LING3412 Final Paper Edited for Neulingwp V3

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

England Singles TOP 100 2019 / 25 22.06.2019

22.06.2019 England Singles TOP 100 2019 / 25 Pos Vorwochen Woc BP Titel und Interpret 2019 / 25 - 1 11151 5 I Don't Care . Ed Sheeran & Justin Bieber 222121 2 Old Town Road . Lil Nas X 333241 7 Someone You Loved . Lewis Capaldi 44471 2 Vossi Bop . Stormzy 555112 Bad Guy . Billie Eilish 67764 Hold Me While You Wait . Lewis Capaldi 78896 SOS . Avicii feat. Aloe Blacc 8 --- --- 1N8 No Guidance . Chris Brown feat. Drake 99939 Cross Me . Ed Sheeran feat. Chance The Rapper & PnB Rock 10 11 11 1110 All Day And Night . Jax Jones & Martin Solveig pres. Europa . 11 10 10 69 If I Can't Have You . Shawn Mendes 12 --- 14 309 Grace . Lewis Capaldi 13 15 --- 213 Shine Girl . MoStack feat. Stormzy 14 13 --- 213 Never Really Over . Katy Perry 15 24 39 315 Wish You Well . Sigala & Becky Hill 16 17 13 73 Me! . Taylor Swift feat. Brendon Urie Of Panic! At The Disco 17 6 6 132 Piece Of Your Heart . Meduza feat. Goodboys 18 --- --- 1N18 Mad Love . Mabel 19 --- --- 1N19 Stinking Rich . MoStack feat. Dave & J Hus 20 --- --- 1N20 Heaven . Avicii . 21 22 18 318 The London . Young Thug feat. J. Cole & Travi$ Scott 22 --- --- 1N22 Shockwave . Liam Gallagher 23 30 31 323 One Touch . Jesse Glynne & Jax Jones 24 27 23 618 Guten Tag . Hardy Caprio & DigDa T 25 14 --- 214 What Do You Mean . Skepta feat. J Hus 26 43 48 1526 Ladbroke Grove . AJ Tracey 27 34 29 327 Easier . 5 Seconds Of Summer 28 18 47 518 Greaze Mode . -

Risktaking Behavior in Juvenile Myoclonic Epilepsy

FULL-LENGTH ORIGINAL RESEARCH Risk-taking behavior in juvenile myoclonic epilepsy *†Britta Wandschneider, *†Maria Centeno, *†‡Christian Vollmar, *†Jason Stretton, §Jonathan O’Muircheartaigh, *†Pamela J. Thompson, ¶Veena Kumari, *†Mark Symms, §Gareth J. Barker, *†John S. Duncan, #Mark P. Richardson, and *†Matthias J. Koepp Epilepsia, 0(0):1–8, 2013 doi: 10.1111/epi.12413 SUMMARY Objective: Patients with juvenile myoclonic epilepsy (JME) often present with risk-tak- ing behavior, suggestive of frontal lobe dysfunction. Recent studies confirm functional and microstructural changes within the frontal lobes in JME. This study aimed at char- acterizing decision-making behavior in JME and its neuronal correlates using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI). Methods: We investigated impulsivity in 21 JME patients and 11 controls using the Iowa Gambling Task (IGT), which measures decision making under ambiguity. Perfor- mance on the IGT was correlated with activation patterns during an fMRI working memory task. Results: Both patients and controls learned throughout the task. Post hoc analysis revealed a greater proportion of patients with seizures than seizure-free patients hav- ing difficulties in advantageous decision making, but no difference in performance between seizure-free patients and controls. Functional imaging of working memory networks showed that overall poor IGT performance was associated with an increased Dr. Wandschneider is activation in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) in JME patients. Impaired registrar in neurology learning during the task and ongoing seizures were associated with bilateral medial and is pursuing a PhD prefrontal cortex (PFC) and presupplementary motor area, right superior frontal at the UCL Institute of gyrus, and left DLPFC activation. Neurology. -

Ebook Download This Is Grime Ebook, Epub

THIS IS GRIME PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Hattie Collins | 320 pages | 04 Apr 2017 | HODDER & STOUGHTON | 9781473639270 | English | London, United Kingdom This Is Grime PDF Book The grime scene has been rapidly expanding over the last couple of years having emerged in the early s in London, with current grime artists racking up millions of views for their quick-witted and contentious tracks online and filling out shows across the country. Sign up to our weekly e- newsletter Email address Sign up. The "Daily" is a reference to the fact that the outlet originally intended to release grime related content every single day. Norway adjusts Covid vaccine advice for doctors after admitting they 'cannot rule out' side effects from the Most Popular. The awkward case of 'his or her'. Definition of grime. This site uses cookies. It's all fun and games until someone beats your h Views Read Edit View history. During the hearing, David Purnell, defending, described Mondo as a talented musician and sportsman who had been capped 10 times representing his country in six-a-side football. Fernie, aka Golden Mirror Fortunes, is a gay Latinx Catholic brujx witch — a combo that is sure to resonate…. Scalise calls for House to hail Capitol Police officers. Drill music, with its slower trap beats, is having a moment. Accessed 16 Jan. This Is Grime. From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. More On: penn station. Police are scrambling to recover , pieces of information which were WIPED from records in blunder An unwillingness to be chained to mass-produced labels and an unwavering honesty mean that grime is starting a new movement of backlash to the oppressive systems of contemporary society through home-made beats and backing tracks and enraged lyrics. -

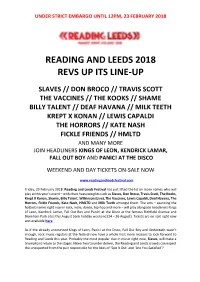

Reading and Leeds 2018 Revs up Its Line-Up

UNDER STRICT EMBARGO UNTIL 12PM, 23 FEBRUARY 2018 READING AND LEEDS 2018 REVS UP ITS LINE-UP SLAVES // DON BROCO // TRAVIS SCOTT THE VACCINES // THE KOOKS // SHAME BILLY TALENT // DEAF HAVANA // MILK TEETH KREPT X KONAN // LEWIS CAPALDI THE HORRORS // KATE NASH FICKLE FRIENDS // HMLTD AND MANY MORE JOIN HEADLINERS KINGS OF LEON, KENDRICK LAMAR, FALL OUT BOY AND PANIC! AT THE DISCO WEEKEND AND DAY TICKETS ON-SALE NOW www.readingandleedsfestival.com Friday, 23 February 2018: Reading and Leeds Festival has just lifted the lid on more names who will play at this year’s event – with chart heavyweights such as Slaves, Don Broco, Travis Scott, The Kooks, Krept X Konan, Shame, Billy Talent, Wilkinson (Live), The Vaccines, Lewis Capaldi, Deaf Havana, The Horrors, Fickle Friends, Kate Nash, HMLTD and Milk Teeth amongst them. The acts – spanning the hottest names right now in rock, indie, dance, hip-hop and more – will play alongside headliners Kings of Leon, Kendrick Lamar, Fall Out Boy and Panic! at the Disco at the famous Richfield Avenue and Bramham Park sites this August bank holiday weekend (24 – 26 August). Tickets are on-sale right now and available here. As if the already announced Kings of Leon, Panic! at the Disco, Fall Out Boy and Underøath wasn’t enough, rock music regulars at the festival now have a whole host more reasons to look forward to Reading and Leeds this year. Probably the most popular duo in music right now, Slaves, will make a triumphant return to the stages. Never two to under deliver, the Reading and Leeds crowds can expect the unexpected from the pair responsible for the likes of ‘Spit It Out’ and ‘Are You Satisfied’? UNDER STRICT EMBARGO UNTIL 12PM, 23 FEBRUARY 2018 With another top 10 album, ‘Technology’, under their belt, Don Broco will be joining the fray this year. -

Grime + Gentrification

GRIME + GENTRIFICATION In London the streets have a voice, multiple actually, afro beats, drill, Lily Allen, the sounds of the city are just as diverse but unapologetically London as the people who live here, but my sound runs at 140 bpm. When I close my eyes and imagine London I see tower blocks, the concrete isn’t harsh, it’s warm from the sun bouncing off it, almost comforting, council estates are a community, I hear grime, it’s not the prettiest of sounds but when you’ve been raised on it, it’s home. “Grime is not garage Grime is not jungle Grime is not hip-hop and Grime is not ragga. Grime is a mix between all of these with strong, hard hitting lyrics. It's the inner city music scene of London. And is also a lot to do with representing the place you live or have grown up in.” - Olly Thakes, Urban Dictionary Or at least that’s what Urban Dictionary user Olly Thake had to say on the matter back in 2006, and honestly, I couldn’t have put it better myself. Although I personally trust a geezer off of Urban Dictionary more than an out of touch journalist or Good Morning Britain to define what grime is, I understand that Urban Dictionary may not be the most reliable source due to its liberal attitude to users uploading their own definitions with very little screening and that Mr Thake’s definition may also leave you with more questions than answers about what grime actually is and how it came to be. -

The Futurism of Hip Hop: Space, Electro and Science Fiction in Rap

Open Cultural Studies 2018; 2: 122–135 Research Article Adam de Paor-Evans* The Futurism of Hip Hop: Space, Electro and Science Fiction in Rap https://doi.org/10.1515/culture-2018-0012 Received January 27, 2018; accepted June 2, 2018 Abstract: In the early 1980s, an important facet of hip hop culture developed a style of music known as electro-rap, much of which carries narratives linked to science fiction, fantasy and references to arcade games and comic books. The aim of this article is to build a critical inquiry into the cultural and socio- political presence of these ideas as drivers for the productions of electro-rap, and subsequently through artists from Newcleus to Strange U seeks to interrogate the value of science fiction from the 1980s to the 2000s, evaluating the validity of science fiction’s place in the future of hip hop. Theoretically underpinned by the emerging theories associated with Afrofuturism and Paul Virilio’s dromosphere and picnolepsy concepts, the article reconsiders time and spatial context as a palimpsest whereby the saturation of digitalisation becomes both accelerator and obstacle and proposes a thirdspace-dromology. In conclusion, the article repositions contemporary hip hop and unearths the realities of science fiction and closes by offering specific directions for both the future within and the future of hip hop culture and its potential impact on future society. Keywords: dromosphere, dromology, Afrofuturism, electro-rap, thirdspace, fantasy, Newcleus, Strange U Introduction During the mid-1970s, the language of New York City’s pioneering hip hop practitioners brought them fame amongst their peers, yet the methods of its musical production brought heavy criticism from established musicians. -

England Singles TOP 100 2019 / 52 28.12.2019

28.12.2019 England Singles TOP 100 2019 / 52 Pos Vorwochen Woc BP Titel und Interpret 2019 / 52 - 1 1 --- --- 1N1 1 I Love Sausage Rolls . LadBaby 22342 Own It . Stormzy feat. Ed Sheeran & Burna Boy 34252 Before You Go . Lewis Capaldi 43472 Don't Start Now . Dua Lipa 5713922 Last Christmas . Wham! 6 --- --- 1N6 Audacity . Stormzy feat. Headie One 75575 Roxanne . Arizona Zervas 8681052 All I Want For Christmas Is You . Mariah Carey 9 --- --- 1N9 Lessons . Stormzy 10 1 1 201 11 Dance Monkey . Tones And I . 11 8 14 48 River . Ellie Goulding 12 11 --- 211 Adore You . Harry Styles 13 9 6 53 Everything I Wanted . Billie Eilish 14 14 22 1082 Fairytale Of New York . The Pogues & Kirsty McColl 15 12 11 296 Bruises . Lewis Capaldi 16 16 26 751 2 Merry Christmas Everyone . Shakin' Stevens 17 15 23 781 5 Do They Know It's Christmas ? . Band Aid 18 47 55 518 Watermelon Sugar . Harry Styles 19 24 39 3910 Step Into Christmas . Elton John 20 17 12 312 Blinding Lights . The Weeknd . 21 19 18 1314 Hot Girl Bummer . Blackbear 22 21 15 93 Lose You To Love Me . Selena Gomez 23 23 20 1020 Pump It Up . Endor 24 25 32 347 It's Beginning To Look A Lot Like Christmas . Michael Bublé 25 29 43 283 One More Sleep . Leona Lewis 26 35 40 426 Falling . Trevor Daniel 27 51 --- 3210 Lucid Dreams . Juice WRLD 28 31 33 2813 Santa Tell Me . Ariana Grande 29 34 44 804 I Wish It Could Be Christmas Everyday . -

{Download PDF} Cultural Traditions in the United Kingdom

CULTURAL TRADITIONS IN THE UNITED KINGDOM PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Lynn Peppas | 32 pages | 24 Jul 2014 | Crabtree Publishing Co,Canada | 9780778703136 | English | New York, Canada Cultural Traditions in the United Kingdom PDF Book Retrieved 11 July It was designed by Sir Giles Gilbert Scott in and was launched by the post office as the K2 two years after. Under the Labour governments of the s and s most secondary modern and grammar schools were combined to become comprehensive schools. Due to the rise in the ownership of mobile phones among the population, the usage of the red telephone box has greatly declined over the past years. In , scouting in the UK experienced its biggest growth since , taking total membership to almost , We in Hollywood owe much to him. Pantomime often referred to as "panto" is a British musical comedy stage production, designed for family entertainment. From being a salad stop to housing a library of books, ingenious ways are sprouting up to save this icon from total extinction. The Tate galleries house the national collections of British and international modern art; they also host the famously controversial Turner Prize. Jenkins, Richard, ed. Non-European immigration in Britain has not moved toward a pattern of sharply-defined urban ethnic ghettoes. Media Radio Television Cinema. It is a small part of the tartan and is worn around the waist. Help Learn to edit Community portal Recent changes Upload file. At modern times the British music is one of the most developed and most influential in the world. Wolverhampton: Borderline Publications. Initially idealistic and patriotic in tone, as the war progressed the tone of the movement became increasingly sombre and pacifistic. -

Brittiska Rapparen Giggs Till Stockholm!

GIGGS TILL SVERIGE! 2018-02-20 19:00 CET BRITTISKA RAPPAREN GIGGS TILL STOCKHOLM! ”Linguo”, ”Peligro”, ”Talkin The Hardest” och “Lock Doh” är bara några av Giggs monster till låtar. Han är en av Englands hetaste rappare just nu och har onekligen varit det sedan debutalbumet ”Walk in da Park” från 2008. Aktuell med senaste släppet ”Wamp 2 Dem” kommer Giggs nu äntligen till Sverige! 17 april på Debaser Strand i Stockholm! Biljetter släpps fredag 23 februari kl. 10.00 via LiveNation.se! Med sitt karaktäristiska flow, unika röst, kreativa texter och underfundiga punchlines är Giggs rapparen fansen vill lyssna på och artister vill jobba med. 2 Chainz, Popcaan och Young Thug gästade på hans senaste mixtape ”Wamp 2 Dem” – som landade på andraplatsen på UK Album Chart när det släpptes, trots att det inte var ett traditionellt studioalbum. Giggs har utsetts till ”Best Artist” på Rated Awards och nominerats till ”Best Album” och ”Best Hiphop Act” på MOBO Awards samt nominerats till ”Best International Act: Europe” på senaste BET Awards i USA. Det råder ingen tvekan om att Giggs är en av de största i gemet just nu. Vår och gig med Giggs - kan det bli bättre? Ses på Debaser Strand 17 april! Datum 17/4 - Debaser Strand, Stockholm Biljetter Biljetter släpps fredag 23 februari kl. 10.00 via LiveNation.se Pressbiljetter & fotopass Ansökan om köp av pressbiljett skickas till [email protected]. Det är viktigt att du skickar en förfrågan per artist/evenemang och att du i ämnesraden anger vilken artist/evenemang det gäller. Fotopass-ansökan görs via photorequest.livenation.se (notera att godkänt fotopass inte gäller som biljett). -

Most Requested Songs of 2019

Top 200 Most Requested Songs Based on millions of requests made through the DJ Intelligence music request system at weddings & parties in 2019 RANK ARTIST SONG 1 Whitney Houston I Wanna Dance With Somebody (Who Loves Me) 2 Mark Ronson Feat. Bruno Mars Uptown Funk 3 Journey Don't Stop Believin' 4 Cupid Cupid Shuffle 5 Neil Diamond Sweet Caroline (Good Times Never Seemed So Good) 6 Walk The Moon Shut Up And Dance 7 Justin Timberlake Can't Stop The Feeling! 8 Earth, Wind & Fire September 9 Usher Feat. Ludacris & Lil' Jon Yeah 10 V.I.C. Wobble 11 DJ Casper Cha Cha Slide 12 Outkast Hey Ya! 13 Black Eyed Peas I Gotta Feeling 14 Bon Jovi Livin' On A Prayer 15 ABBA Dancing Queen 16 Bruno Mars 24k Magic 17 Garth Brooks Friends In Low Places 18 Spice Girls Wannabe 19 AC/DC You Shook Me All Night Long 20 Kenny Loggins Footloose 21 Backstreet Boys Everybody (Backstreet's Back) 22 Isley Brothers Shout 23 B-52's Love Shack 24 Van Morrison Brown Eyed Girl 25 Bruno Mars Marry You 26 Miley Cyrus Party In The U.S.A. 27 Taylor Swift Shake It Off 28 Luis Fonsi & Daddy Yankee Feat. Justin Bieber Despacito 29 Montell Jordan This Is How We Do It 30 Beatles Twist And Shout 31 Ed Sheeran Thinking Out Loud 32 Sir Mix-A-Lot Baby Got Back 33 Maroon 5 Sugar 34 Ed Sheeran Perfect 35 Def Leppard Pour Some Sugar On Me 36 Killers Mr. Brightside 37 Pharrell Williams Happy 38 Toto Africa 39 Chris Stapleton Tennessee Whiskey 40 Flo Rida Feat. -

Hannah Edwards Costume Designer

Lux Artists Ltd. 12 Stephen Mews London W1T 1AH +44 (0)20 7637 9064 www.luxartists.net HANNAH EDWARDS COSTUME DESIGNER FILM/TELEVISION DIRECTOR PRODUCER LE MONDE OU RIEN Romain Gavras Iconoclast Cast: Vincent Cassel, Isabelle Adjani CATCH ME DADDY Daniel Wolfe Emu Films Cast: Sameena Jabeen Ahmed, Connor McCarron, Gary Lewis Film 4 Official Selection, Cannes Film Festival (2014) Official Selection, London Film Festival (2014) DIRECTORS/COMMERCIALS FLEUR FORTUNÉ Nike NINIAN DOFF Temptations ARNI THOR JONSSON Gumtree DANIEL WOLFE Honda, Chivas Regal, Tesco, Guiness, Cobra Beer, Tourism Ireland, Vodafone, Thalys, Mars, Kopparberg Cider, San Miguel, Three Mobile, Hennessy ROMAIN GAVRAS Louis Vuitton, Bacardi, Samsung Winner, Best Styling, Silver British Arrow Awards, 2014, Blue Lagoon, Blu NICK GORDON Chambord, GreenFlag, Boots, Stella Artois, Axe CANADA Tomorrowland, SFR, Cravendale GUSTAV JOHANSSON Samsung SAAM FARAHMAND Guinness, Nokia ERIC LYNN HSBC, John Lewis Christmas, Lactose Free Milk DAWN SHADFORTH Right Move, Matalan KIM GEHRIG Sport England, Netflix, Vodafone, Cadburys, Ikea, Clearasil, Channel 5, Honda, John Lewis, Sport England BOB HARLOW Nokia CHRISTIAN LARSON Nexxus STIAN SMESTAD Tesco AB/CD/CD Samsung BEN CONRAD Castro Oil DIRECTORS/MUSIC VIDEOS DAWN SHADFORTH Metronomy “Old Skool” DANIEL WOLFE Plan B “Writing’s on the Wall”, “Love Goes Down”, “The Recluse”, “Prayin”, “She Said”, “Stay Too Long” Winner, Best Styling, MVA 2010, The Joy Formidable “The Greatest Light”, Chase and Status “Blind Faith” Winner, Best Styling, MVA 2011, James Morrison “Get To You”, The Energies “Born Again Runner”, Take that “Up All Night”, Duffy “Warwick Avenue”, Hadouken “Declaration of War”, Roisin Murphy “Let Me Know” ROMAIN GAVRAS Jay Z feat. -

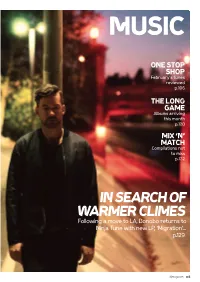

IN SEARCH of WARMER CLIMES Following a Move to LA, Bonobo Returns to Ninja Tune with New LP, ‘Migration’

MUSIC ONE STOP SHOP February’s tunes reviewed p.106 THE LONG GAME Albums arriving this month p.128 MIX ‘N’ MATCH Compilations not to miss p.132 IN SEARCH OF WARMER CLIMES Following a move to LA, Bonobo returns to Ninja Tune with new LP, ‘Migration’... p.129 djmag.com 105 HOUSE BEN ARNOLD QUICKIES Roberto Clementi Avesys EP [email protected] Pets Recordings 8.0 Sheer class from Roberto Clementi on Pets. The title track is brooding and brilliant, thick with drama, while 'Landing A Man'’s relentless thump betrays a soft and gentle side. Lovely. Jagwar Ma Give Me A Reason (Michael Mayer Does The Amoeba Remix) Marathon MONEY 8.0 SHOT! Showing that he remains the master (and managing Baba Stiltz to do so in under seven minutes too), Michael Mayer Is Everything smashes this remix of baggy dance-pop dudes Studio Barnhus Jagwar Ma out of the park. 9.5 The unnecessarily young Baba Satori Stiltz (he's 22) is producing Imani's Dress intricate, brilliantly odd house Crosstown Rebels music that bearded weirdos 8.0 twice his age would give their all chopped hardcore loops, and a brilliance from Tact Recordings Crosstown is throwing weight behind the rather mid-life crises for. Think the bouncing bassline. Sublime work. comes courtesy of roadman (the unique sound of Satori this year — there's an album dizzying brilliance of Robag small 'r' is intentional), aka coming — but ignore the understatedly epic Ewan Whrume for a reference point, Dorsia Richard Fletcher. He's also Tact's Pearson mixes of 'Imani's Dress' at your peril.