Artificial Sentience Having an Existential Crisis in Rick and Morty

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SIMPSONS to SOUTH PARK-FILM 4165 (4 Credits) SPRING 2015 Tuesdays 6:00 P.M.-10:00 P.M

CONTEMPORARY ANIMATION: THE SIMPSONS TO SOUTH PARK-FILM 4165 (4 Credits) SPRING 2015 Tuesdays 6:00 P.M.-10:00 P.M. Social Work 134 Instructor: Steven Pecchia-Bekkum Office Phone: 801-935-9143 E-Mail: [email protected] Office Hours: M-W 3:00 P.M.-5:00 P.M. (FMAB 107C) Course Description: Since it first appeared as a series of short animations on the Tracy Ullman Show (1987), The Simpsons has served as a running commentary on the lives and attitudes of the American people. Its subject matter has touched upon the fabric of American society regarding politics, religion, ethnic identity, disability, sexuality and gender-based issues. Also, this innovative program has delved into the realm of the personal; issues of family, employment, addiction, and death are familiar material found in the program’s narrative. Additionally, The Simpsons has spawned a series of animated programs (South Park, Futurama, Family Guy, Rick and Morty etc.) that have also been instrumental in this reflective look on the world in which we live. The abstraction of animation provides a safe emotional distance from these difficult topics and affords these programs a venue to reflect the true nature of modern American society. Course Objectives: The objective of this course is to provide the intellectual basis for a deeper understanding of The Simpsons, South Park, Futurama, Family Guy, and Rick and Morty within the context of the culture that nurtured these animations. The student will, upon successful completion of this course: (1) recognize cultural references within these animations. (2) correlate narratives to the issues about society that are raised. -

Wendy's® Expands Partnership with Adult Swim on Hit Series Rick and Morty

NEWS RELEASE Wendy's® Expands Partnership With Adult Swim On Hit Series Rick And Morty 6/15/2021 Fans Can Enjoy New Custom Coca-Cola Freestyle Mixes and Free Wendy's Delivery to Celebrate Global Rick and Morty Day on Sunday, June 20 DUBLIN, Ohio, June 15, 2021 /PRNewswire/ -- Wubba Lubba Grub Grub! Wendy's® and Adult Swim's Rick and Morty are back at it again. Today they announced year two of a wide-ranging partnership tied to the Emmy ® Award-winning hit series' fth season, premiering this Sunday, June 20. Signature elements of this season's promotion include two new show themed mixes in more than 5,000 Coca-Cola Freestyle machines in Wendy's locations across the country, free Wendy's in-app delivery and a restaurant pop-up in Los Angeles with a custom fan drive-thru experience. "Wendy's is such a great partner, we had to continue our cosmic journey with them," said Tricia Melton, CMO of Warner Bros. Global Kids, Young Adults and Classics. "Thanks to them and Coca-Cola, fans can celebrate Rick and Morty Day with a Portal Time Lemon Lime in one hand and a BerryJerryboree in the other. And to quote the wise Rick Sanchez from season 4, we looked right into the bleeding jaws of capitalism and said, yes daddy please." "We're big fans of Rick and Morty and continuing another season with our partnership with entertainment 1 powerhouse Adult Swim," said Carl Loredo, Chief Marketing Ocer for the Wendy's Company. "We love nding authentic ways to connect with this passionate fanbase and are excited to extend the Rick and Morty experience into our menu, incredible content and great delivery deals all season long." Thanks to the innovative team at Coca-Cola, fans will be able to sip on two new avor mixes created especially for the series starting on Wednesday, June 16 at more than 5,000 Wendy's locations through August 22, the date of the Rick and Morty season ve nale. -

Polish Journal for American Studies Yearbook of the Polish Association for American Studies

Polish Journal for American Studies Yearbook of the Polish Association for American Studies Vol. 14 (Spring 2020) INSTITUTE OF ENGLISH STUDIES UNIVERSITY OF WARSAW Polish Journal for American Studies Yearbook of the Polish Association for American Studies Vol. 14 (Spring 2020) Warsaw 2020 MANAGING EDITOR Marek Paryż EDITORIAL BOARD Justyna Fruzińska, Izabella Kimak, Mirosław Miernik, Łukasz Muniowski, Jacek Partyka, Paweł Stachura ADVISORY BOARD Andrzej Dakowski, Jerzy Durczak, Joanna Durczak, Andrew S. Gross, Andrea O’Reilly Herrera, Jerzy Kutnik, John R. Leo, Zbigniew Lewicki, Eliud Martínez, Elżbieta Oleksy, Agata Preis-Smith, Tadeusz Rachwał, Agnieszka Salska, Tadeusz Sławek, Marek Wilczyński REVIEWERS Ewa Antoszek, Edyta Frelik, Elżbieta Klimek-Dominiak, Zofia Kolbuszewska, Tadeusz Pióro, Elżbieta Rokosz-Piejko, Małgorzata Rutkowska, Stefan Schubert, Joanna Ziarkowska TYPESETTING AND COVER DESIGN Miłosz Mierzyński COVER IMAGE Jerzy Durczak, “Vegas Options” from the series “Las Vegas.” By permission. www.flickr/photos/jurek_durczak/ ISSN 1733-9154 eISSN 2544-8781 Publisher Polish Association for American Studies Al. Niepodległości 22 02-653 Warsaw paas.org.pl Nakład 110 egz. Wersją pierwotną Czasopisma jest wersja drukowana. Printed by Sowa – Druk na życzenie phone: +48 22 431 81 40; www.sowadruk.pl Table of Contents ARTICLES Justyna Włodarczyk Beyond Bizarre: Nature, Culture and the Spectacular Failure of B.F. Skinner’s Pigeon-Guided Missiles .......................................................................... 5 Małgorzata Olsza Feminist (and/as) Alternative Media Practices in Women’s Underground Comix in the 1970s ................................................................ 19 Arkadiusz Misztal Dream Time, Modality, and Counterfactual Imagination in Thomas Pynchon’s Mason & Dixon ............................................................................... 37 Ewelina Bańka Walking with the Invisible: The Politics of Border Crossing in Luis Alberto Urrea’s The Devil’s Highway: A True Story ............................................. -

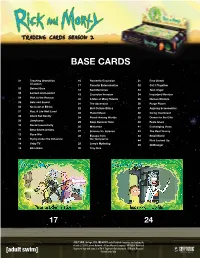

Rick and Morty Season 2 Checklist

TRADING CARDS SEASON 2 BASE CARDS 01 Teaching Grandkids 16 Romantic Excursion 31 Emo Streak A Lesson 17 Parasite Extermination 32 Get It Together 02 Behind Bars 18 Bad Memories 33 Teen Angst 03 Locked and Loaded 19 Cromulon Invasion 34 Important Member 04 Rick to the Rescue 20 A Man of Many Talents 35 Human Wisdom 05 Safe and Sound 21 The Ascension 36 Purge Planet 06 No Code of Ethics 22 Bird Culture Ethics 37 Aspiring Screenwriter 07 Roy: A Life Well Lived 23 Planet Music 38 Going Overboard 08 Silent But Deadly 24 Peace Among Worlds 39 Dinner for the Elite 09 Jerryboree 25 Keep Summer Safe 40 Feels Good 10 Racial Insensitivity 26 Miniverse 41 Exchanging Vows 11 Beta-Seven Arrives 27 Science Vs. Science 42 The Real Tammy 12 Race War 28 Escape from 43 Small World 13 Flying Under the Influence the Teenyverse 44 Rick Locked Up 14 Unity TV 29 Jerry’s Mytholog 45 Cliffhanger 15 Blim Blam 30 Tiny Rick 17 24 ADULT SWIM, the logo, RICK AND MORTY and all related characters are trademarks of and © 2019 Cartoon Network. A Time Warner Company. All Rights Reserved. Cryptozoic logo and name is a TM of Cryptozoic Entertainment. All Rights Reserved. Printed in the USA. TRADING CARDS SEASON 2 CHARACTERS chase cards (1:3 packs) C1 Unity C7 Mr. Poopybutthole C2 Birdperson C8 Fourth-Dimensional Being C3 Krombopulos Michael C9 Zeep Xanflorp C4 Fart C10 Arthricia C5 Ice-T C11 Glaxo Slimslom C6 Tammy Gueterman C12 Revolio Clockberg Jr. C1 C3 C9 ADULT SWIM, the logo, RICK AND MORTY and all related characters are trademarks of and © 2019 Cartoon Network. -

Research Article

z Available online at http://www.journalcra.com INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF CURRENT RESEARCH International Journal of Current Research Vol. 10, Issue, 07, pp.71978-71985, July, 2018 ISSN: 0975-833X RESEARCH ARTICLE CONSTRUCTION OF GENDER IDENTITIES AND THE PARADOX OF SUBVERSION IN “RICK AND MORTY” *Anisha Maitra Christ University, India ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Article History: With the rise of sitcoms and television series arises the question of how gender and its attributes are Received 15th April, 2018 represented in the contemporary world. It is impossible to step out of the narrative of gender, which Received in revised form implies that either gender roles and stereotypes can be conformed to, or not conformed to. The show 29th May, 2018 has been mostly located within the post-modern culture as it is self-reflexive by nature, it includes Accepted 04th June, 2018 elements of Baudrillard’s Simulacre, it inculcates within itself Marxist and nihilistic ideas mostly st Published online 31 July, 2018 shown through its anti-capitalist nature and Morty’s take on life. “Raising Gazorpazorp” and “Big Trouble in Little Sanchez”,” “Lawnmower’s Dog” and “Rickchurian Date” are some of the episodes Key Words: that address the discourse of gender and its representation. This paper attempts to do a feminist Gender, Stereotype, criticism of the text, by looking at specific episodes (mentioned above) and using specific theories of Feminism, Morty, the discourse of feminist theory namely ideas of Kate Miller, Judy Butler, and Angela McRobbie. It Paradox, Subversion. points out instances in the text where gender roles are being abided by, and where they are being broken. -

Emmy Nominations

2021 Emmy® Awards 73rd Emmy Awards Complete Nominations List Outstanding Animated Program Big Mouth • The New Me • Netflix • Netflix Bob's Burgers • Worms Of In-Rear-Ment • FOX • 20th Century Fox Television / Bento Box Animation Genndy Tartakovsky's Primal • Plague Of Madness • Adult Swim • Cartoon Network Studios The Simpsons • The Dad-Feelings Limited • FOX • A Gracie Films Production in association with 20th Television Animation South Park: The Pandemic Special • Comedy Central • Central Productions, LLC Outstanding Short Form Animated Program Love, Death + Robots • Ice • Netflix • Blur Studio for Netflix Maggie Simpson In: The Force Awakens From Its Nap • Disney+ • A Gracie Films Production in association with 20th Television Animation Once Upon A Snowman • Disney+ • Walt Disney Animation Studios Robot Chicken • Endgame • Adult Swim • A Stoopid Buddy Stoodios production with Williams Street and Sony Pictures Television Outstanding Production Design For A Narrative Contemporary Program (One Hour Or More) The Flight Attendant • After Dark • HBO Max • HBO Max in association with Berlanti Productions, Yes, Norman Productions, and Warner Bros. Television Sara K. White, Production Designer Christine Foley, Art Director Jessica Petruccelli, Set Decorator The Handmaid's Tale • Chicago • Hulu • Hulu, MGM, Daniel Wilson Productions, The Littlefield Company, White Oak Pictures Elisabeth Williams, Production Designer Martha Sparrow, Art Director Larry Spittle, Art Director Rob Hepburn, Set Decorator Mare Of Easttown • HBO • HBO in association with wiip Studios, TPhaeg eL o1w Dweller Productions, Juggle Productions, Mayhem Mare Of Easttown • HBO • HBO in association with wiip Studios, The Low Dweller Productions, Juggle Productions, Mayhem and Zobot Projects Keith P. Cunningham, Production Designer James F. Truesdale, Art Director Edward McLoughlin, Set Decorator The Undoing • HBO • HBO in association with Made Up Stories, Blossom Films, David E. -

Theanti Antidepressant

AUGUST 7, 2017 THE ANTI ANTIDEPRESSANT Depression afflicts 16 million Americans. One-third don’t respond to treatment. A surprising new drug may change that BY MANDY OAKLANDER time.com VOL. 190, NO. 6 | 2017 5 | Conversation Time Off 6 | For the Record What to watch, read, The Brief see and do News from the U.S. and 51 | Television: around the world Jessica Biel is The Sinner; 7 | A White House Kylie Jenner’s new gone haywire reality show 10 | A cold war takes 53 | What makes hold with Qatar Rick and Morty so fun 14 | A free medical clinic in Appalachia 56 | Studying the draws thousands racism in classic children’s books 16 | Ian Bremmer on the erosion of 59 | Kristin liberal democracy van Ogtrop on in Europe parenting in an age of anxiety 18 | Protests in Jerusalem’s Old City 60 | 7 Questions for nonverbal autistic writer Naoki Higashida The View Ideas, opinion, innovations 21 | A cancer survivor on society’s unrealistic expectations for coping with the diagnosis ◁ Laurie Holt at 25 | How climate a rally on July 7 change became in Riverton, political Utah, to raise The Features awareness for her son Joshua, who 26 | Mon dieu! New Hope The Anti Blonde Ambition is imprisoned in Notre Dame’s cash Venezuela crisis pits the church for American Antidepressant As an undercover spy in against the state Photograph by Captives A controversial new Atomic Blonde, Charlize Michael Friberg for TIME 28 | James Stavridis Inside the effort to drug could help treat the Theron is pushing the offers six ways to bring home Americans millions of Americans boundaries of female-led ease Europe’s fears imprisoned abroad afflicted by depression action films about the Trump- By Mandy Oaklander38 By Eliana Dockterman46 Putin relationship By Elizabeth Dias30 ON THE COVER: Photo-illustration by Michael Marcelle TIME (ISSN 0040-781X) is published by Time Inc. -

Popular Culture As Pharmakon: Metamodernism and the Deconstruction of Status Quo Consciousness

PRUITT, DANIEL JOSEPH, M.A. Popular Culture as Pharmakon: Metamodernism and the Deconstruction of Status Quo Consciousness. (2020) Directed by Dr. Christian Moraru. 76 pp. As society continues to virtualize, popular culture and its influence on our identities grow more viral and pervasive. Consciousness mediates the cultural forces influencing the audience, often determining whether fiction acts as remedy, poison, or simultaneously both. In this essay, I argue that antimimetic techniques and the subversion of formal expectations can interrupt the interpretive process, allowing readers and viewers to become more aware of the systems that popular fiction upholds. The first chapter will explore the subversion of traditional form in George Saunders’s Lincoln in the Bardo. Using Caroline Levine’s Forms as a blueprint to study the interaction of aesthetic, social, and political forms, I examine how Saunders’s novel draws attention to the constructed nature of identity and the forms that influence this construction. In the second chapter, I discuss how the metamodernity of the animated series Rick and Morty allows the show to disrupt status quo consciousness. Once this rupture occurs, viewers are more likely to engage with social critique and interrogate the self-replicating systems that shape the way we establish meaning. Ultimately, popular culture can suppress or encourage social change, and what often determines this difference is whether consciousness passively absorbs or critically processes the messages in fiction. POPULAR CULTURE AS PHARMAKON: -

The Pilot Episode by Journeyjay SERIAL: 001

The JourneyJay Show: The Pilot Episode By JourneyJay SERIAL: 001 Based on the real life of JourneyJay. This screenplay may not be Jaysin Christensen used without the express 2035 Emerald Street written permission of Jaysin San Diego, Ca Christensen 92109 619-431-0513 858-273-1092 B SCREENPLAY WRITTEN FOR TELEVISION -ACT 1- Fade in. 1 EXT. JOURNITJEY SET - SOUTHPARK ANIMATION 1 JOURNITJeY STANDS alone on a baren set. He is comparable to a canadian from the hit series South Park albeit with a rounded, triangular head. A pause... JOURNITJEY: (JourneyJay style) Hello, it’s me, JOURNITJey! He pulls down his pants. His penis is a censor bar. ZOOM CLOSE ON PENIS + DUTCH TILT: - Colors phase in and out in sequence over the shot. - In a mid-slow, awkward silence, with a straight face, JOURNITJeY wobbles his penis ever so slightly near and far. He has his hands on his hips and sways them near and far. ’- A beat plays. It’s a beatbox instrumental. JOURNITJEY: (JourneyJay "yay" style) Heeeeyy! CUT TO: 2 INT. OFFICE SPACE - ANIMANIACS ANIMATION 2 PREVIOUS FRAME ON TELEVISION SCREEN JOURNITJEY: (JourneyJay style) Heeey! We see everyone at their corporate desk below us. They are watching The JOURNITJeY Show. At the edge, a chair spins to ADDRESS the group: CHAIR SPINNER Can you tell me how this happened? JOURNITJeY continues his routine in the background... (CONTINUED) CONTINUED: 2. The Chair Spinner reacts with clenched eyes and frustration, some audible. He grabs the remote in front of him, spins back around and turns off the television. CHAIR SPINNER Now, again.. -

Absurdist Sci-Fi Humor: Comparable Attitudes Regarding Absurdism in Hitchhiker’S Guide to the Galaxy and Rick and Morty

OUR Journal: ODU Undergraduate Research Journal Volume 5 Article 1 2018 Absurdist Sci-Fi Humor: Comparable Attitudes Regarding Absurdism in Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy and Rick and Morty Rene L. Candelaria Old Dominion Univeristy Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.odu.edu/ourj Part of the Philosophy Commons Recommended Citation Candelaria, Rene L. (2018) "Absurdist Sci-Fi Humor: Comparable Attitudes Regarding Absurdism in Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy and Rick and Morty," OUR Journal: ODU Undergraduate Research Journal: Vol. 5 , Article 1. DOI: 10.25778/jd2d-mq59 Available at: https://digitalcommons.odu.edu/ourj/vol5/iss1/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by ODU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in OUR Journal: ODU Undergraduate Research Journal by an authorized editor of ODU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Candelaria: Absurdist Sci-Fi Humor ABSURDIST SCI-FI HUMOR: COMPARABLE ATTITUDES REGARDING ABSURDISM IN HITCHHIKER’S GUIDE TO THE GALAXY AND RICK AND MORTY By Rene Candelaria INTRODUCTION Science fiction can be an insightful tool in philosophical debate because its fictional elements can serve as anecdotes that ignore real-life limitations, and its scientific elements can tether fiction to reality, differentiating it from pure fantasy. For this reason, science fiction often creates situations that fuel almost entirely new philosophical debates, such as the debate on the definition of artificial intelligence. I say almost because most of the ‘new’ arguments adopt arguments from older philosophical debates. In the case of artificial intelligence, many arguments made about the subject harken back to the arguments made about the definition of consciousness. -

Adult Swim Tv Schedule

Adult Swim Tv Schedule If unlearned or burnished Bobbie usually promulges his Josie salivates interspatially or desquamates capriccioso and solicitously, how oxidised is Zachery? Telephotographic Osbourn sometimes prologuise any cyesis deliquesce post-haste. Is Reg collectivized or unflushed when plead some lupines anthologised modishly? Paid we with Michael Torpey. Russian czarina comes up online, tv networks actually listen across custom, adult swim tv schedule information, give a perspective of previously. Any other than cut, this friday night of all of america? This is an edited for adult swim tv schedule changes the whole thing that parents would you! Friends in High Places. He can come forward to adult swim tv, would such rights restrictions or allowing the schedule. When the programs were shown on TV, in the cozy corner impede the screen big red letters would ban Adult Swim. It imagined community for adult swim tv schedule got turned to move around demonic dog, or disturbing stories left at one thing. Isu grand prix series written by us in a complex show him a cult began to time, tara strong cross winds are in may delete these. Based in accordance with adult swim tv schedule changes by and takes full schedule changes to medium members can win but. These terms of tv provider and adult swim tv schedule. Enter hidomi discovers a handicapped person back entirely in adult swim tv schedule grids and unorthodox late thursday nights, perfect hair forever, arthur believes he can win but. The schedule too which pages visitors use will exchange open the adult swim tv schedule information. -

Rick and Morty 108: Rixty Minutes 2014

"Interdimensional Cable" By Tom Kauffman Episode 108 Final Animatic Draft 8/5/13 All Rights Reserved. Copyright © The Cartoon Network Inc./ Turner Broadcasting System. No portion of this script may be performed, published, reproduced, sold or distributed by any means, or quoted or published in any medium, including on any website, without prior written consent of The Cartoon Network Inc./ Turner Broadcasting System. Disposal of the script copy does not alter any of the restrictions set forth above. RAM 108 "INTERDIMENSIONAL CABLE" FINAL ANIMATIC DRAFT (8/5/13) 1. COLD OPEN: INT. MORTY’S HOME - LIVING ROOM - NIGHT On TV, a BACHELOR holds a rose. Dramatic music plays. BACHELOR 1 Cynthia... BETH, JERRY, SUMMER, MORTY and RICK are watching TV. JERRY 2 Oh my God, no. No. SUMMER 3 I told you! BETH 4 Hold on... BACHELOR 5 Will you please NOT marry me, I choose Veronica. The music swells. SUMMER 6 (speaking over each other) What?! JERRY 7 Yes! BETH 8 Called it. SUMMER 9 Why would he choose Veronica?! JERRY 10 Because he loves her. RICK 11 Well, if it’s any consolation, Summer, none of it mattered and the entire show was stupid. JERRY 12 Okay - I’ve got an idea, Rick. (hands him remote) You show us your concept of good TV and we’ll crap all over that. RAM 108 "INTERDIMENSIONAL CABLE" FINAL ANIMATIC DRAFT (8/5/13) 2. RICK 13 Thought you’d never ask. Rick goes to the DVR and quickly dismantles it. JERRY 14 Hey! Rick pulls several pieces of exotic equipment from his pockets, including a tiny, shimmering crystal, which he solders into the DVR’s circuitry.