Ncaoc241.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Struggle to Redevelop a Jim Crow State, 1960–2000

Educating for a New Economy: The Struggle to Redevelop a Jim Crow State, 1960–2000 by William D. Goldsmith Department of History Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Nancy MacLean, Supervisor ___________________________ Edward J. Balleisen ___________________________ Adriane Lentz-Smith ___________________________ Gary Gereffi ___________________________ Helen Ladd Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History in The Graduate School of Duke University 2018 ABSTRACT Educating for a New Economy: The Struggle to Redevelop a Jim Crow State, 1960–2000 by William D. Goldsmith Department of History Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Nancy MacLean, Supervisor ___________________________ Edward J. Balleisen ___________________________ Adriane Lentz-Smith ___________________________ Gary Gereffi ___________________________ Helen Ladd An abstract of a dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History in the Graduate School of Duke University 2018 Copyright by William D. Goldsmith 2018 Abstract This dissertation shows how an array of policymakers, invested in uprooting an unequal political economy descended from the plantation system and Jim Crow, gravitated to education as a centerpiece of development strategy, and why so many are still disappointed in its outcomes. By looking at state-wide policymaking in North Carolina and policy effects in the state’s black belt counties, this study shows why the civil rights movement was vital for shifting state policy in former Jim Crow states towards greater investment in human resources. By breaking down employment barriers to African Americans and opening up the South to new people and ideas, the civil rights movement fostered a new climate for economic policymaking, and a new ecosystem of organizations flourished to promote equitable growth. -

Lessons on Political Speech, Academic Freedom, and University Governance from the New North Carolina

LESSONS ON POLITICAL SPEECH, ACADEMIC FREEDOM, AND UNIVERSITY GOVERNANCE FROM THE NEW NORTH CAROLINA * Gene Nichol Things don’t always turn out the way we anticipate. Almost two decades ago, I came to the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (UNC) after a long stint as dean of the law school in Boulder, Colorado. I was enthusiastic about UNC for two reasons. First, I’m a southerner by blood, culture, and temperament. And, for a lot of us, the state of North Carolina had long been regarded as a leading edge, perhaps the leading edge, of progressivism in the American South. To be sure, Carolina’s progressive habits were often timid and halting, and usually exceedingly modest.1 Still, the Tar Heel State was decidedly not to be confused with Mississippi, Alabama, South Carolina, or my home country, Texas. Frank Porter Graham, Terry Sanford, Bill Friday, Ella Baker, and Julius Chambers had cast a long and ennobling shadow. Second, I have a thing for the University of North Carolina itself. Quite intentionally, I’ve spent my entire academic career–as student, professor, dean, and president–at public universities. I have nothing against the privates. But it has always seemed to me that the crucial democratizing aspirations of higher education in the United States are played out, almost fully, in our great and often ambitious state institutions. And though they have their challenges, the mission of public higher education is a near-perfect one: to bring the illumination and opportunity offered by the lamp of learning to all. Black and white, male and female, rich and poor, rural and urban, high and low, newly arrived and ancient pedigreed–all can, the theory goes, deploy education’s prospects to make the promises of egalitarian democracy real. -

The Judicial Branch North Carolina’S Court System Had Many Levels Before the Judicial Branch Underwent Comprehensive Reorganization in the Late 1960S

The Judicial Branch North Carolina’s court system had many levels before the judicial branch underwent comprehensive reorganization in the late 1960s. Statewide, the N.C. Supreme Court had appellate jurisdiction, while the Superior Court had general trial jurisdiction. Hundreds of Recorder’s Courts, Domestic Relations Courts, Mayor’s Courts, County Courts and Justice of the Peace Courts created by the General Assembly existed at the local level, almost every one individually structured to meet the specific needs of the towns and counties they served. Some of these local courts stayed in session on a nearly full-time basis; others convened for only an hour or two a week. Full-time judges presided over a handful of the local courts, although most were not full-time. Some local courts had judges who had been trained as lawyers. Many, however, made do with lay judges who spent most of their time working in other careers. Salaries for judges and the overall administrative costs varied from court to court, sometimes differing even within the same county. In some instances, such as justices of the peace, court officials were compensated by the fees they exacted and they provided their own facilities. As early as 1955, certain citizens recognized the need for professionalizing and streamlining the court system in North Carolina. At the suggestion of Governor Luther Hodges and Chief Justice M.V. Barnhill, the North Carolina Bar Association sponsored an in-depth study that ultimately resulted in the restructuring of the court system. Implementing the new structure, however, required amending Article IV of the State Constitution. -

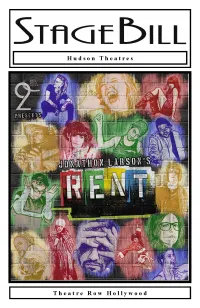

RENT Program

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ Remember the first time you were inspired by a performance? The first time that your eyes opened just a little bit wider to try to capture and record everything you were seeing? Maybe it was your first Broadway show, or the first film that really grabbed you. Maybe it was as simple as a third-grade performance. It’s hard to forget that initial sense of wonder and sudden realization that the world might just contain magic . This is the sort of experience the 2Cents Theatre Group is trying to create. Classic performances are hard to define, but easy to spot. Our Goal is to pay homage and respect to the classics, while simultaneously adding our own unique 2 Cents to create a free-standing performance piece that will bemuse, inform, and inspire. 2¢ Theatre Group is in residence at the Hudson Theatre, at 6539 Santa Monica Boulevard. You can catch various talented members of the 2 Cent Crew in our Monthly Cabaret at the Hudson Theatre Café . the second Sunday of each Month. also from 2Cents AT THE HUDSON… TICKETS ON SALE NOW! May 30 - June 30 EACH WEEK FEATURING LIVE PRE-SHOW MUSIC BY: Thurs 5/30 - Stage 11 Sun 6/2 - Anderson William Thurs 6/6 - 30 North SuN 6/9 - Kelli Debbs Thurs 6/13 - TBD Sun 6/16 - Lee Wahlert Thurs 6/20 - TBD Sun 6/23 - TBD Thurs 6/27 - Fire Chief Charlie Sun 6/30 - Chris Duquee Cody Lyman Kristen Boulé & 2Cents Theatre Board of Directors with Michael Abramson at the Hudson Theatres present Book, Music & Lyrics by Jonathan Larson Dedrick Bonner Kate Bowman Amber Bracken Ariel Jean Brooker Brian -

When African-Americans Were Republicans in North Carolina, the Target of Suppressive Laws Was Black Republicans. Now That They

When African-Americans Were Republicans in North Carolina, The Target of Suppressive Laws Was Black Republicans. Now That They Are Democrats, The Target Is Black Democrats. The Constant Is Race. A Report for League of Women Voters v. North Carolina By J. Morgan Kousser Table of Contents Section Title Page Number I. Aims and Methods 3 II. Abstract of Findings 3 III. Credentials 6 IV. A Short History of Racial Discrimination in North Carolina Politics A. The First Disfranchisement 8 B. Election Laws and White Supremacy in the Post-Civil War South 8 C. The Legacy of White Political Supremacy Hung on Longer in North Carolina than in Other States of the “Rim South” 13 V. Democratizing North Carolina Election Law and Increasing Turnout, 1995-2009 A. What Provoked H.B. 589? The Effects of Changes in Election Laws Before 2010 17 B. The Intent and Effect of Election Laws Must Be Judged by their Context 1. The First Early Voting Bill, 1993 23 2. No-Excuse Absentee Voting, 1995-97 24 3. Early Voting Launched, 1999-2001 25 4. An Instructive Incident and Out-of-Precinct Voting, 2005 27 5. A Fair and Open Process: Same-Day Registration, 2007 30 6. Bipartisan Consensus on 16-17-Year-Old-Preregistration, 2009 33 VI. Voter ID and the Restriction of Early Voting: The Preview, 2011 A. Constraints 34 B. In the Wings 34 C. Center Stage: Voter ID 35 VII. H.B. 589 Before and After Shelby County A. Process Reveals Intention 37 B. Facts 1. The Extent of Fraud 39 2. -

Kennedy Center Education Department. Funding Also Play, the Booklet Presents a Description of the Prinipal Characters Mormons

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 381 835 CS 508 902 AUTHOR Carr, John C. TITLE "Angels in America Part 1: Millennium Approaches." Spotlight on Theater Notes. INSTITUTION John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts, Washington, D.C. SPONS AGENCY Department of Education, Washington, DC. PUB DATE [95) NOTE 17p.; Produced by the Performance Plus Program, Kennedy Center Education Department. Funding also provided by the Kennedy Center Corporate Fund. For other guides in this series, see CS 508 903-906. PUB TYPE Guides General (050) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC01 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Acquired Immune Defi-:ency Syndrome; Acting; *Cultural Enrichment; *Drama; Higher Education; Homophobia; Homosexuality; Interviews; Playwriting; Popular Culture; Program Descriptions; Secondary Education; United States History IDENTIFIERS American Myths; *Angels in America ABSTRACT This booklet presents a variety of materials concerning the first part of Tony Kushner's play "Angels in America: A Gay Fantasia on National Themes." After a briefintroduction to the play, the booklet presents a description of the prinipal characters in the play, a profile of the playwright, information on funding of the play, an interview with the playwright, descriptions of some of the motifs in the play (including AIDS, Angels, Roy Cohn, and Mormons), a quiz about plays, biographical information on actors and designers, and a 10-item list of additional readings. (RS) Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original document. ****):***:%****************************************************)%*****)%* -

State Parks and Development of the Raleigh

“GREEN MEANS GREEN, NOT ASPHALT-GRAY”: STATE PARKS AND DEVELOPMENT OF THE RALEIGH METROPOLITAN AREA, 1936-2016 By GREGORY L. POWELL Bachelor of Arts in History Virginia Polytechnic Institute Blacksburg, Virginia 2002 Master of Arts in History Northern Arizona University Flagstaff, Arizona 2007 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College of the Oklahoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May, 2017 “GREEN MEANS GREEN, NOT ASPHALT-GRAY”: STATE PARKS AND DEVELOPMENT OF THE RALEIGH METROPOLITAN AREA, 1936-2016 Dissertation Approved: Dr. William S. Bryans ________________________________________________ Dissertation Adviser Dr. Michael F. Logan ________________________________________________ Dr. John Kinder ________________________________________________ Dr. Tom Wikle ________________________________________________ ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I was fortunate to receive much valuable assistance throughout the process of researching, writing, and editing this dissertation and would like to extend my appreciation to the following people. My family has been unbelievably patient over the years and I want to thank my wife, Heather, and parents, Arthur and Joy, for their unwavering support. I would also like to thank my children, Vincent and Rosalee, for providing the inspiration for the final push, though they may not understand that yet. The research benefitted from the knowledge and suggestions of archivists, librarians, and staff of several institutions. The folks at the Louis Round Wilson Library at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, particularly those working in the Southern Historical Collection and North Carolina Collection, the David M. Rubenstein Rare Book and Manuscript Library at Duke University, and the Z. Smith Reynolds Library at Wake Forest University, and the North Carolina State Archives deserve praise for their professionalism assistance. -

General Information

FEDERAL ELECTED OFFICIALS U.S. SENATE TERM 6 YEARS Kay R. Hagan (D) Term ends 2014 521 Dirksen Senate Office Bldg. Washington, DC 20510 1-877-852-9462 fax (202) 228-2563 [email protected] 310 New Bern Ave. Raleigh, NC 27601 (919)-856-4630 Richard Burr (R) Terms ends 2016 217 Russell Senate Office Building Washington, DC 20510 (202)-224-3154 fax (202) 228-2981 2000 W First Street, Suite 508 Winston Salem, NC 27104 800-685-8916 (toll free) fax (336) 725-4493 U.S. CONGRESS TERM 2 YEARS (6th District) Howard Coble (R) Term ends 2014 2188 Rayburn House Office Building Washington, DC 20515-3306 (202) 225-3065 Fax: (202) 225-8611 2102 North Elm Street, Suite B Greensboro, NC 27408-5100 (336) 333-5005 Fax: (336) 333-5048 STATE OFFICES 4 yr. Terms end 2016 GOVERNOR Pat McCrory (R) Office of the Governor 20301 Mail Service Center Raleigh, NC 27699-0301 (919) 733-4240 fax (919) 733-2120 800-662-7952 (toll free) LIEUTENANT GOVERNOR Dan Forest (R) 20401 Mail Service Center Raleigh, NC 27699-0401 (919) 733-7350 fax (919) 733-6595 SECRETARY OF STATE Elaine F. Marshall (D) P O Box 29622 Raleigh, NC 27626-0622 (919) 807-2005 fax (919) 807-2020 STATE AUDITOR Beth A. Wood (D) 20601 Mail Service Center Raleigh, NC 27699-0401 (919) 807-7500 fax (919) 807-7647 STATE TREASURER Janet Cowell (D) 325 N. Salisbury Street Raleigh, N.C. 27603 (919) 508-5176 fax (919) 508-5167 SUPT. OF PUBLIC INSTRUCTION June St. Clair Atkinson (D) 301 N. -

DIGITAL PLAYBILL MARCH 2021 BLUEBARN | 32 | Season of the Unknown

BY JORDAN HARRISON DIGITAL PLAYBILL MARCH 2021 BLUEBARN | 32 | Season of the Unknown eason 32 marks a profound shift in perspective. This year we give focus to Sbuilding on BLUEBARN’s transformative programming and services, seeding the fires that will light our way for years to come. A different kind of season awaits us. A different kind of membership awaits you… In these extraordinary times, we invite you to become caretakers of BLUEBARN’s mission. We invite you to provoke thought, emotion, action, and change in our community. Your BLUEBARN membership is a commitment, not to a certain number of productions or nights of theatre, but to the BLUEBARN’s essential work on and off the stage, our values, our art, and our artists. Incomparable theatre and incandescent storytelling remain at the core of our work. For these wild times, we have imagined adventurous new ways to bring the power of story back into all our lives. We have also dreamed up better ways to harness your BLUEBARN membership to “The future is in disorder. extend the reach of our art and sustain A door like this the lives of artists. has cracked open BLUEBARN is proud to announce a host five or six times since we got up of programs and programming that we on our hind legs. It hope will ignite and inspire you. We is the best possible must acknowledge as we do so the very time to be alive, when real uncertainty of the coming year. almost everything you Our season accepts disruptions and thought you knew was adaptations to shifting circumstances as wrong.” givens. -

Whichard, Willis P

914 PORTRAIT CEREMONY OF JUSTICE WHICHARD OPENING REMARKS and RECOGNITION OF JAMES R. SILKENAT by CHIEF JUSTICE SARAH PARKER The Chief Justice welcomed the guests with the following remarks: Good morning, Ladies and Gentlemen. I am pleased to welcome each of you to your Supreme Court on this very special occasion in which we honor the service on this Court of Associate Justice Willis P. Whichard. The presentation of portraits has a long tradition at the Court, beginning 126 years ago. The first portrait to be presented was that of Chief Justice Thomas Ruffin on March 5, 1888. Today the Court takes great pride in continuing this tradition into the 21st century. For those of you who are not familiar with the Court, the portraits in the courtroom are those of former Chief Justices, and those in the hall here on the third floor are of former Associate Justices. The presentation of Justice Whichard’s portrait today will make a significant contribution to our portrait collection. This addition allows us not only to appropriately remember an important part of our history but also to honor the service of a valued member of our Court family. We are pleased to welcome Justice Whichard and his wife Leona, daughter Jennifer and her husband Steve Ritz, and daughter Ida and her husband David Silkenat. We also are pleased to welcome grand- children Georgia, Evelyn, and Cordia Ritz; Chamberlain, Dawson, and Thessaly Silkenat; and Ida’s in-laws Elizabeth and James Silkenat. Today we honor a man who has distinguished himself not only as a jurist on this Court and the Court of Appeals, but also as a lawyer legislator serving in both Chambers of the General Assembly, as Dean of the Campbell Law School, and as a scholar. -

Three Tall Women: Director’S Notes Four Fortunate Women (And One Man)

PRODUCTION SUPPORT IS GENEROUSLY PROVIDED BY SYLVIA D. CHROMINSKA, DR. DESTA LEAVINE IN MEMORY OF PAULINE LEAVINE, SYLVIA SOYKA, THE WESTAWAY CHARITABLE FOUNDATION AND BY JACK WHITESIDE LAND ACKNOWLEDGEMENT Welcome to the Stratford Festival. It is a great privilege to gather and share stories on this beautiful territory, which has been the site of human activity — and therefore storytelling — for many thousands of years. We wish to honour the ancestral guardians of this land and its waterways: the Anishinaabe, the Haudenosaunee Confederacy, the Wendat, and the Attiwonderonk. Today many Indigenous peoples continue to call this land home and act as its stewards, and this responsibility extends to all peoples, to share and care for this land for generations to come. A MESSAGE FROM OUR ARTISTIC DIRECTOR WORLDS WITHOUT WALLS Two young people are in love. They’re next- cocoon, and now it’s time to emerge in a door neighbours, but their families don’t get blaze of new colour, with lively, searching on. So they’re not allowed to meet: all they work that deals with profound questions and can do is whisper sweet nothings to each prompts us to think and see in new ways. other through a small gap in the garden wall between them. Eventually, they plan to While I do intend to program in future run off together – but on the night of their seasons all the plays we’d planned to elopement, a terrible accident of fate impels present in 2020, I also know we can’t just them both to take their own lives. -

T a T U M B E

T A T U M B E C K P H O N E : (614) 623-9613 | E M A I L : [email protected] H A I R : Brown | E Y E S : Green | H E I G H T : 5’6” P r o f e s s i o n a l T h e a t r e Otterbein Summer Theatre Guys and Dolls Sarah Brown Lenny Leibowitz Snoopy!!! Lucy Melissa Lusher E d u c a t i o n a l T h e a t r e Otterbein University Chicago Velma Kelly Melissa Lusher Singin’ in the Rain Lina Lamont Christina Kirk The Diary of Anne Frank Anne Frank Mark Mineart Damn Yankees Lola u/s/Ensemble Mark Mineart Big Fish Witch/Josephine u/s/Ensemble Thom Christopher Warren Dance Concert 2017: Move Me Featured Dancer/Ensemble Stella Kane E d u c a t i o n / T r a i n i n g BFA Musical Theatre, Otterbein University (2020) Acting Melissa Lusher, Thom Christopher Warren, Mark Mineart, Lenny Leibowitz, Christina Kirk Dance Jazz, Hip Hop, Modern, Ballet, Tap Stella Kane, Anna Elliott, Emily Glinski, Christeen Stridsberg, Scott Brown Voice Dr. Keyona Willis, Michael Hamilton Speech Melissa Lusher Masterclasses Andrew Lippa, Dick Scanlan, Randy Skinner, Cory Michael Smith, Mathew Edwards, Lili Froehlich, Lindsay Nicole Chambers, Jim Cooney S p e c i a l S k i l l s Piano (8 years), basic accordion, ZFX Flight Trained, improvisational comedy/musical comedy, Dialects (RP, Irish, Spanish, Southern/Deep South) KYLE BRACE Voice: Baritone (E2-G4) | Hair: Black | Eyes: Brown | Height: 6’1 [email protected] | 814-790-2439 | www.kylebrace.com PROFESSIONAL THEATRE OTTERBEIN SUMMER THEATRE Oklahoma Jud Fry Lenny Leibowitz Snoopy Charlie Brown Melissa Lusher SHENANDOAH SUMMER MUSIC THEATRE Ragtime Ensemble Jeremy Scott Blaustein Young Frankenstein Ensemble Edward Carignan WEATHERVANE PLAYHOUSE Meet Me in St.