A Microhistory of the Chicago Neo-Futurists

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

This Is Chicago

“You have the right to A global city. do things in Chicago. A world-class university. If you want to start The University of Chicago and its a business, a theater, namesake city are intrinsically linked. In the 1890s, the world’s fair brought millions a newspaper, you can of international visitors to the doorstep of find the space, the our brand new university. The landmark event celebrated diverse perspectives, backing, the audience.” curiosity, and innovation—values advanced Bernie Sahlins, AB’43, by UChicago ever since. co-founder of Today Chicago is a center of global The Second City cultures, worldwide organizations, international commerce, and fine arts. Like UChicago, it’s an intellectual destination, drawing top scholars, companies, entrepre- neurs, and artists who enhance the academic experience of our students. Chicago is our classroom, our gallery, and our home. Welcome to Chicago. Chicago is the sum of its many great parts: 77 community areas and more than 100 neighborhoods. Each block is made up CHicaGO of distinct personalities, local flavors, and vibrant cultures. Woven together by an MOSAIC OF extensive public transportation system, all of Chicago’s wonders are easily accessible PROMONTORY POINT NEIGHBORHOODS to UChicago students. LAKEFRONT HYDE PARK E JACKSON PARK MUSEUM CAMPUS N S BRONZEVILLE OAK STREET BEACH W WASHINGTON PARK WOODLAWN THEATRE DISTRICT MAGNIFICENT MILE CHINATOWN BRIDGEPORT LAKEVIEW LINCOLN PARK HISTORIC STOCKYARDS GREEK TOWN PILSEN WRIGLEYVILLE UKRAINIAN VILLAGE LOGAN SQUARE LITTLE VILLAGE MIDWAY AIRPORT O’HARE AIRPORT OAK PARK PICTURED Seven miles UChicago’s home on the South Where to Go UChicago Connections south of downtown Chicago, Side combines the best aspects n Bookstores: 57th Street, Powell’s, n Nearly 60 percent of Hyde Park features renowned architecture of a world-class city and a Seminary Co-op UChicago faculty and graduate alongside expansive vibrant college town. -

2018 Barndance Program.Indd

Celebrating 19 Years of Cancer Awareness PROCEEDS TO BENEFIT CANCER AWARENESS | EDUCATION TREATMENT | RESEARCH THE BEST 7 HOURS OF SUMMER LIVE AUCTION ITEMS 1. White Sox Diamond Skybox for 20 Chicago White Sox vs. Cleveland Indians | Sunday, August 12 | 1:10pm • Luxury Diamond Suite for 20 at Guaranteed Rate Field • Food and beverages included: buffalo chicken wings, roast beef & turkey sandwiches, Caesar salad, hot dogs, peanuts and fresh fruit, along with 3 cases of beer and soda to enjoy during the game. • 2 parking passes. Thank you to 3 Brothers Restaurant, Murphy’s Flooring, Consolidated Electric Distributors (CED) and World Security & Control for underwriting this package. 2. They Always Go in 3’s | Final Tours of Music Icons Package Lynyrd Skynyrd - Friday, August 3 | Joan Baez - Friday, October 5 Elton John - Saturday, October 27 • 4 tickets to Lynyrd Skynrd | Last of the Street Survivors Farewell Tour on Friday, August 3 at Hollywood Casino Amphitheatre in Tinley Park, IL at 6:00 pm. End seats in section 100 with special guests: The Marshall Tucker Band, .38 Special and Jamey Johnson. • 2 rooms at the Fairfield Inn & Suites Chicago Tinley Park. • Bonus item for this package: a sealed original first LP Lynyrd Skynrd record from 1973 containing many of their iconic hits. Plus, a Marshal Tucker and .38 special albums. • 2 tickets to Joan Baez | Fare Thee Well…Tour 2018 at the beautiful Chicago Theater on Friday, October 5 at 8:00 pm. Tickets on the main floor, front row AA behind pit seating, end seats 401 & 403. • A $250 Visa card to use to book your overnight stay at the Chicago Theatre. -

Summer 2019 Calendar of Events

summer 2019 Calendar of events Hans Christian Andersen Music and lyrics by Frank Loesser Book and additional lyrics by Timothy Allen McDonald Directed by Rives Collins In this issue July 13–28 Ethel M. Barber Theater 2 The next big things Machinal by Sophie Treadwell 14 Student comedians keep ’em laughing Directed by Joanie Schultz 20 Comedy in the curriculum October 25–November 10 Josephine Louis Theater 24 Our community 28 Faculty focus Fun Home Book and lyrics by Lisa Kron 32 Alumni achievements Music by Jeanine Tesori Directed by Roger Ellis 36 In memory November 8–24 37 Communicating gratitude Ethel M. Barber Theater Julius Caesar by William Shakespeare Directed by Danielle Roos January 31–February 9 Josephine Louis Theater Information and tickets at communication.northwestern.edu/wirtz The Waa-Mu Show is vying for global design domination. The set design for the 88th annual production, For the Record, called for a massive 11-foot-diameter rotating globe suspended above the stage and wrapped in the masthead of the show’s fictional newspaper, the Chicago Offering. Northwestern’s set, scenery, and paint shops are located in the Virginia Wadsworth Wirtz Center for the Performing Arts, but Waa-Mu is performed in Cahn Auditorium. How to pull off such a planetary transplant? By deflating Earth. The globe began as a plain white (albeit custom-built) inflatable balloon, but after its initial multisection muslin wrap was created (to determine shrinkage), it was deflated, rigged, reinflated, motorized, map-designed, taped for a paint mask, primed, painted, and unpeeled to reveal computer-generated, to-scale continents. -

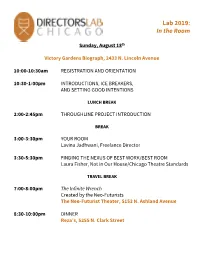

Lab 2019: in the Room

Lab 2019: In the Room Sunday, August 18th Victory Gardens Biograph, 2433 N. Lincoln Avenue 10:00-10:30am REGISTRATION AND ORIENTATION 10:30-1:00pm INTRODUCTIONS, ICE BREAKERS, AND SETTING GOOD INTENTIONS LUNCH BREAK 2:00-2:45pm THROUGHLINE PROJECT INTRODUCTION BREAK 3:00-3:30pm YOUR ROOM Lavina Jadhwani, Freelance Director 3:30-5:30pm FINDING THE NEXUS OF BEST WORK/BEST ROOM Laura Fisher, Not in Our House/Chicago Theatre Standards TRAVEL BREAK 7:00-8:00pm The Infinite Wrench Created by the Neo-Futurists The Neo-Futurist Theater, 5153 N. Ashland Avenue 8:30-10:00pm DINNER Reza’s, 5255 N. Clark Street Lab 2019: In the Room Monday, August 19th The Design Museum of Chicago, 72 E. Randolph Street 10:00-10:30am CHECK-IN AND QUESTIONS 10:30-11:45am SETTING THE STAGE Hallie Rosen, Chicago Architecture Center BREAK 12:00-1:00pm DOWNTOWN THEATRE HISTORY Melanie Wang, Dept. of Cultural Affairs and Special Events Mitchell J. Ward, Free Tours by Foot LUNCH AND TRAVEL BREAK/OPTIONAL CONTINUED TOUR The Second City, 230 W. North Avenue 2:00-5:00pm SATIRE AND THE SECOND CITY Rachael Mason, The Second City BREAK 5:00-6:00pm COMEDY TODAY & THE MAINSTAGE PROCESS Anthony LeBlanc, Jesse Swanson, Mick Napier, and others TBD, The Second City FREE NIGHT Lab 2019: In the Room Tuesday, August 20th Reva and David Logan Center for the Arts, 915 E. 60th Street 10:00-10:15am CHECK-IN AND QUESTIONS 10:15-11:15am THE BEND IN THE ROAD Lydia Milman-Schmidt, Parent-Artist Advocacy League Cassie Calderone, Love, Your Doula BREAK 11:30-12:30pm DIRECTING VIRTUALLY Alice Bever, Chang Nai Wen, Monty Cole, and Evan Tsitias, Freelance Directors and International Lab Affiliates LUNCH BREAK 1:30-2:30pm ROOM FOR ART IN ACADEMIA Tiffany Trent, Logan Center for the Arts BREAK 3:00-5:00pm CREATING A TRANS AFFIRMING WORKPLACE Carolyn Leach, Chicago House TransWorks 5:00-6:00pm PEER-LED SESSION TRAVEL AND DINNER BREAK 8:00pm THE BEST OF SECOND CITY Directed by Jonald Reyes UP Comedy Club, 230 W. -

Group Outings & Events

Group Outings & Events GROUP PERKS & BENEFITS DINNER PACKAGES COCKTAIL RECEPTIONS PRIVATE EVENTS FUNDRAISERS VENUE RENTALS TESTIMONIALS CATERING Group Perks & Benefits LAUGH OUT LOUD ENTERTAINMENT For more than half a century, The Second City has been daring audiences to laugh at our world, our shared troubles, and ourselves. Bring your group to enjoy the latest performance of cutting edge sketch comedy combined with songs & improv, that’s sure to keep them laughing for weeks to come! GROUP BENEFITS: The Second City Toronto Theatre can accommodate groups of up to 300 guests. When booking your group of 15 or more, you can expect: • Highest Quality Customer Service • Lunch/Dinner Package Options • No Service Fees • Private Reception Options • Flexible Deposit Policy • Group tickets starting at $12 • Group Seating DINNER PACKAGES. COCKTAIL RECEPTIONS. 416.343.0033 EXT. 201 PRIVATE EVENTS. FUNDRAISERS. [email protected] VENUE RENTALS. CATERING. TESTIMONIALS. SECONDCITY.COM/PRIVATE-EVENTS INQUIRE NOW. Group Dinner Packages START THE NIGHT OUT RIGHT Bring your group to enjoy the latest performance of cutting edge sketch comedy combined with songs & improv that’s sure to keep them laughing for weeks to come! The Second City offers pre-show dinner options to a number of restaurant partners in the neighbourhood, sure to suit any group’s tastes or budget. Wayne Gretzky’s Restaurant is The Second City’s main restaurant partner, and offers unique access to the theatre. Showtime Show Only With Dinner Menu A Menu B Menu C Mon 8PM $12 $43 $50 $55 Tues - Thurs 8PM $22 $53 $60 $65 Fri 7:30 & 10PM $26 $57 $64 $69 Sat 7:30 & 10PM $32 $63 $70 $75 Sun 7:30PM $22 $53 $60 $65 **Prices listed are for groups of 15 or more and are subject to additional taxes and gratuities. -

Chicago's Legendary Improv Theater Troupe the Second City Returns to the Kimmel Center Cultural Campus for Look Both Ways

Tweet It! .@TheSecondCity returns to the @KimmelCenter 1/19 & 1/20 for a weekend full of sketch, songs & satire! More info @ kimmelcenter.org Press Contact: Monica Robinson Rachel Goldman 215-790-5847 267-765-3712 [email protected] [email protected] CHICAGO’S LEGENDARY IMPROV THEATER TROUPE THE SECOND CITY RETURNS TO THE KIMMEL CENTER CULTURAL CAMPUS FOR LOOK BOTH WAYS BEFORE TALKING, JANUARY 19 & 20, 2018 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE (Philadelphia, PA, November 27, 2017) –– Edgy, thought-provoking and always spectacularly funny, The Second City improv troupe returns to the Kimmel Center’s Perelman Theater for performances on Friday, January 19, 2018 and Saturday, January 20, 2018. It’s been known for nearly six decades for producing cutting-edge satirical revues and launching the careers of generation after generation of comedy’s best and brightest. The Second City alumni include Tina Fey, Stephen Colbert, Steve Carell, Gilda Radner, Bill Murray, and more. Their new show, Look Both Ways Before Talking, will feature The Second City’s signature improv comedy, audience interaction, and original of-the-moment sketches and songs. “It is always a pleasure to welcome the return of The Second City to our Kimmel Center Cultural Campus,” said Anne Ewers, President & CEO of the Kimmel Center for the Performing Arts. “Not only do they present ever-changing, socially relevant material, but it is exciting to see what may well be the future leaders of the comedy world honing their craft on our stage!” The Second City opened its doors in December of 1959 and since then has become the world’s most influential and prolific comedy, theater, and improv school. -

Second City Center for Performing Arts

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Governors State University Governors State University OPUS Open Portal to University Scholarship Center for Performing Arts Memorabilia Center for Performing Arts 4-18-1998 Second City Center for Performing Arts Follow this and additional works at: http://opus.govst.edu/cpa_memorabilia Recommended Citation Center for Performing Arts, "Second City" (1998, 2001). Center for Performing Arts Memorabilia. Book 139. http://opus.govst.edu/ cpa_memorabilia/139 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Center for Performing Arts at OPUS Open Portal to University Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Center for Performing Arts Memorabilia by an authorized administrator of OPUS Open Portal to University Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. fOR PfftfORMIHO flRTS presents National Touring Company GOVERNORS STATE UNIVERSITY UNIVERSITY PARK, ILLINOIS THE CENTER FOR PERFORMING ARTS PRESENTS NATIONAL TOURING COMPANY Taking its name from the title of A.J. Liebling's derisive profile of Chicago in The New Yorker, The Second City opened on December 16, 1959. Success was almost instantaneous. Before the startled actors knew it, they were inundated with praise from the press, including Time Maga- zine, which called it "a temple of satire." The concept that is The Second City has always been translated by six or seven actors who enliven an empty stage with topical comedy sketches. Using few props and costumes, punctuating scenes with original music, the ensemble creates a slice-of-life environment, lampooning our modern lives, political, social, and cultural. -

Chicago Theatre Standards

Chicago Theatre Standards December 2017 This document is authored by representatives of Chicago theatre companies, artists, and administrators who volunteered their time, experience and expertise over the course of two years. It has been tested over the course of a year by 20 Chicago theatres and vetted by a variety of industry and legal professionals. A list of contributing institutions and individuals can be found at notinourhouse.org. Rev 12-11-17 1 Table of Contents Declaration of Purpose ................................................................................................................................................ 3 History ............................................................................................................................................................................................ 4 Mission Statement ...................................................................................................................................................................... 4 Who is the Chicago Theatre Standards for? ....................................................................................................................... 4 Disclaimer ..................................................................................................................................................................................... 5 How to Use This Document ......................................................................................................................................... 6 Definitions -

Showtime 2004

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Contact: Cathy Taylor, Cathy Taylor Public Relations (773) 564-9564; [email protected] Ben Thiem, Director of Member Services, League of Chicago Theatres (312) 554-9800; [email protected] SUMMER 2019 THEATER HIGHLIGHTS Chicago, IL – Celebrating 2019 as the Year of Chicago Theatre, Chicago will continue to produce some of the most exciting work in the country this summer. Offerings from the city’s more than 250 producing theaters feature everything from the latest musicals to highly anticipated world premieres. For a comprehensive list of Chicago productions including a Summer Theatre Guide, visit the League of Chicago website, ChicagoPlays.com. Half-price tickets are available at HotTix.org or at the two Hot Tix half- price ticket locations: across from the Chicago Cultural Center at Expo72 (72 E. Randolph) and Block Thirty Seven, Shops at 108 N. State. Hot Tix offers half-price tickets for the current week and some performances in advance. “As we approach the halfway point of the Year of Chicago Theatre, I encourage every Chicagoan and visitor to attend a production by one of our 250 theater companies. This summer, there is a wide range of offerings, including an impressive number of musicals and world premieres. Simply, there is something for everyone,” notes Deb Clapp, Executive Director of the League of Chicago Theatres. The following is a selection of notable work playing in Chicago throughout the summer: New works and adaptations include: Lookingglass Theatre presents a new adaptation of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein. Mary Shelley’s unsettling story crackles to life as Victor Frankenstein must contend with his unholy creation. -

The Second City Linking Laughter to Technology

Case Study The Second City Linking Laughter to Technology The Company Industry Comedy is serious business. The Second City, referred to by the New York Times as “a Comedy Empire,” is the leading brand in improv-based sketch comedy. Entertainment The company serves as a launching pad for many of the most influential comedians in the world. Alumni include superstars like Chris Farley, Stephen Team Colbert, Bill Murray, John Belushi, Steve Carell, Tina Fey and many others. 11 full-time touring ensembles Once a single stage in Chicago, The Second City now has a corporate Locations communications business, media division, 11 full-time touring ensembles, TV and film operations, as well as training centers and theaters in Chicago, Chicago, Toronto and Toronto and Hollywood. Hollywood Founded The Challenge 1959 With multiple lines of business, The Second City’s network requires significant bandwidth, redundancy and uptime to keep business - and laughs - flowing. Cool Fact The Second City uses their network to process customer transactions, sell Alumni include Tina Fey, tickets online and live-stream shows. John Belushi and Bill Murray On the other side of the stage, directors and students utilize a new online Website system to review footage and scripts. An expansion to the training center even www.secondcity.com includes an on-site area for students to access the online database. For the corporate communications business, The Second City offers downloadable Ecessa Product videos for training sessions. PowerLink® The Second City is also a Google Apps house, fully utilizing the Google Apps suite for business operations. With critical applications like Google Apps living in the Cloud, the ability to stay connected became an even more important function of the business. -

June 17 - 23, 2019 Vol

June 17 - 23, 2019 Vol. 27 No. 24 $2 $1.10 goes to vendor profits J U N E S H I R T S O F T H E M O N T H Calendar GIVEASHIRT.NET 4 Chicago has something for everyone, find out what's happening! SportsWise 6 The world of golf. 7 The Playground Cover Story: Millennium Park 8 Chicago is known for the number of free events it hosts each summer, many of which happen downtown in Millennium Park, where there are so many residents and tourists. As with our Festival Guide, these summer events expose visitors to culture, new points of view and diverse people. Inside StreetWise 15 A Q&A (and some epic photos) with vendor Hozie Williams. Dave Hamilton, Creative Director/Publisher [email protected] Suzanne Hanney, Editor-In-Chief StreetWiseChicago [email protected] Julie Youngquist, Executive Director [email protected] @StreetWise_CHI Amanda Jones, Director of programs [email protected] LEARN MORE AT streetwise.org Ph: 773-334-6600 Office: 4554 N. Broadway, Suite 350, Chicago, IL, 60640 To make a donation to StreetWise, visit our website at www.streetwise.org/donate/ or cut out this form and mail it with your donation to StreetWise, Inc., 4554 N. Broadway, Suite 350, Chicago, IL, 60640. DONATE We appreciate your support! My donation is for the amount of $________________________________Billing Information: Check #_________________Credit Card Type:______________________Name:_________________________________________________________________________________ AVA I L A B L E I N U N I S E X A N D W O M E N ’ S C U T We accept :Visa, Mastercard, Discover or American Express Address:_______________________________________________________________________________ Account#:_____________________________________________________City:___________________________________State:_________________Zip:_______________________ H A N D S C R E E N P R I N T E D T S H I R T S D E S I G N E D B Y L O C A L A R T I S T S I N C H I C A G O , I L . -

Chicago Architecture Center Announces New Neighborhoods and Special 2019 Year of Chicago Theatre Trail for Ninth Open House Chicago, October 19 and 20, 2019

MEDIA CONTACT: Beth Silverman/Lisa Dell The Silverman Group, Inc. 312.932.9950; [email protected] For Immediate Release Chicago Architecture Center announces new neighborhoods and special 2019 Year of Chicago Theatre trail for ninth Open House Chicago, October 19 and 20, 2019 One of the largest architecture festivals in the world, 2019 highlights include: • Designated 2019 Year of Chicago Theatre trail featuring dozens of sites including Broadway In Chicago’s James M. Nederlander Theatre • New neighborhoods include Northwest side expansion with addition of Irving Park, Portage Park, and Jefferson Park • Chicago Architecture Center opens its doors for free admission to signature exhibitions CHICAGO (Sept. 10, 2019) — The Chicago Architecture Center (CAC) today announced the full roster of neighborhoods and sites participating in Open House Chicago 2019—now in its ninth year and one of the largest architecture festivals in the world. This free two-day public event, taking place Saturday and Sunday, October 19 and 20, offers behind-the-scenes access to almost 350 sites in 38 neighborhoods, many rarely open to the public, including repurposed mansions, stunning skyscrapers, opulent theaters, exclusive private clubs, industrial facilities, cutting-edge offices and breathtaking sacred spaces. The new offerings in 2019 include a trail of dozens of theater venues and related sites, literally from A (Adventure Stage Chicago) to Z (Zap Props), celebrating the City’s 2019 Year of Chicago Theatre; an expansion into the Northwest side with the addition of Irving Park, Portage Park, and Jefferson Park joining communities highlighted in previous years of Open House Chicago; and an open invitation to visit the CAC at 111 E.