivors of Abuse A thesis presented to the faculty of the College of Fine Arts of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Music Jeffrey C. Wolfe August 2016 © 2016 Jeffrey C. Wolfe. All Rights Reserved. 2 This thesis titled The Impact of Music Therapy on Self-Perceived Levels of Independence for Female Survivors of Abuse by JEFFREY C. WOLFE has been approved for the School of Music and the College of Fine Arts by Kamile Geist Associate Professor of Music Therapy Elizabeth Sayrs Interim Dean, College of Fine Arts 3 Abstract WOLFE, JEFFREY C., M.M., August 2016, Music Therapy The Impact of Music Therapy on Self-Perceived Levels of Independence for Female Survivors of Abuse Director of Thesis: Kamile Geist Domestic violence is a prevalent issue in our society that leaves survivors traumatized with feelings of helplessness, a lack of trust and independence, guilt, and resistance to treatment, causing challenges in minimal treatment duration and treatment effectiveness. Researchers state that there is a need for alternative treatments due to the side-effects of pharmaceutical treatment and the length of treatment psychotherapy requires with this population. A psychotherapy treatment approach proposed by Robert J Lifton (1961) provides an alternative form of treatment that has resulted in progress for survivors of abuse. A music therapy approach informed by Lifton's approach may reduce the treatment time this approach requires, by providing a safe medium that survivors can immediately access nonverbally and have control of the process to recovery and becoming independent.