Connecticut Newspapers in the Eighteenth Century

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Yale University Catalogue, 1865 Yale University

Yale University EliScholar – A Digital Platform for Scholarly Publishing at Yale Yale University Catalogue Yale University Publications 1865 Yale University Catalogue, 1865 Yale University Follow this and additional works at: http://elischolar.library.yale.edu/yale_catalogue Part of the Curriculum and Instruction Commons, and the Higher Education Commons Recommended Citation Yale University, "Yale University Catalogue, 1865" (1865). Yale University Catalogue. 53. http://elischolar.library.yale.edu/yale_catalogue/53 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Yale University Publications at EliScholar – A Digital Platform for Scholarly Publishing at Yale. It has been accepted for inclusion in Yale University Catalogue by an authorized administrator of EliScholar – A Digital Platform for Scholarly Publishing at Yale. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CATALOGUE OF THE OFFICERS AND STUDENTS IN' YALE OOLLEG E, WITH A STATEMENT OF THE COURSE OF INSTRUC'riON IN THE VARIOUS DEPART.l\IE~TS. 1865- 66. NEW ITAVEN: PRIXTED BY E. HAYES, 426 CHAPEL ST. 1865. 2 \ ~o:~po~attou. THE GOVERXOR, LIEUTE!'lANT GOVERNOR, AND SIX SENIOR SENATORS OF THE STAT£ &RE, ez officio, MEMBERS OF THE CORPORATION. PB.ES:IDENT • . REv. THEODORE D. WOOLSEY, D.D., LL.D. FELLOWS. H1s Exc. WILLIAM A. BUCKINGHAM, NoRWicH. His HoNOR ROGER AVERILL, DANBURY. REv. JEREMIAH DAY, D. D., LL.·D., NEw HAVEN. REv. JOEL HAWES, D. D., HARTFORD. REv. JOSEPH ELDRIDGE, D. D., NoRFOLK. REv. GEORGE J. TILLOTSON, PuTNAM. REV. EDWIN R. GILBERT, WALLINGFORD. REV. JOEL H. LINSLEY, D. D., GREENWICH. REv. DAVIS S. BRAINERD, LYME. REV. JOHN P. GULLIVER. NoRWICH. REv. ELISHA C. -

“Extracts from Some Rebel Papers”: Patriots, Loyalists, and the Perils of Wartime Printing

1 “Extracts from some Rebel Papers”: Patriots, Loyalists, and the Perils of Wartime Printing Joseph M. Adelman National Endowment for the Humanities Fellow American Antiquarian Society Presented to the Joint Seminar of the McNeil Center for Early American Studies And the Program in Early American Economy and Society, LCP Library Company of Philadelphia, 1314 Locust Street, Philadelphia 24 February 2012 3-5 p.m. *** DRAFT: Please do not cite, quote, or distribute without permission of the author. *** 2 The eight years of the Revolutionary War were difficult for the printing trade. After over a decade of growth and increasing entanglement among printers as their networks evolved from commercial lifelines to the pathways of political protest, the fissures of the war dispersed printers geographically and cut them off from their peers. Maintaining commercial success became increasingly complicated as demand for printed matter dropped, except for government printing, and supply shortages crippled communications networks and hampered printers’ ability to produce and distribute anything that came off their presses. Yet even in their diminished state, printers and their networks remained central not only to keeping open lines of communication among governments, armies, and civilians, but also in shaping public opinion about the central ideological issues of the war, the outcomes of battles, and the meaning of events affecting the war in North America and throughout the Atlantic world. What happened to printers and their networks is of vital importance for understanding the Revolution. The texts that historians rely on, from Common Sense and The Crisis to rural newspapers, almanacs, and even diaries and correspondence, were shaped by the commercial and political forces that printers navigated as they produced printed matter that defined the scope of debate and the nature of the discussion about the war. -

Indiana Magazine of History Volume Xxxv March, 1939 Number1

INDIANA MAGAZINE OF HISTORY VOLUME XXXV MARCH, 1939 NUMBER1 Land Policy and Tenancy in the Prairie Counties of Indiana* PAULWALLACE GATES The great prairie section of Indiana stretching from the Wabash to the Kankakee today challenges the attention of agricultural economists and social planners because of the high rate of farm tenancy, the large average size of farms, the declining population of the rural areas, the poor tenant homes that do not harmonize with the richness of the sur- rounding soil, and a type of farming which for two gener- ations has been depleting the soil and reducing its ferti1ity.l This section, a continuation of the Grand Prairie of Illi- nois, has had an agricultural history sharply different from that of southern Indiana. In three prairie counties, Benton, Newton, and White, more than half of the farms are oper- ated by tenants and in three others, Jasper, Warren and Tip- pecanoe, over 40% are tenant operated. On the Illinois side of the Grand Prairie the rate of tenancy is even higher. Contrast this with the sixteen counties in southern Indiana which have less than 20% of their farms operated by tenants The largest farms in Indiana are also to be found in the prairie counties. Two farms totalling over 17,000 acres are reported from Newton County, and Jasper and Newton each contain eleven other farms over 1,000 acres in size. In Benton and Newton Counties, the average size of farms is well over 200 acres, and, in White, Warren and Jasper, it is over 160 acres. In few southern counties does the average size of farms exceed 125 acres. -

Appendix 5. Microfilmed Materials Not in Stiles Papers. Ezra Stiles Papers

Appendix 5. Microfilmed Materials Not in Stiles Papers This list contains brief descriptions of materials in Yale repositories relating to Ezra Stiles that are not located in the Stiles Papers but were included in the 1978 microfilm edition of the Papers. Locations of originals include collections held by the Beinecke Library, Yale University Library Manuscripts and Archives, and unidentified locations. Generally, descriptions and locations of originals are recorded as found on reference folders and microfilm targets removed from the Stiles Papers and discarded during processing in 2018. This list may be incomplete, and information identifying repositories, collections, and call numbers may be abbreviated or incomplete. Descriptions and locations of originals have not been verified. This list is organized by series, and files are in order as found in each series in the microfilm edition. Microfilm item numbers are recorded for items filmed as part of the Miscellaneous Volumes and Papers Series (MVP #) and the Sermons Series (SER #). Series I. Correspondence Baldwin, Simeon. To ES, 1782 October Yale University Library Manuscripts and Archives Hist MSS Baldwin Baldwin, Simeon. To George W. Prescott, 1804 December 17 Yale University Library Manuscripts and Archives Hist MSS Baldwin Benedict, Thomas. From ES, 1791 July 28 Yale University Library Manuscripts and Archives Hist MSS Baldwin Benedict, Thomas. To ES, 1791 August 1 Yale University Library Manuscripts and Archives Hist MSS Baldwin Broome, John (1738-1810). To James Hillhouse, 1789 March 27 Yale University Library Manuscripts and Archives Yale Treasurer Congregational Church (Medway, Ga.). To ES, 1785 July 23 Yale College Records Ely, Zebulon. To Yale College Corporation, 1781 November 2 Yale University Library Manuscripts and Archives Yale Treasurer Everitt, Daniel. -

From Apprentice to Journeyman to Partner: Benjamin Franklin's Workers and the Growth of the Early American Printing Trade

From Apprentice to Journeyman to Partner: Benjamin Franklin's Workers and the Growth of the Early American Printing Trade The lyf so short, the craft so long to lerne. —Geoffrey Chaucer, "The Parliament of Fowls" ANY APPRENTICES IN THE EARLY American printing trade must have felt as Chaucer's fabled craftsman did. Beginning M at a young age, they commonly spent up to seven years as contractually bound, unpaid laborers. They usually had to promise not to gamble, fornicate, frequent taverns, marry, and buy or sell or divulge secrets of the business. Apprentices worked long hours, often performed menial tasks, and were subjected to beatings—all without pay. Yet apprentices endured the arduous existence because it held for them the promise of eventual self-employment. Their goal was to learn a craft they could practice when their apprenticeship expired.1 The apprenticeship system was essential to the growth of the early American press. Apprenticeships to printers were a means of vocational education that replenished and augmented the craft's practitioners, thus insuring a sufficient supply of skilled labor through which the "art" (special skill) and the "mystery" (special knowledge) of printing 1 For an example of the apprentice's obligations, see Samuel Richardson, The Apprentice's Vade Mecum (1734j reprint ed., Los Angeles, 1975), 2-20. On the menial nature of some tasks, see O. Jocelyn Dunlop and Richard D. Denman, English Apprenticeship and Child Labour: A History (London, 1912), 19-20; Sharon V. Salinger, "To Serve Well and Faithfully": Labor and Indentured Servants in Pennsylvania, 1682-1800 (Cambridge, 1987), 7. -

American Panorama 150 Years of American History 1730 to 1880

CATALOGUE THREE HUNDRED SIXTY-FIVE American Panorama 150 Years of American History 1730 to 1880 WILLIAM REESE COMPANY 409 Temple Street New Haven, CT 06511 (203) 789-8081 A Note This catalogue, presented chronologically, includes 150 items spanning 150 years of American history, from 1730 to 1880. Comprised of books, pamphlets, manu- scripts, prints, maps, and photographs, one item has been selected for each year, helping to tell the multifaceted story of the development of the area that became the United States. Beginning with Herman Moll’s famous “Beaver Map” of the British colonies in America and concluding with an appeal to aid destitute African- American women and children in the post-Reconstruction era, the broad sweep of the American experience over a century and a half is represented. Included are works on politics, colonial development, law, military and diplomatic affairs, travel and exploration, sermons, westward expansion, contemporary historical accounts, scientific studies, improvements in technology and agriculture, images of urban and country life, and items relating to African-Americans (enslaved and free) and Native American tribes. In all, a panoramic view of 150 years of American history. Available on request or via our website are our bulletins as well as recent catalogues 361 Western Americana, 362 Recent Acquisitions in Americana, and 363 Still Cold: Travels & Explorations in the Frozen Regions of the Earth. E-lists, only available on our website, cover a broad range of topics including theatre, education, mail, the Transcontinental Railroad, satire, and abolition. A portion of our stock may be viewed on our website as well. Terms Material herein is offered subject to prior sale. -

Aprons Instead of Uniforms: the Practice of Printing, 1776-1787

Aprons Instead of Uniforms: The Practice of Printing, 1776-1787 ROLLO G. SILVER WE DO NOT think of a master printer as primarily a busi- nessman. Because he controls a major channel of communica- tion, our tendency is to romanticize him while we forget that essentially his chief concern is the same as that of his fellow tradesmen—the bottom line of his balance sheet. In time of war, his hazard is doubled. Then all businessmen face the problems of scarcity, financing, possibility of dislocation, per- haps survival, but the printer also has the government and the public closely involved in his activities. The government uses some of his work and needs all of his support; the public assiduously heeds the opinions expressed in his publications. When the war is a civil war, such as the American Revolu- tion was in part, his predicament is even more hazardous. Maintaining a printing shop despite changes in civil authority requires ingenuity as well as tenacity and, if one holds to one's principles, courage. After all, the printer is a business- man whose stock in trade consists of twenty-six lead soldiers. It is impractical to describe all the aspects of the practice of printing during this period in one chronological narrative. So it is preferable to select those topics which best depict the activities of the printers between 1776 and 1787. These topics include the relationship between printers and the Continental Congress and the relationship between printers and the state legislatures. The expansion of the press must be considered 111 112 American Antiquarian Society as well as the impact of the Revolution on the equipment and personnel of the shop. -

Table of Contents Trustees

Volume 11, Issue 2 Goodrich Family Association Quarterly June 12, 2014 Page 23 Table of Contents Trustees .......................................................................................................................................... 1 Goodrich Family Association DNA Project .............................................................................. 24 “What hath God wrought!” The message from Annie Goodrich Ellsworth ......................... 25 Fanny Goodrich, Lost Daughter of Asa (1765-1819), and Her Descendants ........................ 27 Asa Friend Goodrich, Physician ................................................................................................ 36 Goodrich Family Association Research Resources .................................................................. 43 Benefits of Membership in the Goodrich Family Association ................................................ 45 Goodrich Family Association Membership Application ......................................................... 47 Visit our website at www.GoodrichFamilyAssoc.org Trustees Delores Goodrick Beggs President; Genealogist/Historian; [email protected] DNA Project Manager; Trustee Matthew Goodrich Vice President; GFA Website; [email protected] DNA Project Website; Trustee Kay Waterloo Treasurer; Quarterly Editor; [email protected] Trustee Michelle Hubenschmidt Membership Chairman; Trustee [email protected] Carole McCarty Trustee [email protected] Carl Hoffstedt Trustee [email protected] Stephen Goodrich Trustee [email protected] -

Immigrant Printers and the Creation of Information Networks in Revolutionary America Joseph M. Adelman Program in Early American

1 Immigrant Printers and the Creation of Information Networks in Revolutionary America Joseph M. Adelman Program in Early American Economy and Society The Library Company of Philadelphia A Paper Submitted to ―Ireland, America, and the Worlds of Mathew Carey‖ Co-Sponsored by: The McNeil Center for Early American Studies The Program in Early American Economy and Society The Library Company of Philadelphia, The University of Pennsylvania Libraries Philadelphia, PA October 27-29, 2011 *Please do not cite without permission of the author 2 This paper is a first attempt to describe the collective experience of those printers who immigrated to North America during the Revolutionary era, defined here as the period between 1756 and 1796. It suggests these printers integrated themselves into the colonial part of an imperial communications structure and then into a new national communications structure in order to achieve business success. Historians have amply demonstrated that the eighteenth century Atlantic economy relied heavily on the social and cultural capital that people amassed through their connections and networks.1 This reliance was even stronger in the printing trade because the trade depended on the circulation of news, information, and ideas to provide the raw material for its products. In order to be successful, one had to cultivate other printers, ship captains, leading commercial men, and far-flung correspondents as sources of news and literary production. Immigrants by and large started at a slight disadvantage to their native-born competitors because they for the most part lacked these connections in a North American context. On the other hand, some immigrant printers had an enormous advantage in the credit and networks they had developed in Europe, and which they parlayed into commercial and political success once they landed in North America. -

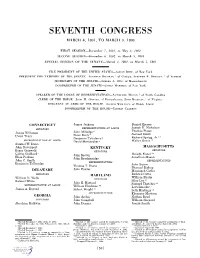

H. Doc. 108-222

SEVENTH CONGRESS MARCH 4, 1801, TO MARCH 3, 1803 FIRST SESSION—December 7, 1801, to May 3, 1802 SECOND SESSION—December 6, 1802, to March 3, 1803 SPECIAL SESSION OF THE SENATE—March 4, 1801, to March 5, 1801 VICE PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES—AARON BURR, of New York PRESIDENT PRO TEMPORE OF THE SENATE—ABRAHAM BALDWIN, 1 of Georgia; STEPHEN R. BRADLEY, 2 of Vermont SECRETARY OF THE SENATE—SAMUEL A. OTIS, of Massachusetts DOORKEEPER OF THE SENATE—JAMES MATHERS, of New York SPEAKER OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES—NATHANIEL MACON, 3 of North Carolina CLERK OF THE HOUSE—JOHN H. OSWALD, of Pennsylvania; JOHN BECKLEY, 4 of Virginia SERGEANT AT ARMS OF THE HOUSE—JOSEPH WHEATON, of Rhode Island DOORKEEPER OF THE HOUSE—THOMAS CLAXTON CONNECTICUT James Jackson Daniel Hiester Joseph H. Nicholson SENATORS REPRESENTATIVES AT LARGE Thomas Plater James Hillhouse John Milledge 6 Peter Early 7 Samuel Smith Uriah Tracy 12 Benjamin Taliaferro 8 Richard Sprigg, Jr. REPRESENTATIVES AT LARGE 13 David Meriwether 9 Walter Bowie Samuel W. Dana John Davenport KENTUCKY MASSACHUSETTS SENATORS Roger Griswold SENATORS 5 14 Calvin Goddard John Brown Dwight Foster Elias Perkins John Breckinridge Jonathan Mason John C. Smith REPRESENTATIVES REPRESENTATIVES Benjamin Tallmadge John Bacon Thomas T. Davis Phanuel Bishop John Fowler DELAWARE Manasseh Cutler SENATORS MARYLAND Richard Cutts William Eustis William H. Wells SENATORS Samuel White Silas Lee 15 John E. Howard Samuel Thatcher 16 REPRESENTATIVE AT LARGE William Hindman 10 Levi Lincoln 17 James A. Bayard Robert Wright 11 Seth Hastings 18 REPRESENTATIVES Ebenezer Mattoon GEORGIA John Archer Nathan Read SENATORS John Campbell William Shepard Abraham Baldwin John Dennis Josiah Smith 1 Elected December 7, 1801; April 17, 1802. -

Washington City, 1800-1830 Cynthia Diane Earman Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School Fall 11-12-1992 Boardinghouses, Parties and the Creation of a Political Society: Washington City, 1800-1830 Cynthia Diane Earman Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Earman, Cynthia Diane, "Boardinghouses, Parties and the Creation of a Political Society: Washington City, 1800-1830" (1992). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 8222. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/8222 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BOARDINGHOUSES, PARTIES AND THE CREATION OF A POLITICAL SOCIETY: WASHINGTON CITY, 1800-1830 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in The Department of History by Cynthia Diane Earman A.B., Goucher College, 1989 December 1992 MANUSCRIPT THESES Unpublished theses submitted for the Master's and Doctor's Degrees and deposited in the Louisiana State University Libraries are available for inspection. Use of any thesis is limited by the rights of the author. Bibliographical references may be noted, but passages may not be copied unless the author has given permission. Credit must be given in subsequent written or published work. A library which borrows this thesis for use by its clientele is expected to make sure that the borrower is aware of the above restrictions. -

Concealed Authorship on the Eve of the Revolution

CONCEALED AUTHORSHIP ON THE EVE OF THE REVOLUTION: PSEUDONYMITY AND THE AMERICAN PERIODICAL PUBLIC SPHERE, 1766-1776 A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School University of Missouri-Columbia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts By MICHAEL PATRICK MARDEN Dr. Jeffrey L. Pasley, Thesis Supervisor JULY 2009 Copyright by Michael Patrick Marden 2009 All Rights Reserved The undersigned, appointed by the Dean of the Graduate School, have examined the thesis entitled CONCEALED AUTHORSHIP ON THE EVE OF THE REVOLUTION: PSEUDONYMITY AND THE AMERICAN PERIODICAL PUBLIC SPHERE, 1766-1776 Presented by Michael Patrick Marden In candidacy for the degree of Master of Arts And hereby certify that, in their opinion, it is worthy of acceptance. Professor Jeffrey L. Pasley Professor Michelle Morris Professor Earnest L. Perry ACKNOWLEDMENTS I have already begun to incur many debts. First, I want to thank my parents Bill and Maggi Marden for their encouragement and unwavering love during this effort. My thanks go out to my sister, Elizabeth Mary Marden, whose good humor saw me through more than one trying moment. I want to thank the members of my committee, Dr. Jeffrey Pasley, to whose work and mind I am deeply indebted, and Dr.’s Michelle Morris and Earnest L. Perry. The feedback I received from you was indispensable. In addition, my thanks go out to the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation who are more than generous to keep their records online and free to the public. Further, the efforts of Readex to find and digitize newspaper ephemera in their Archive of Americana is absolutely brilliant and I happily count myself among the many scholars who have benefited from their efforts.