Vipera Ursinii Rakosiensis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Case of Unusual Head Scalation in Vipera Ammodytes

North-Western Journal of Zoology 2019, vol.15 (2) - Correspondence: Notes 195 Castillo, G.N., González-Rivas C.J., Acosta J.C. (2018b): Salvator rufescens Article No.: e197504 (Argentine Red Tegu). Diet. Herpetological Review 49: 539-540. Received: 15. April 2019 / Accepted: 21. April 2019 Castillo, G.N., Acosta, J.C., Blanco, G.M. (2019): Trophic analysis and Available online: 25. April 2019 / Printed: December 2019 parasitological aspects of Liolaemus parvus (Iguania: Liolaemidae) in the Central Andes of Argentina. Turkish Journal of Zoology 43: 277-286. Castillo, G.N., Acosta J.C., Ramallo G., Pizarro J. (2018a): Pattern of infection by Gabriel Natalio CASTILLO1,2,3,*, Parapharyngodon riojensis Ramallo, Bursey, Goldberg 2002 (Nematoda: 1,4 Pharyngodonidae) in the lizard Phymaturus extrilidus from Puna region, Cynthia GONZÁLEZ-RIVAS Argentina. Annals of Parasitology 64: 83-88. and Juan Carlos ACOSTA1,2 Cruz, F.B., Silva, S., Scrocchi, G.J. (1998): Ecology of the lizard Tropidurus etheridgei (Squamata: Tropiduridae) from the dry Chaco of Salta, 1. Faculty of Exact, Physical and Natural Sciences, National University Argentina. Herpetological Natural History 6: 23-31. of San Juan, Av. Ignacio de la Roza 590, 5402, San Juan, Argentina. Goldberg, S.R., Bursey, C.R., Morando, M. (2004): Metazoan endoparasites of 12 2. DIBIOVA Research Office (Diversity and Biology of Vertebrates of species of lizards from Argentina. Comparative Parasitology 71: 208-214. the Arid), National University of San Juan, Av. Ignacio de la Lamas, M.F., Céspedez, J.A., Ruiz-García, J.A. (2016): Primer registro de Roza 590, 5402, San Juan, Argentina. nematodes parásitos para la culebra Xenodon merremi (Squamata, 3. -

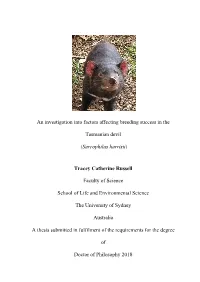

An Investigation Into Factors Affecting Breeding Success in The

An investigation into factors affecting breeding success in the Tasmanian devil (Sarcophilus harrisii) Tracey Catherine Russell Faculty of Science School of Life and Environmental Science The University of Sydney Australia A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2018 Faculty of Science The University of Sydney Table of Contents Table of Figures ............................................................................................................ viii Table of Tables ................................................................................................................. x Acknowledgements .........................................................................................................xi Chapter Acknowledgements .......................................................................................... xii Abbreviations ................................................................................................................. xv An investigation into factors affecting breeding success in the Tasmanian devil (Sarcophilus harrisii) .................................................................................................. xvii Abstract ....................................................................................................................... xvii 1 Chapter One: Introduction and literature review .............................................. 1 1.1 Devil Life History ................................................................................................... -

The Rufford Foundation Final Report

The Rufford Foundation Final Report Congratulations on the completion of your project that was supported by The Rufford Foundation. We ask all grant recipients to complete a Final Report Form that helps us to gauge the success of our grant giving. We understand that projects often do not follow the predicted course but knowledge of your experiences is valuable to us and others who may be undertaking similar work. Please be as honest as you can in answering the questions – remember that negative experiences are just as valuable as positive ones if they help others to learn from them. Please complete the form in English and be as clear and concise as you can. We will ask for further information if required. If you have any other materials produced by the project, particularly a few relevant photographs, please send these to us separately. Please submit your final report to [email protected]. Thank you for your help. Josh Cole, Grants Director Grant Recipient Details Your name Aleksandar Simović Distribution and conservation of the highly endangered Project title lowland populations of the Bosnian Adder (Vipera berus bosniensis) in Serbia RSG reference 17042-1 Reporting period March 2015 – March 2016 Amount of grant £ 5,000 Your email address [email protected] Date of this report 30.03.2016 1. Please indicate the level of achievement of the project’s original objectives and include any relevant comments on factors affecting this. achieved Not achieved Partially achieved Fully Objective Comments Precisely determine With very limited potential habitats in distribution Vojvodina province we found adders in 10 new UTM squares (10 x 10 km). -

The Adder (Vipera Berus) in Southern Altay Mountains

The adder (Vipera berus) in Southern Altay Mountains: population characteristics, distribution, morphology and phylogenetic position Shaopeng Cui1,2, Xiao Luo1,2, Daiqiang Chen1,2, Jizhou Sun3, Hongjun Chu4,5, Chunwang Li1,2 and Zhigang Jiang1,2 1 Key Laboratory of Animal Ecology and Conservation Biology, Institute of Zoology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, China 2 University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, China 3 Kanas National Nature Reserve, Buerjin, Urumqi, China 4 College of Resources and Environment Sciences, Xinjiang University, Urumqi, China 5 Altay Management Station, Mt. Kalamaili Ungulate Nature Reserve, Altay, China ABSTRACT As the most widely distributed snake in Eurasia, the adder (Vipera berus) has been extensively investigated in Europe but poorly understood in Asia. The Southern Altay Mountains represent the adder's southern distribution limit in Central Asia, whereas its population status has never been assessed. We conducted, for the first time, field surveys for the adder at two areas of Southern Altay Mountains using a combination of line transects and random searches. We also described the morphological characteristics of the collected specimens and conducted analyses of external morphology and molecular phylogeny. The results showed that the adder distributed in both survey sites and we recorded a total of 34 sightings. In Kanas river valley, the estimated encounter rate over a total of 137 km transects was 0.15 ± 0.05 sightings/km. The occurrence of melanism was only 17%. The small size was typical for the adders in Southern Altay Mountains in contrast to other geographic populations of the nominate subspecies. A phylogenetic tree obtained by Bayesian Inference based on DNA sequences of the mitochondrial Submitted 21 April 2016 cytochrome b (1,023 bp) grouped them within the Northern clade of the species but Accepted 18 July 2016 failed to separate them from the subspecies V. -

Cam15 Curic.Vp

Coll. Antropol. 33 (2009) Suppl. 2: 93–98 Original scientific paper Snakebites in Mostar Region, Bosnia and Herzegovina Ivo Curi}1, Snje`ana Curi}2, Ivica Bradari}1, Pero Bubalo1, Helien Bebek-Ivankovi}1, Jadranka Nikoli}1, Ozren Pola{ek3 and Nikola Bradari}4 1 Department for Infectious Diseases, University Clinical Hospital Mostar, Mostar, Bosnia and Herzegovina 2 Health Center Mostar, Mostar, Bosnia and Herzegovina 3 School of Public Health »Andrija [tampar«, School of Medicine, University of Zagreb, Zagreb, Croatia 4 University Hospital Center Split, Split, Croatia ABSTRACT The aim of this study was to provide an overview of the snakebites in patients hospitalized at the Mostar Clinical Hos- pital, admitted between 1983 and 2006. A total of 341 patients were recorded, with moderate men predominance (52.8%). Majority of patients were bitten for the first time (99.1%). In 98.8% of patients snakebite occurred to the bare skin, most commonly during June to September period (64.2%). Snakebites were the commonest in agricultural workers (48.1%). Until 2003 all admitted patients were treated according to Russel’s scheme (3-anti). As of 2003 new treatment scheme was applied, resulting in the reduction of antidote and supportive treatment use, causing a reduction in the number of clinically apparent allergic reactions. Serum sickness was recorded in only 2 patients, while lethal outcome was recorded in one (0.3%). Overall results indicate that lethality of snakebite is low, and that patients were often administered treat- ment without medical indication. High number of tourists as well as the presence of the peace keeping troops and other visiting personnel in this region make the snakebites and awareness on snakes not only a local issue, but also more gen- eral concern. -

Indigenous Reptiles

Reptiles Sylvain Ursenbacher info fauna & NLU, Universität Basel pdf can be found: www.ursenbacher.com/teaching/Reptilien_UNIBE_2020.pdf Reptilia: Crocodiles Reptilia: Tuataras Reptilia: turtles Rep2lia: Squamata: snakes Rep2lia: Squamata: amphisbaenians Rep2lia: Squamata: lizards Phylogeny Tetrapoda Synapsida Amniota Lepidosauria Squamata Sauropsida Anapsida Archosauria H4 Phylogeny H5 Chiari et al. BMC Biology 2012, 10:65 Amphibians – reptiles - differences Amphibians Reptiles numerous glands, generally wet, without or with limited number skin without scales of glands, dry, with scales most of them in water, no links with water, reproduction larval stage without a larval stage most of them in water, packed in not in water, hard shell eggs tranparent jelly (leathery or with calk) passive transmission of venom, some species with active venom venom toxic skin as passive protection injection Generally in humide and shady Generally dry and warm habitats areas, nearby or directly in habitats, away from aquatic aquatic habitats habitats no or limited seasonal large seasonal movements migration movements, limited traffic inducing big traffic problems problems H6 First reptiles • first reptiles: about 320-310 millions years ago • embryo is protected against dehydration • ≈ 305 millions years ago: a dryer period ➜ new habitats for reptiles • Mesozoic (252-66 mya): “Age of Reptiles” • large disparition of species: ≈ 252 and 65 millions years ago H7 Mesozoic Quick systematic overview total species CH species (oct 2017) Order Crocodylia (crocodiles) -

For the Hungarian Meadow Viper (Vipera Ursinii Rakosiensis)

Population and Habitat Viability Assessment (PHVA) For the Hungarian Meadow Viper (Vipera ursinii rakosiensis) 5 – 8 November, 2001 The Budapest Zoo Budapest, Hungary Workshop Report A Collaborative Workshop: The Budapest Zoo Conservation Breeding Specialist Group (SSC / IUCN) Sponsored by: The Budapest Zoo Tiergarten Schönbrunn, Vienna A contribution of the IUCN/SSC Conservation Breeding Specialist Group, in collaboration with The Budapest Zoo. This workshop was made possible through the generous financial support of The Budapest Zoo and Tiergarten Schönbrunn, Vienna. Copyright © 2002 by CBSG. Cover photograph courtesy of Zoltan Korsós, Hungarian Natural History Museum, Budapest. Title Page woodcut from Josephus Laurenti: Specimen medicum exhibens synopsin reptilium, 1768. Kovács, T., Korsós, Z., Rehák, I., Corbett, K., and P.S. Miller (eds.). 2002. Population and Habitat Viability Assessment for the Hungarian Meadow Viper (Vipera ursinii rakosiensis). Workshop Report. Apple Valley, MN: IUCN/SSC Conservation Breeding Specialist Group. Additional copies of this publication can be ordered through the IUCN/SSC Conservation Breeding Specialist Group, 12101 Johnny Cake Ridge Road, Apple Valley, MN 55124 USA. Send checks for US$35 (for printing and shipping costs) payable to CBSG; checks must be drawn on a US bank. Visa or MasterCard are also accepted. Population and Habitat Viability Assessment (PHVA) For the Hungarian Meadow Viper (Vipera ursinii rakosiensis) 5 – 8 November, 2001 The Budapest Zoo Budapest, Hungary CONTENTS Section I: Executive Summary 3 Section II: Life History and Population Viability Modeling 13 Section III: Habitat Management 37 Section IV: Captive Population Management 45 Section V: List of Workshop Participants 53 Section VI: Appendices Appendix A: Participant Responses to Day 1 Introductory Questions 57 Appendix I: Workshop Presentation Summaries Z. -

Predation on the Endangered Hungarian Meadow Viper (Vipera Ursinii Rakosiensis) by Badger (Meles Meles) and Fox (Vulpes Vulpes)

Predation on the endangered Hungarian meadow viper (Vipera ursinii rakosiensis) by Badger (Meles meles) and Fox (Vulpes vulpes) Attila Móré1, Edvárd Mizsei2 1Institute for Wildlife Conservation, Szent István University; [email protected] 2Centre for Ecological Research, Hungarian Academy of Sciences; [email protected] Abstract Hungarian meadow viper (Vipera ursinii rakosiensis) is a globally endangered reptile with a few sub-populations remained after habitat loss and fragmentation. Now all habitats is protected by law in Hungary and significant conservation effort have been implemented by habitat reconstruction, development and ex situ breeding and reintroductions, but the abundance is still very low and the impact of conservation interventions are nearly immeasurable according to densities. Hypotheses have been raised, as the predation pressure is the main factor influencing viper abundance. Here we analysed the diet of potential mammalian predators (Badger and Fox) at a Hungarian meadow viper habitat, and found high prevalence of viper remains in the processed faecal samples, and estimated a high number of preyed vipers within half season in a single site. Effective predator control is recommended to support habitat developments and reintroduction. Keywords: game; predator; predation control; predation pressure; conservation; snakes; reptiles. Introduction Meadow vipers (Vipera ursinii complex) are grassland specialist reptiles preying on grasshoppers (Baron 1992, Filippi & Luiselli 2004). Their global distribution of follow the Steppe biom with extensions to other grasslands, in Europe these snakes are present in the Western Alps & Appenines (Vipera ursinii ursinii), Dinarides (Vipera ursinii macrops) and Hellenides (Vipera graeca) mountain ranges; and the Pannonian (Vipera ursinii rakosiensis) and Bessarabian (Vipera ursinii moldavica) lowlands, plains (Mizsei et al. -

Strasbourg, 22 May 2002

Strasbourg, 21 October 2015 T-PVS/Inf (2015) 18 [Inf18e_2015.docx] CONVENTION ON THE CONSERVATION OF EUROPEAN WILDLIFE AND NATURAL HABITATS Standing Committee 35th meeting Strasbourg, 1-4 December 2015 GROUP OF EXPERTS ON THE CONSERVATION OF AMPHIBIANS AND REPTILES 1-2 July 2015 Bern, Switzerland - NATIONAL REPORTS - Compilation prepared by the Directorate of Democratic Governance / The reports are being circulated in the form and the languages in which they were received by the Secretariat. This document will not be distributed at the meeting. Please bring this copy. Ce document ne sera plus distribué en réunion. Prière de vous munir de cet exemplaire. T-PVS/Inf (2015) 18 - 2 – CONTENTS / SOMMAIRE __________ 1. Armenia / Arménie 2. Austria / Autriche 3. Belgium / Belgique 4. Croatia / Croatie 5. Estonia / Estonie 6. France / France 7. Italy /Italie 8. Latvia / Lettonie 9. Liechtenstein / Liechtenstein 10. Malta / Malte 11. Monaco / Monaco 12. The Netherlands / Pays-Bas 13. Poland / Pologne 14. Slovak Republic /République slovaque 15. “the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia” / L’« ex-République yougoslave de Macédoine » 16. Ukraine - 3 - T-PVS/Inf (2015) 18 ARMENIA / ARMENIE NATIONAL REPORT OF REPUBLIC OF ARMENIA ON NATIONAL ACTIVITIES AND INITIATIVES ON THE CONSERVATION OF AMPHIBIANS AND REPTILES GENERAL INFORMATION ON THE COUNTRY AND ITS BIOLOGICAL DIVERSITY Armenia is a small landlocked mountainous country located in the Southern Caucasus. Forty four percent of the territory of Armenia is a high mountainous area not suitable for inhabitation. The degree of land use is strongly unproportional. The zones under intensive development make 18.2% of the territory of Armenia with concentration of 87.7% of total population. -

The Secret Life of the Adder (Vipera Berus) Revealed Through Telemetry

The Glasgow Naturalist (2018) Volume 27, Supplement. The Amphibians and Reptiles of Scotland The secret life of the adder (Vipera berus) revealed through telemetry N. Hand Central Ecology, 45 Albert Road, Ledbury HR8 2DN E-mail: [email protected] INTRODUCTION 4. The data inform landscape management I have radio-tracked the movements of European beneficial to snakes. adder (Vipera berus) populations on six sites in central and southern England since 2010, using RESULTS telemetry of tagged snakes (Fig. 1A). During eight I first tested whether externally attached telemetry years of tracking projects, 75 snakes have been tags would affect snake behaviour. In 2010 a tag was successfully fitted with external tags and their tested on an adult male for 15 days and activity movements mapped. monitored. In this time the adder was observed basking and moving as expected, with the tag not impeding progress. Tagged snakes have subsequently been recorded in combat, courtship, copulation, basking, and exhibiting evidence of prey ingestion (Fig. 2). Fig. 1. Telemetry tags used to monitor the movements of adders (Vipera berus). Position of a tag on an adult female (A). Tags are fitted with surgical tape low down the body, avoiding the widest body area. The tape does not go entirely around the body but only a small section applied to the flank. Tags are typically sloughed off on cast skin and Fig. 2. Adder (Vipera berus) behaviour was unaffected by retrieved whilst still transmitting (B). (Photos: N. Hand) telemetry tags. A number of tagged snakes have been observed having caught and ingested prey items (A). -

Vipera Aspis) Envenomation: Experience of the Marseille Poison Centre from 1996 to 2008

Toxins 2009, 1, 100-112; doi:10.3390/toxins1020100 OPEN ACCESS toxins ISSN 2072-6651 www.mdpi.com/journal/toxins Article Asp Viper (Vipera aspis) Envenomation: Experience of the Marseille Poison Centre from 1996 to 2008 Luc de Haro *, Mathieu Glaizal, Lucia Tichadou, Ingrid Blanc-Brisset and Maryvonne Hayek-Lanthois Centre Antipoison, hôpital Salvator, 249 boulevard Sainte Marguerite, 13009 Marseille, France; E-Mails: [email protected] (M.G.); [email protected] (L.T.); [email protected] (I.B.-B.); [email protected] (M.H.-L.) * Author to whom correspondence should be addressed; E-Mail: [email protected]. Received: 9 October 2009; in revised form: 18 November 2009 / Accepted: 23 November 2009 / Published: 24 November 2009 Abstract: A retrospective case review study of viper envenomations collected by the Marseille’s Poison Centre between 1996 and 2008 was performed. Results: 174 cases were studied (52 grade 1 = G1, 90 G2 and 32 G3). G1 patients received symptomatic treatments (average hospital stay 0.96 day). One hundred and six (106) of the G2/G3 patients were treated with the antivenom Viperfav* (2.1+/-0.9 days in hospital), while 15 of them received symptomatic treatments only (plus one immediate death) (8.1+/-4 days in hospital, 2 of them died). The hospital stay was significantly reduced in the antivenom treated group (p < 0.001), and none of the 106 antivenom treated patients had immediate (anaphylaxis) or delayed (serum sickness) allergic reactions. Conclusion: Viperfav* antivenom was safe and effective for treating asp viper venom-induced toxicity. -

Serpent Iconography Kristen Lee Hostetler

Etruscan Studies Journal of the Etruscan Foundation Volume 10 Article 16 2007 Serpent Iconography Kristen Lee Hostetler Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/etruscan_studies Recommended Citation Hostetler, Kristen Lee (2007) "Serpent Iconography," Etruscan Studies: Vol. 10 , Article 16. Available at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/etruscan_studies/vol10/iss1/16 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Etruscan Studies by an authorized editor of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Serpent Iconography by Kristen Lee Hostetler ew creatures are as rich in iconographicaL symboLism as the serpent. In fact, their ven - eration is an aLmost universaL aspect of cuLtures past and present. Cross-cuLturaLLy, ser - Fpents symboLize fertiLity, immortaLity, wisdom, and prosperity. Due to their subter - ranean Lairs and poisonous venom, they aLso became associated with death and the under - worLd, taKing on aspects of ancestors, ghosts, and guardians. An important aspect of serpent symboLism is its reLationship with Life, death, and the underworLd. As man saw the serpent emerging from darK recesses and rocKy niches, he imagined it as the guardian of the earth, protecting whatever was pLaced within the ground. As a sexuaL symboL, anaLogous to the maLe member, it became connected with prosperity and Life. With the abiLity to shed its sKin, the serpent appears to renew its youth and increase its strength. This observation Led to asso - ciations with youth, wisdom, heaLth, immortaLity. FinaLLy, the venom of the serpent must have been infamous.