Introduction to Astrophotography

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Noise and ISO CS 178, Spring 2014

Noise and ISO CS 178, Spring 2014 Marc Levoy Computer Science Department Stanford University Outline ✦ examples of camera sensor noise • don’t confuse it with JPEG compression artifacts ✦ probability, mean, variance, signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) ✦ laundry list of noise sources • photon shot noise, dark current, hot pixels, fixed pattern noise, read noise ✦ SNR (again), dynamic range (DR), bits per pixel ✦ ISO ✦ denoising • by aligning and averaging multiple shots • by image processing will be covered in a later lecture 2 © Marc Levoy Nokia N95 cell phone at dusk • 8×8 blocks are JPEG compression • unwanted sinusoidal patterns within each block are JPEG’s attempt to compress noisy pixels 3 © Marc Levoy Canon 5D II at dusk • ISO 6400 • f/4.0 • 1/13 sec • RAW w/o denoising 4 © Marc Levoy Canon 5D II at dusk • ISO 6400 • f/4.0 • 1/13 sec • RAW w/o denoising 5 © Marc Levoy Canon 5D II at dusk • ISO 6400 • f/4.0 • 1/13 sec 6 © Marc Levoy Photon shot noise ✦ the number of photons arriving during an exposure varies from exposure to exposure and from pixel to pixel, even if the scene is completely uniform ✦ this number is governed by the Poisson distribution 7 © Marc Levoy Poisson distribution ✦ expresses the probability that a certain number of events will occur during an interval of time ✦ applicable to events that occur • with a known average rate, and • independently of the time since the last event ✦ if on average λ events occur in an interval of time, the probability p that k events occur instead is λ ke−λ p(k;λ) = probability k! density function 8 © Marc Levoy Mean and variance ✦ the mean of a probability density function p(x) is µ = ∫ x p(x)dx ✦ the variance of a probability density function p(x) is σ 2 = ∫ (x − µ)2 p(x)dx ✦ the mean and variance of the Poisson distribution are µ = λ σ 2 = λ ✦ the standard deviation is σ = λ Deviation grows slower than the average. -

Digiscoping―Getting Close from Far Away from Photographing Nature in Alaska (2010) by Robert H

Digiscoping―Getting Close from Far Away from Photographing Nature in Alaska (2010) by Robert H. Armstrong Fujifilm FinePix 4700, Kowa scope with 20 power objective, f/2.8 at 1/74 second, ISO equivalent 200, minus 0.9 exposure compensation, from a calculated 231 feet away. Bald Eagle with young. This was one of my first experiences with digiscoping. I was quite pleased to be able to photograph the nest full-frame from so far away. I especially liked the scene of the parent taking a snooze with the very alert youngster nearby. 29 Digiscoping is taking pho- tos using a small digital camera mounted on a spotting scope. This setup can easily give you a lens equivalent of about 2,300 mm. That’s a very high magnification when you consider the biggest telephoto lenses for regular cameras are usually smaller than 1,000 mm and generally around 400 – 600 mm. Also, digiscoping equipment costs much less than high-quality large telephoto lenses and often weighs much less. Digiscoping allows you to photograph most wildlife from a considerable distance without disturbing them. From 40 feet away you can get close-up photos of songbirds. You can be more especially enjoy the way digiscoping Nikon Coolpix 995 digital camera. than 200 feet away for larger birds allows me to photograph birds (Some people seem to have trouble such as Great Blue Herons and at their nests without disturbing digiscoping with the newer model Bald Eagles. And you can be much them. 4500. I’m not sure why, but perhaps farther away for large mammals it is related to having a higher such as mountain goats and bears. -

Making Your Own Astronomical Camera by Susan Kern and Don Mccarthy

www.astrosociety.org/uitc No. 50 - Spring 2000 © 2000, Astronomical Society of the Pacific, 390 Ashton Avenue, San Francisco, CA 94112. Making Your Own Astronomical Camera by Susan Kern and Don McCarthy An Education in Optics Dissect & Modify the Camera Loading the Film Turning the Camera Skyward Tracking the Sky Astronomy Camp for All Ages For More Information People are fascinated by the night sky. By patiently watching, one can observe many astronomical and atmospheric phenomena, yet the permanent recording of such phenomena usually belongs to serious amateur astronomers using moderately expensive, 35-mm cameras and to scientists using modern telescopic equipment. At the University of Arizona's Astronomy Camps, we dissect, modify, and reload disposed "One- Time Use" cameras to allow students to study engineering principles and to photograph the night sky. Elementary school students from Silverwood School in Washington state work with their modified One-Time Use cameras during Astronomy Camp. Photo courtesy of the authors. Today's disposable cameras are a marvel of technology, wonderfully suited to a variety of educational activities. Discarded plastic cameras are free from camera stores. Students from junior high through graduate school can benefit from analyzing the cameras' optics, mechanisms, electronics, light sources, manufacturing techniques, and economics. Some of these educational features were recently described by Gene Byrd and Mark Graham in their article in the Physics Teacher, "Camera and Telescope Free-for-All!" (1999, vol. 37, p. 547). Here we elaborate on the cameras' optical properties and show how to modify and reload one for astrophotography. An Education in Optics The "One-Time Use" cameras contain at least six interesting optical components. -

AF-S TELECONVERTER TC-14E III 引火・爆発のおそれのある場所では使わない Nifi Cation by 1.4 ×

A 警告 English ■ Supplied Accessories Fixation du téléconvertisseur • AF-S VR Micro-Nikkor 105 mm f/2.8G IF-ED (no es compatible con autofoco)* • Não olhe para o sol através da lente ou do visor da câmera. A observação do 繁體中文 • Teleconverter Cap BF-3B • Soft Case CL-0715 Placez-vous à l’abri du soleil et mettez l’appareil photo hors tension. Alignez • AF-S VR Nikkor ED 200 mm F2G (IF) sol ou de outra fonte de luz intensa através da lente, do visor ou do 水につけたり、水をかけたり、雨にぬらさない J Thank you for your purchase of a Nikon teleconverter. Mounted between • Rear Lens Cap LF-4 le repère de montage du téléconvertisseur (e) sur le repère de montage • AF-S NIKKOR 200 mm f/2G ED VR II teleconversor pode causar incapacidade visual permanente. 感謝您購買尼康增距鏡。該鏡頭附件安裝於鏡頭和相機機身之間後, 水かけ禁止 感電や発火などの事故や故障の原因になります。 the lens and the camera body, this lens attachment increases lens mag- de l’objectif, situé sur l’appareil photo, puis posez le téléconvertisseur sur • AF-S VR Nikkor ED 300 mm F2.8G (IF) • Mantenha longe do alcance das crianças. A não observância desta precaução 可將鏡頭放大倍率增加至 1.4 倍。 在 使 用 本 產 品 前, 請 仔 細 閱 讀 這 些指南以及相機和鏡頭的說明書。 AF-S TELECONVERTER TC-14E III 引火・爆発のおそれのある場所では使わない nifi cation by 1.4 ×. Before using this product, please carefully read these ■ Specifi cations la monture d’objectif de l’appareil photo. En faisant attention de ne pas • AF-S NIKKOR 300 mm f/2.8G ED VR II poderá resultar em lesões. F プロパンガス、ガソリン、可燃性スプレーなどの引火性ガスや instructions together with the camera and lens manuals. -

Low-Cost Computational Astrophotography

Low-cost Computational Astrophotography Joseph Yen Peter Bryan Electrical Engineering Electrical Engineering Stanford University Stanford University [email protected] [email protected] Abstract 2. Related Work When taking photographs of the night sky, long ex- Currently, most astrophotographers compensate for posure times help photographers observe many stars, the rotation of the earth by physically moving the cam- but the rotation of the earth results in long star streak era along with the earth. However, some attempts arcs about the celestial pole. An algorithm for re- have been made to remove this requirement. To accu- moving these star streaks and substituting accurately rately localize stars in streaked images, one researcher placed point-like stars is designed and implemented. has re-mapped the star streak to polar coordinates, so Images containing star streaks are transformed into that all stars will have the same point-spread function. ones with un-streaked starry skies while retaining This technique was designed for locating specific stars color and brightness information. The procedure is for the purpose of identifying specific stars, but will shown to work consistently on a 35-image dataset. be applicable for our purposes when removing star streaks [4]. Other factors besides streaking can cause quality degradation in star images, and attempts have 1. Introduction been made to correct this. These have used such tech- niques as Richardson-Lucy deblurring [2] and maxi- Astrophotography is a widespread pastime in which mally sparse optimization [1]. DSLR cameras are used to take images of objects in space. Certain factors make this a very expen- sive hobby. -

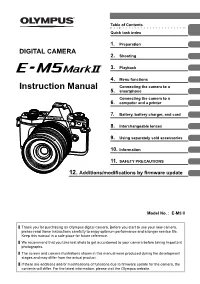

E-M5 Mark II (Ver2.0) Instruction Manual

Table of Contents Quick task index 1. Preparation DIGITAL CAMERA 2. Shooting 3. Playback 4. Menu functions Instruction Manual Connecting the camera to a 5. smartphone Connecting the camera to a 6. computer and a printer 7. Battery, battery charger, and card 8. Interchangeable lenses 9. Using separately sold accessories 10. Information 11. SAFETY PRECAUTIONS 12. Additions/modifications by firmware update Model No. : E-M5 II Thank you for purchasing an Olympus digital camera. Before you start to use your new camera, please read these instructions carefully to enjoy optimum performance and a longer service life. Keep this manual in a safe place for future reference. We recommend that you take test shots to get accustomed to your camera before taking important photographs. The screen and camera illustrations shown in this manual were produced during the development stages and may differ from the actual product. If there are additions and/or modifications of functions due to firmware update for the camera, the contents will differ. For the latest information, please visit the Olympus website. This notice concerns the supplied fl ash unit and is chiefl y directed to users in North America. Information for Your Safety IMPORTANT SAFETY INSTRUCTIONS When using your photographic equipment, basic safety precautions should always be followed, including the following: • Read and understand all instructions before using. • Close supervision is necessary when any fl ash is used by or near children. Do not leave fl ash unattended while in use. • Care must be taken as burns can occur from touching hot parts. • Do not operate if the fl ash has been dropped or damaged - until it has been examined by qualifi ed service personnel. -

DSLR Astrophotography They Say… Start with a Joke

DSLR Astrophotography They say… start with a joke. DLSR Wide-field Astrophotography The Advantages It’s Relatively Inexpensive All you need is a DLSR camera …and a tripod You Don’t Need This! Nikon v.s. Canon Most DSLR astrophotographers use Canon cameras. Canon releases the details of the camera’s software. This allows the development of third party software, designed specifically for astrophotography. Nikon does not create a truly raw image A simple median blurring filter is always applied... removing many stars, as they are seen as noise. This prohibits precise image calibration. Some Nikons allow the “Mode 3” work around. Using Nikon’s Mode 3 Simply start the bulb time exposure and terminate it by turning off the camera. The camera sees this as a low-power warning and immediately saves the image without running the median blurring filter Testing For Mode 3 Availability Take a one-minute dark exposure in Mode 1. This is a raw image with “no noise reduction” selected. Take a one-minute Mode 3 dark exposure. If Mode 3 is available, that exposure will have noticeably more hot pixels and noise. For Starters… Keep It Simple Set the focus to infinity... before it’s dark Mount the camera on a sturdy tripod Use a wide angle lens (18mm is nice) Set the lens to its lowest f-stop Use the RAW image format, at the highest ISO setting Shoot 20-30 second exposures Take about five dark exposures (more on this later) …and you can get an image like this! Nikon D40X 18mm @ f/4 ISO 1600 Mode 1 4 30-Sec exposures 4 30-Sec darks After taking several Milky Way shots it may be time to get more adventurous. -

A Guide to Smartphone Astrophotography National Aeronautics and Space Administration

National Aeronautics and Space Administration A Guide to Smartphone Astrophotography National Aeronautics and Space Administration A Guide to Smartphone Astrophotography A Guide to Smartphone Astrophotography Dr. Sten Odenwald NASA Space Science Education Consortium Goddard Space Flight Center Greenbelt, Maryland Cover designs and editing by Abbey Interrante Cover illustrations Front: Aurora (Elizabeth Macdonald), moon (Spencer Collins), star trails (Donald Noor), Orion nebula (Christian Harris), solar eclipse (Christopher Jones), Milky Way (Shun-Chia Yang), satellite streaks (Stanislav Kaniansky),sunspot (Michael Seeboerger-Weichselbaum),sun dogs (Billy Heather). Back: Milky Way (Gabriel Clark) Two front cover designs are provided with this book. To conserve toner, begin document printing with the second cover. This product is supported by NASA under cooperative agreement number NNH15ZDA004C. [1] Table of Contents Introduction.................................................................................................................................................... 5 How to use this book ..................................................................................................................................... 9 1.0 Light Pollution ....................................................................................................................................... 12 2.0 Cameras ................................................................................................................................................ -

2014 Orlando, FL

Engineering and Urology Society 29th Annual Meeting Saturday May 17th, 2014 Orlando, FL http://engineering-urology.org/ The Engineering and Urology Society offers a unique opportunity for collaboration where engineering innovation meets clinical demand. This leads to an unparalleled exchange of ideas and routes to address clinical problems with engineering solutions. The ultimate forum where these interchanges occur is at the Annual Meeting of the Engineering and Urology Society held in conjunction with the Annual American Urological Association Meeting. The EUS meeting is also the only dedicated section of the Endourology Society at the AUA. The Annual Meeting of the Engineering and Urology Society offers the delegates an opportunity to present and learn about the latest research developments in urologic technology. The morning session consists of state of the art lectures and discussions in cutting-edge areas of technology. The afternoon poster sessions and ever-growing subgroup meetings allow members to present their work, discuss, and obtain further feedback and ideas from fellow technophiles. This year’s 29th Annual Meeting will take place on May 17th, and has been organized by program chairmen Stavros Gravas, Bodo Knudsen, and M. Pilar Laguna. The morning sessions will begin with a thought- provoking discussion on the intersection of lab training and new imaging technology and urology. Following that, the spotlight is turned to advances in evidence making in uro-technology. Next, colleagues from the European Association of Urology (EAU), Uro-Technology section (ESUT) will present developments for new endoscopic instrumentation. After the lunch break, a brand-new session on “Innovations in Urology” will be held at the Science & Technology Hall, highlighting the grant and patent application processes which are an integral part of engineering and urology. -

The Archive of the Amateur Observation Network of the International Halley Watch Volume 2: Comet Halley

https://ntrs.nasa.gov/search.jsp?R=19970037542 2020-06-16T01:47:45+00:00Z JPL Publication 96-3, Vol. 2 The Archive of The Amateur Observation Network of The International Halley Watch Volume 2: Comet Halley Stephen J. Edberg Editor February 9, 1996 National Aeronautics and Space Administration Jet Propulsion Laboratory California Institute of Technology Pasadena, California The research described in this publication was done under the supervision of, and the publication was prepared by, the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology, under a contract with the National Aeronautics and Space Administration. Reference herein to any specific commercial product, process, or service by trade name, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise, does not constitute or imply its endorsement by the United States Government or the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology. ABSTRACT The International Halley Watch (IHW) was organized for the purpose of gathering and archiving the most complete record of the apparition of a comet, Halley's Comet (1982i = 1986 III = iP/Halley), ever compiled. The redirection of the International Sun-Earth Explorer 3 (ISEE-3) spacecraft, subsequently renamed the International Cometary Explorer (ICE), toward Comet Giacobini- Zinner (1984e = 1985 XIII = 21P/Giacobini-Zinner) prompted the initiation of a formal watch on that comet. All the data collected on P/Giacobini-Zinner and P/Halley have been published on CD-ROM in the Comet Halley Archive. This document contains a printed version of the archive data, collected by amateur astronomers, on these two comets. Volume 1 contains the Comet Giacobini-Zinner data archive and Volume 2 contains the Comet Halley archive. -

The Rise and Fall of Astrophotography Dr

Page2 GRIFFITH OBSERVER August The Rise and Fall of Astrophotography Dr. Joseph S.Tenn Department of Physics and Astronomy Sonoma State University Rohnert Park, California HONORABLE MENTION HUGHES GRIFFITH OBSERVER CONTEST 1987 Dr. Joe Tenn’s carefully crafted articles seem to be able to win a prize in the annual Hughes Aircraft Company Science Writing Contest any time he chooses to enter, and his students have occasionally won prizes, too. This heartens our outlook on higher education in America and provides interesting and unusual material for readers of this magazine. His last article, “Simon Newcomb, a Famous and Forgotten American Astronomer," appeared in the November, 1987, issue of the Griffith Observer, almost two years ago. It was saddled with several errors imposed by the editor, not the author, and we hope this time we have given Dr. Tenn’s most recent contribution more reliable preparation for print. His attention this time is fixed on the development of astrophotography. Onthe occasion of the January, 1987, American the first serious uses of chemical emulsions for Astronomical Society meeting in Pasadena, professional research. Less than fifty years earlier visiting astronomers were invited to tour the the first crude experiments suggested the Palomar Observatory. The five-meter telescope, possibility that astronomical information might be towering five stories above us, looked as imposing recorded photographically. as ever, although it had been in operation nearly four decades and was no longer the world's DaQUe"'9°iYPe$ largest. Astronomers were involved with photography The real surprise, to this visitor at least, was from its beginning. It was the French astronomer that the telescope is no longer used for photo- Francois Arago who made the first public graphy. -

Astrophotography Tales of Trial & Error

Astrophotography Tales of Trial & Error Dave & Marie Allen AVAC 13th April 2001 Contents Photos Through Camera Lens magnification Increasing 1 Star trails 2 Piggy back Photos Through the Telescope 3 Prime focus 4 Photo through the eyepiece 5 Eyepiece projection Camera Basics When the photograph is being exposed, Light directed to viewfinder the light is directed onto the film. The viewfinder is completely black. Usual photographic rules apply: Less light ! Longer exposures Higher f number ! Longer exposures Light directed to film Star Motion Stars rise and set – just like the Sun in the daytime. The motion of the stars can cause problems for astrophotography Star Motion Stars rise and set – just like the Sun in the daytime. The motion of the stars can cause problems for astrophotography Star Motion Stars rise and set – just like the Sun in the daytime. The motion of the stars can cause problems for astrophotography Star Motion Stars rise and set – just like the Sun in the daytime. The motion of the stars can cause problems for astrophotography Star Motion Stars rise and set – just like the Sun in the daytime. The motion of the stars can cause problems for astrophotography Tracking the motion of the stars during the exposure is called “guiding”. Requires a polar aligned mount and periodic corrections to keep the subject stationary relative to the camera. Done using slow motion controls – or more often with dual axis correctors. Guiding Photography Technique Guiding Required? Star trails No Piggy back Yes Prime focus Yes Photo through the