Finishes Analysis in the Saloon, Fonthill

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Henry Chapman Mercer Fact Sheet

Henry Chapman Mercer Fact Sheet Henry Chapman Mercer (1856-1930) a noted tile-maker, archaeologist, antiquarian, artist and writer, was a leader in the turn-of-the-century Arts and Crafts Movement. ● Henry Chapman Mercer was born in Bucks County, Pennsylvania in 1856 and died at his home, Fonthill, in Doylestown in 1930. ● After graduating from Harvard in 1879, he was one of the founding members of The Bucks County Historical Society in 1880. ● He studied law at The University of Pennsylvania and was admitted to the Philadelphia bar. Mercer never practiced law but turned his interests towards a career in pre-historic archaeology. ● From 1894 to 1897, Mercer was Curator of American and Pre-historic Archaeology at The University of Pennsylvania Museum, Philadelphia. ● As an archaeologist, he conducted site excavations in the Yucatan Peninsula, Mexico, and in the Ohio, Delaware, and Tennessee River valleys. ● In 1897, Mercer became interested in and began collecting "above ground" archaeological evidence of pre-industrial America. ● In searching out old Pennsylvania German pottery for his collection, Mercer developed a keen interest in the craft. By 1899 he was producing architectural tiles that became world famous. ● At fifty-two Mercer began building the first of three concrete structures: Fonthill, 1908-10, his home; the Moravian Pottery and Tile Works, 1910-12, his tile factory; and The Mercer Museum, 1913-16, which housed his collection of early American artifacts. ● Mercer authored Ancient Carpenters Tools and The Bible In Iron. ● Fond of animals and birds, Mercer developed a large arboretum with plants native to Pennsylvania on the grounds of Fonthill. -

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE for More Information, Contact: Gayle Shupack, [email protected]│215.345.0210

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE For more information, contact: Gayle Shupack, [email protected]│215.345.0210. Ext 131 DOYLESTOWN MUSEUMS HOST A DAY OF FREE ADMISSION ON SATURDAY, JULY 16 Doylestown, PA (July 6, 2016) – On Saturday, July 16, four popular attractions in Doylestown- the Mercer Museum, Fonthill Castle, the James A. Michener Art Museum and the Moravian Pottery and Tile Works will offer a day of free admission in celebration of the 100th anniversary of the Mercer Museum. The collaborative Doylestown Museums’ Free Day will take place from 10 a.m. until 5 p.m. Free parking will be available at Fonthill Park and free shuttle service, courtesy of Bucks County Transport will take visitors between Fonthill Park and the Doylestown Cultural District. In the Doylestown Cultural District, visitors can explore the Mercer Museum and James A. Michener Art Museum. The Mercer Museum, a six-story concrete castle opened a century ago by collector and tile-maker, Henry Mercer features his amazing collection of pre-Industrial tools of early America. Visitor can take self-guided tours of the Mercer Museum to see objects like an antique fire engine, horse drawn carriages and more, hanging from different surfaces of the museum, or densely packed in rooms and alcoves. Visitors can also view an eclectic mix of artifacts and memorabilia in the Mercer’s latest exhibition, Long May She Wave: A Graphic History of the American Flag. The exhibit looks at the inventive graphic interpretations of the American Flag as seen in artifacts including Civil War Era flags, Native American moccasins, campaign buttons and children’s toys. -

DECEMBER 1978 $1.00 O

DECEMBER 1978 $1.00 o • e 0~\~ --,..,,./~\~-----~(~ ..~ed ~\~oge~e~ ~____~_. '~o~~-~-~)~'~J~", ~e,.., ~"~ ~.,,,c,.., o~,.~'~ ~,o,. ii!'i~i; !~ NEW, IMPROVED CLAY MIXER ~ii ~ FROM BLUEBIRD MANUFACTURING 1] RUGGED, REDESIGNED FRAME i 2] HEAVY DUTY DRIVE SYSTEM 3] SAFETY SCREEN LOADING PLATFORM 4] THREE POSITION BUCKET--TIPS DOWN TO UNLOAD CLAY 11/2 HP, FAN COOLED MOTOR ON/OFF SAFETY SWITCH WITH PADLOCK EASILY MOVED EASILY CLEANED & MAINTAINED MIXES UP TO 1500 LBSIHR EXCELLENT FOR RECLAIMING SCRAP CLAY LIST PRICES FOS FORT COLLINS FOR SINGLE PHASE 230 VAC (3-Phase 220 VAC Optional) REGULAR STEEL $1325.00 Less Cash Discount STAINLESS STEEL $1795.00 Less Cash Discount SCHOOLS: Contact your dealer or Bluebird for total delivered prices. FOR COMPLETE SPECIFICATIONS & INFORMATION ON OTHER PRODUCTS, WRITE OR CALL: BLUEBIRD MANUFACTURING CO PO BOX 2307 FORT COLLINS, CO 80522 ii 303 484-3243 December 1978 3 4 t /- besides . :5 clay slip glaze? 15 handcrafted pieces of O the fronske handcraft equipt, corp. 525 south mill ave. tempe, az. 85281 (602) 966-3967 Dislribulor Inquiries Welcome 1-1 More inlormalion on the fronske" 'wheel power' mixer I-1 Send me a ironske TM 'whee I power' mixer at $425.00 C.O.D. (we pay the shipping cosls) Name Address City State Zip Make and model of power wheel you own rlducing i'" ~ M 0 N T H L Y eagle Volume 26, Number 10 December 1978 mlcs, nc. 8 Colonial Avenue Letters to the Editor .............................. 7 Wilmington (Elsmere), Suggestions from Our Readers ..................... 9 Delaware 19805 Itinerary ........................................ 11 Where to Show .................................. -

One of Many Rustic East Coast Towns with Which We

A New Yorker’s East Coast Vacation Guide COPYRIGHT © 2019 13 THINGS LTD. All rights reserved. No part of this e-guide may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in articles. For additional information please contact: [email protected]. www.messynessychic.com Copyright © 2019 13 Things Ltd. 1 Long Island The sprawling greenery and rich – as in, Great Gatsby rich – history of Long Island feels worlds apart from the hustle of the city, despite the fact that it’s a stone’s throw from it all. In addition to that old time glamour, Long Island is also home to homey alternatives to the Hamptons. Cozy up to the beachfront B&Bs, mom & pop shops and wineries of the North Shore towns, which know how to put their feet up in truly relaxed summer style… www.messynessychic.com Copyright © 2019 13 Things Ltd. 2 North Fork instead of the Hamptons There’s a reason they call North Fork “the Un-Hamptons.” North Fork compromises a 20 mile stretch of Long Island and is a charming, unpretentious enclave of both beachy and Victorian architecture, great seafood, and delightful mom & pop shops. Where to Stay: Silver Sands Motel: If you’re looking for an American motel just like you saw it in Twin Peaks, take a weekend trip out to Long Island and book yourself a room at the Silver Sands Motel, situated right on the beach at Pipes Cove. These 1960s-era seashore lodgings haven’t changed a lick, and with good reason. -

National Park Service Heister

3,04^ United States Department ofthe Interior NATIONAL PARK SERVICE Northeast Region United States Custom House 200 Chestnut Street Philadelphia, PA 19106 IN REPLY REFER TO: U U L±3 \^ L^=3 u \J L=nir> MAR 1 4 2014 March 13, 2013 INDEPENDENT REGUUTORY REVIEW COMMISSION Environmental Quality Board P.O. Box 8477 Harrisburg, PA 17105-8477 RegComments@pa. gov http://www.ahs.dep.pa.gov/RegComments Subject: 25 PA. Code CH. 78 Proposed Rulemaking: Environmental Protection Performance Standards at Oil and Gas Well Sites Dear Environmental Quality Board members, The National Park Service (NPS) is pleased to provide comment on 25 PA. Code CH. 78 Proposed Rulemaking: Environmental Protection Performance Standards at Oil and Gas Well Sites. The NPS appreciates the proactive steps the Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) is taking in revising these regulations to protect the significant and vital natural resources in the Commonwealth. This effort will result in necessary and important environmental protections for state and federally managed or administered lands, held in trust for the public, and the resources and ecosystem services they provide that are counted upon by present and future generations for essential benefits such as clean water. The NPS offers the following comments which are intended to promote understanding ofthe diverse and nationally significant resources within NPS units and affiliated areas in Pennsylvania, to clarify and strengthen the proposed regulations to aid in a more efficient and effective permitting process, to promote open and early communication between the NPS and PA state regulatory agencies, and to promote the protection of NPS resources. -

Download the PDF Here

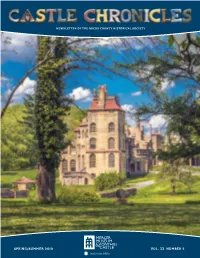

PENNY LOTS SPECIAL FONTHILL ANNIVERSARY EDITION 2012 Newsletter of the Bucks County Historical Society Vol. 26 Number 2 Fonthill Centennial Issue Byers’ Choice Caroler® his issue of Penny Lots house. Informing our research of Henry Mercer commemorates Fonthill’s are the notebooks and meticu- T In celebration of its centen- 100th anniversary. It was May lous records kept by Henry nial Fonthill announces the 1912 when Henry Mercer Mercer. Also included is creation of a Byers’ Choice moved into his castle creation. information on some current Caroler® depicting Henry In this newsletter, we’ll share projects indicating the ongo- Chapman Mercer along with Mercer’s own account of the ing care of the complex prop- his dog, Rollo. Byers’ Choice innovative and experimental erty as the Bucks County Ltd. of Bucks County is well construction of Fonthill, new Historical Society continues known for its Carolers which research on the workers of its stewardship of this are sold around the world. Fonthill, and Mercer’s inspira- National Historic Landmark The figurine will be for tion for components of the for future generations. sale exclusively at Fonthill Castle and Mercer Museum Shop beginning in May. The The Building of “Fonthill” at cost of the Caroler will be $70 Doylestown, Pennsylvania, for Henry Mercer and $20 for In 1908, 1909 and 1910 Rollo; they may be purchased separately. BCHS members Byers’ Choice Caroler® of Copy of a typewritten description found among the receive a 10% discount. For Henry Mercer in tweed pants and papers of Henry Chapman Mercer information contact the Mer- matching vest; he is holding a tile representative of the Moravian everal sketches and mem- cer Museum Shop at muse- Tiles he designed and produced. -

Report Title 14. Jahrhundert 15. Jahrhundert 16. Jahrhundert

Report Title - p. 1 Report Title 14. Jahrhundert 1300-1340 Kunst : Keramik und Porzellan The Fonthill Vase, also called the Gaignières-Fonthill Vase after François Roger de Gaignières and William Beckford's Fonthill Abbey, is a bluish-white Qingbai Chinese porcelain vase. It is the earliest documented Chinese porcelain object to have reached Europe. The vase was made in Jingdezhen, China. 1381 a gift from Ludwig I. von Ungarn to Karl III von Durazzo on his coronation as King of Naples. [Wik,ImpO1:S. 89] 1368-1795 Kunst : Malerei, Kalligraphie, Illustration Die Muslime verwenden in der Kalligraphie eine Kombination von Chinesisch und Arabisch. Künstler verwenden chinesische Zeichen kombiniert mit arabischen Gedichten und Sprichwörtern. [Isr] 15. Jahrhundert 1434 Kunst : Keramik und Porzellan Das älteste chinesische Stück, eine Schale aus chinesischem Seladonporzellan der Ming-Dynastie befindet sich im Hessischen Landesmuseum in Kassel. Auf der spätgotischen vergoldeten Silberfassung ist das Wappen von Graf Philipp von Catzenelnbogen. [Goe1] 1460-1470 Kunst : Keramik und Porzellan Chinese porcelain can be seen depicted in some early Italian paintings. The earliest example found is the bowl in a painting of the Virgin and child by Francesco Benaglio. [ImpO1:S. 90] 16. Jahrhundert 1506-1619 Kunst : Keramik und Porzellan Santos Palace, Lissabon, Portugal. 260 Chinese porcelain dishes and plates. The majority are Ming blue and white wares of the 16th and early 17th centuries to which are added four overglaze enamelled pièces and a few examples of late 17th century ware. Inventarliste des chinesischen Porzellans 1704. [Lion1] 1506-1619 Kunst : Keramik und Porzellan Santa Clara-a-Velha, Kloster in Coimbra, Portugal. -

PENNY LOTS January-June 2012 Newsletter of the Bucks County Historical Society Vol

PENNY LOTS January-June 2012 Newsletter of the Bucks County Historical Society Vol. 26 Number 1 What is the Fonthill’s 100th Anniversary: 1912 – 2012 here does the time go? Why it seems just like Meaning Wyesterday that it was 1912. Surely you of “Penny remember that year? It was the year the Titanic sank, New Mexico and Arizona became states, the Lots”? Girl Scouts of the USA are founded by Juliette In amassing his Gordon Low and Henry Chapman Mercer moved collection Henry Mer- into his new home, Fonthill. cer was known to Yes, it has been nearly 100 years since Henry scour the countryside Mercer wrote, “May 30, 1912 – Took my first meal in search of objects at Fonthill – Frank at lunch – Band playing in made obsolete by the cemetery – Decoration Day.” With Henry’s note in industrial era. In addi- tion to searching mind we will celebrate this anniversary throughout through barns and 2012. To celebrate the achievement, inspiration and garrets, he acquired imagination of Fonthill we will be holding special many artifacts sold programs and activities throughout the year. A as “penny lots” at special issue of Penny Lots will be devoted to local auctions. Our Fonthill’s 100th Anniversary. In addition keep newsletter’s name checking in with the BCHS website and Henry honors that tradition. Early view of Fonthill; note original spring house in Chapman Mercer Facebook page for updated foreground before Mercer transformed it. information and dates! The Aprons Are Coming – and Other Exhibits very full and diverse slate tecting treasure and the mod- coming! The exhibition, Aof exhibits is scheduled for ern treasure hunt. -

From Philadelphia Country House to City Recreation Center

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Theses (Historic Preservation) Graduate Program in Historic Preservation 2016 From Philadelphia Country House to City Recreation Center: Uncovering the Architectural History of the Building Known Successively as Blockley Retreat, Kirkbride Mansion, and Lee Cultural Center Through Building Archaeology Joseph C. Mester University of Pennsylvania Follow this and additional works at: http://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses Part of the Architectural History and Criticism Commons, and the Historic Preservation and Conservation Commons Mester, Joseph C., "From Philadelphia Country House to City Recreation Center: Uncovering the Architectural History of the Building Known Successively as Blockley Retreat, Kirkbride Mansion, and Lee Cultural Center Through Building Archaeology" (2016). Theses (Historic Preservation). Paper 598. http://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses/598 Suggested Citation: Mester, Joseph C. (2016). From Philadelphia Country House to City Recreation Center: Uncovering the Architectural History of the Building Known Successively as Blockley Retreat, Kirkbride Mansion, and Lee Cultural Center Through Building Archaeology. (Masters Thesis). University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA. This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. http://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses/598 For more information, please contact [email protected]. From Philadelphia Country House to City Recreation Center: Uncovering the Architectural History of the Building Known Successively as Blockley Retreat, Kirkbride Mansion, and Lee Cultural Center Through Building Archaeology Abstract In this thesis, I analyze the Federal style country house, initiated in 1794, that stands today near the corner of 44th Street and Haverford Avenue in West Philadelphia. As it aged, the owners and occupants slowly transformed the country house from a private “country seat” to a public recreation center in the midst of a dense urban neighborhood. -

Summer-Fall 2015 Newsletter of the Bucks County Historical Society Vol

Summer-Fall 2015 Newsletter of the Bucks County Historical Society Vol. 29 Number 2 IN THIS ISSUE: • EXHIBITS AT THE MERCER • RECENT ACQUISITIONS • FONTHILL TILE STUDY • FONTHILL’S NORTH STREET GATE • MERCER’S FAMILY PETS • SAVE THE DATE: COCKTAILS AT THE CASTLE • AND MORE! “Volunteer Firefighting” Members Preview Event on April 23. (L-R): Philadelphia Fire Commissioner, Derrick Sawyer with BCHS Board Chair, Bill Maeglin. The Tilley Family L to R: Elizabeth, Doug, Sam, Nancy, Jack, Michael and Barbara. (L-R): Trustee Gus Perea, Pete Van Dine and Linda Goodwin representing exhibit sponsor, Bucks County Foundation with BCHS donors Tina and Jim Greenwood BCHS Executive Director, Doug Dolan 2 Donor and Volunteer Recognition Celebration on May 12 Volunteers receive awards from left: Trustee Brian McLeod with Volunteer Coordinator, Frances Boffa; Trustees, Maureen B. Carlton and Michael Raphael; Jesse Crooks and Tim German. (L-R): Doris Carr and Amy Parenti. (L-R): Joan and Frank Whalon with Darlene and Dan Dean. Charles Yeske, Manager Moravian Pottery & Tile Works pours drinks for guests. SEE THE ARTICLE ABOUT THE Delware Valley Saxaphone Quartet L to R: Mike Seifried, Don Kline, William R. Schutt and Brian Freer. RECOGNITION EVENT ON PAGE 15 . 3 Firefighting Exhibit Opens THE NEW ORLEANS EXCURSIONISTS OF THE VOLUNTEER FIREMEN’S ASSOCIATION OF PHILADELPHIA. Rile and Company, Philadelphia, 1888. This photo shows VFA members in front of the Union League just before their departure for New Orleans. Gift of the Volunteer Firemen’s Association of Philadelphia, 1919. n April 25, the Mercer Museum Mississippi Engine Company No. 2, was volunteer era. -

Spring-Summer 2019 Newsletter

Newsletter of the Bucks County Historical Society SprinG/Summer 2019 Vol. 33 Number 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Message from the Executive Director ............................3 A New Catering Partner for the Castles ..........................4 Board of Trustees Recent Grants Benefit Projects across the Mercer Mile ...........4 OFFICERS Welcome Our New Staff ......................................... Chair Heather A. Cevasco 5 Vice-Chair Maureen B. Carlton Vice-Chair Linda B. Hodgdon Plus Ultra Society Spotlight. Treasurer Thomas Hebel 5 Secretary William R. Schutt Past Chair John R. Augenblick Summer 2019 Exhibit Preview: From Here to There ...............6 TRUSTEES Tobi Bruhn Richard D. Paynton, Jr. Summer 2019 Exhibit Preview: Kelly Cwiklinski Michelle A. Pedersen Making Astronauts: Bucks County to the Moon ................... Susan E. Fisher Gustavo I. Perea 7 David L. Franke Michael B. Raphael Elizabeth H. Gemmill Jack Schmidt Making Astronauts: Bucks County to the Moon – Christine Harrison Susan J. Smith Verna Hutchinson Tom Thomas Artifact Spotlight ................................................8 Michael S. Keim Rochelle Thompson William D. Maeglin Anthony S. Volpe Community Partner: Johnsville Centrifuge Brian R. McLeod Steven T. Wray and Science Museum ............................................9 President & Executive Director Kyle McKoy “Witnessing History” – Jury Chairs Added to Museum Collection .....................10 GENERAL INFORMATION MERCER MUSEUM & MUSEUM SHOP Preserving Bucks County History – 84 South Pine Street, Doylestown, PA 18901 One Deed Book at a Time .....................................11 215-345-0210 Hours: Monday – Saturday, 10:00 a.m. – 5:00 p.m. Collections Connection .......................................12 Sunday, noon – 5:00 p.m. Research Library Hours: The A. Oscar Martin Bridge Architectural Plans ...............13 Tuesday – Thursday, 1:00 p.m. – 5:00 p.m. Friday & Saturday, 10:00 a.m. -

Fred Moten Black-Studies Provocateur

PlantPlant ProspectingProspecting inin ChinaChina •• Prodigies,Prodigies, ThenThen andand NowNow JANUARY-FEBRUARY 2018 • $4.95 Fred Moten Black-studies provocateur Reprinted from Harvard Magazine. For more information, contact Harvard Magazine, Inc. at 617-495-5746 Seeking great leaders. The Harvard Advanced Leadership Initiative off ers a calendar year of rigorous education and refl ection for highly accomplished leaders in business, government, law, medicine, and other sectors who are transitioning from their primary careers to their next years of service. Led by award-winning faculty members from across Harvard, the program aims to deploy a new leadership force tackling the world’s most challenging social and environmental problems. be inspired at +1-617-496-5479 Reprinted from Harvard Magazine. For more information, contact Harvard Magazine, Inc. at 617-495-5746 2017.11.17_ALI_Ivy_Ad_v1.indd180108_ALI.indd 1 1 11/17/1711/17/17 11:16 1:10 PMAM JANUARY-FEBRUARY 2018, VOLUME 120, NUMBER 3 FEATURES 32 Botanizing in the “Mother of Gardens” | by Jonathan Shaw Seeking seeds and specimens in Sichuan 40 Vita: Henry Chapman Mercer | by Nancy Freudenthal Brief life of an innovative ceramicist: 1856-1930 42 The Low End Theory | by Jesse McCarthy p. 32 Fred Moten’s edgy approach to black studies 46 Prodigies’ Progress | by Ann Hulbert Parents and superkids, yesterday and today JOHN HARVARD’S JOURNAL 14 The Kennedy School redux debuts, financial surpluses— and warning signs, enthusiastic archivist, a taxing time for endowments, the Medical School agenda, dean of freshmen to depart, Samuel Huntington as prophet, social-club penalties imposed, a Maharishi moment, a Harvardian teaches hip-hop in Hangzhou, the University marshal moves on, honoring authors and artists, an unexpectedly dreary football campaign, and a speedy swimmer p.