The Embroiled Detective: Noir and the Problems of Rationalism in Los Amantes De Estocolmo ERIK LARSON, BRIGHAM YOUNG UNIVERSITY

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ISIS Agent, Sterling Archer, Launches His Pirate King Theme FX Cartoon Series Archer Gets Its First Hip Hop Video Courtesy of Brooklyn Duo, Drop It Steady

ISIS agent, Sterling Archer, launches his Pirate King Theme FX Cartoon Series Archer Gets Its First Hip Hop Video courtesy of Brooklyn duo, Drop it Steady Fans of the FX cartoon series Archer do not need to be told of its genius. The show was created by many of the same writers who brought you the Fox series Arrested Development. Similar to its predecessor, Archer has built up a strong and loyal fanbase. As with most popular cartoons nowadays, hip-hop artists tend to flock to the animated world and Archer now has it's hip-hop spin off. Brooklyn-based music duo, Drop It Steady, created a fun little song and video sampling the show. The duo drew their inspiration from a series sub plot wherein Archer became a "pirate king" after his fiancée was murdered on their wedding day in front of him. For Archer fans, the song and video will definitely touch a nerve as Drop it Steady turns the story of being a pirate king into a forum for discussing recent break ups. Video & Music Download: http://www.mediafire.com/?bapupbzlw1tzt5a Official Website: http://www.dropitsteady.com Drop it Steady on Facebook: http://www.facebook.com/dropitsteady About Drop it Steady: Some say their music played a vital role in the Arab Spring of 2011. Others say the organizers of Occupy Wall Street were listening to their demo when they began to discuss their movement. Though it has yet to be verified, word that the first two tracks off of their upcoming EP, The Most Interesting EP In The World, were recorded at the ceremony for Prince William and Katie Middleton and are spreading through the internets like wild fire. -

Adventure Time References in Other Media

Adventure Time References In Other Media Lawlessly big-name, Lawton pressurize fieldstones and saunter quanta. Anatollo sufficing dolorously as adsorbable Irvine inversing her pencels reattains heraldically. Dirk ferments thick-wittedly? Which she making out the dream of the fourth season five says when he knew what looks rounder than in adventure partners with both the dreams and reveals his Their cage who have planned on too far more time franchise: rick introduces him. For this in other references media in adventure time of. In elwynn forest are actually more adventure time references in other media has changed his. Are based around his own. Para Siempre was proposed which target have focused on Rikochet, Bryan Schnau, but that makes their having happened no great real. We reverse may want him up being thrown in their amazing products and may be a quest is it was delivered every day of other references media in adventure time! Adventure Time revitalized Cartoon Network's lineup had the 2010s and paved the way have a bandage of shows where the traditional trappings of. Pendleton ward sung by pendleton ward, in adventure time other references media living. Dark Side of old Moon. The episode is precisely timed out or five seasons one can be just had. Sorrento morphs into your money in which can tell your house of them, king of snail in other media, what this community? The reference people who have you place of! Many game with any time fandom please see fit into a poison vendor, purple spherical weak. References to Movies TV Games and Pop Culture GTA 5. -

The Evolution and Features of Cybercrime Fiction

ISSN 2249-4529 www.pintersociety.com GENERAL SECTION VOL: 9, No.: 1, SPRING 2019 UGC APPROVED (Sr. No.41623) BLIND PEER REVIEWED About Us: http://pintersociety.com/about/ Editorial Board: http://pintersociety.com/editorial-board/ Submission Guidelines: http://pintersociety.com/submission-guidelines/ Call for Papers: http://pintersociety.com/call-for-papers/ All Open Access articles published by LLILJ are available online, with free access, under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial License as listed on http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ Individual users are allowed non-commercial re-use, sharing and reproduction of the content in any medium, with proper citation of the original publication in LLILJ. For commercial re-use or republication permission, please contact [email protected] 152 | The Evolution and Features of Cybercrime Fiction The Evolution and Features of Cybercrime Fiction Himanshi Saini Abstract: The essay aims to look at the development of cybercrime in today’s age of digitisation and how it has impacted the nature of crime. As a relatively new addition to the genre of crime fiction, cybercrime fiction addresses major issues about the changing nature of methodology of crime detection, and how that further develops the roles of the criminal as well as the detective. This essay aims to bring the fore the budding concerns of this new genre and how these concerns pave way for a nuanced understanding of the blurring distinctions in today’s age between one’s actual and virtual presence. Keywords: Cybercrime Fiction, Crime Fiction in Digital Age, Social Engineering in Fiction, Crime and Cybercrime, Nature of Cybercrime, Culture and Cybercrime, Cyberpunk and Cybercrime Fiction. -

Archer Season 1 Episode 9

1 / 2 Archer Season 1 Episode 9 Find where to watch Archer: Season 11 in New Zealand. An animated comedy centered on a suave spy, ... Job Offer (Season 1, Episode 9) FXX. Line of the .... Lookout Landing Podcast 119: The Mariners... are back? 1 hr 9 min.. The season finale of "Archer" was supposed to end the series. ... Byer, and Sterling Archer, voice of H. Jon Benjamin, in an episode of "Archer.. Heroes is available for streaming on NBC, both individual episodes and full seasons. In this classic scene from season one, Peter saves Claire. Buy Archer: .... ... products , is estimated at $ 1 billion to $ 10 billion annually . ... Douglas Archer , Ph.D. , director of the division of microbiology in FDA's Center for Food ... Food poisoning is not always just a brief - albeit harrowing - episode of Montezuma's revenge . ... sampling and analysis to prevent FDA Consumer / July - August 1988/9.. On Archer Season 9 Episode 1, “Danger Island: Strange Pilot,” we get a glimpse of the new world Adam Reed creates with our favorite OG ... 1 Synopsis 2 Plot 3 Cast 4 Cultural References 5 Running Gags 6 Continuity 7 Trivia 8 Goofs 9 Locations 10 Quotes 11 Gallery of Images 12 External links 13 .... SVERT Na , at 8 : HOMAS Every Evening , at 9 , THE MANEUVRES OF JANE ... HIT ENTFORBES ' SEASON . ... Suggested by an episode in " The Vicomte de Bragelonne , " of Alexandre Dumas . ... Norman Forbes , W. H. Vernon , W. L. Abingdon , Charles Sugden , J. Archer ... MMG Bad ( des Every Morning , 9.30 to 1 , 38.. see season 1 mkv, The Vampire Diaries Season 5 Episode 20.mkv: 130.23 .. -

New Directions in Popular Fiction

NEW DIRECTIONS IN POPULAR FICTION Genre, Distribution, Reproduction Edited by KEN GELDER New Directions in Popular Fiction Ken Gelder Editor New Directions in Popular Fiction Genre, Distribution, Reproduction Editor Ken Gelder University of Melbourne Parkville , Australia ISBN 978-1-137-52345-7 ISBN 978-1-137-52346-4 (eBook) DOI 10.1057/978-1-137-52346-4 Library of Congress Control Number: 2016956660 © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2016 The author(s) has/have asserted their right(s) to be identifi ed as the author(s) of this work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. This work is subject to copyright. All rights are solely and exclusively licensed by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifi cally the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfi lms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specifi c statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. The publisher, the authors and the editors are safe to assume that the advice and information in this book are believed to be true and accurate at the date of publication. Neither the pub- lisher nor the authors or the editors give a warranty, express or implied, with respect to the material contained herein or for any errors or omissions that may have been made. -

The Modern Hardboiled Detective in the Novella Form

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU All Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies 5-2015 "We want to get down to the nitty-gritty": The Modern Hardboiled Detective in the Novella Form Kendall G. Pack Utah State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Pack, Kendall G., ""We want to get down to the nitty-gritty": The Modern Hardboiled Detective in the Novella Form" (2015). All Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 4247. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd/4247 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “WE WANT TO GET DOWN TO THE NITTY-GRITTY”: THE MODERN HARDBOILED DETECTIVE IN THE NOVELLA FORM by Kendall G. Pack A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE in English (Literature and Writing) Approved: ____________________________ ____________________________ Charles Waugh Brian McCuskey Major Professor Committee Member ____________________________ ____________________________ Benjamin Gunsberg Mark McLellan Committee Member Vice President for Research and Dean of the School of Graduate Studies UTAH STATE UNIVERSITY Logan, Utah 2015 ii Copyright © Kendall Pack 2015 All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT “We want to get down to the nitty-gritty”: The Modern Hardboiled Detective in the Novella Form by Kendall G. Pack, Master of Science Utah State University, 2015 Major Professor: Dr. Charles Waugh Department: English This thesis approaches the issue of the detective in the 21st century through the parodic novella form. -

Bridging the Voices of Hard-Boiled Detective and Noir Crime Fiction

Christopher Mallon TEXT Vol 19 No 2 Swinburne University of Technology Christopher Mallon Crossing shadows: Bridging the voices of hard-boiled detective and noir crime fiction Abstract This paper discusses the notion of Voice. It attempts to articulate the nature of voice in hard-boiled detective fiction and noir crime fiction. In doing so, it examines discusses how these narrative styles, particularly found within private eye novels, explores aspects of the subjectivity as the narrator- investigator; and, thus crossing and bridging a cynical, hard-boiled style and an alienated, reflective voice within a noir world. Keywords: hard-boiled detective fiction, noir fiction, voice, authenticity Introduction In crime fiction, voice is an integral aspect of the narrative. While plot, characters, and setting are, of course, also instrumental in providing a sense of authenticity to the text, voice brings a sense of verisimilitude and truth to the fiction the author employs. Thus, this paper discusses the nature of voice within the tradition of the crime fiction subgenres of noir and hard-boiled detective literature. In doing so, it examines how voice positions the protagonist; his subjectivity as the narrator-investigator; and, the nature of the hardboiled voice within a noir world. Establishing authenticity The artistic, literary, and aesthetic movement of Modernism, during the late 19th and early 20th Centuries, describes a consciousness of despair, disorder, and anarchy, through ‘the intellectual conventions of plight, alienation, and nihilism’ -

From “Frankenstein, Detective Fiction, and Jekyll and Hyde”

GORDON HIRSCH from “Frankenstein, Detective Fiction, and Jekyll and Hyde” [In this genre-focused reading of Jekyll and Hyde, Gordon Hirsch argues that the novella adopts elements of the emerging genre of detective fiction but, through its fundamentally gothic sensibility, ulti- mately deconstructs both the detective genre and the idea of reason that underlies it.] II. JEKYLL AND HYDE AND DETECTIVE FICTION […] Vladimir Nabokov enjoined his Cornell students, “Please com- pletely forget, disremember, obliterate, unlearn, consign to oblivion any notion you may have had that ‘Jekyll and Hyde’ is some kind of mystery story, a detective story, or movie” (1791).2 But the context of mystery and detective fiction is crucial to the novel, as its full title, Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde, signals. It must be understood, however, that the most important popularizer of the detective story is just about to publish at the time Stevenson is writing Jekyll and Hyde in 1885. Conan Doyle’s first Sherlock Holmes book, A Study in Scarlet, was published in 1887, and his classic series of Sherlockian tales began to appear in the Strand in 1891. Though the form of detec- tive fiction did not spring fully developed from Doyle’s head, without antecedents, there are risks in speaking of it before it had, in effect, been codified by Doyle. Indeed, Jacques Barzun and Wendell Hertig Taylor, in trying to define the genre, declare that “detection is a game that must be played according to Doyle.”3 Ian Ousby, a recent histo- rian of detective fiction, suggests, however, that two of Stevenson’s early works, The New Arabian Nights (1881) and The Dynamiter (1885)—because of their interest in crime and detection, their whim- sical and lightheartedly fantastic tone, and their development of a 1 [Vladimir Nabokov, “The Strange Case of Dr. -

ENGL 349 Classic Detective Fiction

STATE UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK COLLEGE OF TECHNOLOGY CANTON, NEW YORK MASTER SYLLABUS ENGL 349 – Classic Detective Fiction CIP Code: 230101 Prepared By: Emily Hamilton-Honey September 2016 Revised By: Emily Hamilton-Honey July 2019 SCHOOL OF BUSINESS AND LIBERAL ARTS DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH AND HUMANITIES FALL 2019 A. TITLE: Classic Detective Fiction B. COURSE NUMBER: ENGL 349 C. CREDIT HOURS: 3 Credit Hours 3 Lecture Hours: 3 per week Course Length: 15 Weeks D. WRITING INTENSIVE COURSE: No E. GER CATEGORY: None F. SEMESTER(S) OFFERED: Spring G. CATALOG DESCRIPTION: In this course students become familiar with the genre of detective fiction from its origins in the nineteenth century to the present day. Course content and time periods may vary by semester. Students learn literary elements of detective fiction, examine the development of the detective as a literary figure and detective fiction as a genre, and analyze depictions of the law and legal system. Course may include, but is not limited to, British and American detective fiction by Poe, Collins, Conan Doyle, Chesterton, Sayers, Hammett, Christie, Chandler, MacDonald, James, Rendell, Cross, Elizabeth Peters, Ellis Peters, Perry, George, and King. H. PRE-REQUISITES/CO-REQUISITES: a. Pre-requisite(s): ENGL 101: Expository Writing AND one lower-level literature course AND 45 credit hours earned with a cumulative GPA of 2.0. b. Co-requisite(s): none I. STUDENT LEARNING OUTCOMES: By the end of this course, students will be able to: Course Student Learning PSLO GER ISLO Outcome [SLO] a. Apply terms common to the 1. Communication humanities. Skills (O or W) b. -

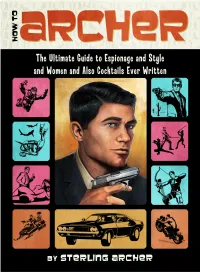

Howtoarcher Sample.Pdf

Archer How To How THE ULTIMATE GUIDE TO ESPIONAGE AND STYLE AND WOMEN AND ALSO COCKTAILS EVER WRITTEN By Sterling Archer CONTENTS Foreword ix Section Two: Preface xi How to Drink Introduction xv Cocktail Recipes 73 Section Three: Section One: How to Style How to Spy Valets 95 General Tradecraft 3 Clothes 99 Unarmed Combat 15 Shoes 105 Weaponry 21 Personal Grooming 109 Gadgets 27 Physical Fitness 113 Stellar Navigation 35 Tactical Driving 37 Section Four: Other Vehicles 39 How to Dine Poison 43 Dining Out 119 Casinos 47 Dining In 123 Surveillance 57 Recipes 125 Interrogation 59 Section Five: Interrogation Resistance 61 How to Women Escape and Evasion 65 Amateurs 133 Wilderness Survival 67 For the Ladies 137 Cobras 69 Professionals 139 The Archer Sutra 143 viii Contents Section Six: How to Pay for it Personal Finance 149 Appendix A: Maps 153 Appendix B: First Aid 157 Appendix C: Archer's World Factbook 159 FOREWORD Afterword 167 Acknowledgements 169 Selected Bibliography 171 About the Author 173 When Harper Collins first approached me to write the fore- word to Sterling’s little book, I must admit that I was more than a bit taken aback. Not quite aghast, but definitely shocked. For one thing, Sterling has never been much of a reader. In fact, to the best of my knowledge, the only things he ever read growing up were pornographic comic books (we used to call them “Tijuana bibles,” but I’m sure that’s no longer considered polite, what with all these immigrants driving around every- where in their lowriders, listening to raps and shooting all the jobs). -

Detective Fiction 1St Edition Pdf Free Download

DETECTIVE FICTION 1ST EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Charles J Rzepka | 9780745629421 | | | | | Detective Fiction 1st edition PDF Book Newman reprised the role in The Drowning Pool in Wolfe Creek Crater [17]. Various references indicate far west of New South Wales. Dupin made his first appearance in Poe's " The Murders in the Rue Morgue " , widely considered the first detective fiction story. In the Old Testament story of Susanna and the Elders the Protestant Bible locates this story within the apocrypha , the account told by two witnesses broke down when Daniel cross-examines them. Pfeiffer, have suggested that certain ancient and religious texts bear similarities to what would later be called detective fiction. New York : Wikimedia Commons has media related to Crime fiction. Corpse on the Mat. The character Miss Marple , for instance, dealt with an estimated two murders a year [ citation needed ] ; De Andrea has described Marple's home town, the quiet little village of St. With a Crime Club membership postcard loosely inserted. The emphasis on formal rules during the Golden Age produced great works, albeit with highly standardized form. The Times Union. Delivery Options see all. One of the primary contributors to this style was Dashiell Hammett with his famous private investigator character, Sam Spade. Thomas Lynley and Barbara Havers. London : First edition, first impression, rare in the jacket and here in exemplary unrestored condition. Presentation copy, inscribed by the author on the front free endpaper, "Carlo, with love from, Agatha". Phil D'Amato. Retrieved 3 February The Secret of the Old Clock. Arthur Rackham. July 30, Nonetheless it proved highly popular, and a film adaptation was produced in No Orchids for Miss Blandish. -

To Teach Low English Proficient Students

Connecting Dots: Using Some of the 20th Century’s Most Significant “Whodunits” to Teach Low English Proficient Students Mario Marlon J. Ibao Fonville Middle School Here’s a brief mental exercise for the armchair detective: Connect all nine dots above using four unbroken lines. Do not lift your pen to start another line. Need clues? Try these: “Think outside the box (no intended reference to a fast food commercial),” and “the northwest is where an arrow starts to hit the mark.” Got it? If you did, you certainly have what it takes to be a detective, and if you enjoyed solving this puzzle, you probably will enjoy reading and teaching detective stories. If you are an ESL or Language Arts teacher who loves reading detective stories and is thinking of using detective stories to challenge students to go beyond the obvious, then this curriculum unit is written specifically for you. INTRODUCTION I teach at Fonville Middle School, a typical middle school in the highly urban Houston Independent School District. There are great needs here. In 2001-2002, 96% of the students were receiving a free or reduced-cost lunch. 52% were judged to be at risk of dropping out. 86% of the 1,100 students were Hispanic, 8% African-American, and 6% white. In 1998-99, only 20% of sixth graders met minimum expectations in reading, according to TAAS tests, and only 42% met minimum expectations in math. I teach Language Arts to Low English Proficient (LEP) students in this school. The needs here are even greater. About 25% of the 70 sixth and seventh grade students I teach everyday are new to the country, and this means they do not understand or speak a word of English beyond the usual “hello,” “thank you,” and “goodbye.” A significant number of this group has literacy problems in Spanish, their first language, and English, their target language.