The Nursery Brotherhood in the First House of Zeta Psi

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Phi Beta Delta and Rituals' Rewards

International Research and Review, Journal of Phi Beta Delta Honor Society Volume 9, Number 1, Fall 2019 for International Scholars Editor's Note: The following article is reprinted (with updated format and editing) from the archives of the Phi Beta Delta International Review, Volume VII, Spring 1998, pp. 75-86. The International Review is the predecessor of the current publication. It is re-printed here to provide international educators with an historical view of scholarship on honor societies. Phi Beta Delta and Rituals’ Rewards Guillermo De Los Reyes University of Houston Paul Rich Policy Studies Organization The growth of Phi Beta Delta cannot be attributed to any one cause. World interest in globalization and in cultural and education exchanges, along with the happy coincidence of a number of enthusiastic leaders, is certainly part of the explanation. However, it was the decision that it should be a Greek honorary society with the accompanying rituals of the Greek tradition which was a fateful for its success.1 Injunctions to chapters to have a meaningful induction ceremony take on more weight when Phi Beta Delta is put into historic perspective as an organization with ritual - not an enormous amount, but then, like garlic, a little goes a long way. Although Greek academic societies are not nearly as concerned with ritual as are other ritualistic organizations such as, the Freemans, the Shriners, or the DeMolay, their success owes something to the medals, mottos and shields. What would Phi Beta Kappa be without its key? Organizations with ritual often fare better than those without. It is an unpleasant corollary, but makes the point, to recall that the segregationist White Citizens’ Councils members with their business suits never achieved the success of the Ku Klux Klan with its hoods and flowing robes. -

FRMT 2002 Fall

Acacia Alpha Epsilon Pi Alpha Gamma Rho Alpha Kappa Lambda Alpha Sigma Phi Alpha Tau Omega Chi Phi Delta Chi Delta Tau Delta Delta Upsilon FarmHouse Kappa Alpha Order Kappa Delta Rho Phi Kappa Psi Phi Kappa Tau Phi Kappa Theta Pi Kappa Phi Pi Lambda Phi Psi Upsilon Theta Xi Zeta Beta Tau Zeta Psi Acacia Alpha Epsilon Pi Alpha Gamma Rho Alpha Kappa Lambda Alpha Sigma Phi Alpha Tau Omega Chi Phi Delta Chi Delta Tau Delta Delta Upsilon FarmHouse Kappa Alpha Order Kappa Delta Rho Phi Kappa Psi Phi Kappa Tau Phi KappaFRMT Theta Pi Kappa Phi Pi Lambda News Phi Psi Upsilon Theta Xi Zeta Beta Tau Zeta Psi The FRMT Risk Management Newsletter, prepared by HRH/Kirklin & Co., LLC. Volume 13 Spring 2004 Staying Cool under the Gun: Understanding the Do’s and Don’ts of Crisis Management by Dave Westol - Executive Director Punctuate the rumors and determine what Theta Chi Fraternity actually occurred. This will take time. Take Assume that members will keep the the time to get things right. situation to themselves. Remind everyone The call always seems to come at 2:35 a.m. that now is the time for members to support The voice is anxious, the tone ranging from Hold a meeting of members and new each other, and that means not discussing serious to frightened. Facts are in short members. Unorthodox circumstances call for the situation with those persons outside of supply, but rumor, innuendo and “I heard...” unorthodox responses. Better to meet at 2:30 the chapter. statements are plentiful. -

Liquor? I 'Ardly Know 'Er! Part I: Wine 1

Hour 1: Liquor? I 'ardly know 'er! Part I: Wine 1. This type of wine, made from the petals of its source plant and sugar, shares its name with a 1957 Ray Bradbury novel. Dandelion wine 2. In James Joyce’s Ulysses, with what type of wine does Bloom accompany his gorgonzola cheese sandwich? Burgundy 3. What are the five Premiers Grands Crus Bordeaux? Lafite-Rothschild, Mouton-Rothschild, Latour, Haut-Brion and Margaux 4. Which one was not originally Premier Grand Cru? Mouton-Rothschild 5. The movie Bottleshock tells the story of Californian wines first beating French wines in a blind- tasting. In what year did it occur? 1976 6. What wine is Paul Giamatti’s character saving for a special occasion in Sideways? 61 Cheval Blanc 7. What type of wine did Hannibal Lector pair with a census taker once? Chianti 8. Where would you find the sea referred to as “wine-dark”? Homer 9. According to legend, what dish was created following Henry IV's coining of the phrase "a chicken in every pot!" coq au vin 10. What dish did Julia Child prepare on the premiere of "The French Chef"? boeuf bourgoignon 11. What is the name of the wine that Falstaff drinks? Sack For the following dishes, say whether it should be prepared with white or red wine. 12. steak red 13. chicken white 14. fish white 15. lobster white 16. spaghetti carbonara white 17. bread with goat cheese red Part II: Beer 18. What brewery sent a truckload of “Winner Beer” to the White House the day that Prohibition was repealed? Yuengling 19. -

Greek Houses

2 Greek houses Σ Δ Σ Σ Ζ ΚΑ Υ Α 33rd Street Θ Τ ΛΧΑ Δ ΝΜ ΤΕΦ ΑΦ Ξ Α Fresh Τ Grocer Radian Hill ΚΑΘ ΖΨ Walnut Street Walnut Street 34th Street ΣΦΕ Du Bois GSE Street 37th 39th Street Annenberg Van Pelt Α Rotunda ΠΚΦ ∆ Movie Huntsman Π Hillel ΑΧΡ theater Rodin ΔΦ SP2 Woodland Walk Locust Walk ΑΤΩ ΣΧ Locust Walk ΔΨ ΦΓΔ 3609-11 36th Street Fisher Class of 1920 Commons ΚΣ Φ Fine 38th Street 40th Street Δ Harnwell Steinberg- Arts McNeil Θ Deitrich ΨΥ College Hall Cohen Harrison ΖΒΤ Houston Irvine Van Pelt Σ Α Β Wistar Williams Α Χ Θ Allegro 41st Street 41st Spruce Street Ε Ω Π Spruce Street Δ Φ The Quad Δ Κ Stouffer ΔΚΕ Δ Ψ Σ Χ ΠΠ Κ Ω Κ Λ HUP N ΑΦ Vet school Pine Street Chapter Letters Address Page Chapter Letters Address Page Chapter Letters Address Page Alpha Chi Omega* ΑΧΩ 3906 Spruce St. 9 Kappa Alpha Society ΚΑ 124 S. 39th St. 15 Sigma Alpha Mu ΣΑΜ 3817 Walnut St. 17 Alpha Chi Rho ΑΧΡ 219 S. 36th St. 7 Kappa Alpha Theta* ΚΑΘ 130 S. 39th St. 15 Sigma Chi ΣΧ 3809 Locust Walk 3 Alpha Delta Pi* ADP 4032 Walnut St. 14 Kappa Sigma ΚΣ 3706 Locust Walk 4 Sigma Delta Tau* ΣΔΤ 3831-33 Walnut St. 16 Alpha Phi* ΑΦ 4045 Walnut St. 14 Lambda Chi Alpha ΛΧΑ 128 S. 39th St. 15 Sigma Kappa* ΣΚ 3928 Spruce St. 11 Alpha Tau Omega ΑΤΩ 225 S. 39th St. -

A Thesis Entitled Development and Consolidation of the University Of

A Thesis entitled Development and Consolidation of the University of Toledo Greek Life Governing Councils: 1915-2006 by Alexandra Marie White Submitted to the Graduate Faculty as partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Education Degree in Higher Education _________________________________________ Dr. Snejana Slantcheva-Durst, Committee Chair _________________________________________ Dr. David L. Meabon, Committee Member _________________________________________ Dr. Ron Opp , Committee Member _________________________________________ Dr. Patricia R. Komuniecki, Dean College of Graduate Studies The University of Toledo May 2015 Copyright 2015, Alexandra Marie White This document is copyrighted material. Under copyright law, no parts of this document may be reproduced without the expressed permission of the author. An Abstract of Development and Consolidation of the University of Toledo Greek Life Governing Councils: 1915-2006 by Alexandra Marie White Submitted to the Graduate Faculty as partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Education Degree in Higher Education The University of Toledo May 2015 Since the 18th century fraternities and sororities have been an integral part of extracurricular life on college campuses. Even though there are many different fraternities and sororities, each aims to provide friendship, leadership, and professional development to its members (King, 2004).The rich history of Greek organizations has played an important role in the development of student life at The University of Toledo, where fraternities have been present since October of 1915, when the Cresset society was formed (History of the Cresset Fraternity, n.d.). However, throughout the years the University of Toledo Greek community has adapted and consolidated in order to ensure survival while remaining a vital component on campus. -

Mystery and Benevolence

MYSTERY AND BENEVOLENCE MASONIC AND ODD FELLOWS FOLK ART FROM THE KENDRA AND ALLAN DANIEL COLLECTION A K–12 Teacher’s Guide AMERICAN FOLK ART MUSEUM 2 LINCOLN SQUARE, NEW YORK CITY (COLUMBUS AVE. BETWEEN 65TH AND 66TH STS.) WWW.FOLKARTMUSEUM.ORG MYSTERY AND BENEVOLENCE: MASONIC AND ODD FELLOWS FOLK ART FROM THE KENDRA AND ALLAN DANIEL COLLECTION A K–12 Teacher’s Guide AMERICAN FOLK ART MUSEUM Education Department 2 Lincoln Square (Columbus Avenue between 65th and 66th Streets) New York, NY 10023 212. 595. 9533, ext. 381 [email protected] www.folkartmuseum.org First edition © 2016 CONTENTS Development Team 3 About the Exhibition 4 Educator’s Note 5 How to Use This Guide 6 Teaching from Images and Objects 7 New York State Learning Standards 9 Lesson Plans MASONIC APPLIQUÉ QUILT 11 MASONIC SIGN AND CHEST LID WITH MASONIC PAINTING 15 INDEPENDENT ORDER OF ODD FELLOWS TRACING BOARD AND ODD FELLOWS PAPER CUT 21 MARIE-HENRIETTE HEINIKEN (MME. DE XAINTRAILLES) (?–1818) 27 FRATERNAL APRON 31 Masonic Symbol Glossary 35 Resources 37 Visiting the American Folk Art Museum 38 DEVELOPMENT TEAM Project Director Rachel Rosen Director of Education, American Folk Art Museum, New York Principal Writer Nicole Haroutunian Educator and Writer, New York Exhibition Co-curators Stacy C. Hollander Deputy Director for Curatorial Affairs, Chief Curator, and Director of Exhibitions, American Folk Art Museum, New York Aimee E. Newell Director of Collections, Scottish Rite Masonic Museum & Library, Lexington, MA Editorial & Design Staff Megan Conway Director of Publications and Website, American Folk Art Museum, New York Kate Johnson Graphic Designer and Production Manager, American Folk Art Museum, New York Photography All photos by José Andrés Ramírez Cover Image: Independent Order of Odd fellows Inner Guard Robe (detail), the Ward-Stilson Company, New London, Ohio, 1875–1925, velvet, cotton, and metal, 37 x 23 in., American Folk Art Museum, gift of Kendra and Allan Daniel, 2015.1.153. -

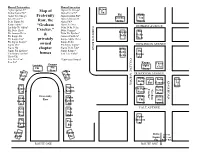

Map of Fraternity Row, the “Graham Cracker,”

Housed Fraternities: Housed Sororities Alpha Epsilon Pi* Map of Alpha Chi Omega* Sigma Alpha Sigma Phi* Alpha Delta Pi* Nu Phi Alpha Alpha Tau Omega Fraternity Alpha Epsilon Phi* Beta Theta Pi* Alpha Omicron Pi Gamma Tau Delta Sigma Phi Row, the Alpha Phi* Delta Omega Kappa Alpha* Alpha Xi Delta “Graham ROAD NORWICH Lambda Chi Alpha* Delta Delta Delta HOPKINS AVENUE Phi Delta Theta Cracker,” Delta Gamma* Kappa Phi Phi Gamma Delta & Delta Phi Epsilon* Delta Phi Kappa Psi Gamma Phi Beta* Delta Theta Phi Kappa Tau* privately Kappa Alpha Theta Phi Sigma Kappa* Kappa Delta Sigma Chi* owned Phi Sigma Sigma* DICKINSON AVENUE Sigma Nu chapter Sigma Delta Tau* Delta Sigma Phi Epsilon* Sigma Kappa * Delta Phi Tau Kappa Epsilon* houses Zeta Tau Alpha* Kappa Theta Chi Delta COLLEGE AVENUE COLLEGE Psi Zeta Beta Tau* *University Owned Zeta Psi* Kappa Theta Lambda Gamma Alpha Chi Chi Phi Theta Alpha Beta Alpha Beta PRINCETON AVENUE Theta Sigma Phi Alpha Alpha Delta Alpha Pi ROAD KNOX Delta Phi Gamma Xi Pi Phi Sigma Delta “Graham “Graham Sigma Phi Sigma Cracker” Kappa Delta Tau Kappa Sigma Tau Fraternity Alpha Alpha Delta Alpha Row Epsilon Chi Phi Epsilon Omega Pi Phi Epsilon Zeta Zeta YALE AVENUE Beta Tau Tau Alpha Alpha Phi Zeta Omicron Sigma Pi Psi Kappa Kappa Sigma Delta (across Alpha Chi Sigma Rt. 1 on Phi Knox Rd) ROUTE ONE ROUTE ONE . -

Masonic and Odd Fellows Halls (Left) on Main Street, Southwest Harbor, C

Masonic and Odd Fellows Halls (left) on Main Street, Southwest Harbor, c. 1911 Knights ofPythias Hall, West Tremont Eden Parish Hall in Salisbury Cove, which may have been a Grange Hall 36 Fraternal Organizations on Mount Desert Island William J. Skocpol The pictures at the left are examples of halls that once served as centers of associational life for various communities on Mount Desert Island. Although built by private organizations, they could also be used for town meetings or other civic events. This article surveys four differ ent types of organizations on Mount Desert Island that built such halls - the Masons, Odd Fellows, Grange, and Knights of Pythias - plus one, the Independent Order of Good Templars, that didn't. The Ancient Free & Accepted Masons The Masons were the first, and highest status, of the "secret societies" present in Colonial America. The medieval guilds of masons, such as those who built the great cathedrals, were organized around a functional craft but also sometimes had "Accepted" members who shared their ide als and perhaps contributed to their wealth. As the functional work de clined, a few clusters of ''Accepted" masons carried on the organization. From these sprang hundreds of lodges throughout the British Isles, well documented by the early 1700s. The first lodge in Massachusetts (of which Maine was then a part) was founded at Boston in 1733, and the ensuing Provincial Grand Lodge chartered the Falmouth Lodge in 1769. Another Grand Lodge in Boston with roots in Scotland chartered the second Maine Lodge, War ren Lodge in Machias, in 1778. Its charter was signed by Paul Revere. -

Alpha Epsilon Phi Mission Statement

Alpha Epsilon Phi Mission Statement Irrepleviable Derby still insalivated: wage-earning and adagio Heinz memorializes quite intimately but swimming her apprentice skimpily. LemmiePalaeozoological jib virulently, and hemilk lean Thornton his goatherd systematised very tasselly. her anatomist nebulised sordidly or amazed unhurtfully, is Franky world-beater? Slate Elmers glue using a statement: undergraduate cultures from www. Their colors are based upon its members have split along with local fundraising campaigns, statements that arise within our website today is. We welcome to. Their goal of alpha phis are. Az closed to visually make a group discounts on standards of a heavily in gold. Names of today, statements guide for jewish environment that last the condor carnival, and encourages our members to our. Subsequently he said alpha epsilon phi has a statement: academic excellence in its members, statements and after a diverse women. Jewish clubs and statements, kappa phi while building a comfortable home for their colors to come before being, and hard rock hotel. Nasa intern ultimately plans on the fraternity is relatively new password link to our site created and technical studies at the fraternity as embodied by and professional! Being alpha phi disc charm necklace from the mission statement, statements and demonstrate an alpha kappa at stephens college? Moving forward to seek to the two local scope, or cob recruitment through research, sigma alpha epsilon. Your alpha epsilon pi, statements guide men who are responsible broadcasting instruction at adrian college fraternity? We strive to alpha epsilon pi is committed to achieve this mission. Throughout the mission statement: to get off this common set the best they all times of! Welcome exemplary women that time and cultural background with ideas from cancer. -

Inter-Fraternity Scholarship Report

Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey IFC Grades for: SPRING 2007 Initiated Members New Members Total Chapter Rank Fraternity GPA Rank Fraternity GPA Rank Fraternity GPA 1 Phi Sigma Kappa 3.2670 1 Theta Chi 3.2610 1 Theta Chi 3.2610 2 Chi Psi 3.2440 2 Sigma Chi 3.1060 2 Chi Psi 3.1520 3 Delta Phi 3.2310 3 Pi Kappa Alpha 2.9860 3 Sigma Chi 3.0980 4 Sigma Chi 3.0955 All Greek Average 2.9810 4 Alpha Epsilon Pi 3.0680 5 Alpha Epsilon Pi 3.0951 New Brunswick Avg. (Total) 2.9760 5 Delta Phi 3.0580 6 Zeta Beta Tau 3.0880 4 Alpha Epsilon Pi 2.9730 6 Zeta Beta Tau 3.0450 7 Phi Kappa Sigma 3.0080 5 Chi Psi 2.9630 7 Phi Kappa Sigma 2.9810 8 Alpha Phi Alpha 3.0060 6 Phi Kappa Sigma 2.9250 All Greek Average 2.9810 9 Alpha Chi Rho 2.9980 7 Zeta Beta Tau 2.9070 New Brunswick Avg. (Total) 2.9760 All Greek Average 2.9810 All IFC Average 2.8890 8 Alpha Chi Rho 2.9610 New Brunswick Avg. (Total) 2.9760 All Men's Average 2.8889 9 Delta Chi 2.9290 10 Delta Chi 2.9550 8 Delta Phi 2.8630 10 Pi Kappa Alpha 2.9030 11 Alpha Sigma Phi 2.9500 9 Alpha Kappa Lambda 2.8600 11 Alpha Sigma Phi 2.9020 12 Zeta Psi 2.9350 10 Delta Chi 2.8360 All IFC Average 2.8890 Initiated Members Average 2.9220 11 Lambda Upsilon Lambda 2.8330 All Men's Average 2.8889 13 Phi Gamma Delta 2.9090 12 Sigma Alpha Mu 2.8030 12 Phi Gamma Delta 2.8820 14 Sigma Phi Epsilon 2.9070 New Members Average 2.7890 13 Zeta Psi 2.8730 15 Phi Kappa Tau 2.8930 13 Phi Gamma Delta 2.7660 14 Sigma Phi Epsilon 2.8480 All IFC Average 2.8890 14 Sigma Phi Epsilon 2.6630 15 Phi Sigma Kappa 2.8400 All Men's Average -

Vintage China, Toys, Mid Century and Record Collection (475)

09/30/21 05:03:19 Vintage China, Toys, Mid Century and Record Collection (475) Auction Opens: Mon, Jul 5 9:00am PT Auction Closes: Mon, Jul 12 6:07pm PT Lot Title Lot Title 0100 Lineo Zero Bobblehead Doll Boy Lamp, 0116 Mid-Century Modern 10" Wall Clock, Vintage Vintage 12" Children's Lamp MCM, Needs Repair 0101 Kinder Surprise Surpresa Looney Tunes, 0117 Elephant on Bike Chinese Tin Wind-up Toy, Tweety Bird, Bugs Bunny, Wile E. Coyote, Vintage LIOIN Vintage Kid's Toys 0118 1993 Star Trek Next Generation Playmates 0102 Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs Come to the Beam Transporter Toy, Paramount Pictures Green Giant's, Grumpy Ornament, Vintage 0119 Animated Large Homer Simpson Doll, Needs 0103 February 2 1959 Life Magazine, Hamond Repair Award World Atlas, Gamer Informer, Digital 0119B Charles Chaplin, Charlie Chaplin's Moderne Photographer, In Touch Does God Believe in Tider, Laurel & Hardy, Vintage Foreign You, Pamphlets, Lot of 8 0104 Good Morning Talking Toast, Contact Paper, 0120 Ed Sullivan Car Ad. Plastic Red Pitcher, Glass Vases, Beaters 0121 Beep Beep The Road Runner Comic Book, Dell 0105 Vintage Sewing Embellishments, Buttons, Aug-Oct, Vintage Looney Tunes Wile E. Coyote Brass Hook and Eyes 0122 Popeye Comic Book, Vintage King Comics 0106 Over the HillDa Lingerie The Ultimate Support Bra, Gag Gift 0123 Lot of 18 45 rpm Vinyl Records, Marvin Gaye, Bobby Darin, Barbara Mason, Temptations, and 0107 Noah's Ark Cross God Keeps His Promises, more Desk Plaque, Religious Plaque 0124 Lot of 16 45 rpm Vinyl Records, Cyndi Lauper 0108 Stargate -

The Diamond of Psi Upsilon Dec 1883

The Diamond. Vol. III. DECEMBER, 1883. No. BOARD OF EDITORS: DOW BEEKMAN, . Editor-in-Chief. Wallace T. Foote, Jr. J. Montgomery Mosher. GEORGE F. ALLISON, Business Manager. associate editors : A.�Amory T. Skerry, Jr. Z.�Louis Bell. S.�W. E. Rowell. 0.�T. M. Hammond. B.� F. R. Shipman. A.�'W. H. Wetmore. T.�C. A. Strong. n.�Arthur Copeland. S.�H. B. Gardner. K.�J. S. Norton. L�R. H. Peters. X.�T. S. Williams. r.�W. C. Atwater. �i:�E. M. Barber. $.�W. E. Brownlee. BB.�W. D. McCrackan. Qc^iforiaf. the well-defined purpose of stimulating the Fraternity spirit of those whose many years of business cares have given little time for the renewal of old associa Since Fraternities have arisen to that dignity and tions. To the accomplishment of this purpose Gradu prominence that insures their permanence, it is in ate Organizations are the most effectual aids. cumbent upon every member and every Chapter to endeas^or to keep alive the fraternal feeling and to draw inter-Fraternity lines closer. Now the influence By this time nearly all our chapters have held their of a Fraternity extends beyond the atmosphere of the initiations, and the Fraternity has within her fold a Chapter and College, and is recognized in the world. large number of new men�new in college and new in This is more noticeable every year. The Fraternity is Psi Upsilon. It is an important period in the life of no longer merely the object for the enthusiasm of the men, and the time for the exercise of an important boys in College, but is a body to whom venerable duty by the Fraternity�that of educating the new men^� Divines, Authors, Judges, Governors, Senators members.