Forest Insect and Disease Conditions in the Southwestern Region, 2018

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Blind/Visual Impairment Resources

ARIZONA Blind/Visual Impairment Resources Arizona Blind/Visual Impairment Resources Arizona Blind and Deaf Children's Foundation, Inc. 3957 East Speedway Blvd., Suite 207 Tucson, AZ 85712-4548 Phone: (520) 577-3700 E-mail: [email protected] Website: http://www.azblinddeafchildren.org/ Contact Name: Joseph Hayden, Chairman Organization Type: Independent and Community Living, State and Local Organizations Disabilities Served: Hearing Impairments / Deaf, Visual Impairment / Blind The Foundation’s mission is to invest in the future of Arizona’s children and youth with vision and hearing loss. Through fundraising, program development, advocacy and grant-making, the Foundation helps bridge the gap between public education funding and access to the quality educational experiences essential to prepare Arizona students to be self-sufficient and contributing members of society. They are an organization that supports the empowerment and achievements of blind and deaf children and youth through programs and initiatives. In partnership with public and private organizations, they develop and fund quality programs that target underserved children and youth. Arizona Center for the Blind and Visually Impaired, Inc. 3100 E. Roosevelt St. Phoenix, AZ 85008 Phone: (602) 273-7411 Fax: (602) 273-7410 E-mail: [email protected] Website: http://www.acbvi.org/ Contact Name: Jim LaMay, Executive Director Organization Type: Assistive Technology, Information Centers, State and Local Organizations Disabilities Served: Visual Impairment / Blind The mission of the Arizona Center for the Blind and Visually Impaired is to enhance the quality of life of people who are blind or otherwise visually impaired, by providing a wide range of services. These services promote independence, dignity, and full participation in all spheres of life, including at home, at work and in the community. -

Trip Planner

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Grand Canyon National Park Grand Canyon, Arizona Trip Planner Table of Contents WELCOME TO GRAND CANYON ................... 2 GENERAL INFORMATION ............................... 3 GETTING TO GRAND CANYON ...................... 4 WEATHER ........................................................ 5 SOUTH RIM ..................................................... 6 SOUTH RIM SERVICES AND FACILITIES ......... 7 NORTH RIM ..................................................... 8 NORTH RIM SERVICES AND FACILITIES ......... 9 TOURS AND TRIPS .......................................... 10 HIKING MAP ................................................... 12 DAY HIKING .................................................... 13 HIKING TIPS .................................................... 14 BACKPACKING ................................................ 15 GET INVOLVED ................................................ 17 OUTSIDE THE NATIONAL PARK ..................... 18 PARK PARTNERS ............................................. 19 Navigating Trip Planner This document uses links to ease navigation. A box around a word or website indicates a link. Welcome to Grand Canyon Welcome to Grand Canyon National Park! For many, a visit to Grand Canyon is a once in a lifetime opportunity and we hope you find the following pages useful for trip planning. Whether your first visit or your tenth, this planner can help you design the trip of your dreams. As we welcome over 6 million visitors a year to Grand Canyon, your -

GIS Handbook Appendices

Aerial Survey GIS Handbook Appendix D Revised 11/19/2007 Appendix D Cooperating Agency Codes The following table lists the aerial survey cooperating agencies and codes to be used in the agency1, agency2, agency3 fields of the flown/not flown coverages. The contents of this list is available in digital form (.dbf) at the following website: http://www.fs.fed.us/foresthealth/publications/id/id_guidelines.html 28 Aerial Survey GIS Handbook Appendix D Revised 11/19/2007 Code Agency Name AFC Alabama Forestry Commission ADNR Alaska Department of Natural Resources AZFH Arizona Forest Health Program, University of Arizona AZS Arizona State Land Department ARFC Arkansas Forestry Commission CDF California Department of Forestry CSFS Colorado State Forest Service CTAES Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Station DEDA Delaware Department of Agriculture FDOF Florida Division of Forestry FTA Fort Apache Indian Reservation GFC Georgia Forestry Commission HOA Hopi Indian Reservation IDL Idaho Department of Lands INDNR Indiana Department of Natural Resources IADNR Iowa Department of Natural Resources KDF Kentucky Division of Forestry LDAF Louisiana Department of Agriculture and Forestry MEFS Maine Forest Service MDDA Maryland Department of Agriculture MADCR Massachusetts Department of Conservation and Recreation MIDNR Michigan Department of Natural Resources MNDNR Minnesota Department of Natural Resources MFC Mississippi Forestry Commission MODC Missouri Department of Conservation NAO Navajo Area Indian Reservation NDCNR Nevada Department of Conservation -

Forest Insect and Disease Conditions in the Southwestern Region, 2008

United States Department of Forest Insect and Agriculture Forest Disease Conditions in Service Southwestern the Southwestern Region Forestry and Forest Health Region, 2008 July 2009 PR-R3-16-5 The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination in all its programs and activities on the basis of race, color, national origin, age, disability, and where applicable, sex, marital status, parental status, religion, sexual orientation, genetic information, political beliefs, reprisal, or because all or part of an individual’s income is derived from any public assistance program. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all programs.) Persons with disabilities who require alternative means for communication of program information (Braille, large print, audiotape, etc.) should contact USDA's TARGET Center at (202) 720- 2600 (voice and TTY). To file a complaint of discrimination, write to USDA, Director, Office of Civil Rights, 1400 Independence Avenue, SW, Washington, DC 20250-9410 or call (800) 795-3272 (voice) or (202) 720-6382 (TTY). USDA is an equal opportunity provider and employer. Cover photo: Pandora moth caterpillar collected on the North Kaibab Ranger District, Kaibab National Forest. Forest Insect and Disease Conditions in the Southwestern Region, 2008 Southwestern Region Forestry and Forest Health Regional Office Salomon Ramirez, Director Allen White, Pesticide Specialist Forest Health Zones Offices Arizona Zone John Anhold, Zone Leader Mary Lou Fairweather, Pathologist Roberta Fitzgibbon, Entomologist Joel McMillin, Entomologist -

Pine Shoot Insects Common in British Columbia

Environment Environnement 1+ Canada Canada Pine Shoot Insects Canadian Service Forestry canadien des Common in Serv~e forits British Columbia David Evans Pacific Forest Research Centre Victoria, British Columbia BC-X-233 PACIFIC FOREST RESEARCH CENTRE The Pacific Forest Research Centre (PFRC) is one of six regional research estab lishments of the Canadian Forestry Service of Environment Canada. The centre conducts a program of work directed toward the solution of major forestry problems and the development of more effective forest management techniques for use in British Columbia and the Yukon. The 30 research projects and over 150 studies which make up the research pro gram of PFRC are divided into three areas known as Forest Protection, Forest Environment and Forest Resources. These are supported by an Economics, Information and Administrative section and a number of specialized research support services such as analytical chemistry, computing microtechnique and remote sensing. Current research projecu, which focus on the establishment, growth and protection of the foresu, include: forest pathology problems, researd1 0f1 seed and cone insecU and disease, biological control of forest pesU, pest damage monitoring and assessment, seed and tree improvement, regenera tion and stand management. ISSN.()705·3274 Pine Shoot Insects Common in British Columbia David Evans Pacific Forest Research Centre 506 Wen Burnside Road. Victoria, British Columbia vaz 1M5 BC·X·233 1982 2 ABSTRACT RESUME This publication is an aid to the identification Ce document aidera a identifier les insectes of pine shoot insects on pines native to British Co des pousses du Pin sur les pins indigenes du Colombie lumbia. -

Arizona Regional Haze 308

Arizona State Implementation Plan Regional Haze Under Section 308 Of the Federal Regional Haze Rule Air Quality Division January 2011 (page intentionally blank) TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION........................................................................................................ 1 1.1 Overview of Visibility and Regional Haze..................................................................................2 1.2 Arizona Class I Areas.................................................................................................................. 3 1.3 Background of the Regional Haze Rule ......................................................................................3 1.3.1 The 1977 Clean Air Act Amendments................................................................................ 3 1.3.2 Phase I Visibility Rules – The Arizona Visibility Protection Plan ..................................... 4 1.3.3 The 1990 Clean Air Act Amendments................................................................................ 4 1.3.4 Submittal of Arizona 309 SIP............................................................................................. 6 1.4 Purpose of This Document .......................................................................................................... 9 1.4.1 Basic Plan Elements.......................................................................................................... 10 CHAPTER 2: ARIZONA REGIONAL HAZE SIP DEVELOPMENT PROCESS ......................... 15 2.1 Federal -

Geologic Influences on Apache Trout Habitat in the White Mountains of Arizona

GEOLOGIC INFLUENCES ON APACHE TROUT HABITAT IN THE WHITE MOUNTAINS OF ARIZONA JONATHAN W. LONG, ALVIN L. MEDINA, Rocky Mountain Research Station, U.S. Forest Service, 2500 S. Pine Knoll Dr, Flagstaff, AZ 86001; and AREGAI TECLE, Northern Arizona University, PO Box 15108, Flagstaff, AZ 86011 ABSTRACT Geologic variation has important influences on habitat quality for species of concern, but it can be difficult to evaluate due to subtle variations, complex terminology, and inadequate maps. To better understand habitat of the Apache trout (Onchorhynchus apache or O. gilae apache Miller), a threatened endemic species of the White Mountains of east- central Arizona, we reviewed existing geologic research to prepare composite geologic maps of the region at intermediate and fine scales. We projected these maps onto digital elevation models to visualize combinations of lithology and topog- raphy, or lithotopo types, in three-dimensions. Then we examined habitat studies of the Apache trout to evaluate how intermediate-scale geologic variation could influence habitat quality for the species. Analysis of data from six stream gages in the White Mountains indicates that base flows are sustained better in streams draining Mount Baldy. Felsic parent material and extensive epiclastic deposits account for greater abundance of gravels and boulders in Mount Baldy streams relative to those on adjacent mafic plateaus. Other important factors that are likely to differ between these lithotopo types include temperature, large woody debris, and water chemistry. Habitat analyses and conservation plans that do not account for geologic variation could mislead conservation efforts for the Apache trout by failing to recognize inherent differences in habitat quality and potential. -

2006 Tumamoc Hill Management Plan

TUMAMOC HILL CUL T URAL RESOURCES POLICY AND MANAGEMEN T PLAN September 2008 This project was financed in part by a grant from the Historic Preservation Heritage Fund which is funded by the Arizona Lottery and administered by the Arizona State Parks Board UNIVERSI T Y OF ARIZONA TUMAMOC HILL CUL T URAL RESOURCES POLICY AND MANAGEMEN T PLAN Project Team Project University of Arizona Campus & Facilities Planning David Duffy, AICP, Director, retired Ed Galda, AICP, Campus Planner John T. Fey, Associate Director Susan Bartlett, retired Arizona State Museum John Madsen, Associate Curator of Archaeology Nancy Pearson, Research Specialist Nancy Odegaard, Chair, Historic Preservation Committee Paul Fish, Curator of Archaeology Suzanne Fish, Curator of Archaeology Todd Pitezel, Archaeologist College of Architecture and Landscape Architecture Brooks Jeffery, Associate Dean and Coordinator of Preservation Studies Tumamoc Hill Lynda C. Klasky, College of Science U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service Western Archaeological and Conservation Center Jeffery Burton, Archaeologist Consultant Team Cultural Affairs Office, Tohono O’odham Nation Peter Steere Joseph Joaquin September 2008 UNIVERSI T Y OF ARIZONA TUMAMOC HILL CUL T URAL RESOURCES POLICY AND MANAGEMEN T PLAN Cultural Resources Department, Gila River Indian Community Barnaby V. Lewis Pima County Cultural Resources and Historic Preservation Office Linda Mayro Project Team Project Loy C. Neff Tumamoc Hill Advisory Group, 1982 Gayle Hartmann Contributing Authors Jeffery Burton John Madsen Nancy Pearson R. Emerson Howell Henry Wallace Paul R. Fish Suzanne K. Fish Mathew Pailes Jan Bowers Julio Betancourt September 2008 UNIVERSI T Y OF ARIZONA TUMAMOC HILL CUL T URAL RESOURCES POLICY AND MANAGEMEN T PLAN This project was financed in part by a grant from the Historic Preservation Heritage Fund, which is funded by the Arizona Lottery and administered by the Arizona State Acknowledgments Parks Board. -

Populus Tremula

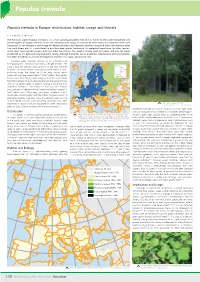

Populus tremula Populus tremula in Europe: distribution, habitat, usage and threats G. Caudullo, D. de Rigo The Eurasian aspen (Populus tremula L.) is a fast-growing broadleaf tree that is native to the cooler temperate and boreal regions of Europe and Asia. It has an extremely wide range, as a result of which there are numerous forms and subspecies. It can tolerate a wide range of habitat conditions and typically colonises disturbed areas (for example after fire, wind-throw, etc.). It is considered to be a keystone species because of its ecological importance for other species: it has more host-specific species than any other boreal tree. The wood is mainly used for veneer and pulp for paper production as it is light and not particularly strong, although it also has use as a biomass crop because of its fast growth. A number of hybrids have been developed to maximise its vigour and growth rate. Eurasian aspen (Populus tremula L.) is a medium-size, fast-growing tree, exceptionally reaching a height of 30 m1. The Frequency trunk is long and slender, rarely up to 1 m in diameter. The light < 25% branches are rather perpendicular, giving to the crown a conic- 25% - 50% 50% - 75% pyramidal shape. The leaves are 5-7 cm long, simple, round- > 75% ovate, with big wave-shaped teeth2, 3. They flutter in the slightest Chorology Native breeze, constantly moving and rustling, so that trees can often be heard but not seen. In spring the young leaves are coppery-brown and turn to golden yellow in autumn, making it attractive in all vegetative seasons1, 2. -

Of North Rim Pocket

Grand Canyon National Park National Park Service Grand Canyon Arizona U.S. Department of the Interior Pocket Map North Rim Services Guide Services, Facilities, and Viewpoints Inside the Park North Rim Visitor Center / Grand Canyon Lodge Campground / Backcountry Information Center Services and Facilities Outside the Park Protect the Park, Protect Yourself Information, lodging, restaurants, services, and Grand Canyon views Camping, fuel, services, and hiking information Lodging, camping, food, and services located north of the park on AZ 67 Use sunblock, stay hydrated, take Keep wildlife wild. Approaching your time, and rest to reduce and feeding wildlife is dangerous North Rim Visitor Center North Rim Campground Kaibab Lodge the risk of sunburn, dehydration, and illegal. Bison and deer can Park in the designated parking area and walk to the south end of the parking Operated by the National Park Service; $18–25 per night; no hookups; dump Located 18 miles (30 km) north of North Rim Visitor Center; open May 15 to nausea, shortness of breath, and become aggressive and will defend lot. Bring this Pocket Map and your questions. Features new interpretive station. Reservation only May 15 to October 15: 877-444-6777 or recreation. October 20; lodging and restaurant. 928-638-2389 or kaibablodge.com exhaustion. The North Rim's high their space. Keep a safe distance exhibits, park ranger programs, restroom, drinking water, self-pay fee station, gov. Reservation or first-come, first-served October 16–31 with limited elevation (8,000 ft / 2,438 m) and of at least 75 feet (23 m) from all nearby canyon views, and access to Bright Angel Point Trail. -

Poplars and Willows: Trees for Society and the Environment / Edited by J.G

Poplars and Willows Trees for Society and the Environment This volume is respectfully dedicated to the memory of Victor Steenackers. Vic, as he was known to his friends, was born in Weelde, Belgium, in 1928. His life was devoted to his family – his wife, Joanna, his 9 children and his 23 grandchildren. His career was devoted to the study and improve- ment of poplars, particularly through poplar breeding. As Director of the Poplar Research Institute at Geraardsbergen, Belgium, he pursued a lifelong scientific interest in poplars and encouraged others to share his passion. As a member of the Executive Committee of the International Poplar Commission for many years, and as its Chair from 1988 to 2000, he was a much-loved mentor and powerful advocate, spreading scientific knowledge of poplars and willows worldwide throughout the many member countries of the IPC. This book is in many ways part of the legacy of Vic Steenackers, many of its contributing authors having learned from his guidance and dedication. Vic Steenackers passed away at Aalst, Belgium, in August 2010, but his work is carried on by others, including mem- bers of his family. Poplars and Willows Trees for Society and the Environment Edited by J.G. Isebrands Environmental Forestry Consultants LLC, New London, Wisconsin, USA and J. Richardson Poplar Council of Canada, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada Published by The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations and CABI CABI is a trading name of CAB International CABI CABI Nosworthy Way 38 Chauncey Street Wallingford Suite 1002 Oxfordshire OX10 8DE Boston, MA 02111 UK USA Tel: +44 (0)1491 832111 Tel: +1 800 552 3083 (toll free) Fax: +44 (0)1491 833508 Tel: +1 (0)617 395 4051 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.cabi.org © FAO, 2014 FAO encourages the use, reproduction and dissemination of material in this information product. -

Arizona Relocation Guide

ARIZONA RELOCATION GUIDE WELCOME TO THE VALLEY OF THE SUN Landmark Title is proud to present the greatest selection of golf courses. As the following relocation guide! If you are cultural hub of the Southwest, Phoenix is thinking of moving to the Valley of the also a leader in the business world. Sun, the following will help you kick The cost of living compared with high start your move to the wonderful quality of life is favorable com- greater Phoenix area. pared to other national cities. FUN FACT: Arizona is a popular destination and is We hope you experience and growing every year. There are plenty of enjoy everything this state that Arizona’s flag features a copper-colored activities to partake in, which is easy to we call home, has to offer. star, acknowledging the state’s leading do with 300+ days of sunshine! role in cooper when it produced 60% of the total for the United States. There is something for everyone; the outdoor enthusiast, recreational activities, hospitality, dining and shopping, not to mention the nation’s 3 HISTORY OF THE VALLEY Once known as the Arizona Territory, built homes in, what was known as, By the time the United States entered WW the Valley of the Sun contained one Pumkinville where Swilling had planted II, one of the 7 natural wonders of the of the main routes to the gold fields in the gourds along the canal banks. Duppa world, the Grand Canyon, had become California. Although gold and silver were presented the name of Phoenix as related a national park, Route 66 was competed discovered in some Arizona rivers and to the story of the rebirth of the mythical and Pluto had been discovered at the mountains during the 1860’s, copper bird born from the ashes.