Nysba Fall 2006 | Vol

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Woods to Purchasejbond Issue Edsel Ford. Estate

SAVE, FOOD TO THE NEWS HAS MO~D. , HELP FEED COME SEEUS IN OUR , 'P • NEW BUilDING, UNDER THE WORLD'S. ~Grosse 01 .News THE ELM AT 99 STARVING PEOPLE nte Complet~ News Coverag~ of. All the Pointes KERCHEVAL f VOLUME 7~O. 32 GROSSE POINTE, MICHIGAN. AUGUST a. 19% $2.00 Per Year-5c Per Copy Fully Paid Circulation ETTER STREEtS ARE ON THE WAY! - i;,~...... -------- .. 1 Park Youngster Sets Record.in Soap Box Derby tIIEADLINES. Woods To PurchaseJBond Issue ~ of IN ~.. WEEK I :. Edsel Ford. Estate t 'As CMllpiW ", IN ~1:3~~.~~~ ~.. G1'OIS' PoitU. Newl "-1: . List Shows How M~ney Is to i ...ThllJ'ldaT. AapsL 1 For Par k on Lake 8e Spent; Projects Lis{ed ltNRY J'ORD n &oswers Wlllt- I I d in Full for Readers erl:tWther'a invitation addre&$ed Date for Special E ection at Which Voters Wi! Deci e on to &1tomoblle manufacturers to I!t Bond .Issues to Be Named Next Monday The City of Grosse Pointe at i round table and d!:;eus waYs . has sold i'ts $300,000. bond is. and me&11I to increue production The Woods village ComnusslOners have decld~d, ~o go I. sue, authorized, by the voters .:!FOrd say. noth1Dc dolllC unW through with the purchase of the 43.7 acres of the ~dsel, to inaugurate a general, streP.t .t.rlies in 18 partI plantl which '11 d' thr.ten ~to ahut down p~uetlon Ford estate for a lake front park for the village and they WI repair an paving program, In lord a.re first o!ettJed ••. -

Declarations-Part 1

, ";IV..JULU ;......... '''' -..... iJ 111 ~ ~, CONOOPlIl'IIU!1 DECLARATION GOLDeN RI DGE. CONOOH IN! UHS WDeX Title Section No. Page No. Submis.;on to Condominium CMnersh!p, .............. 1 ........... C1!!finitions •••••• ~~.~ •• ~. ~" •• _ ~ ~ •• ,,~ ••• ~~ ••• ~. ~.# .2. ~ ..... 6.,."" Divi.ion of Property in the Condominium Units and Conveyance of Unit6 ••••.•••...••....• 3 .••.• $ •••• ~. 3 Limited Common Element5 ••••• ~.6 ••• " •••••••• 4" •••••• 4."' ........... 4; Description of Condcninium Unit •• W ...... H •••• ~.H.S ........ "'.H ... '" Condom!n!= ~ap ................................... 6 ............ 5 lnsepl'lt'Jibility of a Condominium Unit. •••• " ......... 7 •• ~ .......... " 5 Repsrate Assersment and Taxation - Noticb' to A5sesBor .............................. 6 •••••••••••• 6 Porm of O\tnership - Title ...... ~ ... ~ •••••••• ~ ••••••. 9 ....... ~.~ •• ~ 6 Non-Pr.rtitionability Bnd Transfer of. ~mrncn element.~~ ......... ~ ... ., •• e ......... * ••••• ~10 .. .,~~~ .... ~ .. " .... 6 Common Ele1lent.5 .............. ~ ............. ~ ......... ,,~ .. 11 .............. ~ .. 6 Use and Occupancy .............................. $ ........................ 12 ..... , " .. .. .. .. .. .... 6 Ea8ements ........................................... 1) .• ~ ..... ., .. ~ .. 7 Termination of Mechanlc l g Lien Rights and Indemnification •••••••••••••....•.. 14 .••••••••••• S C-olden Ridge CondGnliiniurt Association, IfiC ••••• q .. j5 •• ~ ............ "' ... 8 Re8ervation for Access - Maintenance, Repair Bnd Emergenciea~"'""'~~~,.~"' -

2005 Annual Report on the New York City Property

The City of New York • Department of Finance • Office of Tax Policy Michael R. Bloomberg • Mayor Martha E. Stark • Commissioner ANNUAL REPORT ON THE NYC REAL PROPERTY TAX Fiscal Year 2005 MICHAEL R. BLOOMBERG MAYOR MARTHA E. STARK COMMISSIONER REPORT PREPARED BY THE OFFICE OF TAX POLICY AUGUST 2005 Table of Contents Fast Facts ………………………………………………………………………. i Highlights ………………………………………………………………………. ii Part I. Current Year Profiles …………………………………………. 1 Market and Assessed Value by Property Type ………………………….. 1 Exempt Value by Property Type ………………………………………... 7 Exemptions by Exemption Type ………………………………………… 13 Part II. Tax Levy ………………………………………………………… 25 Reconciliation of Assessment Roll, Tax Levy and Net Levy Billed ……. 27 Abatements by Property Type and Abatement Type ……………………. 28 Part III. Office Buildings ………………………………………………… 29 Part IV. Home Sales ……………………………………………………… 33 Part V. Cooperative and Condominium Tax Abatement Program ….. 35 Part VI. Delinquencies …………………………………………………… 36 Part VII. Building Permits ………………………………………………... 39 Part VIII. Historical Data ………………………………………………….. 41 Market Value by Tax Class and Borough FY 1993 – 2005 ……………… 41 Assessed Value by Tax Class FY 1991 – 2005 ………………………….. 42 Taxable Billable Assessed Value by Borough FY 1991 – 2005 ………… 43 Tax Levy by Tax Class FY 1991 – 2005 …………………………………. 44 Tax Rates FY 1991 – 2005 ……………………………………………….. 45 Tax Levy and Revenue FY 1991 – 2005 ………………………………….. 46 Unused Operating Margin FY 1991 – 2005 ……………………………… 47 Appendix ………………………………………………………………………… 48 The Real Property Tax -

Condominiums and Cooperatives

NYC Living: Coops and Condos HEIBERGER SDK ATTORNEYS AT LAW OFFERED BY: RE CREDITS, LLC PRESENTED BY: JAMIE HEIBERGER, ESQ SDK HEIBERGER, LLP 205 East 42nd St., 6th Floor, New York, NY 10017 475 Port Washington Blvd Port Washington, NY 11050 Direct: 212.532.2067 Mobile: 917.697.5853 1 Overview • Cooperative Apartment • Ownership • Due diligence • Board approval • Subletting • Loan documents in a co-op lendingHEIBERGER transaction • Condominium SDK ATTORNEYS AT LAW • Ownership of a condo unit • Condo waiver of Right of First Refusal • New Development Projects • Townhouses • Characteristics • Engineers Inspection • Legal Aspects • Due Diligence 2 HEIBERGER SDK ATTORNEYS AT LAW Co-Operatives 3 Form of Ownership • A cooperative corporation owns the real estate (land, buildings, and property rights and all interests). • title to the property, as shown on the deed, is in the name of the corporation • The ownership interest in a co-op is evidenced by shares of stock. • Ownership of cooperative stockHEIBERGER is essentially the same as stock in corporationsSDK such as Microsoft,ATTORNEYS Facebook, Yahoo, AT etc. LAW • However, accompanying the shares of stock in a cooperative is a proprietary lease granting the right of the shareholders to reside in a particular apartment. • Leasehold Coops (a Co-Op with a ground lease) 4 Proprietary lease- what does it mean to owners? • Rights and obligations included in proprietary lease and corporation bylaws • Receive proprietary lease • long-term lease or estate for years • Receive stock certificates HEIBERGER SDK ATTORNEYS AT LAW 5 Due Diligence • Financial Statements: • Each shareholder of the corporation is obligated to pay monthly maintenance charges which are aggregated and used to pay all costs and expenses in operating and maintaining the building. -

Listing Appointment Checklist

75-hour New York Prelicense Course Syllabus Course Description This Pre-License course focuses on New York Real Estate Law and the everyday practice of Real Estate approved by the New York Real Estate Commission. This course covers all the subjects mandated by New York Real Estate License Law, for those interested in gaining their license. This course is expressly designed for, and geared to, all those potential licensees as defined by the New York Real Estate Commission, for the purpose of sitting for the real estate salesperson's exam. Anyone who assists or desires to assist others in the sale, leasing, management, or exchange of real estate must hold at least a real estate salesperson's license. Course Learning Objectives Unit 1: License Law Overview and Procedures for Licensing 1. State the purpose of the NY licensing law, the Department of State and the Board of Real Estate. 2. Explain the rules for obtaining a license in New York, state the types of licenses and their respective requirements. 3. Explain the New York real estate licensing exam requirements, procedures and policies. Unit 2: License Law Rules and Regulations 1. Define and explain the rules for license issuance, license information changes and branch office management. 2. Define and explain the rules for license renewal, continuing education and reciprocity. 3. Identify at least five Department regulations including handling of kickbacks and proper advertising. Unit 3: Unlicensed Assistants and License Law Violations 1. Name three allowed and three prohibited activities for unlicensed assistants and list at least five licensee activities that violate NY license law. -

NYS TEST STUDY GUIDE Exam

ABSTRACT This is a proprietary study guide created by the Alexander Anderson Center for Real Estate Education. This guide is intended for New Jersey real estate agents who wish to take their New York State real estate license NYS TEST STUDY GUIDE exam. Written by Coura For New Jersey Real Estate Agents Gaye-Sow Edited by Noelle Frieson Copyright © 2020 by the Alexander Anderson Center for Real Estate Education All rights reserved. No part of this document may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher. First, Congratulations! You are taking the first steps towards becoming a dual licensed agent in both New Jersey and New York states. To take your New York State exam you must mail in the necessary forms for your New York Real Estate Education Waiver along with your certificate of completion from your original real estate school. The NY forms are located in the back of this book. Please read all of the requirements and directions provided by New York State before sending in the forms. Upon successful completion of the NY required steps you will receive an education waiver which will allow you to take the NY State exam. Please note, you must be a licensed NJ real estate agent before you can request the education waiver for New York State. This packet contains the following: • A study packet for the NYS State Test. We here at the Center for Real Estate Education have compiled out the information from the NYS text book that is NYS specific. -

Manchester, Vermont July 11 – 14, 2019 Equinox Golf Resort & Spa Manchester, VT Real Property Law Section Chair Gerard G

NEW YORK STATE BAR ASSOCIATION REAL PROPERTY LAW SECTION 9.0 MCLE Credits First-time Real Property Law Section Summer attendees enjoy a 50% discount for attorney meeting registration. You must be a member of the NYSBA RPLS to take advantage of this special offer. If you are not a member of NYSBA or the RPLS section you can become one by calling our Member Resource Center 800.582.2452. Summer Meeting Manchester, Vermont July 11 – 14, 2019 Equinox Golf Resort & Spa Manchester, VT www.nysba.org/RealSummer2019 Real Property Law Section Chair Gerard G. Antetomaso, Esq., Evans Fox LLP, Rochester, NY Program Chair Ira S. Goldenberg, Esq., Goldenberg & Selker, LLP, White Plains, NY TOTAL CLE CREDITS: Under New York’s MCLE rule, this program has been approved for a total of 9.0 MCLE credits consisting of 6.0 in Areas of Professional Practice, 2.0 in Ethics and 1.0 credit in Diversity, Inclusion and Elimination of Bias for experienced attorneys. Attorneys admitted 2 years or less are not eligible to receive credit in the Diversity, Inclusion and Elimination of Bias category. This program is not transitional and does not qualify for newly admitted attorneys. Hotel Information Equinox Golf Resort & Spa Manchester, VT The Equinox, a Luxury Collection Golf Resort & Spa is tucked into the Green Mountains in the picturesque town of Manchester, Vermont. The resort offers a definitive hospitality experience in southern Vermont with impeccable service and the latest in modern conveniences and amenities. A room block has been reserved for attendees of the RPLS Summer Meeting. -

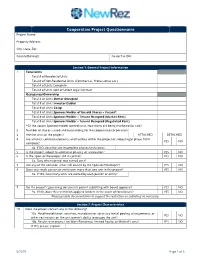

Cooperative Project Questionnaire Project Name

Cooperative Project Questionnaire Project Name: Property Address: City, State, Zip: County/Borough: Co-op Tax ID#: Section 1: General Project Information 1 Total Units Total # of Residential Units Total # of Non-Residential Units (Commercial, Professional, etc.) Total # of Units Complete Total # of Units Sold or Under Legal Contract Occupancy/Ownership Total # of Units Owner Occupied Total # of Units Investor/Sublet Total # of Units Co-op Total # of Units Sponsor/Holder of Unsold Shares – Vacant* Total # of Units Sponsor/Holder – Tenant Occupied (Market Rent) Total # of Units Sponsor/Holder – Tenant Occupied (Regulated Rent) *Of the vacant Sponsor/Holder owned units, how many are being marketed for sale? 2 Number of shares issued and outstanding for the cooperative corporation? 3 Are the units of the project? ATTACHED DETACHED 4 Are all units, common elements, and facilities within the project or subject legal phase 100% YES NO complete? 4a. If NO, describe any incomplete phases/units/areas: 5 Is the project subject to additional phasing or annexation? YES NO 6 Is the Sponsor/Developer still in control? YES NO 6a. Date when control was turned over? 7 Are any of the common areas still owned by the Sponsor/Developer? YES NO 8 Does any single person or entity own more than one unit in the project? YES NO 8a. If YES, how many units are owned by each person or entity? 9 Do the project’s governing documents permit subletting with board approval? YES NO 9a. If NO, does this restriction apply to lenders in the event of foreclosure? YES NO Please provide documentation to support the restriction on subletting as necessary. -

Supreme Court, Appellate Division First Department

SUPREME COURT, APPELLATE DIVISION FIRST DEPARTMENT JUNE 27, 2013 THE COURT ANNOUNCES THE FOLLOWING DECISIONS: Gonzalez, P.J., Mazzarelli, Moskowitz, Renwick, Manzanet-Daniels, JJ. 9862 Raymond Alberto Carreras, et al., Index 17848/05 Plaintiffs-Respondents, -against- Morrisania Towers Housing Company Limited Partnership, et al., Defendants-Appellants-Respondents, McRoberts Protective Agency, Inc., Defendant-Respondent-Appellant, Sonia Meekins, et al., Defendants. _________________________ Wilson Elser Moskowitz Edelman & Dicker LLP, New York (Judy C. Selmeci of counsel), for appellants-respondents. Gallo, Vitucci & Klar, LLP, New York (Chad E. Sjoquist of counsel), for respondent-appellant. Steven J. Horowitz, New York, for respondents. _________________________ Order, Supreme Court, Bronx County (Wilma Guzman, J.), entered on or about August 23, 2012, which, to the extent appealed from as limited by the briefs, denied the motion of defendants Morrisania Towers Housing Company Limited Partnership and NHPMN Management, LLC, for summary judgment dismissing the complaint as against them, and denied defendant McRoberts Protective Agency, Inc.’s motion for summary judgment dismissing the cross claims against it, unanimously reversed, on the law, without costs, and the motions granted. The Clerk is directed to enter judgment accordingly. Defendant Morrisania Towers Housing Company Limited Partnership owns the residential apartment building located at 280/300 East 161st Street in the Bronx, and defendant NHPMN Management, LLC manages the building. Defendant McRoberts Protective Agency, Inc. provides security services for the premises pursuant to an agreement with Morrisania and NHPMN. Plaintiffs, Raymond Carreras and Yolanda Lopez, Carreras’s mother, reside in the building. Although several witnesses described the fight that led to the shooting of Carreras, we will assume for purposes of this motion that Carreras’s own version, as related during his deposition, is true. -

09/28/04 in the Matter of CAMBRIDGE LEASING CORPORATION TAT(H)

CAMBRIDGE LEASING CORPORATION - DETERMINATION - 09/28/04 In the Matter of CAMBRIDGE LEASING CORPORATION TAT(H) 03-11(RP) - DETERMINATION NEW YORK CITY TAX APPEALS TRIBUNAL ADMINISTRATIVE LAW JUDGE DIVISION REAL PROPERTY TRANSFER TAX – THE SALE OF MULTIPLE INDIVIDUAL RESIDENTIAL CONDOMINIUM UNITS ARE SUBJECT TO THE LOWER TAX RATE ACCORDED THE SALE OF CERTAIN RESIDENTIAL PROPERTIES. EVEN IF SUCH SALES ARE SUBJECT TO THE HIGHER TAX RATE, THE SALE OF TW O COMBINED RESIDENTIAL CONDOMINIUM UNITS AND A NON-CONTIGUOUS MAID'S ROOM CONSTITUED THE SALE OF A SINGLE RESIDENCE AND NOT A "BULK SALE" AS DESCRIBED IN FINANCE MEMORANDUM 00-6. SEPTEMBER 28, 2004 NEW YORK CITY TAX APPEALS TRIBUNAL ADMINISTRATIVE LAW JUDGE DIVISION : In the Matter of the Petition : : DETERMINATION of : : TAT(H) 03-11(RP) CAMBRIDGE LEASING CORPORATION : : Gombinski, C.A.L.J.: Petitioner, Cambridge Leasing Corporation, filed a petition for hearing dated May 23, 2003 (the “Petition”) with the New York City (“City”) Tax Appeals Tribunal requesting a redetermination of a deficiency of City Real Property Transfer Tax (“RPTT”) under Chapter 21 of Title 11 of the City Administrative Code (“Code”) in connection with the transfer on January 19, 2000 of real property located at 500 Park Avenue, New York, New York. The parties consented, pursuant to 20 RCNY §1-09(f) of the Tribunal’s Rules of Practice and Procedure, to have the controversy determined on submission without a hearing. The parties submitted a stipulation of facts dated April 1, 2004 with accompanying exhibits. Each party thereafter submitted a brief and a reply brief. The final brief was received on July 27, 2004. -

Constraints of History a Matter of Four Inches in a Landmarked District Hot Financing

TEACHABLE MOMENTS SERVING NEW YORK BOARD MEMBERS & PROPERTY MANAGERS OF CO-OPS & CONDOS ® WWW.HABITATMAG.COM JULY/AUGUST 2013 $3.95 CONSTRAINTS OF HISTORY A Matter of Four Inches in a Landmarked District Hot Financing. financing for all seasons from ncb’s cooperative housing leaders Mayflower Owners Corp. Queens, NY $5,000,000 First Mortgage $500,000 Line of Credit Coral Gardens Owners Corp. Flushing, NY $2,400,000 First Mortgage 380 Riverside Tenants Corp. New York, NY $6,000,000 First Mortgage $1,000,000 Line of Credit 345 Montgomery Owners Corp. Brooklyn, NY $2,000,000 First Mortgage $500,000 Line of Credit Two East End Avenue Apartment Corp. New York, NY $4,000,000 First Mortgage The Townsend House Corp. New York, NY $2,000,000 Line of Credit NCB – The Bank For Your Cooperative Work with the best to be the best. Whether your borrowing need is $350,000 or $50 million, turn to the financial industry leaders at NCB. www.ncb.coop As the premier bank to housing cooperatives and condos in the New York City area, NCB provides experience, expertise and banking solutions to exceed all your expectations. Products Include: First Mortgages | Second Mortgages | Cooperative Unit Mortgages Deposit Products | Lockbox and Payment Processing | Superintendent Units Call the NCB New York team – Sheldon, Ed or Mindy – at (212) 808-0880 for exceptional financial services every season of the year. The NCB Financial Group consists of the National Consumer Cooperative Bank (NCCB) and NCB, FSB, a federally insured savings bank wholly owned by NCCB. Banking and financial services provided by NCB, FSB. -

Bethune West Associates, Offering Plan for Superior

THIS PLAN HAS BEEN AMENDED. SEE INSIDE COVER. WEST VlLLAGE SUPERIOR INK CONDOMINIUM OFFERING PLAN FOR SUPERIOR INK CONDOMINIUMS AND TOWNHOUSES 400 West 12th Street, New York, New York 10014 TOTAL. INITIAL PURCHASE PRICE OF THE 74 RESIDENTIAL UNITS $446,655,000 OFFERED FOR SALE HEREBY: TOTAL INITIAL PURCHASE PRICE OF THE 28 RESIDENT STORAGE ROOM $2,695,000 LICENSES OFFERED FOR SALE HEREBY: AGGREGATE OFFERING PRICE: $449,350,000 (The Condominium has 75 Residential Units, 1 Commercial Unit and 28 Resident Storage Room Licenses. One of the Residential Units, anticipated to be Unit 3L, will be leased to the Condominium Board for use as the Resident Manager's Unit. The Commercial Unit is not being offered for sale hereunder at this time.) Sponsor: Selling Agent: Bethune West Associates, L.L.C. Related Sales LLC 60 Columbus Circle 60 Columbus Circle New York, New York 10023 New York, New York 10023 (212)421-5333 Date of Acceptance for Filing: October 19, 2007 This offering plan may not be used for more than one year from the date of acceptance unless amended- SEE PAGE (Vl) FOR SPECIAL RISKS TO PURCHASERS. PURCHASERS FOR THEIR OWN OCCUPANCY MAY NEVER GAIN CONTROL OF THE CONDOMINIUM BOARD OF MANAGERS UNDER THE TERMS OF THIS PLAN. (SEE SPECIAL RISKS SECTION OF THE PL\N.) BECAUSE THE SPONSOR IS RETAINING THE UNCONDITIONAL RIGHT TO RENT RATHER THAN SELL UNITS, THIS PLAN MAY NOT RESULT IN THE CREATION OF A CONDOMINIUM IN WHICH A MAJORITY OF THE UNITS ARE OWNED BY OWNER-OCCUPANTS OR INVESTORS UNREIATED TO THE SPONSOR.