Human-Animal Relationships

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Human Ecology Review

HUMAN ECOLOGY REVIEW Volume 22, Number 1, 2015 RESEARCH AND THEORY IN HUMAN ECOLOGY Introduction: Progress in Structural Human Ecology 3 Thomas Dietz and Andrew K. Jorgenson Metatheorizing Structural Human Ecology at the Dawn of the Third Millennium 13 Thomas J. Burns and Thomas K. Rudel Animals, Capital and Sustainability 35 Thomas Dietz and Richard York How Does Information Communication Technology Affect Energy Use? 55 Stefano B. Longo and Richard York Environmental Sustainability: The Ecological Footprint in West Africa 73 Sandra T. Marquart-Pyatt Income Inequality and Residential Carbon Emissions in the United States: A Preliminary Analysis 93 Andrew K. Jorgenson, Juliet B. Schor, Xiaorui Huang and Jared Fitzgerald Urbanization, Slums, and the Carbon Intensity of Well-being: Implications for Sustainable Development 107 Jennifer E. Givens Water, Sanitation, and Health in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Cross-national Analysis of Maternal and Neo-natal Mortality 129 Jamie M. Sommer, John M. Shandra, Michael Restivo and Carolyn Coburn Contributors to this Issue 153 Research and Theory in Human Ecology 1 Introduction: Progress in Structural Human Ecology Thomas Dietz1 Environmental Science and Policy Program, Department of Sociology and Animal Studies Program, Michigan State University, East Lansing, United States Andrew K. Jorgenson Department of Sociology, Environmental Studies Program, Boston College, Boston, United States Abstract Structural human ecology is a vibrant area of theoretically grounded research that examines the interplay between structure and agency in human– environment interactions. This special issue consists of papers that highlight recent advances in the tradition. Here, the guest co-editors provide a short background discussion of structural human ecology, and offer brief summaries of the papers included in the collection. -

NATURE, SOCIOLOGY, and the FRANKFURT SCHOOL by Ryan

NATURE, SOCIOLOGY, AND THE FRANKFURT SCHOOL By Ryan Gunderson A DISSERTATION Submitted to Michigan State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Sociology – Doctor of Philosophy 2014 ABSTRACT NATURE, SOCIOLOGY, AND THE FRANKFURT SCHOOL By Ryan Gunderson Through a systematic analysis of the works of Max Horkheimer, Theodor W. Adorno, Herbert Marcuse, and Erich Fromm using historical methods, I document how early critical theory can conceptually and theoretically inform sociological examinations of human-nature relations. Currently, the first-generation Frankfurt School’s work is largely absent from and criticized in environmental sociology. I address this gap in the literature through a series of articles. One line of analysis establishes how the theories of Horkheimer, Adorno, and Marcuse are applicable to central topics and debates in environmental sociology. A second line of analysis examines how the Frankfurt School’s explanatory and normative theories of human- animal relations can inform sociological animal studies. The third line examines the place of nature in Fromm’s social psychology and sociology, focusing on his personality theory’s notion of “biophilia.” Dedicated to 바다. See you soon. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I owe my dissertation committee immense gratitude for offering persistent intellectual and emotional support. Linda Kalof overflows with kindness and her gentle presence continually put my mind at ease. It was an honor to be the mentee of a distinguished scholar foundational to the formation of animal studies. Tom Dietz is the most cheerful person I have ever met and, as the first environmental sociologist to integrate ideas from critical theory with a bottomless knowledge of the environmental social sciences, his insights have been invaluable. -

Environmental Kuznets Curve Hypothesis? Or Pollution Haven Hypothesis? a Comparison of the Two

1 Environmental Kuznets Curve Hypothesis? or Pollution Haven Hypothesis? A Comparison of the Two With the world becoming a global economy and global trade necessary, the concern for environmental quality has increased. There are an increasing amount of empirical studies devoted to the Environmental Kuznets Curve (EKC) theory, to determine the relationship between a country’s income and its pollution levels. The EKC theory basically states that initially as a country’s income increases its pollution increases, but at a certain level of income its pollution levels will start to decrease. The existence of the EKC hypothesis that has been shown through empirical studies raises one main question. Should the evidence supporting the existence of the EKC be used to set policy measures? Or, does it just show a relationship that should have no impact on policy decisions? One explanation for the existence of the EKC is the pollution haven hypothesis. It basically states that when countries start to import more goods the industries they used to produce these goods have moved to other countries taking the pollution created by them to those countries. I will first determine if the EKC hypothesis holds true for CO2 emissions related to income in a cross sectional data set for 156 countries. Second, I will narrow the field to two countries, the U. S. and Mexico, to see if evidence can be found to support the EKC hypothesis. I will use CO2 emissions related to GNP that is matched for each of the countries. Comparing each of the data sets for each of these two countries may offer insight to the pollution haven hypothesis as well. -

Annual Report 2017-2018.Pdf

COLD SPRING HARBOR CENTRAL SCHOOL DISTRICT ANNUAL REPORT 2017-2018 October 9, 2018 Cold Spring Harbor Central School District The 2017-2018 school year was one in which we created a variety of new learning experiences for our students, all behind the efforts of Cold Spring Harbor teachers and leaders to prepare them for the future. Following the vision driving the district’s board of education goals, all teachers and leaders continued to build an awareness of the Next Generation Learning Standards through a diverse professional development workshops offered by staff developers from around the country and members of the Cold Spring Harbor faculty. Professional development occurred in numerous content areas such as English Language Arts, math, social studies, science, and technology. Teachers also received professional learning in the revised New York State Standards for the Arts. These efforts continue to support many goals including the district’s work in building authentic research experiences for all students in kindergarten through graduation. In addition, our Science Research Program continued to flourish and its expansion provided students with practical experiences and even an opportunity to highlight their work at the Science Research Symposium at the high school, a true example of providing students with opportunities to share high level research with their peers and the community. While there are many highlights to the school year in relation to the district’s goals in the area of technology, the Creative Learning Labs assembled at the two elementary buildings provided students, teachers, and even parents the chance to experience a truly redefined classroom. Designed by teachers and leaders, these state-of-the-art spaces outfitted with flexible furniture, afforded students with the ability to experience enhanced and differentiated learning environments. -

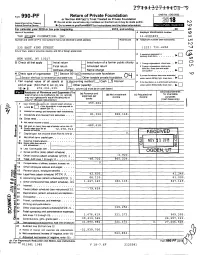

I Mmmmmmmm I I Mmmmmmmmm I M I M I Mmmmmmmmmm 5A Gross Rents

OMB No. 1545-0052 Form 990-PF Return of Private Foundation I or Section 4947(a)(1) Trust Treated as Private Foundation À¾µ¼ Do not enter social security numbers on this form as it may be made public. Department of the Treasury I Internal Revenue Service Go to www.irs.gov/Form990PF for instructions and the latest information. Open to Public Inspection For calendar year 2018 or tax year beginning 02/01 , 2018, and ending 01/31 , 20 19 Name of foundation A Employer identification number SALESFORCE.COM FOUNDATION 94-3347800 Number and street (or P.O. box number if mail is not delivered to street address) Room/suite B Telephone number (see instructions) 50 FREMONT ST 300 (866) 924-0450 City or town, state or province, country, and ZIP or foreign postal code C If exemption applicatmionm ism m m m m m I pending, check here SAN FRANCISCO, CA 94105 m m I G Check all that apply: Initial return Initial return of a former public charity D 1. Foreign organizations, check here Final return Amended return 2. Foreign organizations meeting the 85% test, checkm hem rem anmd am ttamchm m m I Address change Name change computation H Check type of organization: X Section 501(c)(3) exempt private foundation E If private foundation status was terminamtedI Section 4947(a)(1) nonexempt charitable trust Other taxable private foundation under section 507(b)(1)(A), check here I Fair market value of all assets at J Accounting method: Cash X Accrual F If the foundation is in a 60-month terminmatIion end of year (from Part II, col. -

Environmental Kuznets Curve Revisit: Role of Economic Diversity in Environmental Degradation

Environmental Kuznets Curve Revisit: Role of Economic Diversity in Environmental Degradation Raza Ghazal University of Kurdistan Mohammad Sharif Karimi ( [email protected] ) Razi University of Kermanshah: Razi University https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5967-6756 Bakhtiar Javaheri University of Kurdistan Research Keywords: Economic complexity, Structural change, Environmental Kuznets curve, Environmental degradation Posted Date: February 22nd, 2021 DOI: https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-213429/v1 License: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Read Full License 1 Environmental Kuznets Curve Revisit: Role of Economic Diversity in Environmental 2 Degradation 3 Raza Ghazal1 4 Mohammad Sharif Karimi2 5 Bakhtiar Javaheri3 6 7 8 Abstract 9 Background: Unlike the classical view, a new path of economic growth and development among 10 the emerging and developing nations seems to have distinct impact on environment. Customary 11 patterns of production and consumption have undergone significant changes and the new “growth 12 with non-smoke-staks” has put the developing economies on a path that can change Environmental 13 Kuznets Curve (EKC) fundamentally. With this view, the current study attempts to examine how 14 these growth patterns among developing world have impacted the degradation of environment. We 15 argue that including income per capita and share of manufacturing would not capture the full 16 growth dynamic of developing and emerging countries and therefore it masks the real impacts on 17 environmental degradation. To this end, we introduce the Economic Complexity Index (ECI) to 18 the model to reflect the full impacts of new growth approaches on CO2 emission levels by using a 19 panel data analyses of 100 emerging and developing countries over 1963-2018 period. -

Social Metabolism, Ecologically Unequal Exchange and Resource Extraction Conflicts in Latin America. Analytical Framework and Case Studies

Social metabolism, ecologically unequal exchange and resource extraction conflicts in Latin America. Analytical Framework and Case Studies Analytical Framework Report D.WP7 1 Deliverable WP7 1 – Analytical Framework Report Project Nº: 266710 Funding Scheme: Collaborative Project Objective: FP7‐SSH‐2010‐3 Status: Final version, 27/01/2012 Due date of delivery: 29/01/2012 Work Package: WP7 – Resource Extraction Conflicts Compared Leading Author: Mariana Walter and Joan Martinez Alier Co‐author(s): FP7 –SSH – 2010 – 3 GA 266710 Social metabolism, ecologically unequal exchange and resource extraction conflicts in Latin America. Analytical Framework and Case Studies Analytical Framework Report D.WP7.1 Table of Contents Summary & Key Words ........................................................................................................................... 3 Analytical Framework .............................................................................................................................. 4 Social Metabolism: A Biophysical Approach to the Economy ............................................................. 4 Material Flow Analysis ......................................................................................................................... 6 Ecologically Unequal Exchange ........................................................................................................... 7 Ecological distributive conflicts .......................................................................................................... -

Interdependence of Biodiversity and Development Under Global Change

Secretariat of the CBD Technical Series No. 54 Convention on Biological Diversity 54 Interdependence of Biodiversity and Development Under Global Change CBD Technical Series No. 54 Interdependence of Biodiversity and Development Under Global Change Published by the Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity ISBN: 92-9225-296-8 Copyright © 2010, Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity The designations employed and the presentation of material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity concern- ing the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The views reported in this publication do not necessarily represent those of the Convention on Biological Diversity. This publication may be reproduced for educational or non-profit purposes without special permission from the copyright holders, provided acknowledgement of the source is made. The Secretariat of the Convention would appreciate receiving a copy of any publications that use this document as a source. Citation Ibisch, P.L. & A. Vega E., T.M. Herrmann (eds.) 2010. Interdependence of biodiversity and development under global change. Technical Series No. 54. Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity, Montreal (second corrected edition). Financial support has been provided by the German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development For further information, please contact: Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity World Trade Centre 413 St. Jacques Street, Suite 800 Montreal, Quebec, Canada H2Y 1N9 Phone: +1 514 288 2220 Fax: +1 514 288 6588 Email: [email protected] Website: www.cbd.int Typesetting: Em Dash Design Cover photos (top to bottom): Agro-ecosystem used for thousands of years in the vicinities of the Mycenae palace (located about 90 km south-west of Athens, in the north-eastern Peloponnese, Greece). -

ANIMAL (DE)LIBERATION: Should the Consumption of Animal Products Be Banned? JAN DECKERS Animal (De)Liberation: Should the Consumption of Animal Products Be Banned?

ANIMAL (DE)LIBERATION: Should the Consumption of Animal Products Be Banned? JAN DECKERS Animal (De)liberation: Should the Consumption of Animal Products Be Banned? Jan Deckers ]u[ ubiquity press London Published by Ubiquity Press Ltd. 6 Windmill Street London W1T 2JB www.ubiquitypress.com Text © Jan Deckers 2016 First published 2016 Cover design by Amber MacKay Cover illustration by Els Van Loon Printed in the UK by Lightning Source Ltd. Print and digital versions typeset by Siliconchips Services Ltd. ISBN (Hardback): 978-1-909188-83-9 ISBN (Paperback): 978-1-909188-84-6 ISBN (PDF): 978-1-909188-85-3 ISBN (EPUB): 978-1-909188-86-0 ISBN (Mobi/Kindle): 978-1-909188-87-7 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.5334/bay This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Interna- tional License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons. org/licenses/by/4.0/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, 444 Castro Street, Suite 900, Mountain View, California, 94041, USA. This license allows for copying any part of the work for personal and commercial use, providing author attribution is clearly stated. The full text of this book has been peer-reviewed to ensure high academic standards. For full review policies, see http://www.ubiquitypress.com/ Suggested citation: Deckers, J 2016 Animal (De)liberation: Should the Consumption of Animal Products Be Banned? London: Ubiquity Press. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.5334/bay. License: CC-BY 4.0 To read the free, open access version of this book online, visit http://dx.doi.org/10.5334/bay or scan -

Climate Change – Predictions, Economic Consequences, and the Relevance Of

ISSN 1327-8231 ECONOMICS, ECOLOGY AND THE ENVIRONMENT Working Paper No. 188 Climate Change – Predictions, Economic Consequences, and the Relevance of Environmental Kuznets Curves by Clem Tisdell December 2012 THE UNIVERSITY OF QUEENSLAND ISSN 1327-8231 WORKING PAPERS ON ECONOMICS, ECOLOGY AND THE ENVIRONMENT Working Paper No. 188 Climate Change – Predictions, Economic Consequences, and the Relevance of Environmental Kuznets Curves1 by Clem Tisdell2 December 2012 © All rights reserved 1 Revised notes for the fifth and final guest lecture given in October, 2012 in the College of Life and Environmental Science, Minzu University of China, Beijing. I wish to thank Professor Dayuan Xue for inviting me to give these lectures. 2 School of Economics, The University of Queensland, St. Lucia Campus, Brisbane QLD 4072, Australia Email: [email protected] The Economics, Environment and Ecology set of working papers addresses issues involving environmental and ecological economics. It was preceded by a similar set of papers on Biodiversity Conservation and for a time, there was also a parallel series on Animal Health Economics, both of which were related to projects funded by ACIAR, the Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research. Working papers in Economics, Environment and Ecology are produced in the School of Economics at The University of Queensland and since 2011, have become associated with the Risk and Sustainable Management Group in this school. Production of the Economics Ecology and Environment series and two additional -

Building on Nature: Area-Based Conservation As a Key Tool for Delivering Sdgs

Area-based conservation as a key tool for delivering SDGs CITATION For the publication: Kettunen, M., Dudley, N., Gorricho, J., Hickey, V., Krueger, L., MacKinnon, K., Oglethorpe, J., Paxton, M., Robinson, J.G., and Sekhran, N. 2021. Building on Nature: Area-based conservation as a key tool for delivering SDGs. IEEP, IUCN WCPA, The Nature Conservancy, The World Bank, UNDP, Wildlife Conservation Society and WWF. For individual case studies: Case study authors. 2021. Case study name. In: Kettunen, M., Dudley, N., Gorricho, J., Hickey, V., Krueger, L., MacKinnon, K., Oglethorpe, J., Paxton, M., Robinson, J.G., and Sekhran, N. 2021. Building on Nature: Area-based conservation as a key tool for delivering SDGs. IEEP, IUCN WCPA, The Nature Conservancy, The World Bank, UNDP, Wildlife Conservation Society and WWF. CORRESPONDING AUTHORS Nigel Dudley ([email protected]) and Marianne Kettunen ([email protected]) PARTNERS Institute for European Environmental Policy (IEEP) IUCN World Commission on Protected Areas (WCPA) The Nature Conservancy (TNC) The World Bank Group UN Development Programme (UNDP) Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS) WWF DISCLAIMER The information and views set out in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect official opinions of the institutions involved. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This report and the work underpinning it has benefitted from the support of the following people: Sophia Burke (AmbioTEK CIC), Andrea Egan (UNDP), Marie Fischborn (PANORAMA), Barney Long (Re-Wild), Melanie McField (Healthy Reefs), Mark Mulligan (King’s College, London), Caroline Snow (proofreading), Sue Stolton (Equilibrium Research), Lauren Wenzel (NOAA), and from the many case study authors named individually throughout the publication. -

2018 Or Tax Year Beginning , 2018, and Endina Name of Foundation a Employer Ldentlf1catlon Number the PFJEER FOUNDATION, INC

Form 990-PF Return of Private Foundation or Section 4947(a)(1) Trust Treated as Private Foundation Department o,,t the Treasury ... Do not enter social security numbers on this form as it may be made public. Internal Revenue Service .,. Go to www.irs.gov/Fonn990PF for instructions and the latest information For ca endar vear 2018 or tax year beginning , 2018, and endina Name of foundation A Employer ldentlf1catlon number THE PFJEER FOUNDATION, INC. 13-6083839 Number and street (or PO box number 11 ma1l 1s not delivered to street address) Room/suite B Telephone number (see 1nstruct1ons) 235 EAST 42ND STREET ( 212) 733 -4250 City or town, state or province, country, and ZIP or foreign postal code C If exemption appllcat1on 1s pending, check here. • • NEW YORK, NY 10017 G Check all that apply Initial return ,___ Initial return of a former public charity D 1 Foreign organ1zat1ons. check here. ,___ Final return ~ Amended return 2 F ore1gn orgamzat1ons meeting the 85% test, check here and attach Address change Name change computat1on • • • • • • • • H Check type of organization X Section 501 (c)(3) exempt private foundation oy E If private foundation status was terminated D _.___.n __S.::.e.::.c::.:t::..:10:.:.n.:...4...:..::.94..;..7.:...'<:c:a:u..H1,_,, >...:n::..:o:..:n::..:e:::.x:.=e::..:m.:.,10:.:t....:c:.:.h:.=a::..:ri:.=ta:.:b:.:.le:;....::.tr.:::u.:::st:....__,_""._,_=O:.:t::..:h=e.:...r.:.ta=xa:;:=b:..::le;...c..:.:Pn.:.v::::ac:cte;....:.f.:::o.;:u::..:n.=d.=ac.::t1.:::o::..:n n ___ ..:__--l under section S07(b)(1)(A) check here .