Cognitive Semiotics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Semiotics As a Cognitive Science

Elmar Holenstein Semiotics as a Cognitive Science The explanatory turn in the human sciences as well as research in "artifi- cial intelligence" have led to a little discussed revival of the classical Lockean sub-discipline of semiotics dealing with mental representations - aka "ideas" - under the heading of "cognitive science". Intelligent be- haviour is best explained by retuming to such obviously semiotic catego- ries as representation, gmbol, code, program, etc. and by investigations of the format of the mental representations. Pictorial and other "sub-linguisric" representations might be more appropriate than linguistic ones. CORRESPONDENCE: Elmar Holenstein. A-501,3-51-1 Nokendal, Kanazawa-ku Yoko- hama-shl, 236-0057, Japan. EMAIL [email protected] The intfa-semiotic cognitive tum Noam Chomsky's declaration that linguistics is a branch of psychology was understood by traditional linguists as an attack on the autonomous status of their science, a status which older structuralism endorsed by incorporating language (as a special sign system) into semiotics. Semiotics seemed to assure that genuinely linguistic relationships (grammatical and semantic relationships) were not rashly reduced to psychological or biological relationships (such as associations or adaptations). If it is looked at more closely in conjunction with the general development of the sciences in the 20th Century, the difference between Chomsky (1972: 28), who regards linguistics as a subfield of psychol- ogy, and Ferdinand de Saussure (1916: 33), for whom it is primarily a branch of "semiology", comes down to the fact that Saussure assigns linguistics in a descriptive perspective to universal semiotics, whereas Chomsky assigns it in an explanatory perspective to a special semiotics. -

Psych Homework

AP Notes – History and Approaches Early Theories – Where did we come from as a science??? In the beginning – people studied philosophy and physiology – both starting to study the human mind by the 1870s. 1879 - Wilhelm Wundt wanted to study human as a separate group not tied to the other two. In Germany he will establish the first lab to study human beings. This is the official start of psychology. Thus Wundt is the “Father of psychology” Wundt will study consciousness – the awareness of experiences Psychology grows – first 2 schools of thought Structuralism – will be started by Edward Titchner - he had studied under Wundt and then came to the US. Structuralism is based on the notion that we need to analyze consciousness in its basic elements to figure out why things are the way they are. (sensations, the components of vision, hearing, touch) o Introspection – careful, systematic self-observation of one’s own conscious experience. (with structuralism we would train people to analyze their thoughts and then exposed them to perceptual experiments (auditory tones, optical illusions, visual stimuli – then report) Functionalism – we should study the purpose of consciousness, why do we think the way we do, not some meaningless structure. We need to study how people adapt their behavior to their environment. William James will start this school of thought. William James also wrote the first textbook Gestalt – exact opposite of structuralism. We should study the whole not the parts to understand human behavior. (We will come back to this with perception) Max Wertheimer will start this school of thought. Other early view – These are still around Psychoanalysis – Freud – unconscious, repression, defense mechanisms Behaviorism – John B. -

Switching Gestalts on Gestalt Psychology: on the Relation Between Science and Philosophy

Switching Gestalts on Gestalt Psychology: On the Relation between Science and Philosophy Jordi Cat Indiana University The distinction between science and philosophy plays a central role in meth- odological, programmatic and institutional debates. Discussions of disciplin- ary identities typically focus on boundaries or else on genealogies, yielding models of demarcation and models of dynamics. Considerations of a disci- pline’s self-image, often based on history, often plays an important role in the values, projects and practices of its members. Recent focus on the dynamics of scientiªc change supplements Kuhnian neat model with a role for philoso- phy and yields a model of the evolution of philosophy of science. This view il- luminates important aspects of science and itself contributes to philosophy of science. This interactive model is general yet based on exclusive attention to physics. In this paper and two sequels, I focus on the human sciences and ar- gue that their role in the history of philosophy of science is just as important and it also involves a close involvement of the history of philosophy. The focus is on Gestalt psychology and it points to some lessons for philosophy of science. But, unlike the discussion of natural sciences, the discussion here brings out more complication than explication, and skews certain kinds of generaliza- tions. 1. How Do Science and Philosophy Relate to Each Other? a) As Nietzsche put it in the Genealogy of Morals: “Only that which has no history can be deªned.” This notion should make us wary of Heideggerian etymology, conceptual analysis and even Michael Friedman’s relativized, dialectical, post-Kuhnian Hegelianism alike. -

Giulio Cesare Procaccini (Bologna 1574 – Milan 1625)

THOS. AGNEW & SONS LTD. 6 ST. JAMES’S PLACE, LONDON, SW1A 1NP Tel: +44 (0)20 7491 9219. www.agnewsgallery.com Giulio Cesare Procaccini (Bologna 1574 – Milan 1625) The Adoration of the Magi Signed “G.C.P” (lower right) Oil on canvas 84 ¼ x 56 ¾ in. (214 x 144 cm.) Provenance Commissioned by Pedro de Toledo Osorio, 5th Marquis of Villafranca del Bierzo (Naples, 6 September 1546 – 17 July 1627), and by direct decent until 2017. This present painting by Giulio Cesare Procaccini, one of the most important painters in seventeenth-century Lombardy, is a significant rediscovery and a major addition to his oeuvre. Amidst a sumptuous architectural background, the Virgin sits at the centre of the scene, tenderly holding Jesus in her arms. She offers the Child’s foot to the oldest of the Magi, so that he can kiss it. The kings attributes of power, the crown and sceptre, lay in the foreground on the right, with his entire attention turned to worshiping the baby. Simultaneously, he offers Jesus a precious golden urn. Next to Mary are several figures attending the event. On the right, a dark- skinned king leans towards the centre of the composition holding an urn with incense. On the opposite side, the third king holds a box containing myrrh and looks upwards to the sky. Thos Agnew & Sons Ltd, registered in England No 00267436 at 21 Bunhill Row, London EC1Y 8LP VAT Registration No 911 4479 34 THOS. AGNEW & SONS LTD. 6 ST. JAMES’S PLACE, LONDON, SW1A 1NP Tel: +44 (0)20 7491 9219. -

Redalyc.Intersemiotic Translation from Rural/Biological to Urban

Razón y Palabra ISSN: 1605-4806 [email protected] Universidad de los Hemisferios Ecuador Sánchez Guevara, Graciela; Cortés Zorrilla, José Intersemiotic Translation from Rural/Biological to Urban/Sociocultural/Artistic; The Case of Maguey and Other Cacti as Public/Urban Decorative Plants.” Razón y Palabra, núm. 86, abril-junio, 2014 Universidad de los Hemisferios Quito, Ecuador Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=199530728032 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative RAZÓN Y PALABRA Primera Revista Electrónica en Iberoamerica Especializada en Comunicación. www.razonypalabra.org.mx Intersemiotic Translation from Rural/Biological to Urban/Sociocultural/Artistic; The Case of Maguey and Other Cacti as Public/Urban Decorative Plants.” Graciela Sánchez Guevara/ José Cortés Zorrilla.1 Abstract. This paper proposes, from a semiotic perspective on cognition and working towards a cognitive perspective on semiosis, an analysis of the inter-semiotic translation processes (Torop, 2002) surrounding the maguey and other cacti, ancestral plants that now decorate public spaces in Mexico City. The analysis involves three semiotics, Peircean semiotics, bio-semiotics, and cultural semiotics, and draws from other disciplines, such as Biology, Anthropology, and Sociology, in order to construct a dialogue on a trans- disciplinary continuum. The maguey and other cactus plants are resources that have a variety of uses in different spaces. In rural spaces, they are used for their fibers (as thread in gunny sacks, floor mats, and such), for their leaves (as roof tiles, as support beams, and in fences), for their spines (as nails and sewing needles), and their juice is drunk fresh (known as aguamiel or neutli), fermented (a ritual beverage known as pulque or octli), or distilled (to produce mescal, tequila, or bacanora). -

The Semiotic Hierarchy: Life, Consciousness, Signs and Language

10.3726/81608_169 Jordan Zlatev The Semiotic Hierarchy: Life, consciousness, signs and language This article outlines a general theory of meaning, The Semiotic Hierarchy, which distinguishes between four major levels in the organization of meaning: life, consciousness, sign function and language, where each of these, in this order, both rests on the previous level, and makes possible the at- tainment of the next. This is shown to be one possible instantiation of the Cognitive Semiotics program, with influences from phenomenology, Popper’s tripartite ontology, semiotics, linguistics, enactive cognitive sci- ence and evolutionary biology. Key concepts such as “language” and “sign” are defined, as well as the four levels of The Semiotic Hierarchy, on the basis of the type of (a) subject, (b) value-system and (c) world in which the subject is embedded. Finally, it is suggested how the levels can be united in an evolutionary framework, assuming a strong form of emergence giving rise to “ontologically” new properties: consciousness, signs and languages, on the basis of a semiotic, though not standardly biosemiotic, understanding of life. CORRESPONDENCE: Jordan Zlatev. Centre for Cognitive Semiotics, Centre for Lan- guages and Literature, Lund University, Sweden. EMAIL: [email protected] Introduction The goal of this article is to outline a general theory of meaning that I will refer to as The Semiotic Hierarchy. It distinguishes between four (macro) evolutionary levels in the organization of meaning: life, consciousness, sign function and language, where each of these, in this order, both rests on the previous level, and makes possible the attainment of the next. -

Issue 5 • Winter 2021 5 Winter 2021

Issue 5 • Winter 2021 5 winter 2021 Journal of the school of arts and humanities and the edith o'donnell institute of art history at the university of texas at dallas Athenaeum Review_Issue 5_FINAL_11.04.2020.indd 185 11/6/20 1:24 PM 2 Athenaeum Review_Issue 5_FINAL_11.04.2020.indd 2 11/6/20 1:23 PM 1 Athenaeum Review_Issue 5_FINAL_11.04.2020.indd 1 11/6/20 1:23 PM This issue of Athenaeum Review is made possible by a generous gift from Karen and Howard Weiner in memory of Richard R. Brettell. 2 Athenaeum Review_Issue 5_FINAL_11.04.2020.indd 2 11/6/20 1:23 PM Athenaeum Review Athenaeum Review publishes essays, reviews, Issue 5 and interviews by leading scholars in the arts and Winter 2021 humanities. Devoting serious critical attention to the arts in Dallas and Fort Worth, we also consider books and ideas of national and international significance. Editorial Board Nils Roemer, Interim Dean of the School of Athenaeum Review is a publication of the School of Arts Arts and Humanities, Director of the Ackerman and Humanities and the Edith O’Donnell Institute of Center for Holocaust Studies and Stan and Art History at the University of Texas at Dallas. Barbara Rabin Professor in Holocaust Studies School of Arts and Humanities Dennis M. Kratz, Senior Associate Provost, Founding The University of Texas at Dallas Director of the Center for Asian Studies, and Ignacy 800 West Campbell Rd. JO 31 and Celia Rockover Professor of the Humanities Richardson, TX 75080-3021 Michael Thomas, Director of the Edith O’Donnell Institute of Art History and Edith O’Donnell [email protected] Distinguished University Chair in Art History athenaeumreview.org Richard R. -

GIOTTO and MODERN ART* N OT Long Ago I Was Led to the Statement

GIOTTO AND MODERN ART* OT long ago I was led to the statement that we could N not understand modern art unless we understood Giotto-a statement that implied that the modern art move- ments have their sources in him. As a matter of fact, when we speak of the sources of any art movement, we are not on too solid ground. It is evident that there are powerfuI under- lying forces which influence and shape art forms, but to lo- cate the source of any style in a specific person means only to recognize the artistic criteria of the moment-standards which are as varied and changeable as that much desired quality which we caIl Beauty. Not too many years ago contemporary painting boasted free and virile brush strokes. This direct painting, then con- sidered the height of modernism, was shown as the direct descendant of Frans Hals and Velasquez. The imitative art of the 19th and 20th centuries looked for its sources in the illusionism of the Italian Renaissance and saw Masaccio as the father of modern painting. Then as subjective expression gradually replaced objective imitation, El Greco was rediscovered as the forefather of modern painting. With so many paternal ancestors already claimed, let us not fall into the error of putting still another father of modern art in the roots of the family tree. *This lecture was illustrated by lantern slides. In an attempt to clarify the allu- sions, the title and author of each illustration are printed in a marginal note at the point in the text that the illustration was used. -

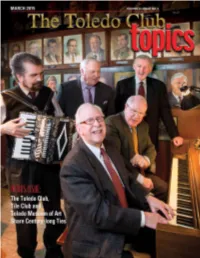

Manager's Message David Quinn SECRETARY Gregory H

BOARD OF DIRECTORS PRESIDENT LEGAL COUNSEL John Fedderke Justice G. Johnson, Jr VICE PRESIDENT DIRECTORS Aaron Swiggum Jackie Barnes TREASURER Richard Hylant Mike Marciniak Rebecca Shope Manager's Message David Quinn SECRETARY Gregory H. Wagoner Brett Seymour Roger Parker, General Manager TOLEDO CLUB STAFF 419-254-2988 • [email protected] ADMINISTRATION Roger Parker, General Manager 419-254-2988 Nathalie Helm, Executive Assistant 419-254-2980 FOOD & BEVERAGE SERVICE Nancy La Fountaine, Catering Manager 419-254-2981 Debra Rutkowski, Catering Assistant Manager 419-254-2981 Michael Rosendaul, Executive Chef 419-243-2200 ext. 2964 Charlotte Hall Concierge and Member Relations Manager 419-243-2200 ext. 2161 FACILITY Mark Hoffman, Director MARCH MADNESS 419-254-2997 MEMBERSHIP Russ Wozniak, Membership Director 419-254-2997 ACCOUNTING Joe Monks, Finance Director 419-254-2970 Paula Martin, Accounting Analyst 419-254-2996 ATHLETIC The winter months at the Club featured John Seidel, Director/Squash Pro 419-254-2962 a very active social and athletic calendar. Charissa Marconi, Fitness and Aquatics Director 419-254-2990 The member and guest participation levels were extraordinary. SECURITY David Rainey, Operations Manager The Winter Squash League and tournaments were at capacity. 419-254-2967 The Main Dining Room had many busy meal periods and all the EDITORIAL STAFF Editor in Chief: social events were nearly sold out. Shirley Levy – [email protected] Copy Editor: With the oncoming of spring, the transition month of March has several Art Bronson activities planned that will allow our members to enjoy their membership. Design/Art Direction: Tony Barone Design – 419-866-4826 The Main Dining Room will be featuring several unique dining experiences, [email protected] the Tavern will be following all the sports action including the Contributing Writers: Karen Klein, Cindy Niggemyer, Katherine Decker, NCAA Basketball tournament. -

Psychology Unit 1

PSYCHOLOGY Dr.K.Shanthi Assistant Professor & Head PG Department of Social Work Guru Nanak College (Autonomous) Unit 1 Syllabus: Definition of Psychology and its importance and role in social work practice. Scientific basis of psychology. Definition of behaviour. Psychology as a study of individual difference and observable behaviour. Brief history and Fields’ of Psychology. Psychology The word Psychology - derived from Greek literature 'Psyche‘ - 'soul' & 'Logos' - 'the study of': the study of the mind or soul the study of behavior. the systematic study of behavior and experience. is concerned with the experience and behaviour of the individual. Definition of Psychology Psychology is defined as the scientific study of human behaviour and mental processes. - Human behavior - observed directly. - Mental processes - thoughts, feelings, and motives that are not directly observable. Psychology its Importance and role in social work practice Psychology deals with human behaviour, emotions, projections, Cognition, learning and memory are core subject matters for psychology. interaction pattern between heredity and environment aware of individual differences in physical and mental traits and abilities. The theories - help to understand individuals’ behaviour. Psychology its Importance and role in social work practice to understand and analyse human behaviour. to bring about a change in personality through functioning or behaviour modification. In resolving problems related to adjustment. Social Case Work , dealing with individuals. -

Visual Semiotics: a Study of Images in Japanese Advertisements

VISUAL SEMIOTICS: A STUDY OF IMAGES IN JAPANESE ADVERTISEMENTS RUMIKO OYAMA THESIS SUBMIITED TO THE UNIVERSITY OF LONDON iN FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS OF THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY INSTITUTE OF EDUCATION UNIVERSITY OF LONDON NOVEMBER 1998 BIL LONDON U ABSTRACT 14 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 15 Chapter 1 INTRODUCTION 16 1.1 THE PURPOSE OF THE RESEARCH 16 1.2 DEVELOPMENT OF RESEARCH INTERESTS 16 1.3 LANGUAGE VERSUS VISUALS AS A SEMIOTIC MODE 20 1.4 THE ASPECT OF VISUAL SEMIOTICS TO BE FOCUSED ON: Lexis versus Syntax 23 1.5 CULTURAL VALUE SYSTEMS IN VISUAL SYNTAX: A challenge to the notion of universality 24 Chapter Ii THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK 26 2.1 INTRODUCTION 26 2.2 LITERATURE SURVEY ON STUDIES OF IMAGES 27 2.2.1 What is an image? 27 2.2.2 Art history/Art theories 29 2.2.3 Sociological approaches to visual images 36 2.2.4 Cultural approaches to visual images 44 2.2.4.1 Visual images as cultural products 45 2.2.4.2 Visual images from linguistic perspectives 50 2.2.5 Semiotic approaches to visual images 54 2.2.5.1 Saussure, Barthes (traditional semiology I semiotics) 54 2.2.5.2 Film semiotics 59 2 2.2.5.3 Social Semiotics 61 2.2.6 Reflection on the literature survey 66 2.3 A THEORY FOR A SEMIOTIC ANALYSIS OF THE VISUAL 71 2.3.1 Visual semiotics and the three metafunctions 72 2.3.1.1 The Ideational melafunction 73 2.3.1.2 The Textual metafunction 75 2.3.1.3 The Interpersonal metafunction 78 2.4 VERBAL TEXT IN VISUAL COMPOSITION: Critical Discourse Analysis 80 23 INTEGRATED APPROACH FOR A MULTI-MODAL ANALYSIS OF VISUAL AND VERBAL TEXTUAL OBJECTS -

THE BERNARD and MARY BERENSON COLLECTION of EUROPEAN PAINTINGS at I TATTI Carl Brandon Strehlke and Machtelt Brüggen Israëls

THE BERNARD AND MARY BERENSON COLLECTION OF EUROPEAN PAINTINGS AT I TATTI Carl Brandon Strehlke and Machtelt Brüggen Israëls GENERAL INDEX by Bonnie J. Blackburn Page numbers in italics indicate Albrighi, Luigi, 14, 34, 79, 143–44 Altichiero, 588 Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum catalogue entries. (Fig. 12.1) Alunno, Niccolò, 34, 59, 87–92, 618 Angelico (Fra), Virgin of Humility Alcanyiç, Miquel, and Starnina altarpiece for San Francesco, Cagli (no. SK-A-3011), 100 A Ascension (New York, (Milan, Brera, no. 504), 87, 91 Bellini, Giovanni, Virgin and Child Abbocatelli, Pentesilea di Guglielmo Metropolitan Museum altarpiece for San Nicolò, Foligno (nos. 3379 and A3287), 118 n. 4 degli, 574 of Art, no. 1876.10; New (Paris, Louvre, no. 53), 87 Bulgarini, Bartolomeo, Virgin of Abbott, Senda, 14, 43 nn. 17 and 41, 44 York, Hispanic Society of Annunciation for Confraternità Humility (no. A 4002), 193, 194 n. 60, 427, 674 n. 6 America, no. A2031), 527 dell’Annunziata, Perugia (Figs. 22.1, 22.2), 195–96 Abercorn, Duke of, 525 n. 3 Alessandro da Caravaggio, 203 (Perugia, Galleria Nazionale Cima da Conegliano (?), Virgin Aberdeen, Art Gallery Alesso di Benozzo and Gherardo dell’Umbria, no. 169), 92 and Child (no. SK–A 1219), Vecchietta, portable triptych del Fora Crucifixion (Claremont, Pomona 208 n. 14 (no. 4571), 607 Annunciation (App. 1), 536, 539 College Museum of Art, Giovanni di Paolo, Crucifixion Abraham, Bishop of Suzdal, 419 n. 2, 735 no. P 61.1.9), 92 n. 11 (no. SK-C-1596), 331 Accarigi family, 244 Alexander VI Borgia, Pope, 509, 576 Crucifixion (Foligno, Palazzo Gossaert, Jan, drawing of Hercules Acciaioli, Lorenzo, Bishop of Arezzo, Alexeivich, Alexei, Grand Duke of Arcivescovile), 90 Kills Eurythion (no.