Understanding Livelihood Characteristics and Vulnerabilities of Small- Scale Fishers in Coastal Bangladesh Atiqur Rahman Sunny1,2*, Shamsul Haque Prodhan1, Md

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Effect of Climate and Anthropogenic Change on the Spatial Variability of Turbidity Maxima in the Southwest Delta of Bangladesh

The effect of climate and anthropogenic change on the spatial variability of turbidity maxima in the southwest delta of Bangladesh. by MORSHEDA BEGUM Erasmus Mundus Joint Master in Water and Coastal Management. WACOMA 9/28/2018 Research Supervisor Dr Alfredo Iquierdo González Research Co-Supervisor Dr. Hans Middelkoop Mentors: Mohammed Feroz Islam The author has been financially supported by Erasmus Mundus This Master Thesis was carried out in the Department of Applied Physics, Faculty of Marine and Environmental Sciences University of Cadiz, as part of the UNESCO/UNITWIN/WiCoP activities in Cádiz, Spain, and in Utrecht University. The work was part of the project “Living polders: dynamic polder management for sustainable livelihoods, applied to Bangladesh” financed by The Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (NOW) (W 07.69.201). The author was supported by an ERASMUS MUNDUS scholarship. STATEMENT I hear by declare that this work has been carried out by me and the thesis has been composed by me and has not been submitted for any other degree or professional qualification. This work is presented to obtain a masters’ degree in Water and Coastal Management (WACOMA). ----------------------------- MORSHEDA BEGUM D. Alfredo Izquierdo González, Profesor del Departamento de Fizică Aplicată de la Universidad de Cádiz y D. Hans Middelkoop, Profesor del Departamento de Departamento de Geografía Física de la Universidad de Utrecht, como sus directores HACEN CONSTAR: Que esta Memoria, titulada “(El efecto del cambio climático y antropogénico sobre la variabilidad espacial de los máximos de turbidez en el delta sudoeste de Bangladesh)”, presentada por D. Morsheda Begum, resume su trabajo de Tesis de Master y, considerando que reúne todos los requisitos legales, autorizan su presentación y defensa para optar al grado de Master Erasmus Mundus in Water and Coastal Management (WACOMA). -

Cricket World Cup Begins Mar 8 Schedule on Page-3

www.Asia Times.US NRI Global Edition Email: [email protected] March 2016 Vol 7, Issue 3 Cricket World Cup begins Mar 8 Schedule on page-3 Indian Team: Pakistan Team: Shahid Afridi (c), Anwar Ali, Ahmed Shehzad MS Dhoni (capt, wk), Shikhar Dhawan, Rohit Mohammad Hafeez Bangladesh Team: Sharma, Virat Kohli, Ajinkya Rahane, Yuvraj Shoaib Malik, Mohammad Irfan Squad: Tamim Iqbal, Soumya Sarkar, Moham- Singh, Suresh Raina, R Ashwin, Ravindra Jadeja, Sharjeel Khan, Wahab Riaz mad Mithun, Shakib Al Hasan, Mushfiqur Ra- Mohammed Shami, Harbhajan Singh, Jasprit Mohammad Nawaz, Muhammad Sami him, Sabbir Rahman, Mashrafe Mortaza (capt), Bumrah, Pawan Negi, Ashish Nehra, Hardik Khalid Latif, Mohammad Amir Mahmudullah Riyad, Nasir Hossain, Nurul Pandya. Umar Akmal, Sarfraz Ahmed, Imad Wasim Hasan, Arafat Sunny, Mustafizur Rahman, Al- Amin Hossain, Taskin Ahmed and Abu Hider. Australia Team: Steven Smith (c), David Warner (vc), Ashton Agar, Nathan Coulter-Nile, James Faulkner, Aaron Finch, John Hastings, Josh Hazlewood, Usman Khawaja, Mitchell Marsh, Glenn Max- well, Peter Nevill (wk), Andrew Tye, Shane Watson, Adam Zampa England: Eoin Morgan (c), Alex Hales, Ja- Asia Times is Globalizing son Roy, Joe Root, Jos Buttler, James Vince, Ben Now appointing Stokes, Moeen Ali, Chris Jordan, Adil Rashid, David Willey, Steven Finn, Reece Topley, Sam Bureau Chiefs to represent Billings, Liam Dawson New Zealand Team: Asia Times in ALL cities Kane Williamson (c), Corey Anderson, Trent Worldwide Boult, Grant Elliott, Martin Guptill, Mitchell McClenaghan, -

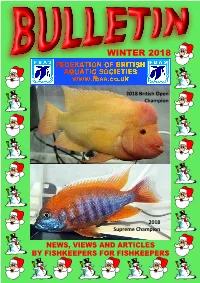

2018 Diamond Class Final

WINTER 2018 2018 British Open Champion COVER PHOTO 2018 Les Pearce Supreme Champion NEWS, VIEWS AND ARTICLES BY FISHKEEPERS FOR FISHKEEPERS Page 1 QUARTERLY BULLETIN WINTER 2018 EDITORIAL Page 3 BEE KEEPING Tom & Pat Bridges Page 4 KNOW YOUR FISH (Thayeria boehlkei) Dr David Pool Page 8 MARINE FILTRATION SYSTEM ON A ROLL & SHRIMPS IN A SPIN! Page 11 VICTOR’S FISH ROOM Jonathan Theuma Carabez Page 14 HABITAT & AQUARIA F F Schmidt Page 18 THE LAST FESTIVAL OF FISHKEEPING RESULTS AND NEWS Page 29 Opinions expressed in any article remain those of the author and are not necessarily endorsed by this publication. All material is the copyright of the author, the photographer and/or the FBAS and should be treated as such. Edited, published and produced for the FBAS website by Les Pearce Page 2 EDITORIAL Welcome to the Winter 2018 edition of the Bulletin. There are some outstanding items inside - something of interest for everybody. There is a fascinating article on Habitat and Aquaria and an in-depth look at how they do it in Malta as we are invited in to the fish room of Mr Victor Grech, a long-serving and valued member of Malta Aquarists’ Society. There is also an interesting article on Bumblebee Gobies plus all the news and results from the final Festival of Fishkeeping at Hounslow Urban Farm. Please, please keep the articles and information coming in. Anything that you think may be of interest to fellow fishkeepers is always welcome. You can contact me or send articles using the details below. -

A Checklist of Fishes and Fisheries of the Padda (Padma) River Near Rajshahi City

Available online at www.ijpab.com Farjana Habib et al Int. J. Pure App. Biosci. 4 (2): 53-57 (2016) ISSN: 2320 – 7051 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.18782/2320-7051.2248 ISSN: 2320 – 7051 Int. J. Pure App. Biosci. 4 (2): 53-57 (2016) Research Article A checklist of Fishes and Fisheries of the Padda (Padma) River near Rajshahi City Farjana Habib 1*, Shahrima Tasnin 1 and N.I.M. Abdus Salam Bhuiyan 2 1Research Scholar, 2Professor Department of Zoology, University of Rajshahi, Bangladesh *Corresponding Author E-mail: [email protected] Received: 22.03.2016 | Revised: 30.03.2016 | Accepted: 5.04.2016 ABSTRACT The present study was carried out to explore the existing fish fauna of the Padda (Padma) River near Rajshahi City Corporation area for a period of seven months (February to August). This study includes a checklist of the species composition found to inhabit the waters of this region, which included 82 species of fishes under 11 orders and two classes. The list also includes two species of prawns. A total of twenty nine fish species of the study area are recorded as threatened according to IUCN red list. This finding will help to evaluate the present status of fishes in Padda River and their seasonal abundance. Key words : Exotic, Endangered, Rajshahi City, Padda (Padma) River INTRODUCTION Padda is one of the main rivers of Bangladesh. It Kilometers (1,400 mi) from the source, the is the main distributary of the Ganges, flowing Padma is joined by the Jamuna generally southeast for 120 kilometers (75 mi) to (Lower Brahmaputra) and the resulting its confluence with the Meghna River near combination flows with the name Padma further the Bay of Bengal 1. -

January 13, 2015 London Aquaria Society Tommy Lam from Shrimp Fever Will Be Coming to Do a Presentation for Us

Volume 59, Issue 1 January 13, 2015 London Aquaria Society www.londonaquariasociety.com Tommy Lam from Shrimp Fever will be coming to do a presentation for us. Golden and Dwarf (Nannostomus beckfordi) and that can fit into it. For my pets, Pencilfish Profile dwarf pencilfish (Nannostomus I usually offer them occasional marginatus). Generally they are feed of brine shrimps and I add www.allabout-aquariumfish.com rather shy and would some- the finely crushed food flakes Guest post contributed by Mark Edgar (California) times become motionless, swim- that are specially made for tiny ming at the same spot. The tank fish. Sometimes I even took the Pencilfish is a tiny and that houses the fish should be a effort to introduce a variety of peaceful community fish charac- well-planted aquarium with at foods to enrich their diet such terized by its thin body which is least 50 percent of overall area as growing live daphnia or col- made up of three different color covered with dense vegetation lect these from ponds coupled stripes. There are quite a num- to provide a good hiding spot. I together with mosquito larva if ber of different species that even took the effort to add I happen to bump across these form the pencilfish family group some small empty clay pots so as well. What I notice is that of fish and each has its own dif- that the fish feels more like at my pencilfish simply love these ferent appearances depending home for them. Pencilfish prefer until I find myself unable to on the location on which they to move in groups and if possi- find constant food supply to were caught. -

Fish Composition in Dong Nai Biosphere Reserve in Vietnam

30 Nong Lam University, Ho Chi Minh City Fish composition in Dong Nai biosphere reserve in Vietnam Tam T. Nguyen∗, Loi N. Nguyen, Bao Q. Lam, Tru C. Huynh, Dang H. Nguyen, Nam B. Nguyen, Tien D. Mai, & Thuong P. Nguyen Faculty of Fisheries, Nong Lam University, Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Research Paper Dong Nai biosphere reserve (DNBR) is well known for its high level of biodiversity and of global meaningful ecosystem. The fauna includes Received: September 03, 2019 84 species of mammals belonging to 28 families, 10 orders; 407 bird Revised: October 07, 2019 species; 141 reptile and amphibian species; 175 fish species; 2,017 Accepted: November 21, 2019 insect species. The fish fauna of DNBR maintains many rare and endangered fish species recorded in the Vietnam red book and inter- national union for conservation of nature red list (IUCN's red list) Keywords such as Scleropages formosus and many other rare fish species, such as Morulius chrysophekadion, Chitala ornata, Probarbus jullieni, Cy- clocheilichthys enoplos. This study was aimed to identify fish com- Dong Nai biosphere reserve position distributed in DNBR. After the sampling period (01/2019 Endanger to 08/2019), a total of 114 fish species belonging to 11 orders and Fish biodiversity 28 families were recorded in DNBR. There were 09 species of fish on Species compositions the list of rare and endangered fish species of Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development of Vietnam, 3 species (Chitala ornata, Cos- mochilus harmandi and Hemibagus filamentus) on the Vietnam red ∗Corresponding author list book; 01 species (Ompok bimaculatus) on the IUCN's red list, 11 exotic species, 78 commercial species and 13 species having potential Nguyen Thanh Tam as aquarium fish. -

Climate Change and Anthropogenic Interferences for the Morphological Changes of the Padma River in Bangladesh

American Journal of Climate Change, 2021, 10, 167-184 https://www.scirp.org/journal/ajcc ISSN Online: 2167-9509 ISSN Print: 2167-9495 Climate Change and Anthropogenic Interferences for the Morphological Changes of the Padma River in Bangladesh Md. Azharul Islam1*, Md. Sirazum Munir1, Md. Abul Bashar2, Kizar Ahmed Sumon3, Mohammad Kamruzzaman4, Yahia Mahmud5 1Department of Environmental Science, Bangladesh Agricultural University, Mymensingh, Bangladesh 2Bangladesh Fisheries Research Institute, Chandpur, Bangladesh 3Department of Fisheries Management, Faculty of Agriculture, Bangladesh Agricultural University, Mymensingh, Bangladesh 4Senior Scientific Officer, Farm Machinery and Postharvest Technology Division, Bangladesh Rice Research Institute, Gazipur, Bangladesh 5Bangladesh Fisheries Research Institute, Mymensingh, Bangladesh How to cite this paper: Islam, Md. A., Abstract Munir, Md. S., Bashar, Md. A., Sumon, K. A., Kamruzzaman, M., & Mahmud, Y. (2021). This research aims to identify the morphological changes of the Padma River Climate Change and Anthropogenic Inter- due to the effects of anthropogenic climate change. The morphological changes ferences for the Morphological Changes of were measured by aerial satellite images and their historical comparison, ter- the Padma River in Bangladesh. American restrial survey, sedimentation in the riverbed, water flow, water discharge, Journal of Climate Change, 10, 167-184. siltation, and erosion along the river, etc. The Padma River has been analyzed https://doi.org/10.4236/ajcc.2021.102008 over the period from 1971 to 2020 using multi-temporal Landsat images and Received: March 5, 2021 long-term water flow data. The climatic parameters data related to tempera- Accepted: May 11, 2021 ture and rainfall were collected from 21 metrological stations distributed Published: May 14, 2021 throughout Bangladesh over a 50-year period (1965-2015) to evaluate the magnitude of these changes statistically and spatially. -

Ivelihood Status of the Fish Farmers in Some Selected Areas of Tarakanda Upazila of Mymensingh District

J. Agrofor. Environ. 3 (2): 85-89, 2010 ISSN 1995-6983 Livelihood status of the fish farmers in some selected areas of Tarakanda upazila of Mymensingh district H. Ali, M.A.K. Azad1, M. Anisuzzaman, M.M.R. Chowdhury, M. Hoque and M.I. Shariful2 Department of Aquaculture, Bangladesh Agricultural University, Mymensingh, 1Char Livelihood Programme, 2Department of Fisheries Management, Bangladesh Agricultural University, Mymensingh Abstract: This study was conducted using multiple methodological tools including participatory rural appraisal (PRA) tools and mainly questionnaire survey to assess the livelihood status of the fish farmer and socio-economic problems associated with fish farming in some selected areas of Tarakanda upazila of Mymensingh district from October 2008 to march 2009. The average pond size was 0.17 ha with seasonal (33.34%) and perennial ponds (66.66%), while 70% ponds were single and 30% multiple ownership. Most of the fish farmers were belonged to the age category of 31 to 40 years and 45% household had family members 4 to 5, represented 57.5% nuclear and 42.5% joint family. Average education level of 8.2 years schooling, while 85% Muslims and 15% Hindus. About 50% of the households were tinshed and reminder 23%, 23% and 4% were katcha, semi pucca and pucca, respectively. The average annual income of the farmers was estimated at BDT 42,500 and 90% of the farmers used their own money for farming, while 10% received loan. About 62.5% of the farmer’s were used semi-pucca sanitary and 12.5% used pucca while 25% used katcha sanitary. About 90% farmers used own tube- well while 10% used neighbors tube-well and 95% of the farmers had electricity facilities while 5% farmers did not have electricity facilities. -

BANGLADESH Transboundary Rivers

Transboundary Conservation of the mangrove ecosystem of Sundarbans BANGLADESH Laskar Muqsudur Rahman Forest Department, BANGLADESH E-mail: [email protected] Third Workshop on Water and Adaptation to Climate Change in transboundary basins Geneva. Switzerland 25-26 April 2012 Bangladesh - Location & Climate The country is bordered on the west, north, and east by a 4,095-km land frontier with India and, in the southeast, by a short land and water frontier of 193 km with Myanmar. Bangladesh has a tropical monsoon climate - • Maximum summer temperatures 38 - 41°C • Winter day temperature 16–20 °C & at night around 10 °C • Annual rainfall ranges between 1,600 mm and 4,780 mm • Natural calamities - floods, tropical cyclones & tidal surges —ravage the country, particularly the coastal zone, almost every year. Ecosystem in Bangladesh Forests River Wetlands The 4 broad types of ecosystems : Terrestrial forest ecosystems, Inland freshwater ecosystems (Rivers, wetlands) Man-made ecosystems (Homegardens), and Coastal and marine ecosystems (Mangroves) Mangroves Coastal Homegardens Sundarban Mangrove Ecosystem Bangladesh and India shares the largest single tract of estuarine mangrove forests in the world which is globally known as the Sundarbans. The dominant tree species of the Sundarban is Sundari (Heritiera fomes). In Bangla ‘Sundar’ means beautiful. Sundarban is listed as UNESCO World Heritage site in 1997 and Ramsar Wetland Site in 1992. The Sundarbans spans 10,000 sq.km., about 6,000 sq. km. of which is in Bangladesh Sundarban Mangrove Ecosystem With its array of trees and wildlife the forest is a showpiece of natural history. It is a center of economic activities such as extraction of timber, fishing and collection of NTFP (e.g. -

(1) Hydrological and Morphological Data of Padma River the Ganges River Drains the Southern Slope of the Himalayas

The Study on Bheramara Combined Cycle Power Station in Bangladesh Final Report 4.6.5 Water Source (1) Hydrological and morphological data of Padma River The Ganges River drains the southern slope of the Himalayas. After breaking through the Indian shield, the Ganges swings to the east along recent multiple faults between the Rajmahal Hills and the Dinajpur Shield. The river enters Bangladesh at Godagari and is called Padma. Before meeting with the Jamuna, the river travels about 2,600km, draining about 990,400km2 of which about 38,880km2 lies within Bangladesh. The average longitudinal slope of water surface of the Ganges(Padma) River is about 5/100,000. Size of bed materials decreases in the downstream. At the Harding Bridge, the average diameter is about 0.15mm. The river planform is in between meandering and braiding, and varies temporally and spatially. Sweeping of the meandering bends and formation of a braided belt is limited within the active corridor of the river. This corridor is bounded by cohesive materials or man-made constructions that are resistant to erosion. Materials within these boundaries of the active corridor consist of loosely packed sand and silt, and are highly susceptible to erosion. Hydrological and morphological data of Padma River has been corrected by BWDB at Harding Bridge and crossing line of RMG-13 shown in the Figure I-4-6-4. Harding Bridge Origin (x=0) RMG-13 Padma River 3.66km Figure I-4-6-4 Bheramara site and Padma River Figure I-4-6-5 shows the water level at Harding Bridge between 1976 and 2006. -

DINÂMICA EVOLUTIVA DO Dnar EM CROMOSSOMOS DE PEIXES DA FAMÍLIA ELEOTRIDAE E REVISÃO CITOGENÉTICA DA ORDEM GOBIIFORMES(OSTEICHTHYES, TELEOSTEI)

DINÂMICA EVOLUTIVA DO DNAr EM CROMOSSOMOS DE PEIXES DA FAMÍLIA ELEOTRIDAE E REVISÃO CITOGENÉTICA DA ORDEM GOBIIFORMES(OSTEICHTHYES, TELEOSTEI) SIMIÃO ALEFE SOARES DA SILVA ________________________________________________ Dissertação de Mestrado Natal/RN, Fevereiro de 2019 UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DO RIO GRANDE DO NORTE CENTRO DE BIOCIÊNCIAS PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM SISTEMÁTICA E EVOLUÇÃO DINÂMICA EVOLUTIVA DO DNAr EM CROMOSSOMOS DE PEIXES DA FAMÍLIA ELEOTRIDAE E REVISÃO CITOGENÉTICA DA ORDEM GOBIIFORMES (OSTEICHTHYES, TELEOSTEI) Simião Alefe Soares da Silva Dissertação apresentada ao Programa de Pós-Graduação em Sistemática e Evolução da Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte, como parte dos requisitos para obtenção do título de Mestre em Sistemática e Evolução. Orientador: Dr. Wagner Franco Molina Co-Orientador: Dr. Paulo Augusto de Lima Filho Natal/RN 2019 Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte - UFRN Sistema de Bibliotecas - SISBI Catalogação de Publicação na Fonte. UFRN - Biblioteca Central Zila Mamede Silva, Simião Alefe Soares da. Dinâmica evolutiva do DNAr em cromossomos de peixes da família Eleotridae e revisão citogenética da ordem gobiiformes (Osteichthyes, Teleostei) / Simião Alefe Soares da Silva. - 2019. 69 f.: il. Dissertação (mestrado) - Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte, Centro de Biociências, Programa de Pós-Graduação em 1. Evolução cromossômica - Dissertação. 2. Diversificação cariotípica - Dissertação. 3. Rearranjos cromossômicos - Dissertação. 4. DNAr - Dissertação. 5. Microssatélites - Dissertação. I. Lima Filho, Paulo Augusto de. II. Molina, Wagner Franco. III. Título. RN/UF/BCZM CDU 575:597.2/.5 SIMIÃO ALEFE SOARES DA SILVA DINÂMICA EVOLUTIVA DO DNAr EM CROMOSSOMOS DE PEIXES DA FAMÍLIA ELEOTRIDAE E REVISÃO CITOGENÉTICA DA ORDEM GOBIIFORMES (OSTEICHTHYES, TELEOSTEI) Dissertação apresentada ao Programa de Pós-Graduação em Sistemática e Evolução da Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte, como requisitos para obtenção do título de Mestre em Sistemática e Evolução com ênfase em Padrões e Processos Evolutivos. -

Along River Ganga

Impact assessment of coal transportation through barges along the National Waterway No.1 (Sagar to Farakka) along River Ganga Project Report ICAR-CENTRAL INLAND FISHERIES RESEARCH INSTITUTE (INDIAN COUNCIL OF AGRICULTURAL RESEARCH) BARRACKPORE, KOLKATA 700120, WEST BENGAL Impact assessment of coal transportation through barges along the National Waterway No.1 (Sagar to Farakka) along River Ganga Project Report Submitted to Inland Waterways Authority of India (Ministry of Shipping, Govt. of India) A 13, Sector 1, Noida 201301, Uttar Pradesh ICAR – Central Inland Fisheries Research Institute (Indian Council of Agricultural Research) Barrackpore, Kolkata – 700120, West Bengal Study Team Scientists from ICAR-CIFRI, Barrackpore Dr. B. K. Das, Director & Principal Investigator Dr. S. Samanta, Principal Scientist & Nodal Officer Dr. V. R. Suresh, Principal Scientist & Head, REF Division Dr. A. K. Sahoo, Scientist Dr. A. Pandit, Principal Scientist Dr. R. K. Manna, Senior Scientist Dr. Mrs. S. Das Sarkar, Scientist Ms. A. Ekka, Scientist Dr. B. P. Mohanty, Principal Scientist & Head, FREM Division Sri Roshith C. M., Scientist Dr. Rohan Kumar Raman, Scientist Technical personnel from ICAR-CIFRI, Barrackpore Mrs. A. Sengupta, Senior Technical Officer Sri A. Roy Chowdhury, Technical Officer Cover design Sri Sujit Choudhury Response to the Query Points of Expert Appraisal Committee POINT NO. 1. Long term, and a minimum period of one year continuous study shall be conducted on the impacts of varying traffic loads on aquatic flora and fauna with particular reference to species composition of different communities, abundance of selective species of indicator value, species richness and diversity and productivity Answered in page no. 7 – 12 (methodology) and 31 – 71 (results) of the report POINT NO.2.