Varnum V. Brien at Ten Years

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Story of in Re Marriage Cases (2010), Available At

Santa Clara Law Santa Clara Law Digital Commons Faculty Publications Faculty Scholarship 6-1-2010 Six Cases in Search of a Decision: The tS ory of In re Marriage Cases Jean C. Love Santa Clara University School of Law, [email protected] Patricia A. Cain Santa Clara University School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.law.scu.edu/facpubs Part of the Law Commons Automated Citation Jean C. Love and Patricia A. Cain, Six Cases in Search of a Decision: The Story of In re Marriage Cases (2010), Available at: http://digitalcommons.law.scu.edu/facpubs/617 This Book Chapter is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Santa Clara Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Santa Clara Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Six Cases in Search of a Decision: The Story of In re Marriage Cases Patricia A. Cain and Jean C. Love ―Whatever is a reality today, whatever you touch and believe in and that seems real for you today, is going to be — like the reality of yesterday — an illusion tomorrow.‖1 On May 15, 2008, the Supreme Court of California handed down its decision in the much awaited litigation officially known as In re Marriage Cases.2 The case was actually a consolidation of six individual cases, all raising the same issue: Is denial of marriage to same-sex couples valid under the California Constitution? These six cases, as with Pirandello‘s six characters in search of an author, took center stage for a time, not in a real theater, but rather in the evolving drama over extending equal marriage rights to gay men and lesbians. -

Faces of the 2008 Annual Meeting See Classified Section for Details

37678_IL 8/4/08 10:31 PM Page 1 THE Volume 68 Number 8 August 2008 IOWAIOWA LAWYERLAWYER FacesFaces ofof thethe 20082008 AnnualAnnual MeetingMeeting ALSO IN THIS ISSUE – BOG authorizes disaster task force – Meet ISBA’s new vice president – Graves receives association’s top award – Foundation board approves grants 37678_IL 8/4/08 10:31 PM Page 2 David Baker (top photo) takes the oath of office as the 107th justice of the Iowa Supreme Court from Governor Chet Culver during his investiture ceremony on June 20. Observing in the background are Justice Brent Appel (left) and Justice David Wiggins. Justice Baker’s daughters, Elizabeth and Catherine, help their father don his robe (right photo) during the ceremony. Born in 1952 and raised in Waterloo, Justice Baker received his B.A. degree in Sociology from the University of Iowa in 1975 and his J.D. with high honors from U of I in 1979. He practiced law in Cedar Rapids from 1979 to January 2005 when he was appointed to the district court bench by Governor Tom Vilsack. He served as a district court judge for nearly two years until he was appointed to the Iowa Court of Appeals in November 2006. During his legal career, Justice Baker has served on numerous ISBA and Linn County Bar Association committees, including as a member of the board of governors for the ISBA. Correction A photo caption on page 14 of the July 2008 Iowa Lawyer under-reported the severity of the Cedar Rapids flood. The caption said the Cedar River crested eight feet above flood stage. -

ALLIES Is Allowed One Vote

CREDIT UNION FACTS: safe. sound. local. Save You Money Owned by Members Credit unions are not-for-profit financial institutions. Every credit union member is an owner of the financial Meaning they offer many of the same products and cooperative, not just a customer. All credit union services as banks—including savings and checking members are owners and elect a volunteer board of accounts, loans, ATMs and online banking—but directors to represent their interests. there areIOWA’S also big differences that CREDIT can save you money. UNION Credit unions are owned and controlled by their Volunteer Board of Directors members, not profit-driven shareholders. That means the average credit union can offer better rates and The credit union’s board of directors is elected by the lower fees. membership and from the membership. Each member ALLIES is allowed one vote. Board members are volunteers and are not compensated for their efforts. Safe & Sound AT THE STATE AND FEDERALHow to Join LEVEL Every Iowa credit union carries federal deposit insurance through the National Credit Union Share To become a credit union member, you must have a Insurance Fund (NCUSIF), administered by the “common bond” with a certain employment group, National Credit Union Administration (NCUA). association membership or a well-defined geographical The NCUA is like what the FDIC is to banks. region. Visit www.FindACreditUnion.com to locate This insurance protects members’ accounts up to credit unions near you that you’re eligible to join! $250,000. Local Credit unions are good corporate citizens and are located within the communities they serve. -

Preservationism, Or the Elephant in the Room: How Opponents of Same-Sex Marriage Deceive Us Into Establishing Religion

19_WILSON.DOC 2/8/2007 2:11 PM PRESERVATIONISM, OR THE ELEPHANT IN THE ROOM: HOW OPPONENTS OF SAME-SEX MARRIAGE DECEIVE US INTO ESTABLISHING RELIGION JUSTIN T. WILSON* “People place their hand on the Bible and swear to uphold the Constitution. They don’t put their hand on the Constitution and swear to uphold the Bible.” –Jamin Raskin, Professor of Law, American University, in testimony before the Maryland Senate Judicial Proceedings Committee1 INTRODUCTION...............................................................................................................562 I. DEFINING “MARRIAGE”........................................................................................567 A. A Brief History and Overview................................................................567 B. The Establishment Clause and Our Religious Heritage......................576 II. A PRIMER ON THE FEDERAL MARRIAGE AMENDMENT AND ITS KIN..................586 A. What Are Same-Sex Marriage Bans and What Do They Do? .............586 B. Who Supports the FMA? .........................................................................592 III. WHERE ARE WE GOING, AND WHY ARE WE IN THIS HANDBASKET?: A SHIFT IN FUNDAMENTAL(IST) RHETORIC .............................................................597 A. The Theoretical Underpinnings of Preservationism............................599 B. Preservationism: An Application ...........................................................602 IV. MODERN ESTABLISHMENT CLAUSE JURISPRUDENCE: “HOPELESS DISARRAY” ............................................................................................................604 -

Independent Expenditures for Or Against State Candidates Or Ballot Issues in Iowa

Independent Expenditures For or Against State Candidates or Ballot Issues in Iowa Organization Name Organization City Organization State Organization Zip Iowa Association for Justice West Des Moines IA 50266 Iowa Citizens for Community Des Moines IA 50311 Improvement Action Fund National Association of REALTORS CHICAGO IL 60611 Fund Taxpayers Protection Alliance Washington DC 20005 National Association of REALTORS CHICAGO IL 60611 Fund Working America Washington DC 20006 Working America Washington DC 20006 Working America Washington DC 20006 Americans For Prosperity Arlington VA 22201 Americans For Prosperity Arlington VA 22201 Americans For Prosperity Arlington VA 22201 AFA Action, Inc. West Des Moines IA 50266 AFA Action, Inc. West Des Moines IA 50266 Page 1 of 2324 09/29/2021 Independent Expenditures For or Against State Candidates or Ballot Issues in Iowa Organization Email Contact First Name Contact Last Name Contact Email [email protected] Andrew Mertens [email protected] Matthew Covington [email protected] MARC GALL [email protected] David Williams [email protected] MARC GALL [email protected] Krissi Jimroglou [email protected] Krissi Jimroglou [email protected] Krissi Jimroglou [email protected] Alex Varban [email protected] Alex Varban [email protected] Alex Varban [email protected] Bob Vander Plaats [email protected] [email protected] Bob Vander Plaats [email protected] Page 2 of 2324 09/29/2021 Independent Expenditures For or Against State Candidates -

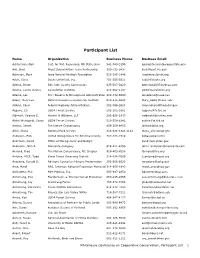

Participant List

Participant List Name Organization Business Phone Business Email Achterman, Gail Inst. for Nat. Resources, OR State Univ. 541-740-3190 [email protected] Ack, Brad Puget Sound Action Team Partnership 360-725-5437 [email protected] Ackelson, Mark Iowa Natural Heritage Foundation 515-288-1846 [email protected] Adair, Steve Ducks Unlimited, Inc. 701-355-3511 [email protected] Adams, Bruce San Juan County Commission 435-587-2820 [email protected] Adams, Laurie Davies Coevolution Institute 415-362-1137 [email protected] Adams, Les Ntn’l Oceanic & Atmospheric Administration 202-482-6090 [email protected] Addor, Mary Lou Natural Resources Leadership Institute 919-515-9602 [email protected] Adkins, Carol Federal Highway Administration 202-366-2024 [email protected] Agpaoa, Liz USDA Forest Service 202-205-1661 [email protected] Albrecht, Virginia S. Hunton & Williams, LLP 202-955-1943 [email protected] Alden Weingardt, Susan USDA Forest Service 510-559-6342 [email protected] Aldrich, James The Nature Conservancy 859-259-9655 [email protected] Allen, Diana National Park Service 314-436-1324 x112 [email protected] Anderson, Bob United Winegrowers for Sonoma County 707-433-7319 [email protected] Anderson, David Office of Management and Budget [email protected] Anderson, John R. Monsanto Company 919-821-9295 [email protected] Annand, Fred The Nature Conservancy, NC Chapter 919-403-8558 [email protected] Antoine, AICP, Todd Great Rivers Greenway District 314-436-7009 [email protected] Anzalone, Ronald D. Advisory Council on Historic Preservation 202-606-8523 [email protected] Arce, Mardi NPS, Jefferson National Expansion Memorial 314-655-1643 [email protected] Archuletta, Phil P&M Plastics, Inc. -

![Spring / Summer 2018 Newsletter [PDF]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0688/spring-summer-2018-newsletter-pdf-1190688.webp)

Spring / Summer 2018 Newsletter [PDF]

California Supreme Court Historical Society newsletter · spring/ summer 2018 THE MARRIAGE CASES AN INSIDER’S PERSPECTIVE TEN YEARS LATER The Story of In re Marriage Cases: Our Supreme Court’s Role in Establishing Marriage Equality in California By Justice Therese M. Stewart* Therese M. Stewart, then of the Office of the San Francisco City Attorney, prepares to speak at a press conference after arguing in support of marriage equality before the California Supreme Court on Tuesday, May 25, 2004. AP Photo / Jeff Chiu t a few minutes before 10:00 a.m. on Thursday, traffic we knew it was receiving. After what felt like an May 15, 2008, attorneys who had worked for eternity, we heard a sound in the distance that seemed ASan Francisco litigating In re Marriage Cases1 like cheering. We wondered whether the anti-marriage were assembled in my City Hall office. We trolled the equality forces waiting at the courthouse had the num- California Supreme Court’s website as we waited for the bers to make such a sound carry all the way across the decision we’d been promised would be forthcoming, plaza. We were confident the pro-marriage forces did. in a notice posted by the Court the day before. Some Still, we wanted a firmer answer than that. We couldn’t were optimistic, others apprehensive. I felt butterflies immediately access the opinion online and the waiting below my ribcage, nearer to my heart than my stom- became almost unbearable. Finally, the phone rang, and ach. Dennis Herrera, my boss and the San Francisco I answered it. -

Letter from Iowa: Same-Sex Marriage and the Ouster of Three Justices

PETTYS FINAL 5/14/2011 12:44:21 PM Letter from Iowa: Same-Sex Marriage and the Ouster of Three Justices Todd E. Pettys∗ I. INTRODUCTION On November 2, 2010, voters in Iowa fired three of the Iowa Supreme Court’s seven justices.1 Under constitutional reforms that Iowans had adopted nearly half a century earlier, each of those justices had been appointed by the state’s governor from a list of names supplied by the state’s judicial nominating commission,2 but then was required to stand for a retention vote after a short initial period of service and every eight years thereafter.3 Chief Justice Marsha Ternus had been appointed to the state’s high court by Republican Governor Terry Branstad in 1993 and was on the November 2010 ballot seeking her third eight-year term; Justice Michael Streit had been appointed by Democratic Governor Tom Vilsack in 2001 and was seeking his second eight-year term; and Justice David Baker had been appointed by Democratic Governor Chet Culver in 2008 and was seeking his first eight-year term.4 Under ordinary circumstances, each of those justices would have been virtually guaranteed success on Election Day. Since Iowa moved from an ∗ H. Blair and Joan V. White Professor of Law, University of Iowa College of Law. I wish to thank Justice Randy Holland, Steve McAllister, and the editors of the Kansas Law Review for inviting me to participate in this symposium; Michelle Falkoff, Linda McGuire, Caroline Sheerin, and John Whiston for their helpful comments on earlier drafts; and Karen Anderson for her helpful comments and research assistance. -

U.S. Supreme Court Holds First Amendment Shields Westboro Baptist Military Funeral Protesters from Tort Liability

LESBIAN/GAY LAW NOTES April 2011 49 U.S. SUPREME COURT HOLDS FIRST AMENDMENT SHIELDS WESTBORO BAPTIST MILITARY FUNERAL PROTESTERS FROM TORT LIABILITY A majority of the Supreme Court of the dismissed Snyder’s claims for defama- public matters was intended to mask an at- United States has held that members of tion and publicity given to private life, and tack on Snyder over a private matter.” Rob- the Westboro Baptist Church, who regu- held a trial on the remaining claims. A jury erts held that Westboro’s message “cannot larly protest military funerals holding found for Snyder on the remaining claims be restricted simply because it is upsetting signs bearing slogans expressing their dis- and held Westboro liable for $2.0 million or arouses contempt” and concluded that approval of America’s tolerance of homo- in compensatory damages and $8.0 mil- the jury verdict imposing tort liability on sexuality, such as “God Hates Fags,” “Fag lion in punitive damages; the trial court Westboro for intentional infliction of emo- Troops,” “Thank God for Dead Soldiers,” later remitted the punitive damages award tional distress must be set aside. and “America is Doomed,” was shielded by to $2.1 million. Westboro appealed to the Justice Roberts also rejected Snyder’s ar- the First Amendment from tort liability for 4th Circuit Court of Appeals, which held gument that he was “a member of a captive causing extreme emotional distress to the that Westboro was entirely shielded from audience at his son’s funeral,” stating that father of an Iraq war veteran when they liability by the First Amendment. -

Contextualizing Varnum V. Brien: a "Moment" in History Patricia A

Santa Clara Law Santa Clara Law Digital Commons Faculty Publications Faculty Scholarship 1-1-2009 Contextualizing Varnum v. Brien: A "Moment" in History Patricia A. Cain Santa Clara University School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.law.scu.edu/facpubs Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation 13 J. Gender Race & Just. 27 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Santa Clara Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Santa Clara Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Contextualizing Varnum v. Brien: A "Moment" in History PatriciaA. Cain * I. INTRODUCTION Varnum v. Brien' is the last case in a line of state constitutional law challenges in what has been a a fifteen-year campaign by LGBT 2 public interest lawyers seeking legal recognition for same-sex couples. While the litigation may be over for now,3 the larger battle is just beginning. The Iowa Supreme Court's ruling in Varnum will play a central role in this future battle. It stands as part of a major "moment" in the modem history of recognizing equal marriage rights for same-sex couples. By "moment," I do not mean a single point in time, but a prolonged period of a year or so over which a substantial shift occurs. I see three key moments in this modem battle for marriage equality. The first distinct moment is the period of time in 1996 surrounding the Hawaii litigation4 and the incipient backlash evidenced by the enactment of various "Defense of Marriage" laws, both at the federal and state level. -

Bob Vander Plaats and Chuck Hurley Endorse

Fred Karger 3699 Wilshire Blvd., Suite 1290 O- Los Angeles> CA 90010 j > r' < c \ June 13, 2013 Office of the General Counsel _ , ^ ^ Federal Election Commission ^ f ^ 999 E Street, N:W. MUR # f OJ Washington, DC 20463 I want to bring to your attention possible violations of the Federal Election Campaign Act by former United States Senator Rick Santorum, the National Organization for Marriage and Mr. Bob V/ander Plaats. I respectfully ask the Federal Election Commission to conduct a full investigation into the likelihood that the National Organization for Marriage, its officers and major supporters paid the Family Leader and its president Mr. Bob Vander Plaats up to $1 million to secure its ' endorsement of then presidential candidate Rick Santorum. Mr. Vander Plaats' endorsement ? of Mr. Santorum occurred just two weeks before the Iowa Caucus and enabled Mr. Santorum to , beat former Governor Mitt Rornney in the first contest of the 2012 Presidential Campaign. i Additionally, it appears that there was coordination between the Santorum for President Campaign, Mr. Brian Brown, President of the National Organization for Marriage and Mr. Bob Vander Plaats, President of the Family Leader for the purpose of funding the Vander Plaats created Super PAC, Families for Leaders. The Familiesfor Leaders Super PAC was established to , support Mr. Santorum in Iowa. | I Complainant and Respondents Complainant: Fred Karger 3699 Wilshire Blvd., Suite 1290 Los Angeles, CA 90010 Respondents: Siehator Rick Santorum P.O. Box 37 Verona, PA 15147 National Organization for Marriage, Inc. Mr. Brian Brown, President 2029 K Street, NW Suite 300 Washington, DC 20006 Mr. -

Memorial Resolution Published in Senate

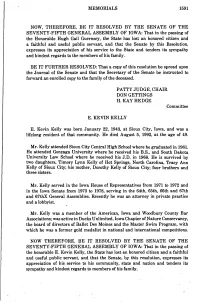

MEMORIALS 1591 NOW, THEREFORE, BE IT RESOLVED BY THE SENATE OF THE SEVENTY-FIFTH GENERAL ASSEMBLY OF IOWA: That in the passing of the Honorable Hugh Gail Guernsey, the State has lost an honored citizen and a faithful and useful public servant, and that the Senate by this Resolution, expresses its appreciation of his service to the State and tenders its sympathy and kindest regards to the members of his family. BE IT FURTHER RESOLVED: That a copy of this resolution be spread upon the Journal of the Senate and that the Secretary of the Senate be instructed to forward an enrolled copy to the family of the deceased. PATTY JUDGE, CHAIR DON GETTINGS H. KAY HEDGE Committee E. KEVIN KELLY E. Kevin Kelly was born January 22, 1943, at Sioux City, Iowa, and was a lifelong resident of that community. He died August 5, 1992, at the age of 49. Mr. Kelly attended Sioux City Central High School where he graduated in 1961. He attended Gonzaga University where he received his B.S., and South Dakota University Law School where he received his J.D. in 1968. He is survived by two daughters, Timory Lynn Kelly of Hot Springs, North Carolina, Tracy Ann Kelly of Sioux City; his mother, Dorothy Kelly of Sioux City; four brothers and three sisters. Mr. Kelly served in the Iowa House of Representatives from 1971 to 1972 and in the Iowa Senate from 1973 to 1978, serving in the 64th, 65th, 66th and 67th and 67thX General Assemblies. Recently he was an attorney in private practice and a lobbyist.