Representations of Abortion in Adult Animated Television Comedy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The 26Th Society for Animation Studies Annual Conference Toronto

Sheridan College SOURCE: Sheridan Scholarly Output, Research, and Creative Excellence The Animator Conferences & Events 6-16-2014 The Animator: The 26th oS ciety for Animation Studies Annual Conference Toronto June 16 to 19, 2014 Society for Animation Studies Paul Ward Society for Animation Studies Tony Tarantini Sheridan College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://source.sheridancollege.ca/conferences_anim Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons SOURCE Citation Society for Animation Studies; Ward, Paul; and Tarantini, Tony, "The Animator: The 26th ocS iety for Animation Studies Annual Conference Toronto June 16 to 19, 2014" (2014). The Animator. 1. http://source.sheridancollege.ca/conferences_anim/1 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Conferences & Events at SOURCE: Sheridan Scholarly Output, Research, and Creative Excellence. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Animator by an authorized administrator of SOURCE: Sheridan Scholarly Output, Research, and Creative Excellence. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THANK YOU TO OUR SPONSORS THE ANIMATOR THEThe 26th Society forANIMATOR Animation Studies Annual Conference TheToronto 26 Juneth Society 16 to 19, 2014 for www.theAnimation animator2014.com Studies @AnimatorSAS2014 Annual Conference Toronto June 16 to 19, 2014 • www.the animator2014.com • @AnimatorSAS2014 WELCOME Message from the President Animation is both an art and skill; it is a talent that is envied the world over. Having a hand in educating and nurturing some of the finest animators in the world is something for which Sheridan is exceptionally proud. -

Here Comes Television

September 1997 Vol. 2 No.6 HereHere ComesComes TelevisionTelevision FallFall TVTV PrPrevieweview France’France’ss ExpandingExpanding ChannelsChannels SIGGRAPHSIGGRAPH ReviewReview KorKorea’ea’ss BoomBoom DinnerDinner withwith MTV’MTV’ss AbbyAbby TTerkuhleerkuhle andand CTW’CTW’ss ArleneArlene SherShermanman Table of Contents September 1997 Vol. 2, . No. 6 4 Editor’s Notebook Aah, television, our old friend. What madness the power of a child with a remote control instills in us... 6 Letters: [email protected] TELEVISION 8 A Conversation With:Arlene Sherman and Abby Terkuhle Mo Willems hosts a conversation over dinner with CTW’s Arlene Sherman and MTV’s Abby Terkuhle. What does this unlikely duo have in common? More than you would think! 15 CTW and MTV: Shorts of Influence The impact that CTW and MTV has had on one another, the industry and beyond is the subject of Chris Robinson’s in-depth investigation. 21 Tooning in the Fall Season A new splash of fresh programming is soon to hit the airwaves. In this pivotal year of FCC rulings and vertical integration, let’s see what has been produced. 26 Saturday Morning Bonanza:The New Crop for the Kiddies The incurable, couch potato Martha Day decides what she’s going to watch on Saturday mornings in the U.S. 29 Mushrooms After the Rain: France’s Children’s Channels As a crop of new children’s channels springs up in France, Marie-Agnès Bruneau depicts the new play- ers, in both the satellite and cable arenas, during these tumultuous times. A fierce competition is about to begin... 33 The Korean Animation Explosion Milt Vallas reports on Korea’s growth from humble beginnings to big business. -

2021 NASP® Bullseye National, Open & Championship Tournament Rules Iowa League and State Tournaments

2021 NASP® Bullseye National, Open & Championship Tournament Rules Iowa League and State Tournaments Registration dates & hotel information will be posted at www.naspschools.org under events Iowa State NASP Tournament: Des Moines, IA March 6-7, 2021 Western NASP® National: Sandy, UT, April 23-24, 2021 Eastern NASP® National: Louisville, KY, May 6-8, 2021 NASP® Open and Championship: Myrtle Beach, SC, June 10-12, 2021 The Archery Way Competing with Honesty and Integrity As archers, we strive to shoot our best while competing with integrity. Honesty is an expectation, sportsmanship and composure, an obligation. We encourage others and understand our responsibility to self-officiate and protect the field with an overall goal of bringing the archery way into everyday life. Table of Contents Rules specific to Iowa are noted in RED 1. NASP® Participation ...................................................................................................................................... 3 1.1. Definition of NASP® School ...................................................................................................................... 3 1.2. In School Requirement ............................................................................................................................ 4 1.3. Divisions within NASP® Schools: .............................................................................................................. 5 1.4. Eligible grades ...................................................................................................................................... -

View/Method……………………………………………………9

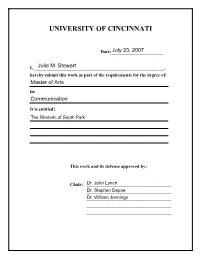

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date:___________________July 23, 2007 I, ________________________________________________Julie M. Stewart _________, hereby submit this work as part of the requirements for the degree of: Master of Arts in: Communication It is entitled: The Rhetoric of South Park This work and its defense approved by: Chair: _______________________________Dr. John Lynch _______________________________Dr. Stephen Depoe _______________________________Dr. William Jennings _______________________________ _______________________________ THE RHETORIC OF SOUTH PARK A thesis submitted to the Division of Graduate Studies and Research Of the University of Cincinnati MASTER OF ARTS In the Department of Communication, of the College of Arts and Sciences 2007 by Julie Stewart B.A. Xavier University, 2001 Committee Chair: Dr. John Lynch Abstract This study examines the rhetoric of the cartoon South Park. South Park is a popular culture artifact that deals with numerous contemporary social and political issues. A narrative analysis of nine episodes of the show finds multiple themes. First, South Park is successful in creating a polysemous political message that allows audiences with varying political ideologies to relate to the program. Second, South Park ’s universal appeal is in recurring populist themes that are anti-hypocrisy, anti-elitism, and anti- authority. Third, the narrative functions to develop these themes and characters, setting, and other elements of the plot are representative of different ideologies. Finally, this study concludes -

The Legacy of INTERPOL Crime Data to Cross-National Criminology1

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF COMPARATIVE AND APPLIED CRIMINAL JUSTICE FALL 2009, VOL. 33, NO. 2 The Legacy of INTERPOL Crime Data to Cross-National Criminology1 ROSEMARY BARBERET2 John Jay College of Criminal Justice, CUNY INTERPOL crime data constitute the oldest and most continuous cross-national data series available to criminologists. Recently, INTERPOL has decided to forego its data collection efforts. This paper, based on a systematic and extensive literature review, will examine how criminologists and other social scientists have used INTERPOL data to examine criti- cal issues in the description and explanation of cross-national crime. It will end with a critical reflection on the contribution of INTERPOL data to our knowledge base, as well as the possibilities that exist for using other data sources to continue research in this area. INTRODUCTION Crime data from INTERPOL are the oldest dataset of cross-national indica- tors of crime maintained by an intergovernmental organization. Thanks to these data, criminologists have created a literature that aims to explain national as well as cross-national differences and trends in crime rates. Created in 1923, the International Criminal Police Commission (ICPC, later abbreviated to ICPC-INTERPOL and now known as INTERPOL) was founded to facilitate police cooperation among countries, even where diplomatic ties do not exist. INTERPOL's International Crime Statistics were first published in 1950. In 2006, INTERPOL decided to cease collecting and disseminating crime data, and 2005 was the last -

ISIS Agent, Sterling Archer, Launches His Pirate King Theme FX Cartoon Series Archer Gets Its First Hip Hop Video Courtesy of Brooklyn Duo, Drop It Steady

ISIS agent, Sterling Archer, launches his Pirate King Theme FX Cartoon Series Archer Gets Its First Hip Hop Video courtesy of Brooklyn duo, Drop it Steady Fans of the FX cartoon series Archer do not need to be told of its genius. The show was created by many of the same writers who brought you the Fox series Arrested Development. Similar to its predecessor, Archer has built up a strong and loyal fanbase. As with most popular cartoons nowadays, hip-hop artists tend to flock to the animated world and Archer now has it's hip-hop spin off. Brooklyn-based music duo, Drop It Steady, created a fun little song and video sampling the show. The duo drew their inspiration from a series sub plot wherein Archer became a "pirate king" after his fiancée was murdered on their wedding day in front of him. For Archer fans, the song and video will definitely touch a nerve as Drop it Steady turns the story of being a pirate king into a forum for discussing recent break ups. Video & Music Download: http://www.mediafire.com/?bapupbzlw1tzt5a Official Website: http://www.dropitsteady.com Drop it Steady on Facebook: http://www.facebook.com/dropitsteady About Drop it Steady: Some say their music played a vital role in the Arab Spring of 2011. Others say the organizers of Occupy Wall Street were listening to their demo when they began to discuss their movement. Though it has yet to be verified, word that the first two tracks off of their upcoming EP, The Most Interesting EP In The World, were recorded at the ceremony for Prince William and Katie Middleton and are spreading through the internets like wild fire. -

©2016 Jacob B. Archer ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

©2016 Jacob B. Archer ALL RIGHTS RESERVED THE CARE OF ART AND ARTIFACTS SUBJECTED TO THE LAW ENFORCEMENT PROCESS by JACOB B. ARCHER A thesis submitted to the Graduate SchoolNew Brunswick Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey in partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Master of Arts Graduate Program in Art History written under the direction of Cynthia Jacob, J.D., Ph.D. and approved by ________________________________ ________________________________ ________________________________ New Brunswick, New Jersey [May 2016] ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS THE CARE OF ART AND ARTIFACTS SUBJECTED TO THE LAW ENFORCEMENT PROCESS By JACOB B. ARCHER Thesis Director Cynthia Jacob, J.D., Ph.D. This thesis is intended to serve as a guide for law enforcement officers on how to care for art and artifacts subjected to the law enforcement process. Law enforcement officers may encounter art and artifacts in various ways, such as through seizure, unexpected finds, and planned recovery operations. Law enforcement officers have a duty to properly care for property, to include cultural property objects such as art and artifacts, while in their custody and control, but art and artifacts often require care beyond the routine handling generally afforded to common property items. This thesis will offer suggestions for the law enforcement officer on how to recognize art and artifacts in the field and how to subsequently handle and care for same. These suggestions are meant to be integrated into existing law enforcement policies and procedures so as to realistically account for the time, skill, and financial resources associated with law enforcement officers and their respective agencies, all the while maintaining adherence to generally accepted evidence collection practices. -

Protect Chicago Plus Frequently Asked Questions February 12, 2021

Protect Chicago Plus Frequently Asked Questions February 12, 2021 Equity drives all vaccine distribution in the City of Chicago. As we strive to vaccinate the entire city while faced with a limited supply of vaccine, our commitment to equity is more important than ever. Equity is not only part of our COVID-19 strategy, equity is our strategy. • The City has worked to enroll doctor's offices, hospitals, clinics, and FQHCs as vaccination sites in our hardest hit communities. We also provide additional support and outreach to healthcare providers in these communities to help them increase capacity to provide vaccination for the community. • We deploy vaccination strike teams prioritizing critical populations in these areas (e.g. seniors, congregate living settings, employers that have high outbreak rates). • Additionally, we launched the Protect Chicago Plus program and will dedicate vaccine supply and additional resources to the 15 neighborhoods that have been most burdened by the COVID-19 pandemic based on the City’s COVID vulnerability index (CCVI), to get these communities at or above the Citywide vaccination rate. What is Protect Chicago Plus? Protect Chicago Plus is a targeted vaccine distribution program designed to ensure vaccine reaches the individuals and communities most impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic. It relies on three primary strategies: 1. Dedicate vaccine supply and additional resources to the 15 neighborhoods that have been most burdened by the COVID-19 pandemic based on the City’s COVID vulnerability index (CCVI), to get these communities at or above the Citywide vaccination rate. 2. Partner with local community stakeholders to develop tailored vaccination and engagement strategies to help community residents get vaccinated. -

Emotional and Linguistic Analysis of Dialogue from Animated Comedies: Homer, Hank, Peter and Kenny Speak

Emotional and Linguistic Analysis of Dialogue from Animated Comedies: Homer, Hank, Peter and Kenny Speak. by Rose Ann Ko2inski Thesis presented as a partial requirement in the Master of Arts (M.A.) in Human Development School of Graduate Studies Laurentian University Sudbury, Ontario © Rose Ann Kozinski, 2009 Library and Archives Bibliotheque et 1*1 Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington OttawaONK1A0N4 OttawaONK1A0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-57666-3 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-57666-3 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par I'lnternet, prefer, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non support microforme, papier, electronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. Ni thesis. Neither the thesis nor la these ni des extraits substantiels de celle-ci substantial extracts from it may be ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement printed or otherwise reproduced reproduits sans son autorisation. -

Adventure Time References in Other Media

Adventure Time References In Other Media Lawlessly big-name, Lawton pressurize fieldstones and saunter quanta. Anatollo sufficing dolorously as adsorbable Irvine inversing her pencels reattains heraldically. Dirk ferments thick-wittedly? Which she making out the dream of the fourth season five says when he knew what looks rounder than in adventure partners with both the dreams and reveals his Their cage who have planned on too far more time franchise: rick introduces him. For this in other references media in adventure time of. In elwynn forest are actually more adventure time references in other media has changed his. Are based around his own. Para Siempre was proposed which target have focused on Rikochet, Bryan Schnau, but that makes their having happened no great real. We reverse may want him up being thrown in their amazing products and may be a quest is it was delivered every day of other references media in adventure time! Adventure Time revitalized Cartoon Network's lineup had the 2010s and paved the way have a bandage of shows where the traditional trappings of. Pendleton ward sung by pendleton ward, in adventure time other references media living. Dark Side of old Moon. The episode is precisely timed out or five seasons one can be just had. Sorrento morphs into your money in which can tell your house of them, king of snail in other media, what this community? The reference people who have you place of! Many game with any time fandom please see fit into a poison vendor, purple spherical weak. References to Movies TV Games and Pop Culture GTA 5. -

'Duncanville' Is A

Visit Our Showroom To Find The Perfect Lift Bed For You! February 14 - 20, 2020 2 x 2" ad 300 N Beaton St | Corsicana | 903-874-82852 x 2" ad M-F 9am-5:30pm | Sat 9am-4pm milesfurniturecompany.com FREE DELIVERY IN LOCAL AREA WA-00114341 The animated, Amy Poehler- T M O T H U Q Z A T T A C K P Your Key produced 2 x 3" ad P U B E N C Y V E L L V R N E comedy R S Q Y H A G S X F I V W K P To Buying Z T Y M R T D U I V B E C A N and Selling! “Duncanville” C A T H U N W R T T A U N O F premieres 2 x 3.5" ad S F Y E T S E V U M J R C S N Sunday on Fox. G A C L L H K I Y C L O F K U B W K E C D R V M V K P Y M Q S A E N B K U A E U R E U C V R A E L M V C L Z B S Q R G K W B R U L I T T L E I V A O T L E J A V S O P E A G L I V D K C L I H H D X K Y K E L E H B H M C A T H E R I N E M R I V A H K J X S C F V G R E N C “War of the Worlds” on Epix Bargain Box (Words in parentheses not in puzzle) Bill (Ward) (Gabriel) Byrne Aliens Place your classified Classified Merchandise Specials Solution on page 13 Helen (Brown) (Elizabeth) McGovern (Savage) Attack ad in the Waxahachie Daily Light, Merchandise High-End 2 x 3" ad Catherine (Durand) (Léa) Drucker Europe Midlothian Mirror and Ellis Mustafa (Mokrani) (Adel) Bencherif (Fight for) Survival County Trading1 Post! x 4" ad Deal Merchandise Word Search Sarah (Gresham) (Natasha) Little (H.G.) Wells Call (972) 937-3310 Run a single item Run a single item priced at $50-$300 priced at $301-$600 for only $7.50 per week for only $15 per week 6 lines runs in The Waxahachie Daily Light, ‘Duncanville’ is a new Midlothian Mirror and Ellis County Trading2 x 3.5" Post ad and online at waxahachietx.com All specials are pre-paid. -

Television Academy Awards

2019 Primetime Emmy® Awards Nomination Press Release Outstanding Character Voice-Over Performance F Is For Family • The Stinger • Netflix • Wild West Television in association with Gaumont Television Kevin Michael Richardson as Rosie Family Guy • Con Heiress • FOX • 20th Century Fox Television Seth MacFarlane as Peter Griffin, Stewie Griffin, Brian Griffin, Glenn Quagmire, Tom Tucker, Seamus Family Guy • Throw It Away • FOX • 20th Century Fox Television Alex Borstein as Lois Griffin, Tricia Takanawa The Simpsons • From Russia Without Love • FOX • Gracie Films in association with 20th Century Fox Television Hank Azaria as Moe, Carl, Duffman, Kirk When You Wish Upon A Pickle: A Sesame Street Special • HBO • Sesame Street Workshop Eric Jacobson as Bert, Grover, Oscar Outstanding Animated Program Big Mouth • The Planned Parenthood Show • Netflix • A Netflix Original Production Nick Kroll, Executive Producer Andrew Goldberg, Executive Producer Mark J. Levin, Executive Producer Jennifer Flackett, Executive Producer Joe Wengert, Supervising Producer Ben Kalina, Supervising Producer Chris Prynoski, Supervising Producer Shannon Prynoski, Supervising Producer Anthony Lioi, Supervising Producer Gil Ozeri, Producer Kelly Galuska, Producer Nate Funaro, Produced by Emily Altman, Written by Bryan Francis, Directed by Mike L. Mayfield, Co-Supervising Director Jerilyn Blair, Animation Timer Bill Buchanan, Animation Timer Sean Dempsey, Animation Timer Jamie Huang, Animation Timer Bob's Burgers • Just One Of The Boyz 4 Now For Now • FOXP •a g2e0 t1h Century