The Newspaper PM, New York 1940-1942

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pressemappe American Photography

Exhibition Facts Duration 24 August – 28 November 2021 Virtual Opening 23. August 2021 | 6.30 PM | on Facebook-Live & YouTube Venue Bastion Hall Curator Walter Moser Co-Curator Anna Hanreich Works ca. 180 Catalogue Available for EUR EUR 29,90 (English & German) onsite at the Museum Shop as well as via www.albertina.at Contact Albertinaplatz 1 | 1010 Vienna T +43 (01) 534 83 0 [email protected] www.albertina.at Opening Hours Daily 10 am – 6 pm Press contact Daniel Benyes T +43 (01) 534 83 511 | M +43 (0)699 12178720 [email protected] Sarah Wulbrandt T +43 (01) 534 83 512 | M +43 (0)699 10981743 [email protected] 2 American Photography 24 August - 28 November 2021 The exhibition American Photography presents an overview of the development of US American photography between the 1930s and the 2000s. With works by 33 artists on display, it introduces the essential currents that once revolutionized the canon of classic motifs and photographic practices. The effects of this have reached far beyond the country’s borders to the present day. The main focus of the works is on offering a visual survey of the United States by depicting its people and their living environments. A microcosm frequently viewed through the lens of everyday occurrences permits us to draw conclusions about the prevalent political circumstances and social conditions in the United States, capturing the country and its inhabitants in their idiosyncrasies and contradictions. In several instances, artists having immigrated from Europe successfully perceived hitherto unknown aspects through their eyes as outsiders, thus providing new impulses. -

Street Seen Teachers Guide

JAN 30–APR 25, 2010 THE PSYCHOLOGICAL GESTURE IN AMERICAN PHOTOGRAPHY, 1940–1959 TEACHERS GUIDE CONTENTS 2 Using This Teachers Guide 3 A Walk through Street Seen 10 Vocabulary 11 Cross-Curricular Activities 15 Lesson Plan 18 Further Resources cover image credit Ted Croner, Untitled (Pedestrian on Snowy Street), 1947–48. Gelatin silver print, 14 x 11 in. Howard Greenberg Gallery, New York. ©Ted Croner Estate prepared by Chelsea Kelly, School & Teacher Programs Manager, Milwaukee Art Museum STREET SEEN: The Psychological Gesture in American Photography, 1940–1959 TEACHERS GUIDE 1 USING THIS TEACHERS GUIDE This guide, intended for teachers of grades 6–12, is meant to provide background information about and classroom implementation ideas inspired by Street Seen: The Psychological Gesture in American Photography, 1940–1959, on view at the Milwaukee Art Museum through April 25, 2010. In addition to an introductory walk-through of the exhibition, this guide includes useful vocabulary, discussion questions to use in the galleries and in the classroom, lesson ideas for cross-curricular activities, a complete lesson plan, and further resources. Learn more about the exhibition at mam.org/streetseen. Let us know what you think of this guide and how you use it. Email us at [email protected]. STREET SEEN: The Psychological Gesture in American Photography, 1940–1959 TEACHERS GUIDE 2 A WALK THROUGH STREET SEEN This introduction follows the organization of the exhibition; use it and the accompanying discussion questions as a guide when you walk through Street Seen with your students. Street Seen: The Psychological Gesture in American Photography, 1940–1959 showcases the work of six American artists whose work was directly influenced by World War II. -

Beloved Holiday Movie: How the Grinch Stole Christmas! 12/9

RIVERCREST PREPARATORY ONLINE SCHOOL S P E C I A L I T E M S O F The River Current INTEREST VOLUME 1, ISSUE 3 DECEMBER 16, 2014 We had our picture day on Beloved Holiday Movie: How the Grinch Stole Christmas! 12/9. If you missed it, there will be another opportunity in the spring. Boris Karloff, the voice of the narrator and the Grinch in the Reserve your cartoon, was a famous actor yearbook. known for his roles in horror films. In fact, the image most of us hold in our minds of Franken- stein’s monster is actually Boris Karloff in full make up. Boris Karloff Jan. 12th – Who doesn’t love the Grinch Winter Break is Is the reason the Grinch is so despite his grinchy ways? The Dec. 19th popular because the characters animated classic, first shown in are lovable? We can’t help but 1966, has remained popular with All class work must adore Max, the unwilling helper of children and adults. be completed by the Grinch. Little Cindy Lou Who The story, written by Dr. Seuss, the 18th! is so sweet when she questions was published in 1957. At that the Grinch’s actions. But when the I N S I D E time, it was also published in Grinch’s heart grows three sizes, THIS ISSUE: Redbook magazine. It proved so Each shoe weighed 11 pounds we cheer in our own hearts and popular that a famous producer, and the make up took hours to sing right along with the Whos Sports 2 Chuck Jones, decided to make get just right. -

Coney Island: Visions of an American Dreamland, 1861–2008 Jan

Coney Island: Visions of an American Dreamland, 1861–2008 Jan. 31 – May 31, 2015 Exhibition Checklist DOWN AT CONEY ISLE, 1861-94 1. Sanford Robinson Gifford The Beach at Coney Island, 1866 Oil on canvas 10 x 20 inches Courtesy of Jonathan Boos 2. Francis Augustus Silva Schooner "Progress" Wrecked at Coney Island, July 4, 1874, 1875 Oil on canvas 20 x 38 1/4 inches Manoogian Collection, Michigan 3. John Mackie Falconer Coney Island Huts, 1879 Oil on paper board 9 5/8 x 13 3/4 inches Brooklyn Historical Society, M1974.167 4. Samuel S. Carr Beach Scene, c. 1879 Oil on canvas 12 x 20 inches Smith College Museum of Art, Northampton, Massachusetts, Bequest of Annie Swan Coburn (Mrs. Lewis Larned Coburn), 1934:3-10 5. Samuel S. Carr Beach Scene with Acrobats, c. 1879-81 Oil on canvas 6 x 9 inches Collection Max N. Berry, Washington, D.C. 6. William Merritt Chase At the Shore, c. 1884 Oil on canvas 22 1/4 x 34 1/4 inches Private Collection Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art Page 1 of 19 Exhibition Checklist, Coney Island: Visions of an American Dreamland, 1861 – 2008 12-15-14-ay 7. John Henry Twachtman Dunes Back of Coney Island, c. 1880 Oil on canvas 13 7/8 x 19 7/8 inches Frye Art Museum, Seattle, 1956.010 8. William Merritt Chase Landscape, near Coney Island, c. 1886 Oil on panel 8 1/8 x 12 5/8 inches The Hyde Collection, Glens Falls, N.Y., Gift of Mary H. Beeman to the Pruyn Family Collection, 1995.12.7 9. -

Sandra Weiner: New York Kids, 1940-1948 Exhibition: June 7Th – July 27Th, 2018 Opening Reception: June 7Th, 2018, 6 – 8 PM

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Sandra Weiner: New York Kids, 1940-1948 Exhibition: June 7th – July 27th, 2018 Opening Reception: June 7th, 2018, 6 – 8 PM Steven Kasher Gallery is pleased to present Sandra Weiner: New York Kids, 1940-1948. The exhibition features over twenty rare vintage black and white prints, many exhibited for the first time. Weiner’s photographs are celebrated for their perceptive depiction of everyday life in New York City's close-knit neighborhoods of the 1940s. Her photographs of children at play create a palpable sense of place. Weiner’s photographs reveal random moments of grace, transforming social documentation into a broadly humanist mode of street photography. Her sensitive and subtle renderings of neighborhood atmosphere make her photographs of New York heartwarming. Also on view is the exhibition Dan Weiner: Vintage New York, 1940-1959. This is the first time that exhibitions of the husband and wife photographers have been on view concurrently. Weiner focused on New York’s poorer children, possibly because she identified with them but more so because she wanted to tell a story of perseverance and hope. Weiner’s work highlighted social concerns of the era, however she focused her lens specifically on the city’s youngest denizens. For Weiner, children surviving the rough-and-tumble city streets became a symbol of fortitude. She strolled the city’s streets or posted at the edge of vacant lots where children play and caught them absorbed in their own worlds. Included in the exhibition is an extended essay in which Weiner followed a young boy named Mickey through his daily life in the tenements of East 26th Street. -

Oral History Interview with Jerome Liebling, 2010 Sept. 17

Oral history interview with Jerome Liebling, 2010 Sept. 17 Funding for this interview was provided by the Brown Foundation. Contact Information Reference Department Archives of American Art Smithsonian Institution Washington. D.C. 20560 www.aaa.si.edu/askus Transcript Preface The following oral history transcript is the result of a recorded interview with Jerome Liebling on September 17, 2010. The interview took place in Amherst, Massachusetts, and was conducted by Robert Silberman for the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. The Archives of American Art has reviewed the transcript and has made corrections and emendations. This transcript has been lightly edited for readability by the Archives of American Art. The reader should bear in mind that they are reading a transcript of spoken, rather than written, prose. Interview ROBERT SILBERMAN: This is Robert Silberman interviewing Jerome Liebling at the artist's home in Amherst, Massachusetts on September 17th, 2010 for the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, card number one. Good morning, Jerry. Maybe we could begin by my asking you when and where were you born. JEROME LIEBLING: New York City, April 16th, 1924. New York City, of course, has many boroughs. I was born in Manhattan. In fact, I was born in Harlem. At the time, that's where my family lived. And soon moved to Brooklyn. ROBERT SILBERMAN: Could you describe your childhood and your family background a little? JEROME LIEBLING: Interesting, in contemplating your arrival and finding a form to talk about my childhood— [phone rings]—in contemplating my childhood, there are certain terms that I think are important and when I had learned about these terms, would help define my childhood. -

The Radical Camera: New York's Photo League, 1936-1951 a N ED

The Jewish Museum TheJewishMuseum.org 1109 Fifth Avenue [email protected] AN EDUCATOR’S RESOURCE New York, NY 10128 212.423.5200 Under the auspices of The Jewish Theological Seminary teachers. These materials can be used to supplement and enhance enhance and supplement to used be can materials These teachers. students’ ongoing studies. This resource was developed for elementary, middle, and high school school high and middle, elementary, for developed was resource This 1936-1951 New York’s Photo League, York’s New The Camera: Radical Acknowledgments This educator resource was written by Lisa Libicki, edited by Michaelyn Mitchell, and designed by Olya Domoradova. At The Jewish Museum, Nelly Silagy Benedek, Director of Education; Michelle Sammons, Educational Resources Coordinator; and Hannah Krafcik, Marketing Assistant, facilitated the project’s production. Special thanks to Dara Cohen-Vasquez, Senior Manager of School Programs and Outreach; Mason Klein, Curator; and Roger Kamholz, Marketing Editorial Manager, for providing valuable input. These curriculum materials were inspired by the exhibition The Radical Camera: New York’s Photo League, 1936-1951 on view at The Jewish Museum November 4, 2011–March 25, 2012. This resource is made possible by a generous grant from the Kekst Family. PHOTO LEAGUE: an EDUCator’S guIDE ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 2 Introduction Overview members were inspired by this social climate to make inequity and discrimination a subject of their work. The Photo League was a New York City–based organization of professional and amateur photographers. A splinter group The early 1940s witnessed the country’s rapid transition from of the Film and Photo League, it was founded in 1936 by New Deal recovery to war mobilization. -

SEUSSICAL This December, W.F. West Theatre Continues Its Tradition

SEUSSICAL This December, W.F. West Theatre continues its tradition of bringing children’s theatre to our community when we present: Seussical. The amazing world of Dr. Seuss and his colorful characters come to life on stage in this musical for all ages. The Cat in the Hat takes us through the story of Horton the Elephant and his quest to prove that Whos really do exist. The story: A young boy, JoJo, discovers a red-and-white-striped hat. The Cat in the Hat suddenly appears and brings along with him Horton the Elephant, Gertrude McFuzz, the Whos, Mayzie La Bird and Sour Kangaroo. Horton hears a cry for help. He follows the sound to a tiny speck of dust floating through the air and realizes that there are people living on it. They are so small they can't be seen – the tiny people of Whoville. Horton places them safely onto a soft clover. Sour Kangaroo thinks Horton is crazy for talking to a speck of dust. As Horton is left alone with his clover, the Cat thrusts Jojo into the story. Horton discovers much more about the Whos and their tiny town of Whoville while Jojo's imagination gets the better of him. Horton and Jojo hear each other and become friends when they realize their imaginations are so much alike. Gertrude writes love songs about Horton. She believes Horton doesn't notice her because of her small tail. Mayzie appears with her Bird Girls and offers Gertrude advice which leads her to Doctor Dake and his magic pills for “amayzing” feathers. -

Modern American Grotesque

Modern American Grotesque Goodwin_Final4Print.indb 1 7/31/2009 11:14:21 AM Goodwin_Final4Print.indb 2 7/31/2009 11:14:26 AM Modern American Grotesque LITERATURE AND PHOTOGRAPHY James Goodwin THEOHI O S T A T EUNIVER S I T YPRE ss / C O L U MB us Goodwin_Final4Print.indb 3 7/31/2009 11:14:27 AM Copyright © 2009 by The Ohio State University. All rights reserved. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Goodwin, James, 1945– Modern American grotesque : Literature and photography / James Goodwin. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13 : 978-0-8142-1108-3 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN-10 : 0-8142-1108-9 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN-13 : 978-0-8142-9205-1 (cd-rom) 1. American fiction—20th century—Histroy and criticism. 2. Grotesque in lit- erature. 3. Grotesque in art. 4. Photography—United States—20th century. I. Title. PS374.G78G66 2009 813.009'1—dc22 2009004573 This book is available in the following editions: Cloth (ISBN 978-0-8142-1108-3) CD-ROM (ISBN 978-0-8142-9205-1) Cover design by Dan O’Dair Text design by Jennifer Shoffey Forsythe Typeset in Adobe Palatino Printed by Thomson-Shore, Inc. The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials. ANSI Z39.48–1992. 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Goodwin_Final4Print.indb 4 7/31/2009 11:14:28 AM For my children Christopher and Kathleen, who already possess a fine sense of irony and for whom I wish in time stoic wisdom as well Goodwin_Final4Print.indb 5 7/31/2009 -

Extra ORDINARY Photographic Perspectives on Everyday Life

DOSSIER PRESSE © Lisette Model, Femme à la voilette, San Francisco, 1949-courtesy Baudoin Lebon extra ORDINARY Photographic perspectives on everyday life Exhibitions, workshops, events 12 October — 15 December 2019 INSTITUT POUR LA PHOTOGRAPHIE INSTITUT POUR LA PHOTOGRAPHIE extraORDINAIRE, regards photographiques sur le quotidien On 11 October 2019, the Institut pour la photographie will inaugurate its first cultural programme on in Lille with extraORDINARY: Photographic perspectives on everyday life. Seven exhibitions, an installation open to the public, as well as events and experimental workshops, will cover the history of photography from the end of the 19th century to today. This new programme reflects different photographic approaches and styles, with a selection of works from around the world that explore everyday life and its banality. DOSSIER PRESSE Throughout her career, photographer Lisette Model never ceased to affirm the importance of the individual perspective, in both her work and her teaching. The Institut pour la photographie pays tribute to her with a new exhibition bringing together four great figures of American photography around of her work: Leon Levinstein, Diane Arbus, Rosalind Fox Solomon and Mary Ellen Mark. Since 2017, Laura Henno has immersed herself in the lost city of Slab City in the heart of the Californian desert. The Institute supports the artist, who comes from the Region, with the production of previously unpublished prints for this new exhibition project Radical Devotion. Thomas Struth gives us a glimpse of our relationship to everyday life through a documentary approach that is carefully crafted to reveal the complexity of the ordinary. Begun in 1986, his psychological and sociological portraits of families revisit the traditional genre of family portraiture. -

Seussical Jr AUDITION PACKET

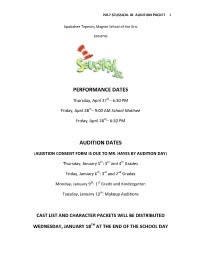

2017 SEUSSICAL JR. AUDITION PACKET 1 Apalachee Tapestry Magnet School of the Arts presents PERFORMANCE DATES Thursday, April 27th– 6:30 PM Friday, April 28th– 9:00 AM School Matinee Friday, April 28th– 6:30 PM AUDITION DATES (AUDITION CONSENT FORM IS DUE TO MR. HAYES BY AUDITION DAY) Thursday, January 5th: 5th and 4th Grades Friday, January 6th: 3rd and 2nd Grades Monday, January 9th: 1st Grade and Kindergarten Tuesday, January 10th: Makeup Auditions CAST LIST AND CHARACTER PACKETS WILL BE DISTRIBUTED WEDNESDAY, JANUARY 18TH AT THE END OF THE SCHOOL DAY 2017 SEUSSICAL JR. AUDITION PACKET 2 INTRODUCTION Your son or daughter is interested in participating in this year’s musical, “Seussical Jr,” on April 27th and 28th, 2017 at Apalachee Tapestry Magnet School of the Arts. This show provides a great opportunity for all interested students to work together, regardless of experience or grade level! It also is a big undertaking, and we need to know that the students who choose to participate will be able to commit to the time and attention required. Please read through this packet and do not hesitate to contact Mr. Hayes ([email protected]) if you have any questions. AUDITION REQUIREMENTS ü Choose one character from the audition packet and memorize that character’s monologue and song. Song clips can be found on Mr. Hayes’ website under “Important Documents.” ü Read through and complete the attached Audition Consent form. THIS MUST BE RETURNED BY THE CHILD’S AUDITION DAY. ü Parents must attend the MANDATORY Parent Meeting: JANUARY 23RD 6:30 PM. -

Fhnews Oct20

Forest Hill News October 2020 Forest Hill News—Page 1 THEODOR GEISEL The young man, Theodor Geisel, was already a successful illustrator and cartoonist in New York, but he wanted to be an author. So, Theodor wrote a book which he enthusiastically submitted to a publisher. It was rejected. And that rejection was followed by another, and another, and another. There were twenty-seven in all. No one likes to be rejected. Theodor lost his enthusiasm. Walking along Madison Avenue with the unwanted manuscript under his arm, it was Theodor’s intention to burn it as soon as he returned to his apartment. Whether it was providential or serendipitous doesn’t matter, but it mattered a lot that on his walk home Theodor happened to run into Mike McClintock, an old friend from student years at Dartmouth College. The friends chatted, but before going their separate ways Geisel’s friend inquired what was in that big bundle tucked under his arm. After pouring out his sad story of serial rejections, the friend announced that he had recently been hired as the Children’s Book Editor for Vanguard Press, and he was on his way to his office for his first day on the job, and if Geisel wanted to accompany him he would be quite willing to look at the oft rejected manuscript. The novitiate editor recognized the manuscript as something quite different for a children’s book, almost “off the wall,” but he liked what he saw, both in the text and the wild illustrations. The book, And to Think What I Saw on Mulberry Street, first published in 1937, was an immediate best seller.