A Political History of the UN Convention Against Transnational Organized Crime

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Notes for Side Event on West Africa

EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT Special Committee on Organized Crime, Corruption and Money-laundering (CRIM) Anti-money laundering A key element to fight narco-crime Antonio Maria Costa United Nations Under-Secretary General (2002-10) Editor, Journal of Policy Modelling (Elsevier) [email protected] www.AntonioMariaCosta.com Abstract: this statement examines the economic, financial and strategic dimensions of organized crime (especially drug trafficking) and shows that governments’ inability to deal with it is due to poor understanding of: (i.) the extent crime conditions society at large, (ii.) the way it has infiltrated legitimate business (especially banking), and (iii.) the power it has accumulated thanks to the behaviour of unscrupulous white-collar professionals (bankers, lawyers, notaries, realtors, accountants etc), all too willing to hide and recycle mafia resources. Current crime-control responses, based on police activity meant to identify, seize and punish suspects, are proving only partially effective: criminals locked up in prison or liquidated are rapidly replaced by new recruits, whose supply is infinitely elastic, especially in developing countries. The fight against transnational organized crime should rather focus on disrupting markets and illicit trade flows. Next the statement provides evidence that organized crime is an economic force motivated by economic stimuli, driven by mini(risk)/max(revenue) principles. Therefore crime must be fought on economic grounds, especially deleveraging its enormous assets (by means of much stronger anti-money laundering measures than presently in place). Above all governments should, individually and collectively, follow the money trail to identify and punish financial institutions responsible of blood-money laundering. The statement concludes with a pessimistic note. -

The Differences of Slovenian and Italian Daily Practices Experienced in the First Wave of Covid-19 Pandemic

The Differences of Slovenian and Italian Daily Practices Experienced in the First Wave of Covid-19 Pandemic Saša Pišot ( [email protected] ) Science and Research Centre Koper Boštjan Šimunič Science and Research Centre Koper Ambra Gentile Università degli Studi di Palermo Antonino Bianco Università degli Studi di Palermo Gianluca Lo Coco Università degli Studi di Palermo Rado Pišot Science and Research Centre Koper Patrik Dird Faculty of Sport and Physical Education, University of Novi Sad, Serbia Ivana Milovanović Faculty of Sport and Physical Education, University of Novi Sad, Serbia Research Article Keywords: Physical activity and inactivity behavior, dietary/eating habits, well-being, home connement, COVID-19 pandemic measures Posted Date: June 9th, 2021 DOI: https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-537321/v1 License: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Read Full License Page 1/18 Abstract Background: The COVID-19 pandemic situation with the lockdown of public life caused serious changes in people's everyday practices. The study evaluates the differences between Slovenia and Italy in health- related everyday practices induced by the restrictive measures during rst wave of the COVID-19 pandemic. Methods: The study examined changes through an online survey conducted in nine European countries from April 15-28, 2020. The survey included questions from a simple activity inventory questionnaire (SIMPAQ), the European Health Interview Survey, and some other questions. To compare changes between countries with low and high incidence of COVID-19 epidemic, we examine 956 valid responses from Italy (N=511; 50% males) and Slovenia (N=445; 26% males). -

Prison Abolition and Grounded Justice

Georgetown University Law Center Scholarship @ GEORGETOWN LAW 2015 Prison Abolition and Grounded Justice Allegra M. McLeod Georgetown University Law Center, [email protected] This paper can be downloaded free of charge from: https://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/facpub/1490 http://ssrn.com/abstract=2625217 62 UCLA L. Rev. 1156-1239 (2015) This open-access article is brought to you by the Georgetown Law Library. Posted with permission of the author. Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/facpub Part of the Criminal Law Commons, Criminal Procedure Commons, Criminology Commons, and the Social Control, Law, Crime, and Deviance Commons Prison Abolition and Grounded Justice Allegra M. McLeod EVIEW R ABSTRACT This Article introduces to legal scholarship the first sustained discussion of prison LA LAW LA LAW C abolition and what I will call a “prison abolitionist ethic.” Prisons and punitive policing U produce tremendous brutality, violence, racial stratification, ideological rigidity, despair, and waste. Meanwhile, incarceration and prison-backed policing neither redress nor repair the very sorts of harms they are supposed to address—interpersonal violence, addiction, mental illness, and sexual abuse, among others. Yet despite persistent and increasing recognition of the deep problems that attend U.S. incarceration and prison- backed policing, criminal law scholarship has largely failed to consider how the goals of criminal law—principally deterrence, incapacitation, rehabilitation, and retributive justice—might be pursued by means entirely apart from criminal law enforcement. Abandoning prison-backed punishment and punitive policing remains generally unfathomable. This Article argues that the general reluctance to engage seriously an abolitionist framework represents a failure of moral, legal, and political imagination. -

Introductory Handbook on the Prevention of Recidivism and the Social Reintegration of Offenders

Introductory Handbook on The Prevention of Recidivism and the Social Reintegration of Offenders CRIMINAL JUSTICE HANDBOOK SERIES Cover photo: © Rafael Olivares, Dirección General de Centros Penales de El Salvador. UNITED NATIONS OFFICE ON DRUGS AND CRIME Vienna Introductory Handbook on the Prevention of Recidivism and the Social Reintegration of Offenders CRIMINAL JUSTICE HANDBOOK SERIES UNITED NATIONS Vienna, 2018 © United Nations, December 2018. All rights reserved. The designations employed and the presentation of material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Publishing production: English, Publishing and Library Section, United Nations Office at Vienna. Preface The first version of the Introductory Handbook on the Prevention of Recidivism and the Social Reintegration of Offenders, published in 2012, was prepared for the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) by Vivienne Chin, Associate of the International Centre for Criminal Law Reform and Criminal Justice Policy, Canada, and Yvon Dandurand, crimi- nologist at the University of the Fraser Valley, Canada. The initial draft of the first version of the Handbook was reviewed and discussed during an expert group meeting held in Vienna on 16 and 17 November 2011.Valuable suggestions and contributions were made by the following experts at that meeting: Charles Robert Allen, Ibrahim Hasan Almarooqi, Sultan Mohamed Alniyadi, Tomris Atabay, Karin Bruckmüller, Elias Carranza, Elinor Wanyama Chemonges, Kimmett Edgar, Aida Escobar, Angela Evans, José Filho, Isabel Hight, Andrea King-Wessels, Rita Susana Maxera, Marina Menezes, Hugo Morales, Omar Nashabe, Michael Platzer, Roberto Santana, Guy Schmit, Victoria Sergeyeva, Zhang Xiaohua and Zhao Linna. -

GENERAL ASSEMBLY INFORMAL MEETING on PIRACY 14 May

GENERAL ASSEMBLY INFORMAL MEETING ON PIRACY 14 May 2010, United Nations Headquarters The problem of international maritime piracy has in the last few years gained global attention, particularly with the increasing incidents of piracy in the Gulf of Aden and especially off the coast of Somalia. Recent statistics from the International Maritime Bureau indicate that in 2009 alone pirates attacked 217 ships with 47 successful hijackings. Pirates extorted more than US $60 million in ransom, the largest payment on record. In 2008, there were 242 attacks with 111 successful hijackings and about US $40 million in ransom. The adverse security, political, legal, economic and social implications of this scourge are of serious concern to the international community. With regard to Somalia, the United Nations has taken actions aimed at strengthening and assisting the Transitional Federal Government (TFG) to improve the security situation in Somalia, which is essential for an enabling environment to fight piracy off the coast of Somalia. The Security Council has authorized measures to counter piracy and armed robbery off the coast of Somalia. A Contact Group on Piracy off the coast of Somalia CGPCS) has also been established. These efforts notwithstanding, the sovereignty, economy and security of Somalia remain under serious threat as a result of piracy. Piracy has a destabilizing effect on regional and global trade and security. There is therefore the necessity for global strategies to address the factors that trigger and sustain piracy. Moreover, its rapid geographical spread and complexity necessitate a deeper and more comprehensive look at the various facets of the problem in order to devise a collective and more coordinated response. -

5 Year Slurry Outlook As of 2021.Xlsx

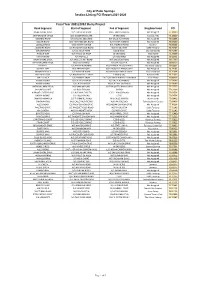

City of Palm Springs Section Listing PCI Report 2021-2026 Fiscal Year 2021/2022 Slurry Project Road Segment Start of Segment End of Segment Neighborhood PCI DINAH SHORE DRIVE W/S CROSSLEY ROAD WEST END OF BRIDGE Not Assigned 75.10000 SNAPDRAGON CIRCLE W/S GOLDENROD LANE W END (CDS) Andreas Hills 75.10000 ANDREAS ROAD E/S CALLE EL SEGUNDO E/S CALLE ALVARADO Not Assigned 75.52638 DILLON ROAD 321'' W/O MELISSA ROAD W/S KAREN AVENUE Not Assigned 75.63230 LOUELLA ROAD S/S LIVMOR AVENUE N/S ANDREAS ROAD Sunmor 75.66065 LEONARD ROAD S/S RACQUET CLUB ROAD N/S VIA OLIVERA Little Tuscany 75.70727 SONORA ROAD E/S EL CIELO ROAD E END (CDS) Los Compadres 75.71757 AMELIA WAY W/S PASEO DE ANZA W END (CDS) Vista Norte 75.78306 TIPTON ROAD N/S HWY 111 S/S RAILROAD Not Assigned 76.32931 DINAH SHORE DRIVE E/S SAN LUIS REY ROAD W/S CROSSLEY ROAD Not Assigned 76.57559 AVENIDA CABALLEROS N/S VISTA CHINO N/S VIA ESCUELA Not Assigned 76.60579 VIA EYTEL E/S AVENIDA PALMAS W/S AVENDA PALOS VERDES The Movie Colony 76.68892 SUNRISE WAY N/S ARENAS ROAD S/S TAHQUITZ CANYON WAY Not Assigned 76.74161 HERMOSA PLACE E/S MISSION ROAD W/S N PALM CANYON DRIVE Old Las Palmas 76.75654 HILLVIEW COVE E/S ANDREAS HILLS DRIVE E END (CSD) Andreas Hills 76.77835 VIA ESCUELA E/S FARRELL DRIVE 130'' E/O WHITEWATER CLUB DRIVE Gene Autry 76.80916 AMADO ROAD E/S CALLE SEGUNDO E/S CALLE ALVARADO Not Assigned 77.54599 AMADO ROAD E/S CALLE ENCILIA W/S CALLE EL SEGUNDO Not Assigned 77.54599 AVENIDA CABALLEROS N/S RAMON ROAD S/S TAHQUITZ CANYON WAY Not Assigned 77.57757 DOLORES COURT LOS -

Introduction to Criminology

PART 1 © Nevarpp/iStockphoto/Getty Images Introduction to Criminology CHAPTER 1 Crime and Criminology. 3 CHAPTER 2 The Incidence of Crime . 35 1 © Tithi Luadthong/Shutterstock CHAPTER 1 Crime and Criminology Crime and the fear of crime have permeated the fabric of American life. —Warren E. Burger, Chief Justice, U.S. Supreme Court1 Collective fear stimulates herd instinct, and tends to produce ferocity toward those who are not regarded as members of the herd. —Bertrand Russell2 OBJECTIVES • Define criminology, and understand how this field of study relates to other social science disciplines. Pg. 4 • Understand the meaning of scientific theory and its relationship to research and policy. Pg. 8 • Recognize how the media shape public perceptions of crime. Pg. 19 • Know the criteria for establishing causation, and identify the attributes of good research. Pg. 13 • Understand the politics of criminology and the importance of social context. Pg. 18 • Define criminal law, and understand the conflict and consensus perspectives on the law. Pg. 5 • Describe the various schools of criminological theory and the explanations that they provide. Pg. 9 of the public’s concern about the safety of their com- Introduction munities, crime is a perennial political issue that can- Crime is a social phenomenon that commands the didates for political office are compelled to address. attention and energy of the American public. When Dealing with crime commands a substantial por- crime statistics are announced or a particular crime tion of the country’s tax dollars. Criminal justice sys- goes viral, the public demands that “something be tem operations (police, courts, prisons) cost American done.” American citizens are concerned about their taxpayers over $270 billion annually. -

The Vienna Spirit

The Vienna Spirit Report on the 40th Meeting of the Chairmen and Coordinators of the Group of 77 and China The Vienna Spirit Report on the 40th Meeting of the Chairmen and Coordinators of the Group of 77 and China Vienna, 2007 The Vienna Chapter of the Group of 77 and China wishes to express its gratitude to the Director-General of the United Nations Industrial Development Organization, Mr. Kandeh Yumkella, and his staff, for co-hosting this important event, as well as for their invaluable support. We are also grateful to Mr. Mohamed ElBaradei, Director General of the International Atomic Energy Agency; Mr. Antonio Maria Costa, Director-General of the United Nations Office at Vienna and Executive Director of the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime; Mr. Mohammed Barkindo, Acting for the Secretary-General of the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries; and Mr. Suleiman J. Al-Herbish, Director-General of the OPEC Fund for International Development, for their generous hospitality, and for their interest in and support to the ideals of the Group. This publication has been prepared under the overall direction of His Excellency Ambassador Horacio Bazoberry, Permanent Representative of Bolivia and Chairman of the G-77 Vienna Chapter during 2006 and Mr. Aegerico Lacanlale, Director, Strategic Planning and Coordination Group. Mr. Paul Hesp, UNIDO consultant has prepared this report and was assisted by Ms. Annemarie Heuls, Office of the Chairman of the G-77 Vienna Chapter. Foreword Ambassador Dumisani S. Kumalo, Chairman of the G-77 during 2006. The meetings of the Chapters of the Group of 77 and China represent a response to the need for coordination among the different United Nations locations where the Group is operating. -

Prisoners of Solitude: Bringing History to Bear on Prison Health Policy Margaret Charleroy and Hilary Marland

Prisoners of Solitude: Bringing History to Bear on Prison Health Policy Margaret Charleroy and Hilary Marland Season two of the popular prison drama Orange is the New Black opens in a small concrete cell, no larger than a parking space. The cell is windowless and sparsely furnished; it holds a toilet, a sink and a limp bed. The only distinguishing feature we see is a mural of smeared egg, made by the cell's resident, the show's protagonist Piper Chapman. When a correctional officer arrives at this solitary confinement cell, he wakes her, and mocks her egg fresco. “This is art,” she insists. “This is a yellow warbler drinking out of a daffodil.” Her rambling suggests the confusion and disorientation associated with inmates in solitary confinement, who often become dazed after only a few days in isolation. As the scene continues, we see Piper exhibit further symptoms associated with both short- and long-term solitary confinement—memory loss, inability to reason, mood swings, anxiety—all indicating mental deterioration and impaired mental health. In this and other episodes, we begin to see solitary confinement as the greatest villain in the show, more villainous than any character a writer could create. The new and growing trend of television prison dramas like Orange is the New Black brings the issue of solitary confinement, along with other issues related to incarceration, to a more general audience, exposing very real problems in the failing contemporary prison system, not just in America, but worldwide. The show's success leads us to ask how history, alongside fictional dramas and contemporary case reports, can draw attention to the issue of solitary confinement. -

The Crust (239) 244-8488

8004 TRAIL BLVD THECRUSTPIZZA.NET NAPLES, FL 34108 THE CRUST (239) 244-8488 At The Crust we are committed to providing our guests with delicious food in a clean and friendly environment. Our food is MADE FROM SCRATCH for every order from ingredients that we prepare FRESH in our kitchen EACH DAY. PIZZA Prepared Using Our SIGNATURE HOUSE-MADE Dough – Thin, Crispy, and LIGHTLY SAUCED BUILD YOUR OWN 10 INCH 13 INCH 16 INCH * 12 INCH GLUTEN FREE Cheese .................................. 12.95 Cheese .................................. 16.95 Cheese ................................. 21.75 Cheese .................................. 17.95 Add Topping ......................... 1.10 Add Topping ......................... 2.20 Add Topping ......................... 2.80 Add Topping ......................... 2.20 TOPPINGS SAUCE CHEESE MEAT VEGGIES Marinara Provolone Pepperoni Mushrooms Black Olives Artichokes BBQ Feta Sausage Red Onions Green Olives Garlic Olive Oil Smoked Gouda Meatballs Tomatoes Kalamata Olives Spinach Pesto Gorgonzola Ham Green Peppers Pineapple Cilantro Bacon Banana Peppers Pickled Jalapeños Basil Grilled Chicken Caramelized Onions Anchovies SPECIALTIES 10 INCH ......13 INCH ......16 INCH .........*GF PALERMO .................................................................................................................................................................... 14.95 .......... 19.95 ........ 27.25 ........ 22.95 Olive Oil, Fresh Garlic, Provolone, Parmesan, Gorgonzola, Caramelized Onions BBQ .............................................................................................................................................................................. -

Palermo Open City: from the Mediterranean Migrant Crisis to a Europe Without Borders?

EUROPE AT A CROSSROADS : MANAGED INHOSPITALITY Palermo Open City: From the Mediterranean Migrant Crisis to a Europe Without Borders? LEOLUCA ORLANDO + SIMON PARKER LEOLUCA ORLANDO is the Mayor of Palermo and interview + essay the President of the Association of the Municipali- ties of Sicily. He was elected mayor for the fourth time in 2012 with 73% of the vote. His extensive and remarkable political career dates back to the late 1970s, and includes membership and a break PALERMO OPEN CITY, PART 1 from the Christian Democratic Party; the establish- ment of the Movement for Democracy La Rete (“The Network”); and election to the Sicilian Regional Parliament, the Italian National Parliament, as well as the European Parliament. Struggling against organized crime, reintroducing moral issues into Italian politics, and the creation of a democratic society have been at the center of Oralando’s many initiatives. He is currently campaigning for approaching migration as a matter of human rights within the European Union. Leoluca Orlando is also a Professor of Regional Public Law at the University of Palermo. He has received many awards and rec- ognitions, and authored numerous books that are published in many languages and include: Fede e Politica (Genova: Marietti, 1992), Fighting the Mafia and Renewing Sicilian Culture (San Fran- Interview with Leolucca Orlando, Mayor of Palermo, Month XX, 2015 cisco: Encounter Books, 2001), Hacia una cultura de la legalidad–La experiencia siciliana (Mexico City: Universidad Autonoma Metropolitana, 2005), PALERMO OPEN CITY, PART 2 and Ich sollte der nächste sein (Freiburg: Herder Leoluca Orlando is one of the longest lasting and most successful political lead- Verlag, 2010). -

States Simply Do Not Care the Failure of International Securitisation Of

International Journal of Drug Policy 68 (2019) 3–8 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect International Journal of Drug Policy journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/drugpo Policy analysis States simply do not care: The failure of international securitisation of drug control in Afghanistan T ⁎ Jorrit Kamminga Netherlands Institute of International Relations Clingendael, Clingendael 7, 2597 VH The Hague, the Netherlands ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: The link between the world drug problem and securitisation has been predominantly established to argue that an Illicit drugs existential threat discourse reinforces the international prohibitionist regime and makes it harder for alternative Afghanistan policy models to arise. This analysis is problematic for three main reasons. Firstly, it overestimates the current Securitisation strength of the international drug control regime as a normative and regulatory system that prescribes state Security behaviour. Secondly, the current international regime does not inhibit policy reforms. While the international Drug prohibition treaty system proves resistant to change, it is at the national and local levels where new drug policies arise. International regime ‘War on Drugs’ Moreover, these are generally not the draconian or emergency measures that successful securitisation would predict. Thirdly, the analysis so far misinterprets criminalisation or militarisation as evidence of securitisation. As the case of Afghanistan shows, securitisation attempts, such as those linking the Taliban and the illicit opium economy, may have reinforced the militarisation of drug control in Afghanistan, but did not elevate the illicit drug economy as an external threat or a top priority. While there have been short-lived spikes of attention and provincial level campaigns to eradicate poppy cultivation, these have never translated into a sustained structural effort to combat illicit drugs in Afghanistan.