Are Radio Markets Dirichlet? a Study Into the Nbd/Dirichlet, Its Empirical Generalisations and Their Extension to Radio

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

JMAD Media Ownership Report

JMAD New Zealand Media Ownership Report 2014 Published: 2014 December 5 Author: Merja Myllylahti This New Zealand Ownership Report 2014 is the fourth published by AUT’s Centre for Journalism, Media and Democracy (JMAD). The report finds that the New Zealand media market has failed to produce new, innovative media outlets, and that all the efforts to establish non-profit outlets have proved unsustainable. The report confirms the general findings of previous reports that New Zealand media space has remained highly commercial. It also confirms the financialisation of media ownership in the form of banks and fund managers. The report also observes that in 2014 convergence between New Zealand mass media and the communications sector generally was in full swing. Companies, such as Spark (former Telecom NZ), started to compete head-to-head with the traditional broadcasters on the online on-demand video and television markets. The American online video subscription service Netflix is entering the NZ market in March 2015. Additionally, the report notes evidence of uncomfortable alliances between citizen media, politicians, PR companies and legacy media. As Nicky Hager’s Dirty Politics book revealed, the National Party and PR practitioners used the Whale Oil blog to drive their own agendas. Also, events related to Maori TV, TVNZ and Scoop raise questions about political interference in media affairs. It is now evident that the boundaries between mainstream media, bloggers, public relations practitioners and politicians are blurring. Key events and trends concerning New Zealand media Financialisation of mass media ownership confirmed Substantial changes in Fairfax, APN and MediaWorks ownership Competition heats up in online television and video markets Turbulence at Maori TV Blurred lines among politicians, bloggers, journalists and PR practitioners The JMAD New Zealand media ownership reports are available here: http://www.aut.ac.nz/study- at-aut/study-areas/communications/media-networks/journalism,-media-and-democracy-research- centre/journalists-and-projects 1 1. -

New Zealand Broadcasting Formal Complaints System 1973–1988 PDF1.69 MB

NEW ZEALAND BROADCAST I NO FORMAL COMPLAINTS SYSTEM 1 «P:?»3 — 1 <5>SS PREPARED FOR THE BROADCASTING STANDARDS AUTHORITY BY I H MCLEAN SEPTEMBER 1989 CONTENTS PAGE SUMMARY i 1 INTRODUCTORY COMMENT 1 2 LEGISLATIVE HISTORY Broadcasting Act 1973 1 Broadcasting Act 1976 2 - Public Broadcasting 2 - Private broadcasting 3 - Philosophy o-f- the Act 3 - Broadcasting Tribunal 4 Broadcasting Amendment Act 1982 6 - Broadcasting Complaints Committee 7 - Power of Referral 9 - Public i ty 9 - Broadcasting Tribunal 9 3 PUBLICATION OF COMPLAINTS SYSTEM 10 4 NUMBERS AMD TYPES OF COMPLAINTS 10 5 PROCEDURES AMD ADMINISTRATION - Broadcasting Council 11 - Private Stations and Committee o-f Private Broadcasters 12 - Broadcasting Corporation of New Zealand 12 - Broadcasting Complaints Committee 14 - Broadcasting Tribunal 14 6 COMMENT - Definition of "Formal" Complaint 17 - Refusal of Complaints 17 - Delays IS - Payment 19 - Publication of Decisions 20 - Campaigns 21 APPENDICES Formal Complaints Considered by - Broadcasting Tribunal Appendix A Broadcasting Complaints Committee Appendix B Broadcasting Council Z< Corporation Appendix C Committee of Private Broadcasters Appendix D ENCLOSURES "Radio and Television in New Zealand" (1973) "Radio and Television in New Zealand" <1983) "Broadcasting in New Zealand - Your Rights" (1935) NEW ZEALAND BROADCASTING FORMAL COMPLAINTS SYSTEM SUMMARY < I ) THE FIRST LEGISLATED BROADCASTING COMPLAINTS procedure, IN THE BROADCASTING ACT 1973, CONCERNED UNJUST AND UNFAIR TREATMENT BY PUBLIC BROADCASTING corporations. IT WAS ADMINISTERED BY THE BROADCASTING COUNCIL OF NEW zealand. \ I I ) THE BROADCASTING ACT 1976 EXTENDED THE GROUNDS FOR COMPLAINT TO INCLUDE PROGRAMME standards, AND APPLIED ALSO TO PRIVATE broadcasters. IT WAS PART OF THE SYSTEM OF ACCOUNTABILITY OF THE BROADCASTING INDUSTRY which, UNDER THE act, WAS GIVEN CONSIDERABLE SE1F-regu1 ATION. -

Submission On: Exploring Digital Convergence- Issues for Policy and Legislation and Content Regulation in a Converged World

Submission on: Exploring Digital Convergence- issues for policy and legislation and Content Regulation in a Converged World October 2015 1 Preamble The Coalition for Better Broadcasting1 welcomes the opportunity to comment on the Exploring Digital Convergence- issues for policy and legislation and Content Regulation in a Converged World discussion documents. The following submission encompasses responses to both papers. Given that the regulatory issues overlap on several practical and conceptual levels, the submission pertains to both and we would ask that the comments be taken into consideration in any deliberations stemming from both the convergence documents and, where relevant, the review of telecommunications legislation (see comments in sections 2 and 5). We are pleased that the government has decided to address the regulatory questions stemming from convergence, especially since the earlier (2008) government initiative Digital Broadcasting- Review of Regulation2, which was intended to address many of the issues the current consultation covers, was cut short in 2009 after a limited review of competition issues. Given the complexities of the convergence-related issues to be addressed, we have to observe that the time-frame for stakeholder response has significantly constrained the opportunities for a more fulsome response, and given the that selected industry stakeholders were reportedly consulted at earlier points in the process of formulating this framework, we are concerned that groups representing civil society appear not to have had an equal opportunity to engage. Given the experience and expertise of the CBB’s board and their independence from vested commercial interests, we would be keen to participate in any future consultations and would appreciate being kept informed about the time-frames for the planned review of issues emerging from these consultations. -

Research in the Spotlight What Am I Discovering?

RESEARCH IN THE SPOTLIGHT WHAT AM I DISCOVERING? side of the world to measure the effects of poi on UNINEWS highlights some of the University physical and cognitive function in a clinical trial. research milestones that have hit the I wanted to discover how science and culture headlines in the past couple of months. might meet, and what they might say to each other about a weight orbiting on the end of a FISHING string. A study that exposed six decades of Working between the Centre for Brain widespread under reporting and dumping of Research and Dance Studies, the first round of marine fish has been covered extensively in an assessor-blind randomised control trial has the media. Lead researcher Dr Glenn Simmons just concluded. Forty healthy adults over 60 from the New Zealand Asia Institute at the years old participated in a month of International Business School appeared on Nine To Noon, Poi lessons (treatment group) or Tai Chi lessons Paul Henry, Radio Live, NewsHub and One (control group), and underwent a series of News, and was quoted in print and online. The pre- and post-tests measuring things like research, part of a decade-long, international balance, upper limb range of motion, bimanual project to assess the total global marine catch, coordination, grip strength, and cognitive put the true New Zealand catch at 2.7 times flexibility. Feedback from the participants official figures. after their International Poi lessons has been exciting: “Positive on flexibility, stress release, coordination and concentration. Totally, totally GRADUATION positive. Mental and physical.” “I am able to AGING GRACEFULLY use my left wrist more freely, and I am focusing The story of 84-year-old Nancy Keat, oldest better. -

Radio Frequency Tender: Provisional Results

SUPPLEMENT to ~ 15 The New Zealand azette OF THURSDAY, 10 JANUARY 1991 WELLINGTON: FRIDAY, 11 JANUARY 1991 - ISSUE NO.2 RADIO FREQUENCY TENDER: PROVISIONAL RESULTS 11 JANUARY NEW ZEALAND GAZETTE 17 COMMERCE RADIO FREQUENCY TENDERING XINISTRY OF COMMERCE : TENDER FOR SOUND BROADCASTING FREQUENCY RIGHTS The following notice is a list of provisional successful tenderers who tendered under the call for tenders in respect of AM and FM Sound Broadcasting Frequency Rights issued on 26 July 1990. Confirmation will follow any necessary clearances or authorisations under the Commerce Act 1986, where applicable, and payment in settlement, where required, by the tenderers concerned. Final results for lots will be published in detail in the New Zealand Gazette as soon as practicable. LOT NO PROVISIONAL SUCCESSFUL TENDERERS LOCATION AM/ FM 013JAC RADIO RHEMA INCORPORATED CHRISTCHURCH AM 014JAD RADIO RHEMA INCORPORATED WAIPAPAKAURI AM OlSJAE RFC BROADCASTERS TAUPO AM O16JAF RADIO RHEMA INCORPORATED BLENHEIM AM 017JAG RADIO RHEMA INCORPORATED NEW PLYMOUTH AM 018JAH RADIO RHEMA INCORPORATED CHATHAM ISLANDS AM 019JAI RADIO RHEMA INCORPORATED WHANGAREI AM 020JBJ RADIO RHEMA INCORPORATED GREYMOUTH AM 021JBA RADIO RHEMA INCORPORATED DUNEDIN AM 022JBB TOTALISATOR AGENCY BOARD (TAB) TITAHI BAY AM 023JBC RADIO RHEMA INCORPORATED NEW PLYMOUTH AM 024JBD RADIO RHEMA INCORPORATED HAMILTON AM 02SJBE TOTALISATOR AGENCY BOARD (TAB) TAURANGA AM 026JBF RADIO RHEMA INCORPORATED WHANGAREI AM 028JBH RADIO RHEMA INCORPORATED OAMARU AM 029JBI FIFESHIRE FM BROADCASTERS LIMITED -

DX Times Master Page Copy

N.Z. RADIO New Zealand DX Times N.Z. RADIO Monthly journal of the D X New Zealand Radio DX League (est. 1948) D X April 2003 - Volume 55 Number 6 LEAGUE http://radiodx.com LEAGUE . As Radio Hobbyists (DX’ers or Listeners) we are able to tune into Shortwave broadcasts from countries involved in the Iraqi conflict or neighbouring countries. Whether you agree or disagree with what has occurred, we are fortunate to be able to listen to those differing viewpoints and make up our own minds. You will find a list of English Broadcast frequencies from countries involved in the Iraqi conflict and its neighbours, compiled by Paul Ormandy on page 17, plus the normal ‘Unofficial Radio’ ‘Under 9’ & ‘Over 9’ Bandwatch columns and ‘Shortwave Report’ Contribution deadline for next issue is Wed 7th May 2003 PO Box 3011, Auckland Some of the International Broadcasters also CONTENTS have thought provoking comments or editorials about the conflict such as the editorial by Andy Sennitt on REGULAR COLUMNS the Radio Netherlands website at Bandwatch Under 9 3 http://www.rnw.nl/realradio/features/html/editorial.html with Ken Baird The Iraqi conflict has also shown that Bandwatch Over 9 6 Shortwave Radio is still a powerful tool, for general with Andy McQueen news and discussion and also as a Propaganda Shortwave Report 10 with Ian Cattermole outlet. English in Time Order 20 An interesting article as mentioned in the with Yuri Muzyka Unofficial Radio pages concerning Commando Solo Shortwave Mailbag 23 missions by the U.S. Air Force EC-130E aircraft and with Paul Ormandy other special forces broadcasts is on the dxing.info Utilities 25 website at. -

Palmerston North Radio Stations

Palmerston North Radio Stations Frequency Station Location Format Whanganui (Bastia Hill) Mainstream Radio 87.6 FM and Palmerston rock(1990s- 2018 Hauraki North (Wharite) 2010s) Palmerston Full service iwi 89.8 FM Kia Ora FM Unknown Unknown North (Wharite) radio Palmerston Contemporary 2QQ, Q91 FM, 90.6 FM ZM 1980s North (Wharite) hits ZMFM Palmerston Christian 91.4 FM Rhema FM Unknown North (Wharite) contemporary Palmerston Adult 92.2 FM More FM 1986 2XS FM North (Wharite) contemporary Palmerston Contemporary 93.0 FM The Edge 1998 Country FM North (Wharite) Hit Radio Palmerston 93.8 FM Radio Live Talk Radio Unknown Radio Pacific North (Wharite) Palmerston 94.6 FM The Sound Classic Rock Unknown Solid Gold FM North (Wharite) Palmerston 95.4 FM The Rock Rock Unknown North (Wharite) Palmerston Hip Hop and 97.0 FM Mai FM Unknown North (Wharite) RnB Classic Hits Palmerston Adult 97.8 FM The Hits 1938 97.8 ZAFM, North (Wharite) contemporary 98FM, 2ZA Palmerston 98.6 FM The Breeze Easy listening 2006 Magic FM North (Wharite) Palmerston North Radio Stations Frequency Station Location Format Radio Palmerston 99.4 FM Campus radio Unknown Radio Massey Control North (Wharite) Palmerston 104.2 FM Magic Oldies 2014 Magic FM North (Wharite) Vision 100 Palmerston 105.0 FM Various radio Unknown Unknown FM North (Kahuterawa) Palmerston Pop music (60s- 105.8 FM Coast 2018 North (Kahuterawa) 1970s) 107.1 FM George FM Palmerston North Dance Music Community 2XS, Bright & Radio Easy, Classic 828 AM Trackside / Palmerston North TAB Unknown Hits, Magic, TAB The Breeze Access Triple Access Community Nine, 999 AM Palmerston North Unknown Manawatu radio Manawatu Sounz AM Pop Palmerston 1548 AM Mix music (1980s- 2005 North (Kahuterawa) 1990s) Palmerston North Radio Stations New Zealand Low Power FM Radio Station Database (Current List Settings) Broadcast Area: Palmerston North Order: Ascending ( A-Z ) Results: 5 Stations Listed. -

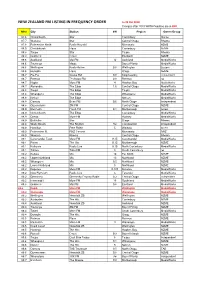

NZL FM Master List to Oct18

NEW ZEALAND FM LISTING IN FREQUENCY ORDER to 29 Oct 2018 Changes after 2019 WRTH Deadline are in RED MHz City Station kW Region Owner/Group 87.6 Christchurch Star Canterbury Rhema 87.7 Wanaka Star Central Otago Rhema 87.8 Palmerston North Radio Hauraki Manawatu NZME 88.0 Christchurch Flava Canterbury NZME 88.3 Taupo Star Taupo Rhema 88.3 Gisborne Coast Eastland NZME 88.6 Auckland Mai FM 10 Auckland MediaWorks 88.6 Tauranga Magic Bay of Plenty MediaWorks 88.6 Wellington Radio Active 0.5 Wellington Student 88.6 Dunedin Flava Otago NZME 88.7 Pio Pio Cruise FM 0.8 King Country Independent 88.7 Rotorua Te Arawa FM 0.8 Rotorua Iwi 88.7 Napier More FM 4 Hawkes Bay MediaWorks 88.7 Alexandra The Edge 1.6 Central Otago MediaWorks 88.8Taupo The Edge Taupo MediaWorks 88.8 Whanganui The Edge Whanganui MediaWorks 88.8 Nelson The Edge Nelson MediaWorks 88.8 Oamaru Brian FM 0.6 North Otago Independent 88.8 Queenstown ZM-FM Central Otago NZME 88.9 Blenheim Fresh FM 0.1 Marlborough Access 88.9 Christchurch The Edge Canterbury MediaWorks 88.9 Orewa More FM Rodney MediaWorks 88.9 Balclutha Star Otago Rhema 89.0 Waihi Beach The Rhythm 8w Coromandel Independent 89.0 Hamilton Free FM89 5 Waikato Access 89.0 Palmerston N. RNZ Concert Manawatu RNZ 89.0 Wanaka Rhema Central Otago Rhema 89.1 Coromandel Town More FM 0.15 Coromandel MediaWorks 89.1 Picton The Hits 0.15 Marlborough NZME 89.1 Kaikoura Radio Live 0.15 North Canterbury MediaWorks 89.1 Timaru Tahu FM 5 South Canterbury Iwi 89.2 Kaitaia Mix 10 Far North NZME 89.2 Upper Northland Mix 10 Northland NZME 89.2 -

Stations Monitored

Stations Monitored 10/01/2019 Format Call Letters Market Station Name Adult Contemporary WHBC-FM AKRON, OH MIX 94.1 Adult Contemporary WKDD-FM AKRON, OH 98.1 WKDD Adult Contemporary WRVE-FM ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY, NY 99.5 THE RIVER Adult Contemporary WYJB-FM ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY, NY B95.5 Adult Contemporary KDRF-FM ALBUQUERQUE, NM 103.3 eD FM Adult Contemporary KMGA-FM ALBUQUERQUE, NM 99.5 MAGIC FM Adult Contemporary KPEK-FM ALBUQUERQUE, NM 100.3 THE PEAK Adult Contemporary WLEV-FM ALLENTOWN-BETHLEHEM, PA 100.7 WLEV Adult Contemporary KMVN-FM ANCHORAGE, AK MOViN 105.7 Adult Contemporary KMXS-FM ANCHORAGE, AK MIX 103.1 Adult Contemporary WOXL-FS ASHEVILLE, NC MIX 96.5 Adult Contemporary WSB-FM ATLANTA, GA B98.5 Adult Contemporary WSTR-FM ATLANTA, GA STAR 94.1 Adult Contemporary WFPG-FM ATLANTIC CITY-CAPE MAY, NJ LITE ROCK 96.9 Adult Contemporary WSJO-FM ATLANTIC CITY-CAPE MAY, NJ SOJO 104.9 Adult Contemporary KAMX-FM AUSTIN, TX MIX 94.7 Adult Contemporary KBPA-FM AUSTIN, TX 103.5 BOB FM Adult Contemporary KKMJ-FM AUSTIN, TX MAJIC 95.5 Adult Contemporary WLIF-FM BALTIMORE, MD TODAY'S 101.9 Adult Contemporary WQSR-FM BALTIMORE, MD 102.7 JACK FM Adult Contemporary WWMX-FM BALTIMORE, MD MIX 106.5 Adult Contemporary KRVE-FM BATON ROUGE, LA 96.1 THE RIVER Adult Contemporary WMJY-FS BILOXI-GULFPORT-PASCAGOULA, MS MAGIC 93.7 Adult Contemporary WMJJ-FM BIRMINGHAM, AL MAGIC 96 Adult Contemporary KCIX-FM BOISE, ID MIX 106 Adult Contemporary KXLT-FM BOISE, ID LITE 107.9 Adult Contemporary WMJX-FM BOSTON, MA MAGIC 106.7 Adult Contemporary WWBX-FM -

BSA DECISIONS ISSUED SUMMARY for the Quarter July to September

BSA DECISIONS ISSUED SUMMARY for the Quarter July to September Upheld No. Complainant Broadcaster Programme Nature of the complaint Standards Finding 2008-036 Hammond TVNZ Eyes Wide Shut Movie containing sex scenes, language, drug use Children's interests Upheld 2008-032 Findlay TVNZ Rome Historical drama contained course language Good taste and decency Upheld 2007-138 LM TVNZ Skin Doctors Woman undergoing breast augmentation Privacy Upheld 2008-040 Pryde RNZ Nine to Noon Update on situation in Fiji Accuracy, balance Upheld (accuracy) 2008-066 Harrison TVNZ Ugly Betty Contained sexual themes Programme classification, Upheld promo children's interests, good (programme taste and decency classification and children's interests) 2008-039A Nudds TVNZ Wolf Creek Horror film with disturbing violence Violence, Children's Upheld (violence) interests, good taste and decency 2008-039B McIntosh TVNZ Wolf Creek Horror film with disturbing violence Violence, Children's Upheld (violence) interests, good taste and decency Not Upheld No. Complainant Broadcaster Programme Nature of the complaint Standards Finding 2008-041 Scott TVWorks Ltd 3 News Report that celebrity had obtained diversion for Privacy Not Upheld shoplifting 2008-030 Blazey TVWorks Ltd 3 News Item showed clothed body of dead teenager Good taste and decency Not Upheld 2008-017 South Pacific RadioWorks Radio Live Host disclosed address of house used in TV Privacy Not Upheld Pictures Ltd programme 2008-027 FitzPatrick TVNZ Close Up Discussion about ASA ruling Balance Not Upheld 2008-042 Clancy -

2018 RBA Annual Report

2 018 RADIO BROADCASTERS ASSOCIATION ANNUAL REPORT www.rba.co.nz THE YEAR BY NUMBERS NUMBER OF PEOPLE EMPLOYED BY RBA COMMERCIAL STATIONS – IN THE REGION OF 1,800 ANNUAL RADIO REVENUE $ 279.4 MILLION % OF ALL NZ ADVERTISING REVENUE 10.63% # OF COMMERCIAL RADIO FREQUENCIES– 103 AM & 678 FM 781 # OF LISTENERS AGED 10+ TO ALL RADIO AS AT S4 DECEMBER 2018 84% OF ALL NEW ZEALANDERS* 3.59 MILLION # OF LISTENERS AGED 10+ TO COMMERCIAL RADIO AS AT S4 DECEMBER 2018 78% OF ALL NEW ZEALANDERS* 3.32 MILLION # OF RADIO STUDENTS IN 2018 With almost 3.6 million people listening to radio each week and 3.3 million of those listening to commercial radio, we are one 173 of, if not the most used media channels every week in New Zealand. We need to shout this loudly and proudly. Jana Rangooni, RBA CEO www.rba.co.nz FROM THE RBA CHAIRMAN, FROM THE RBA CEO, NORM COLLISON JANA RANGOONI 2018 was a challenging As I write our support of a thriving mainstream year for all organisations in this report music industry in New Zealand. the media throughout New I, like so • We have revised the radio agency Zealand as we faced more many in the accreditation scheme and increased competition at a global level. industry, the number of agencies participating. It was pleasing therefore to are still see radio yet again hold its grieving • We have developed a new plan own in terms of audiences the loss with Civil Defence to engage with and advertising revenue. of our the 16 CDEM regions to ensure the Memorandum of Understanding with We ended the year with over 3.3 million New Zealanders colleague Darryl Paton who so many MCDEM is activated across New listening to commercial radio each week and $279.4 million in know from his years at The Edge and The Zealand. -

Celebrate New Zealand Music Month in Your Classroom

! !"#"$%&'"()*(+,-.!(/01/! 1! "! • All primary schools have the Kiwi Kids Songs series - #5 has ‘Nature’ in a good key, ‘Dance all around the world’ (#10) and so on... Older students may enjoy songs in “Sweet 2”. There is the MOE’s Hirini Melbourne resource and in recent years, Kiwi Kids Songs #15 for heaps of Waiata. The Patea hit, “Poi E” is on Nature’s Best – available everywhere and universally liked as well, it made a big come back ‘cos of the film “BOY” ... (and in Sweet 2 with a lead sheet for year 7s up) Kiwikids Songs #16 – are all Pasifica songs Volume # 17 (Values) has Tim Finn’s “Couldn’t be done” and other goodies... • Get “Ihimaera” – this album created in !!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!! ! 2011 is awesome. All the lyrics are by Witi Ihimaera and set by some of NZ’s most talented artists, Including Kapisi, Ruia Aperahama, Victoria Girling-Butcher (Lupin), #$%$&'()$!*$+!,$(%(-.!/0123! Charlotte Yates and others : www.smokecds.com/cd/47401 /4-)5!2-!640'!3%(11'4478! This has great cross-curricula lesson possibilities – lyrics cf. prose discussions for • “Anika (Moa) to Zowie” - compile an A to Z starters. list of NZ recorded artists • Stream Kiwi Fm’s “31Bands in a Box” – (www.nzmusic.org.nz/nzartists has a good Yes happening again in 2012 - daily list for starters) interviews and performances with NZ artists... A similar exploration of NZ band names on the net – and archived. by number (1814, six60 …how many See : www.kiwifm.co.nz more?) (dial-up and broadband options) • Sing lots of great NZ songs! You might start with the songs written by • Study NZ POP history –Nature’s Best covers students and chosen for Hook Line and Sing- the decades very well over 3 CDs (and along on the 31st May; chosen as the song of there’s a DVD and the sheet music available NZ Music Month 2012, “21 Degrees”, or for most tracks).